Disordered eating behaviour and eating disorder among adolescents with type 1 diabetes: An integrative review

2022-11-29MariaConceiSantosOliveiraCunhaFranciscoClcioSilvaDutraLauraMartinsMendesCavaleiroBritoRejaneFerreiraCostaMariaWendianeGueirosGasparDaniloFerreiraSousarcioFlvioMouradeArajoMariaVeraciOliveiraQueiroz

Maria Conceição Santos Oliveira Cunha,Francisco Clécio Silva Dutra,Laura Martins Mendes Cavaleiro Brito,Rejane Ferreira Costa,Maria Wendiane Gueiros Gaspar,Danilo Ferreira Sousa,Márcio Flávio Moura de Araújo,Maria Veraci Oliveira Queiroz

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Type 1 diabetes (DT1) in adolescents brings behavioural changes,altered nutritional habits,and eating disorders.

AIM

To identify and analyze the validated instruments that examine the disordered eating behaviour and eating disorders among adolescents with DT1.

METHODS

An integrative review was accomplished based on the following databases:PubMed,LILACS,CINAHL,Scopus,Web of Science,and Reference Citation Analysis (RCA),including publications in Portuguese,English,or Spanish,without time limit and time published.

RESULTS

The main instruments to evaluate disordered eating behaviour were The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised,The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey,and the eating attitudes test-26,and for eating disorders the main instruments used were The Bulimic Investigation Test of Edinburgh,The Binge Eating Scale,The Child Eating Disorder Examination,The five questions of the (Sick,Control,One,Fat and Food),and The Mind Youth Questionnaire.These instruments showed an effect in evaluating risks regarding nutritional habits or feeding grievances,with outcomes related to weight control,inadequate use of insulin,and glycaemia unmanageability. We did not identify publication bias.

CONCLUSION

Around the world,the most used scale to study the risk of disordered eating behaviour or eating disorder is The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised. International researchers use this scale to identify high scores in adolescents with DT1 and a relationship with poorer glycemic control and psychological problems related to body image.

Key Words: Adolescent; Type 1 diabetes mellitus; Validation studies; Nutritional behaviour; Eating disorder;Review

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes (DT1) in adolescents brings behavioural changes,highlighting altered nutritional habits and eating disorders (ED). It is worth emphasizing that the greatest challenge of diabetes treatment is glycaemic control through insulin therapy,good nutritional habits,and regular physical activity[1],in addition to other health behaviours. However,studies about behaviours with DT1 showed a higher risk of developing ED and dissatisfaction with their body image than their pairs without diabetes[2,3].

The disordered eating behaviour (DEB) is related to active behaviouring on a diet or to feast,compulsive eating,or purging (inefficient use of laxatives,diuretics,and self-induced vomit) and its frequency has become considerably higher in the last years at different parts of the world[4,5].

The prevalence of DEBs among adolescents is estimated at 10% in Western cultures[6]. In Israel,the estimates are 8.2% among female adolescents and 2.8% for male adolescents[7]. DEB and ED were already associated with diabetes mellitus (DM)[8,9].

ED encompass a group of psychiatric conditions that may lead to a persistent failure in attending to nutritional and metabolic needs,thus resulting in severe psychosocial impairment[10]. EDs are most prevalent among individuals with DM1 than in the average population[11].

EDs are eating disorder habits with central psychopathology related to eating,food concerns,and body image. There are four main types of ED: Anorexia nervosa,bulimia nervosa,periodic compulsive eating disorder,and specified eating or ED[12].

The knowledge of validated instruments that examined DEB and ED of adolescents with DT1 may subsidize prevention actions for potential risks to altered eating habits and the handling of grievances related to these disorders,thus supporting the decision in nursing clinical practice and other professionals that give care to adolescents with DT1. Therefore,the purpose of this study was to identify and analyze validated instruments that examined disordered eating behaviour and ED among adolescents with DT1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is an integrative review of the literature conducted from February to April 2021 on a single desktop machine. The PICO strategy,which represents the acronym Patient,Intervention,Comparison,and Outcomes,was used to construct the guiding question of the research. The categories of this strategy are respectively fulfilled by: “Adolescents with type 1 diabetes mellitus”; “validation studies”; and “eating disorders” and “disordered eating behaviour”. Therefore,the following question was made: What validated instruments examined the DEB or ED of adolescents with DT1?

The article selection was based on titles and abstracts of the quoted articles,with the selection of the studies’ inclusion and exclusion conditions,without establishing a temporal cut for the inclusion of studies. The inclusion conditions were as follows: Fully available articles in the electronic networks;national and international periodicals; studies regarding validated tools about disordered behaviour or eating disorder of adolescents with DT1; written in Portuguese,Spanish,or English. In contrast,the exclusion conditions were: Incomplete or incompatible texts about the subject,case reports,book chapters,monographs,review studies,editorials,stories in newspapers,or any non-scientific text.

The search for articles was done in the following databases: PubMed/Medline,LILACS,Cinahl,Scopus,Reference Citation Analysis (RCA),and Web of Science. The Periodical Portal,CAFe,from the Coordination for Improving Higher Education Personnel (CAPES),was used to access these five databases. The following Health Science Descriptors (DeCS) and (MeSH) were used: “Adolescente”,“diabetes mellitus tipo 1”,and “Transtornos da Alimentação e da Ingestão de Alimentos”,and their respective English versions are “Adolescent”,“type 1 diabetes mellitus”,and “disorders from eating and food intake”. The crossings were made using the Boolean operator “AND” to combine the descriptors: Adolescent” AND “diabetes mellitus type 1” AND “feeding and eating disorders”.

The descriptors were delimited for each selected database (Medical Subject Headings – MeSH,Health Science Descriptors – DeCS,and CINAHL Headings – MH). There was no publication year threshold.The study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)recommendations[13].

The evidence level classification regarding the guiding question concerning studies of Intervention/Treatment or Diagnosis/Diagnostic test[14] was added and presented the following seven levels: (1)Evidence of a systematic review or a meta-analysis of all relevant randomized controlled studies; (2)evidence obtained from well-made randomized controlled studies; (3) evidence obtained from adequately designed controlled studies without randomization; (4) evidence of well-designed casecontrol and cohort studies; (5) evidence of systematic reviews from descriptive and qualitative studies;(6) evidence of unique descriptive or qualitative studies; and (7) evidence from authorities opinions or reports from a committee of experts.

Random effects meta-analysis of proportions was perform using the 'meta' package in R 4.0.

RESULTS

An initial search for the literature that composed the integrative review obtained a result of 728 studies,distributed in 258 articles published in PubMed/MedLine,6 in Lilacs,100 in Cinahl,207 in Scopus,and 157 in Web of Science. After the application of the inclusion and exclusion conditions,the final sample was composed of 13 studies in the following databases: LILACS (1); PubMed/MedLine (4); Cinahl (2);Scopus (3); and Web of Science (3).

The stages of search and selection of studies for the review are summarized in Figure 1,which was made according to the PRISMA[13].

Figure 1 Flowchart of study selection process adapted from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses.

Thirteen studies from nine different English and non-English countries were found; two each were conducted in Norway,Italy,Canada,and Turkey. The others were published in the following countries:Brazil,United States,Germany,Netherlands,and China,each with one study. There was an intense time variation regarding the publication year,where only one study was published annually and,exceptionally,two studies in a few years. The first study was published in 2010,and the most recent in 2021. Two studies each were conducted in 2013 and 2018 and three in 2017. The other years had one study as per Table 1.

Table 1 Characterisation of primary studies,according to author(s),year,title,objective,instruments,conclusion,and evidence level(Fortaleza,Ceará,Brazil,2021)

a l[1 9],2 0 1 3 N o r m s,a n d F a c t o r S t r u c t u r e o f t h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y R e v i s e d i n a L a r g e S a m p l e o f C h i l d r e n a n d A d o l e s c e n t s w i t h T y p e 1 D i a b e t e s p r o p e r t i e s o f t h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y –R e v i s e d (D E P S-R) i n a l a r g e s a m p l e o f y o u n g p a t i e n t s w i t h D T 1 t o e s t a b l i s h r u l e s a n d v a l i d a t e i t a g a i n s t t h e E a t i n g A t t i t u d e s T e s t 1 2(E A T-1 2)S u r v e y–R e v i s e d (D E P S-R)t o o l f o r D E B i n p e o p l e w i t h D T 1,w h i c h i s r e l e v a n t i n p r a c t i c a l c l i n i c s. T h e d i s c o v e r i e s s u p p o r t t h i s i m p o r t a n t s c r e e n i n g t o o l's u t i l i t y i n i d e n t i f y i n g e a t i n g d i s o r d e r s a m o n g y o u n g p a t i e n t s w i t h t y p e 1 d i a b e t e s M a r k o w i t z e t a l[2 5],2 0 1 0 B r i e f S c r e e n i n g T o o l f o r D i s o r d e r e d E a t i n g i n D i a b e t e s T o u p d a t e a n d v a l i d a t e a s p e c i f i c d i a b e t e s t r a c k i n g t o o l f o r e a t i n g d i s o r d e r s (D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y D E P S) i n y o u n g o n e s w i t h t y p e 1 d i a b e t e s.T h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m-S u r v e y-R e v i s e d (D E P S-R)F u t u r e s t u d i e s m u s t f o c u s o n u s i n g D E P S-R t o i d e n t i f y h i g h-r i s k p o p u l a t i o n s f o r t h e p r e v e n t i o n a n d e a r l y i n t e r v e n t i o n o f d i s o r d e r e d e a t i n g b e h a v i o u r s L e v e l V I P i n n a e t a l[2 6],2 0 1 7 A s s e s s m e n t o f e a t i n g d i s o r d e r s w i t h t h e d i a b e t e s e a t i n g p r o b l e m s s u r v e y r e v i s e d (D E P S-R)i n a r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s a m p l e o f i n s u l i n-t r e a t e d d i a b e t i c p a t i e n t s: a v a l i d a t i o n s t u d y i n I t a l y T o e v a l u a t e p a t i e n t s w i t h t y p e 1 a n d t y p e 2 d i a b e t e s t r e a t e d w i t h i n s u l i n a n d t h e p s y c h o m e t r i c c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s o f t h e I t a l i a n v e r s i o n o f t h e D E P S-R s c a l e T h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y-R e v i s e d (D E P S-R)A d u l t s a n d a d o l e s c e n t s w i t h t y p e 1 a n d t y p e 2 d i a b e t e s t r e a t e d w i t h i n s u l i n p a r t i c i p a t e d i n t h e s t u d y.T h e I t a l i a n v e r s i o n o f t h e D E P S-R s c a l e s h o w e d a g o o d c o n s t r u c t v a l i d i t y,i n t e r n a l c o n s i s t e n c y,a n d a n e x c e l l e n t r e a s o n a b l e d e g r e e o f r e p r o d u c i b i l i t y i n t h i s p u b l i c L e v e l V I L v e t a l[1 8],2 0 2 1 I n s t r u m e n t C o n t e x t R e l e v a n c e E v a l u a t i o n,T r a n s l a t i o n,a n d P s y c h o-m e t r i c T e s t i n g o f t h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y-R e v i s e d (D E P S-R)a m o n g P e o p l e w i t h T y p e 1 D i a b e t e s i n C h i n a T o a d a p t t h e D E P S-R f o r M a n d a r i n a n d t e s t i t s p s y c h o m e t r i c p r o p e r t i e s a m o n g a d o l e s c e n t s a n d a d u l t s w i t h t y p e 1 d i a b e t e s i n C h i n a T h e D i a b e t e s E a t i n g P r o b l e m S u r v e y-R e v i s e d (D E P S-R)T h e C h i n e s e v e r s i o n o f t h e D E P S-R d e s c r i b e d a h i g h p r o p o r t i o n o f d i s o r d e r e d e a t i n g b e h a v i o u r a m o n g a d o l e s c e n t s a n d a d u l t s w i t h D T 1,t h u s i n d i c a t i n g a n e e d f o r s p e c i a l a t t e n t i o n b y h e a l t h p r o f e s s i o n a l s a n d r e s e a r c h e r s i n C h i n a L e v e l I I I

Concerning the evidence level,based on the methodological analysis of the studies,nine are descriptive studies with a quantitative approach,and four are experimental studies of the clinical trial type. Among the observational studies,nine are descriptive with a quantitative approach.

All studies varied in the evidence level among II,III,IV,and VI. Two clinical trials[15,16] were classified as level II. A clinical trial without randomization and a quasi-experimental study[17,18] were classified as level III. A cohort study[19] was classified as level IV. The other studies[8,20-26] that identified the clinical question associated with the diagnosis/diagnostic test,were classified as level VI.

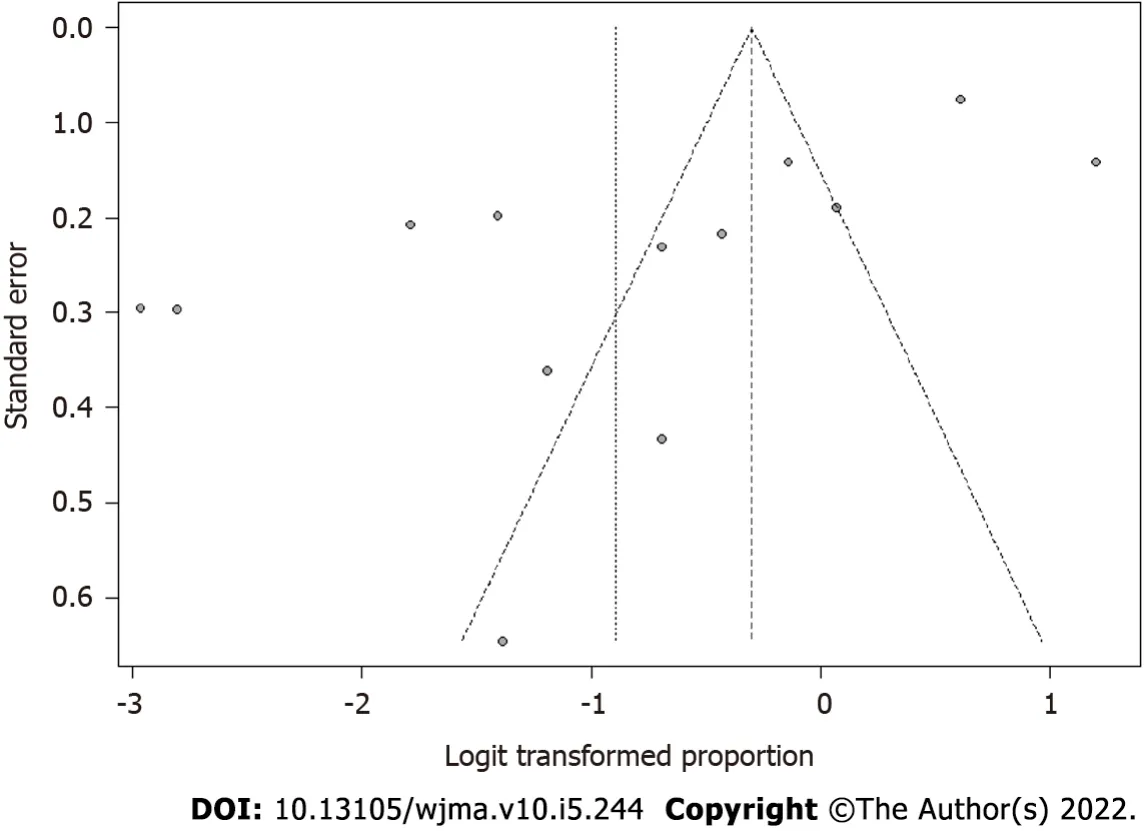

Due to the asymmetry of the points,we did not identify publication bias (Figure 2). We observed a proportion of 0.29 with a confidence interval of 0.18 to 0.44 and a significantPvalue representing almost 30% of the analyzed cases (Figure 3).

Figure 2 Study proportion meta-analysis.

Figure 3 Publication bias analysis.

DISCUSSION

We have concluded that the most used psychometric scale for analyzing eating behaviour and risk for ED is The Diabetes Eating Problem Survey-Revised (DEPS-R).

Previous research showed that patients with DT1 have a higher frequency of ED and nutritional risk behaviours than the standard population[20]. For sure,these disorders contribute to an increased risk of complications from diabetes,such as abnormal lipid profiles,diabetic ketoacidosis,retinopathy,neuropathy,nephropathy,and mortality increase[11,27,28]. Therefore,evaluating these clinical conditions for follow-up and damage reduction with the subjects’ effective participation is relevant[29].

A study evaluated risks of eating disorders using the following tools: The Eating Attitude Test (EAT-26),The Bulimic Investigation Test of Edinburgh (BITE),and the Binge Eating Scale (BES). It showed that the percentages of patients at risk of eating disorders were 45% per EAT,40% per BITE,and 16% per BES[20]. These tools evaluated a specific type of disorder. Although of great value,they are not directed to patients with DT1,but to the standard population.

Researchers affirmed that ED are characterized by significant hassles in the cognition of the body's image and morbid concern with food,weight,and shape. Adolescents,when trying to control their weight,appeal to behaviours that include self-starvation,self-induced vomit,abusive use of laxatives and diuretics,and a tremendous and significant volume of physical exercise[15].

One considers habits such as the restriction or omission of insulin as an exclusive disorder eating behaviour of people with DT1. They are usually considered boundary conditions to an eating disorder because their symptoms have yet to reach a threshold of high degree. Such conditions would be classified as an eating disorder as such[8,30].

A study involving adolescents with DT1 demonstrated that a higher body mass index (BMI) was significantly associated with a less positive body image among girls with diabetes. This data emphasizes that higher BMI is associated with low self-esteem and lower levels of social support among adolescents with diabetes,especially girls. Another addition is that worries about body image and several psychosocial factors can be forerunners to developing eating disorder symptoms[31].

Instruments capable of validating the eating disorder must be projected to combine the participants’cognitive capacity and the adolescents’ development stage. Researchers from Norway observed that no evaluation measures for ED were available to the younger population. Therefore,they used an adaption of the EDE 12.0 tool,which is recognized as a gold standard measure of psychopathology about ED among adults[32]. For this,they adapted and evaluated the psychometric properties of the Norwegian version of the “ChEDE” for children and adolescents[15].

It is worth highlighting that adolescents with DT1 usually have a complicated state of worries around eating and diet but generally are not associated with weight and body shape issues. This finding confirms that the ChEDE tool could distinguish eating problems in this group and cognitive and behavioural psychopathology in anorexia[15].

Another study in Norway to evaluate DEB adapted and validated the DEPS-R with children and adolescents with DT1. When comparing the DEPS-R with the EAT-12,the DEPS-R seemed to be a better screening tool for DEB among young patients with DT1. In addition to the internal consistency,the DEPS-R was strongly correlated with glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c),rather than EAT-12,although both correlations were presented as relatively weak. Overall,male adolescents reported fewer DEBs than female ones[19].

Concerning the risk of ED,a study analyzed it using the mSCOFF tool,an adaptation of the SCOFF,for people with DT1. The tool mCOFF was adapted and evaluated for the risk of ED among female adolescents with DT1[21]. The researchers affirmed that when the mSCOFF tool was applied to 43 female adolescents with DT1,compared with the mEDI instrument,10 (23.2%) participants were identified as being at high risk of developing an eating disorder[21].

In other studies that investigated ED in a similar population,the female participants presented more elevated results compared to male participants. The studies[15,21] showed these results as intrinsically connected to personal dissatisfaction with body image. Such an issue is the one the girls report the most.It is stated that the genesis and occurrence of ED can diverge between boys and girls,and the prevalence in male adolescents with DT1 is low[33].

One study highlights another tool to analyze the DEB in children and adolescents with DT1 – DEPSR. Researchers from the USA used a DEPS adapted tool developed for adults with DT1[25]. Such specific tools for diabetes are needed due to the inefficient use of insulin and a potential purgative behaviour. These issues are seen as exclusive to individuals with diabetes[34]. The DEPS-R can avoid developing ED,such as bulimia and anorexia.

Therefore,the DEPS-R tool was adapted and validated in several countries,and a study[8] evaluated the prevalence of DEB in the region of Marche,Italy,through the use of the Italian version of the DEPSR for the screening adolescents with DT1. The finding indicates a significantly higher prevalence (a score of ≥ 20 DEPS-R of 34.4%),among patients with overweight (65.7%). It was also identified that the participants with a score ≥ 20 in the DEPS-R had significantly higher levels of HbA1c,used higher doses of insulin,and spent less time doing physical exercise.

Researchers observed that there was no instrument planned to support health professionals in identifying DEBs in the French adult population with diabetes. Due to this,there was a need to adapt and validate the DEPS-R. Therefore,a study was performed to validate the DEPS-R tool in adolescents and adults with DT1 and DT2[17].

The study aforementioned adapted and validated the tool to compare it with the following instruments: The Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q6)[35] and Eating Disorder Inventory 2-Body (EDI-2)[36]. However,the study found significant barriers and limitations,one of which was the reduced participation of adolescents. Thus,the adults prevailed. In addition to this,different constructs of body dissatisfaction could be used to provide more empirical support for the tool The Questionnaire des Attitudes et des Comportements liés à la gestion du Diabète (QACD). This study’s innovation was the use of a tool for a heterogeneous public,where there were adolescents and adults diagnosed with DT1 and DT2[17].

The Turkish version of the DEPS-R adapted and validated this tool for children and adolescents with DT1[22]. The results have shown that 25% of the participants had a score of DEPS-R ≥ 20. Of these,most were women,and the patients with a score ≥ 20 were not adequately using their insulin to fulfill the demand from the meals at times where they ate beyond what is recommended; a few skipped the follow-up dose of insulin after overeating.

In Germany,researchers adapted and validated the DEPS-R for adolescents with DT1. They reported that the insulin restriction or its omission reported to the doctor seems not to be insufficient to the identification of ED. The disordered behaviour may come accompanied by feelings of shame and guilt,which can be a barrier for adolescents to talk about their eating behaviours[23].

For the Italian population,a study used the DEPS-R adapted and validated with patients with DT1 and DT2,aged between 13 to 55 years old,being treated with insulin. In general,21.8% of the sample met the conditions for at least one diagnosis of DSM-5 eating disorder,and 12.8% met the conditions for at least one diagnosis of DSM-IV eating disorder[26]. Moreover,in China,a study adapted and validated the DEPS-R in adolescents aged 8 to 17 years old with DT1 and 61 adults with DT1. It was registered that the average score of C-DEPS-R was 21.0. The high risk of DEBs among adolescents in this study was 39.3%[18].

Another tool that evaluated the risk of DEB is the Eating Attitudes Test-26 (EAT-26),which had a valid,sensitive,and specific measure to detect individuals at high risk for a diagnosable eating disorder.The researchers used the tool EAT-26 in eight cases in a group of healthy brothers. Three were diagnosed with DEB,and one case with anorexia nervosa. In the control group,five cases had a pathological score,where three of these cases were diagnosed with DEB. From this control group,no case was diagnosed with an eating disorder[16].

Norwegian researchers[24] developed and validated the tool “MIND Youth Questionnaire (MY-Q)”for adolescents with DT1. The tool adopted the following domains: Family functioning,depression symptoms,and disordered eating. The multidimensional survey consists of seven subscales (social impact,country,control perceptions of diabetes,responsibility,worries,satisfaction with the treatment and body image,and eating behaviour). The results showed that the body image had a higher association with what was disclosed by the female group,in contrast to what the male group verbalized.

It was observed that the common ground of all research is the fact of applying the tools and evaluating some critical variables related to DT1,such as BMI evaluation,HbA1c,and insulin use,to ascertain the possible metabolic changes and DEB. A study[37] quoted the importance of analyzing the sociodemographic data with emphasis on the age group and sex as relevant variables to correlate with BMI and HbA1c.

Another observation is related to the age group and the type of diabetes. A study[15] explored a younger public beginning at nine years old with DT1. In contrast,another study[17] explored a younger public and adults with an age limit of 84 years old with DT2. Therefore,the tools have shown themselves as essential for identifying DEB or ED of adolescents and adults afflicted by DT1,thus possibly contributing to the prevention of possible complications related to this type of grievance.

It is essential to highlight some limitations of this review before any external generalization. The analyzed studies did not employ the same psychometric instrument in all their investigations. Overall,the authors employed four different scales,however,in the same population: Adolescents with DT1.Even though we have conducted a broad sweep of the central databases,publication bias is possible because some industry pharmaceuticals privately own some scales. In this point of view,the scales can be marketed to the public and are not necessarily published in scientific journals.

CONCLUSION

Based on the scales analyzed,we concluded that adolescents with DT1 achieve high scores that indicate risk for eating behaviour and ED. Both eating phenomena are related to variables such as female gender,BMI,and HbA1c in adolescents with DT1.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Oliveira Cunha MCS,Queiroz MVO,and Moura de Araújo MF designed the study; Dutra FCS,Cavaleiro Brito LMM,Sousa DF,Gaspar MWG,and Costa RF performed the study equally,contributed to the extraction of the data,analyzed the data,wrote the paper,and approved the manuscript; Oliveira Cunha MCS,Queiroz MVO,and Moura de Araújo MF critically reviewed and approved the final draft and are responsible for the content and similarity index of the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors deny any conflict of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist in detail,and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license,which permits others to distribute,remix,adapt,build upon this work non-commercially,and license their derivative works on different terms,provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Brazil

ORCID number:Maria Conceição Santos Oliveira Cunha 0000-0002-6805-6137; Francisco Clécio Silva Dutra 0000-0002-3451-1664; Laura Martins Mendes Cavaleiro Brito 0000-0001-6495-045X; Rejane Ferreira Costa 0000-0002-7436-7812; Maria Wendiane Gueiros Gaspar 0000-0003-1452-7180; Danilo Ferreira Sousa 0000-0001-9281-165X; Márcio Flávio Moura de Araújo 0000-0001-8832-8323; Maria Veraci Oliveira Queiroz 0000-0002-7757-119X.

S-Editor:Liu JH

L-Editor:Wang TQ

P-Editor:Liu JH