Chaozhou Tea Rice: the Art in a Cup of Tea

2023-04-21LiHonggu

Li Honggu

Did the Tang and Song Dynasties have different tea-drinking methods? Why is Matcha popular in Japan, while China prefers brewing tea? What stories of commoners lives are hidden in the age-old tea houses of Bashu? This book delves deeply into Chinese tea from historical, utensil, cultural, and lifestyle perspectives, guiding readers through the essence of Chinese tea culture.

In Chaozhou dialect, tea leaves are called “tea rice,” signifying their importance, akin to rice. Its unthinkable to go a day without tea. If every family brews tea twice daily (approx. 0.88 ounces), a Chaozhou household consumes 0.75 kg of tea per month, amounting to 9 kg annually. Considering consumption at shops, restaurants, tea houses, factories, and offices, Chaozhou boasts the highest tea consumption in the country.

Immersed in Gongfu Tea

“Lets talk after this cup.” After a series of deliberate motions, Ye Hanzhong made a gesture to invite. The small blue-and-white tea cup emitted a warm steam with a faint floral aroma. The first sip tasted slightly bitter, but a delightful aftertaste emerged as it lingered. Smelling the base of the cup revealed a rich, fruity aroma that lingered for a long time. He then exhaled with satisfaction, noting that it was “Night-Blooming Jasmine,” a locally renowned “Phoenix Dancong” aroma.

He added that smelling the base of the cup helps judge the quality of the tea. In Ye Hanzhongs view, modern Wuyi Rock Tea feels “thin.” However, the local Phoenix Dancong, grown in higher altitudes, tastes slightly bitter at first but has a robust aftertaste, which he describes as “mountain essence.” High-altitude conditions increase the amino acid content in the tea leaves, and the taste resembles moss from foggy regions, strong, dominant, and lingering.

Chaozhou locals conduct all their conversations over tea. Amid the steaming cups, even tense situations mellow and cold atmospheres warm. Ye Hanzhongs guest room in an old arcade-style building on Ancient Arch Street epitomizes this. He is an inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage “Chaozhou Gongfu Tea” and brews tea with a relaxed attitude, not strictly adhering to formalities.

Ye Hanzhong says he began engaging with tea in 1986, working in tea procurement, storage, and trade. His true introduction to the art of tea was quite accidental during training with a master from the Daoquan school. This master, a once-wealthy man who had fallen on hard times, was deeply ingrained with the art of Gongfu tea. In his free time, he taught them how to brew tea. After enrolling in a postgraduate course in Tea Biochemistry at Zhejiang University in 1998, Ye delved deeper into the intricacies of Gongfu tea, realizing the purpose of every utensil and the logic behind each detail.

Yu Jiao of the Qing Dynasty summarized the essence of Gongfu tea in Chaojia Fengyueji -- Gongfu Tea, attributing it to the tea brewers character, mastery of tea art, and the leisure time for brewing good tea -- the three hallmarks of Gongfu tea.

Choosing the right tea is the first step. The “Night-Blooming Jasmine” that Ye Hanzhong served us that evening had been stored for about a year, the perfect age to bring out its charm. Many seasoned tea enthusiasts prefer tea aged for a year. At first glance, its color appears redder and richer, its aroma less pronounced, but the “throat feel” is exceptional.

The source of water is crucial. As Ye Hanzhong mentioned, ever since the Classic of Tea, the standard for choosing water has remained unchanged: “Mountain water is top-tier, river water is mid-tier, and well water is the last choice.” However, obtaining mountain water isnt realistic nowadays. He uses tap water for brewing, but first, he places it in a large vat to “condition” it. He adds a few broken mountain stones, sand from the Han River, or crystal sand purchased from a pet and plant market, creating a natural “soft water machine.” This process activates the water, ensuring the water used is “living water.”

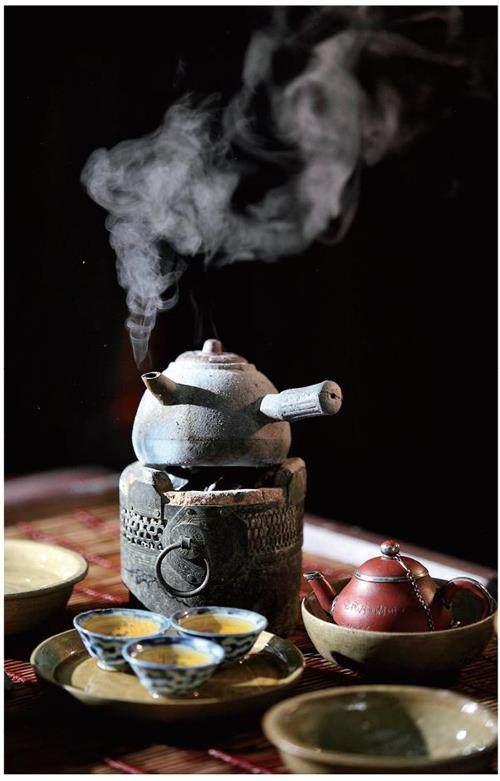

Then, “living water must be boiled with a living fire.” He adds lychee charcoal to a clay stove commonly known as a “wind stove.” The stove stands about six to seven inches tall with a flat top cover and a door with its own cover. Once the tea ceremony is finished, both covers are closed, allowing the loose charcoal inside to extinguish itself. The remaining embers can be used to light the next fire. Atop the red clay stove sits a sandy kettle, elegantly referred to as the “Jade Script Kettle.” Among the common folk, it is affectionately known as a “little teapot.” This kettle is crafted from “sandy clay.” The sandy kettle and the stove are complementary, collectively termed the “wind stove and thin pot.” When boiling water, he adds a few pieces of olive charcoal made from the kernel of a local variety called “black olive.” Due to the kernels density, this charcoal burns steadily and emits a unique fragrance not found in other types of wood charcoal. Using bronze tongs to handle the charcoal and a goose-feather fan to stoke the fire, watching the sparks fly, one is reminded of the old saying, “Bamboo stove, olive charcoal, personally brewed.”

Ye Hanzhong says that, if strictly following tradition, there should be a seven-step distance between the tea stove and the tea table. The tea attendant would boil the water in the courtyard and bring it to the front hall just in time for brewing. This seven-step distance is to ensure optimal timing, allowing the smoky aroma to dissipate and the boiling water to cool from its third boil to its second. At this point, experience takes over. When you hear the sound of rolling waves inside the sandy kettle and see steam spouting out, it indicates the water has just passed its second boil and hasnt reached the third. This is the ideal temperature for brewing tea.

He says this whole “bamboo stove, olive charcoal, personally brewed” method isnt just for nostalgia, as “water through sand becomes sweet; through stone, it becomes pleasant.” To prove this, he presented two white porcelain cups. One filled with water boiled using different methods indeed tasted different. The one with a harder and astringent taste was boiled using an electric kettle, while the softer and sweeter one was boiled with the “wind stove and thin pot.”

The tea setting before us is uncomplicated: a tea tray holds a teapot and three cups, flanked by three tea rinse containers resembling those from the Qing Dynasty, called “one primary, two secondaries.” The “primary rinse” is used for the tea cups, while the “secondary rinses” are for the teapot and for discarding wastewater. Ye Hanzhong mentions this is the original setup for Gongfu tea. When Gongfu tea was introduced to Chaozhou during the mid-Qing Dynasty, the saying was, “The tea must be from Wuyi, the pot from Mengchen, and the cup from Ruoshen,” where Mengchen and Ruoshen are the names of renowned craftsmen of the time, and their designs became highly sought after.

After the purple clay pot arrived in Chaozhou, local craftsmanship evolved, leading to the creation of hand-shaped red clay pots. The pot in Ye Hanzhongs hands is from the reputable “Yuan Xing Bing Ji.” Its more delicate than the purple clay pot and is better suited for Gongfu tea as it maintains the “ideal ratio of tea to water.” This red clay pot, after years of use, has developed a patina from tea residues. The spout, handle, and lid have been reinforced with silver edges. He finds it comfortable to use and believes in repairing and continuing its use if possible.

Its no big deal, he says. He even has a purple clay pot from the Qianlong era. The body is from Yixing, while the lid is from Chaozhou. The pot is densely studded with nails — he counted 113 in total. Nowadays, such craftsmanship is hard to come by. The three cups date back to the Republic of China era, made of blue and white porcelain. Theyre wide-mouthed, as small as a walnut, and the bottom reads “Ruoshens Collection.” Upon close inspection, theres a carved “錫 (xi)” character in the center of the cup. He explains that during festivals and ceremonies where tea is served to deities and ancestors, members of extended families would carve their names into their cups for identification.

Chaozhou people have an age-old tradition: “Three cups for tea, four for alcohol, two for outings.” Whether hiking or enjoying nature, twos company; four is the magic number for drinking, and when it comes to tea, regardless of how many participants, there are always three cups on the tea table. Ye Hanzhong explains that when the three cups are arranged together, they form the Chinese character “品 (pin),” symbolizing “virtue” or “character.” As the water is about to boil, Ye Hanzhong takes a sheet of white cotton paper and places some “Night-Blooming Jasmine” tea on it. He holds the papers edges and sways it above the charcoal fire, toasting it until the aroma fills the room. He then turns the tea leaves over for another round of toasting until the scent is pure and correct.

He states that aged tea should always undergo this “roasting” process. As the water begins to boil, he uses the sand spatula to pour water over the pot and cups, discards the wastewater, and starts the “tea introduction” process, pouring the tea leaves into the teapot. Ye Hanzhong says that the skill involved in tea loading is crucial, as it affects the quality of the tea soup, including aspects such as whether the tea pours smoothly and whether the amount of tea soup is just right. Some people use a tea-infusing pot to brew their tea, and after just one or two infusions, the tea leaves inside the pot have swollen up to the point where they push the lid open. Alternatively, when pouring the tea into a cup, the cup might be full of tea dust. These are all consequences of the improper “tea introduction” process. First, he places the coarsest tea leaves at the bottom of the pot, near the spout. Then, he packs the middle layer with finer tea dust. Finally, he sprinkles a slightly coarser layer of tea leaves on top, ensuring that every tea leaf on the paper is stuffed into the tea-infusing pot, which is as small as a babys fist.

Ye Hanzhong explains that every tea brewing movement is meaningful; while the various tea tray tools might seem complicated, not a single one is merely for show.They are all practical utensils. After all, Gongfu tea is not something to be placed on a pedestal; it is a part of the daily life of the people in Chaozhou. The so-called “Gongfu” is quite simple; it is all about how to brew the best cup of tea soup.

The Way of Tea:

The Freedom of Chinese Tea

Li Honggu

Tiandi Press

June 2021

98.00 (CNY)

Li Honggu

Li Honggu is the editor-in-chief of Sanlian Life Weekly, and the author of The Disempowered and The Beginning of the China Nation.