Endoscopic techniques for diagnosis and treatment of gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms:Where we are

2022-07-30RossiREElveviGalloPalermoInvernizziMassironi

Rossi RE, Elvevi A, Gallo C, Palermo A, Invernizzi P, Massironi S

Abstract

Key Words: Gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms; Endoscopy; Ultrasound endoscopy;Capsule endoscopy; Double-balloon enteroscopy; Diagnosis; Therapy; Staging

lNTRODUCTlON

Gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs) represent heterogeneous and rare tumors, whose incidence has been progressively increased in the last decades[1]. The prognosis of these neoplasms is widely variable depending on several factors including the site of the primary tumor, the grading as assessed by the specific WHO classification, and the stage as classified in a specific TNM system[2]. It is therefore clear that the correct localization of the primary tumor site, as well as a complete histologic diagnosis, represent the milestones for the proper management and the prognosis of these tumors[3-5].

In this scenario, despite advances in radiological and metabolic imaging, standard axial endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) still play a pivotal role in several GEP-NENs. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is essential for the detection and characterization of esophageal, gastric,and duodenal NENs. Ileocolonoscopy allows the assessing and diagnosing of rectal, colonic and rarely distal ileal lesions. Small bowel NENs have proven difficult to diagnose, given their nonspecific presentation and poor accessibility of the distal small bowel to common endoscopic techniques. The diagnosis of small bowel NENs (sbNENs) has been largely improved with the advent of video capsule endoscopy (CE) in 2000 and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), the most promising device-assisted enteroscopy (DAE) system, in 2001, which allow for direct visualization of the entire Sb[6]. Finally, EUS is the modality of choice for both diagnosing pancreatic NENs and for the locoregional staging of several NENs, including gastric, duodenal, pancreatic and rectal NENs; of note, in the setting of pancreatic NENs (panNENs), it has demonstrated higher accuracy in tumor detection than other imaging modalities[7].

The present review is aimed at analyzing current evidence on the role of endoscopy in the management of GEP-NENs, with a specific focus on CE and DBE for sbNENs and EUS for the diagnosis and staging of panNENs and other NENs. Furthermore, we summarized available evidence on the role of endoscopy in the radical treatment of selected GEP-NENs.

MATERlALS AND METHODS

An extensive bibliographical search was performed in PubMed to identify guidelines and primary literature (retrospective and prospective studies, systematic reviews, case series) published in the last 15 years, using both medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and free-language keywords: gastro-enteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms; endoscopy; ultrasound endoscopy; capsule endoscopy; doubleballoon enteroscopy; diagnosis; therapy; staging. The reference lists from the studies returned by the electronic search were manually searched to identify further relevant reports. The reference lists from all available review articles, primary studies, and proceedings of major meetings were also considered.Articles published as abstracts were included, whereas non-English language papers were excluded.

RESULTS

A total of 448 records were reviewed and 84 were defined as fulfilling the criteria for final consideration.Figure 1 presents the flow chart showing the process of study selection.

DlAGNOSlS

Ultrasound endoscopy (EUS)

EUS represents the diagnostic gold standard for panNENs and the technique of choice for the locoregional staging of gastric, duodenal and rectal NENs. According to the latest European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) Consensus guidelines, EUS proved to be the most accurate diagnostic technique in panNENs detection, leading to an up-to-94% sensitivity[8]; PanNENs usually appear rounded and homogeneously hypoechoic at EUS examination (Figure 2). EUS sensitivity in detecting panNENs is even higher than noninvasive computed tomography (CT)-scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)pancreatic lesion detection rate[9]. EUS is also extremely accurate in locating the lesions, even very small ones, within the pancreatic parenchyma, and it can describe the distance between the lesion and the main pancreatic duct, which represents an independent predictor of aggressive tumor behavior and of developing pancreatic fistulas[10]. EUS overall complication rate is about 1%-2%, higher for pancreatic cysts rather than for solid masses[11].

Advanced EUS techniques allow to study specific morphological and histological details of the detected lesions that may be helpful in the differential diagnosis of panNENs and in the choice of the corresponding best-suited treatment[7]. Contrast-enhanced harmonic EUS (CH-EUS) allows real-time visualization of parenchymal perfusion and, thus, helps in distinguishing hypovascular carcinomas from hypervascular less aggressive lesions. It consists of harmonic detectors that register microbubbles produced by contrast agents administrated intravenously; this method allows the identification of microvessels even with slow blood flow[12]. As demonstrated for nonfunctioning panNENs, the CHEUS vascular pattern of neuroendocrine lesions represents an indirect reliable surrogate predictor of their aggressiveness and, thus, of their prognosis; a statistically significant positive correlation was, in fact, proven between the inhomogeneous sonographic pattern of the lesions and their Ki67 proliferative index, which in turn represents the most reliable independent predictor of malignancy. Sonographic heterogeneity at CH-EUS, and especially hypoenhancement in the early arterial phase, corresponds to lower intratumoral microvascular density and to a greater degree of fibrosis on pathological specimens,which were demonstrated to be typical features of tumor aggressiveness on a par with tumor grading[13]. According to a Japanese retrospective study[14], hypoenhancement at CH-EUS proved to be a reliable predictor of tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis also for G1 and G2 panNENs, with sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value and accuracy of 94.7%, 100%,100%, 96.6% and 97.9%, respectively.

EUS-fine needle aspiration (FNA) is another diagnostic advanced EUS technique, which represents the gold standard least invasive option to obtain the histological identification of a suspected pancreatic neoplasm or peripancreatic lymph nodes, with a sensitivity ranging between 80% and 90% and a specificity of nearly 96%[15] (Figure 3). It is also the operative technique of choice to aspirate the contents of cystic lesions for serological analysis and for the tumor marker dosage, which might help in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lesions. It can be performed with different diameter needles, mainly depending on the type and site of the lesion, its consistency, and echogenicity. There are several techniques described, which make different use of the suction: some of them suggest not to apply any suction due to the high risk of contaminating the specimen with blood (especially in case of highly vascularized lesions), some others apply wet or dry negative-pressure suction to guarantee sufficient material for histological diagnosis, and others again proposed a slow-pull fanning technique to ensure at the same time a greater collection of pathological cells and a low blood contamination risk[16]; to date, even if still no consensus has been reached on the optimal strategy, overall FNA-EUS sampling adequacy rates up to 94%[17,18] and its diagnostic sensitivity proved to be significantly higher than CT and/or MRI specifically in case of solid, cystic and combined solid-cystic panNENs (84%vs42%, 70%vs10% and 81%vs36% respectively)[19].

Figure 1 The flow chart showing the process of study selection.

Figure 2 Endoscopic appearance at endoscopic ultrasound of a pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm with marginal vascularization.

The Ki-67 index histological expression of the suspected pancreatic lesion plays a fundamental role in defining the aggressiveness of the tumor, together with its radiological aspect, its localization and distance from the pancreatic duct, and its CH-EUS vascular behavior. Therefore, the Ki-67 index also drives the choice of the best-suited therapeutic approach. Data about the concordance rate between EUS-FNA and surgical specimens in terms of G1, G2 or G3 panNEN and G3 pan-neuroendocrine carcinoma differentiation based on the Ki-67 index are discordant, ranging from a 78% of accordance rate (k-statistic: 0.65)[10], to a relatively significant discrepancy, especially for G2 lesions[20]. This discordance may be first attributed to the fact that endoscopic sampling of large lesions > 20 mm, often included in the studies available to date, may not be representative of the area with the highest concentration of malignant cells and, thus, that the measured Ki-67 index might be not indicative of the most proliferative area of the neoplasm. There is a strong necessity for further studies that subclassify more accurately the included lesions depending on their size.

Figure 3 Endoscopic appearance at endoscopic ultrasound of a pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasm located at the tail of the pancreas during fine needle aspiration/biopsy procedure.

New EUS needle acquisition techniques (i.e., 19/22/25- G ProCoreTM needle, Cook Endoscopy,Winston-Salem, NC, USA; 19-G fine-needle biopsy, Cook Endoscopy Inc., Limerick, Ireland; Acquire®Endoscopic Ultrasound Fine Needle Biopsy (FNB) Device 22/25-G, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA;SharkCoreTM, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland) have been proposed to overcome the rare cases of EUS-FNA inadequate tissue sampling; these devices are designed to maximize tissue capture and minimize bleeding and tissue fragmentation and some of them are thought to provide both cytological and histological sampling[21]. However, further studies are needed to validate these approaches in the specific setting of NENs.

EUS real-time elastography (EUS-RTE) allows not only a qualitative but also a quantitative assessment of the elasticity of the suspected pancreatic lesion compared to the one of the normal surrounding pancreatic parenchyma. Based on the evidence of higher tissue stiffness in the case of malignant lesions when compared to the normal parenchyma[22], some authors have proposed different quantitative elastography cutoffs to stratify the risk of malignancy. Havreet al[23] observed a EUS-RTE sensitivity of 67% and specificity of 71% in detecting pancreatic malignant lesions with a strain ratio cutoff of 4.4. Iglesias-Garcíaet al[24] showed an EUS-RTE sensitivity of 100% and specificity of 88% in differentiating specifically pancreatic adenocarcinomas from panNENs with a 26.6 strain ratio cutoff value. Even if, according to the European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) guidelines, EUS-RTE cannot yet replace the histo-cytopathological diagnosis of carcinoma[25], this technique may facilitate the differentiation from benign to malignant pancreatic lesions.

Another advanced technique in EUS that can drive in the diagnostic orientation is represented by the needle-based confocal laser endomicroscopy, which allows the real-time directin vivovisualization of the histological aspect of the GI mucosa overlying pancreatic NENs, which is traditionally described as clusters of compact cells on a dark background surrounded by numerous small and irregular vessels and fibrotic areas[26]. Giovanniniet al[27], observed a negative predictive value of 100% for the characterization of pancreatic NENs in EUS needle-based confocal laser endomicroscopy; therefore supporting the concept that it cannot be considered as an alternative to the histological diagnosis, but that it may help to rule out malignancy.

Further applications of EUS in panNENs is represented by the preoperative EUS-guided fine-needle tattooing and EUS-guided fiducial implantation, which may help surgeons find little pancreatic lesions during laparoscopic surgery, limiting the laparoscopic resection to the lesion itself, sparing the normal surrounding parenchyma, and reducing the operating time[28].

As regards GI-NENs, EUS mainly plays a diagnostic and staging role; its sensitivity in detecting GINENs is up to 94%[29]; they usually appear as submucosal rounded, hypoechoic, well-demarcated lesions and can be detected when smaller than 10 mm, especially rectal NENs thanks to the growing sensibility to colorectal carcinoma screening. According to the ENETS most recent guidelines, in case of the endoscopic identification of a GI lesion that is compatible with a GI-NEN, EUS is recommended in case of lesions > 10 mm in order to study the depth of the lesion, to stage the hypothetical presence of locoregional lymph nodes and, thus, to drive the choice of the most appropriate endoscopic or surgical treatment[30]. Less than 10 mm GI-NENs, in fact, have a low risk of both lymphatic invasion and distant metastases, which is reported to be 1%-2%[31]. GI-NENs measuring 10-19 mm at their first endoscopic diagnosis deserve more accurate EUS evaluation because of the reported higher incidence rate of lymph node invasion or distant metastases, leading up to 5%-15%[32]. If the GI-NEN is limited to the submucosa and does not invade the muscularis mucosae (which corresponds to a T1 lesion), regardless of its lateral spreading, a simpleen blocendoscopic resection treatment has proved to be effective in guaranteeing a radical resection and a very limited recurrence rate during the follow-up[33], otherwise,a surgical approach is suggested. T2 or N+ stage lesions should be accurately studied with total body imaging such as 68-Ga-DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET) and a CT scan in order to plan the best therapeutic approach.

Capsule Endoscopy (CE) and Double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE)

The small intestine is the most common NEN site in humans. Historically, sbNENs have proved difficult to diagnose because of both the lack of specific symptoms at presentation and the poor accessibility of the distal small bowel[34]. Conventional radiology (both CT and MRI either in the standard technique or in combination with enteroclysis) are often not accurate enough in the detection of sbNENs[35], whereas PET/CT with 68Ga-DOTA peptides remains the most sensitive modality in the detection of well-differentiated NENs, although it does not allow to get a histological diagnosis and might not be fully accurate in the anatomical location of the primary tumor being, for instance, unable to differentiate between intestinal and mesenteric localization[36]. Furthermore, in the case of metastatic disease, the detection of the primary tumor is recommended in both resectable and non resectable diseases.However, in up to 10% of the cases after the discovery of liver or lymph node metastases, the primary tumor site remains unknown despite an extensive workup[35].

With the advent of CE and DBE the diagnosis of sbNENs has improved, even if data regarding the efficacy and safety of these techniques in the detection of sbNENs are scanty and mainly based on small retrospective series, given the rarity of the disease and the still-limited use of these techniques in routine clinical practice. Most of the available studies are focused on small bowel tumors in general and only a small percentage of included patients displayed an sbNEN[37-39]. In a study comparing CT, enteroclysis, nuclear imaging, and CE of the small bowel[34], CE showed a high diagnostic yield (45%) in identifying primary tumors. Of note, in 12 of 20 patients (60%), CE showed small-intestinal lesions that were then confirmed histologically as NEN in six of seven patients who underwent surgery.

When considering the few studies specifically focused on NENs, the results came back to be inconclusive. In a retrospective study by Frillinget al[40], including 390 patients with metastatic NENs of whom 11 with unknown primary tumor, CE identified lesions suggestive of small bowel primary in 8/10 patients in whom it was successful, and these tumors were all histologically confirmed. In a recent prospective study[41], the diagnostic yield of CE was reported to be limited. In 24 patients with a histological diagnosis of metastatic NEN of unknown origin, CE, which was preferred to DBE as less invasive and less expensive, was requested before explorative laparotomy and its diagnostic yield was compared to the surgical exploration. CE identified a primary sbNEN in 11 subjects. However,diagnosis of sbNEN was confirmed only in five (41%) cases after surgical and ultrasound exploration were performed. The high number of false-positive results could have been related to small bowel contractions, extrinsic compression, lymph stasis, or submucosal lesion of another type.

Although CE is less invasive, DBE is necessary for determining the precise location, number of tumors, and pathological diagnosis; it can be carried out through the oral (antegrade) or the anal(retrograde) route and with a combined oral and anal approach[42]. Belluttiet al[43], in a study involving 12 consecutive patients with suspected sbNEN or with liver NEN metastases, who underwent DBE, found a diagnostic yield of DBE for primary tumor of 33%. In a case series by Scherublet al[44],five consecutive patients with metastatic midgut carcinoids underwent DBE and an NEN of the ileum was detected in four of the five patients; the histopathological evaluation of their biopsy specimens confirmed the diagnosis revealing well-differentiated NENs. Conversely, conventional radiological imaging did not visualize any of the primary tumors.

In our recent prospective study[45], we reported sensitivity and specificity of 60% and 100%,respectively for DBE in detecting sbNEN in six patients with unknown primary, showing that DBE is a safe and effective procedure in diagnosing sbNENs. We suggested that when a sbNEN is suspected,DBE should be taken into account as an accurate diagnostic tool in order both to collect biopsies for final diagnosis and to make tattoos before surgery; of note, DBE should be preferred over CE in the presurgical setting given the high specificity. Considering the limited available data, further studies are needed to better define the actual role of CE and DBE in the diagnosis of sbNENs.

TREATMENT

Gastric NENs

Gastric NENs (gNENs) are usually subclassified into three types, according to their pathophysiology and behavior[29,46].Type I tumors correspond to the majority of gNENs (~80%) and are associated with autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Histologically, type I gNENs are composed of enterochromaffin-like cells. The diagnosis is made by upper digestive endoscopy with biopsy. The majority of type I gNENs present as small, multiple tumors, located in the gastric body or fundus, and limited to the mucosal or submucosal layers of the stomach wall[46,47]. Since the risk of metastasis is < 5% in type I gNENs, a conservative approach based on endoscopic follow-up with lesion resection is advised for this kind of tumor. The treatment of choice for type I gNENs is endoscopic resection for lesions > 0.5 cm and endoscopic surveillance for lesions < 0.5 cm[46,48,49].This approach has been shown to be safe and effective in a prospective series of 33 type I gNENs, with no significant procedure-related complications,no development of metastases, and a 100% long-term survival rate[50].

The ENETS guidelines[29] suggest performing EUS in case of lesions > 1 cm. Staging EUS is frequently performed to confirm the appropriateness of endoscopic resection, which applies to lesions not infiltrating beyond the muscularis propria[7].For lesions > 1 cm, EUS is excellent for determining the exact tumor size and for excluding infiltration of the type I gNENs into the muscularis propria (T2)or enlarged regional lymph nodes[47,51].

Type II gNENs correspond to 5%-10% of gNENs; they usually develop when multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 is present and are often associated with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome[46,48]. Like type I gNENs, type II gNENs originate from enterochromaffin-like cells. They are small, multiple, and relatively benign tumors, even though about 10%-30% of patients present as metastatic at the diagnosis[52]. For type II gNENs local excision is recommended, preferentially by endoscopy; as well as for type I gNENs, EUS plays a pivotal role in determining the tumor size, lymph node involvement, and depth of invasion; endoscopic treatment is again reserved for lesions not infiltrating beyond the muscularis propria, without lymph node involvement[7,53].

Type III gastric NENs are usually larger sporadic tumors with an infiltrative and metastatic tendency and account for 15% of all gNENs. They are generally characterized by being single lesions, > 1 cm and with a greater likelihood of evolving to regional and systemic metastases, as more than half of patients with type III gNENs are metastatic at diagnosis, mainly to the liver[46,48]. From a therapeutic point of view, surgery is the standard treatment,i.e., total or subtotal gastrectomy together with lymphadenectomy, as recommended in gastric adenocarcinoma. For patients with any surgical contraindication,endoscopic resection may be an alternative, but the risk of regional lymph node spread remains high[46]. Of note, in selected cases of small (< 1 cm) type III G1/G2 (Ki-67 < 5%) gNENs fully resected (R0)by endoscopy with no risk factors for metastatic disease, endoscopic resection might be sufficient[54].As for other gNENs, EUS is a useful tool for locoregional staging, particularly to stage the disease by assessing the presence of regional lymph node involvement.

Conventional polypectomy with a snare for flat mucosal lesions should be avoided because complete resection is often not achieved. Early gNENs are generally removed by endoscopic mucosal resection(EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)[47,54]. In EMR, snare resection is preceded by the submucosal injection of saline in order to raise the tumor and cut into the submucosa below the tumor[47]. ESD is preferred over EMR in case of suspicion of limited submucosal invasion or a tumor > 2 cm[55]. After submucosal injection of saline, the submucosa is dissected with specific knives in order to achieve endoscopicen blocresection of the whole neoplasm.

The resected specimen has to be carefully evaluated regarding grade, angioinvasion, and infiltration of the deep resection margin. In case of angioinvasion, histological infiltration of the muscularis propria(T2), or grade G2/G3, radicalization with surgery with lymph node dissection is the therapy of choice in localized neuroendocrine disease[47].

Duodenal NENs

Duodenal NENs (dNENs) are rare, usually small well-differentiated tumors in most of the cases;however, according to a recent multicenter retrospective study[56], dNENs’ prognosis may be highly variable as these tumors can be metastatic in up to 50% of the cases at the time of first diagnosis and can develop metastases thereafter. Upper GI endoscopy with biopsy is necessary for dNEN diagnosis and EUS should be performed to assess the local extent of tumor depth.

In view of this heterogeneous behavior, surgical resection has been suggested as the preferred treatment modality over endoscopic treatment, and surgery is generally recommended for ampullary dNENs and lesions > 2 cm in size[38]. Endoscopic resection is the treatment of choice for well-differentiated localized nonmetastatic tumors with a diameter < 1 cm and confined to the submucosa layer and the rationale for preferring the endoscopic treatment for tumors < 1 cm relies on the fact that they seem to have a low rate of nodal disease[57]. In this setting, there is no current evidence to prefer an endoscopic approach over another as prospective studies comparing the available techniques (i.e., ESDvsEMR) are lacking.

However, there is still controversy regarding the management of tumors between 1 and 2 cm, which is mainly based on the tumor location and the presence of nodal involvement on imaging. According to some authors, > 10% of patients with dNENs < 1 cm in size develop lymph node metastases, thus suggesting the need for a radical surgical approach for all dNENs despite the size of the primary tumor[58-60]. Another issue to be taken into account is the high risk of conventional and functional imaging of understaging mainly due to the presence of nodal and distant micrometastases[60]. These results represent a sign of warning for conservative approaches including endoscopy, suggesting as a possible strategy, the inclusion of EUS in the preoperative phase, although prospective studies are necessary to draw solid conclusions.

In summary, all considered, endoscopic resection either EMR or ESD should be reserved for dNENs <10 mm, limited to the submucosal layer without evidence of lymph node or distant metastases, whereas surgery might be advised for dNENs > 10 mm with evidence of muscular layer invasion or nodal involvement. EUS should be encouraged for all dNENs in order to plan the best therapeutic approach.

Rectal NENs

Endoscopic treatment for rectal NENs (rNENs) is indicated if there is no evidence of invasion beyond submucosa and presence of locoregional disease since it aims to achieve a complete oncological resection[61].

The ENETS guidelines[30] suggest that well-differentiated (G1/G2) rNENs that are < 10 mm in stage T1 and T2 and rNENs between 10 and 20 mm in stage T1 without lymph node metastasis should be removed endoscopically. On the contrary, surgical resection is indicated in cases of G3 rNENs, 10-19 mm with muscolaris propria invasion (stage T2) and for tumors > 20 mm and/or in presence of lymph node metastases.

Endoscopic techniques for treating rNENs include standard polypectomy, EMR, modified EMR, ESD,and endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR). Standard polypectomy does not offer an adequate and complete resection of the lesion; therefore, it is not indicated in rNEN treatment[62]. Of note, a large number of rNENs is still removed by an improper method, such as routine snare polypectomy, during colorectal cancer screening making management more complex and putting patients at risk of metastatic spread[63].

EMR is largely used in the resection of small and superficial neoplasia confined to the mucosa and submucosal layer, but its application in rNENs is still debated since modified EMR and ESD are superior in terms ofen blocresection rate and histological complete resection rate (defined asen blocresection with no margin involved)[64,65].

Recently, Parket al[66] observed that when EMR is performed underwater, the histological complete resection rate of NENs < 10 mm is similar to that for ESD (86.1%vs86.1%, respectively) but with a shorter procedure time (5.8 ± 2.9vs26.6 ±13.4 min, respectively).

EMR performed with a dual-channel endoscope allows deeper resection compared to conventional EMR by lifting the lesion with forceps. Leeet al[67] observed that dual-channel EMR reaches a complete histological resection rate similar to that of ESD for rNENs < 16 mm (86.3vs88.4 %, respectively), but with a shorter procedure time (9.75 ± 7.11vs22.38 ± 7.56 min, respectively) and fewer complications.

Modified EMR techniques include the use of special devices that allow better resection of the tumor.EMR after circumferential precutting (EMR-P) is performed by lifting the submucosal with saline injection, precutting using the tip of the snare or special endoknife and resecting the tumor with a snare.Cap-assisted EMR (EMR-C) is performed by lifting the mucosa with saline injection, suctioning the lesion with a transparent cap fitted to the scope and then removing it with a snare looped along the ridge of the cap. EMR with a ligation device (EMR-L) is conducted by lifting the lesion with saline injection, deploying an elastic band around its base, and resecting with a snare. Histological complete resection rate for EMR-P is superior to EMR and no difference was found between EMR-P and the other modified EMR techniques, even if it required a longer procedure time[68]. Parket al[69] demonstrated that EMR-C is a safe and effective technique for rNENs, with a histological complete resection rate even better than that of ESD (92.3%vs78.4%, respectively).

EMR-L is only applicable for tumors of < 10 mm due to the short diameter of the caps fitted to colonoscopes, but it is significantly superior to EMR in terms of complete resection of rNENs (93.3%vs65.5%,respectively), regardless of the tumor location[70]. Histological complete resection rate is similar between EMR-C and EMR-L. However, Leeet al[71] demonstrated that EMR-L might be preferable for achieving a higher rate ofen blocresection (100%vs92.9%, respectively), but this could be due to the fact that the band thickness used in EMR-L is larger than the snare thickness of EMR-C.

ESD is an interventional procedure suitable foren blocresection of slightly invasive GI lesions. After injection of the submucosal with a viscous solution, an endoknife is used to incise the mucosa surrounding the lesion and to dissect it from the submucosal layer. ESD is an effective technique to treat rectal lesions, even if it is associated with a high risk of complications and a long procedure time. As it concerns rNENs, ESD has been demonstrated to be superior to EMR in terms of histological complete resection rate, but there are no significant differences between ESD and modified EMR[70].

Niimiet al[72] observed that ESD is associated with a longer procedure time and hospitalization period compared with EMR-L, with a similar complete resection rate. In order to reduce procedure time,Wanget al[73] proposed a hybrid ESD, in which the mucosal incision is performed with a polypectomy snare instead of an endoknife. This technique showed a similaren blocresection rate (99.2%vs98.2) and complete resection rate (94.1%vs90.9%) to ESD but with a shorter procedure time (13.2 ± 8.3vs18.1 ±9.7 min).

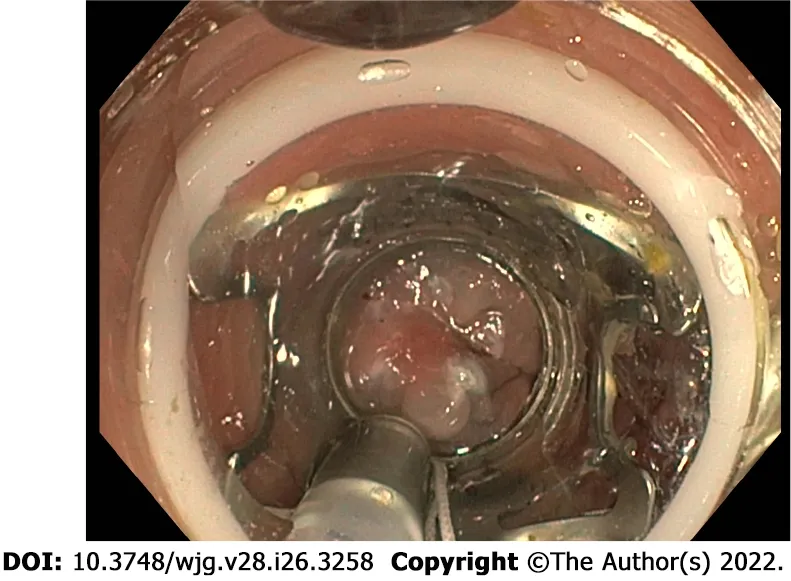

EFTR is a technique mainly used in lesions that are difficult to resect and its application in rNENs has recently been proposed. A full-thickness resection device is fitted over the scope and, after placement of a modified over-the-scope-clip, allows a single step EFTR (Figure 4).

Meieret al[74] collected data on 40 EFTRs in rNENs and observed that resection was macroscopically and histologically complete in all cases without major events, but prospective comparative studies between different resection techniques are still missing.

To conclude, rNENs < 10 mm should be treated endoscopically, and EMR-L should be considered as the first-line treatment; ESD can be used as second-line therapy when EMR-L is not applicable. EFTR can be an effective and safe technique in lesions that are difficult to treat. Treatment of rNENs with a size of 10-19 mm should be chosen after assessing the stage and the grade of differentiation.

Figure 4 Over-the-scope clipping system for endoscopic full-thickness resection of a rectal neuroendocrine neoplasm.

pancreatic NENs

In recent years there has been a great development of EUS techniques, not only used as diagnostic, but also as therapeutic tools. These methods find application in the management of panNENs, given the direct approach to the pancreas through the echoendoscope. The incidentally discovered small panNENs, mainly nonfunctional, represent a therapeutic challenge because surgery could be very complex in the face of neoplasms with indolent biological behavior, and active surveillance may represent an option for G1 or low G2 neoplasms, asymptomatic, mainly localized in the head of the pancreas, without radiological signs suspicious for malignancy[8,75]. In this setting, however, EUSguided pancreatic locoregional ablative treatments, using either ethanol injection or radiofrequency ablation, have been proposed in recent studies with promising results in order to control symptoms or reduce tumor burden in selected patients[76]. The thermoablative techniques are the most used, mainly the radiofrequency methods. EUS-guided radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is reported to be a potentially effective and safe treatment for Pan-NENs[77].

Several RFA devices for EUS-guided applications are currently available. The Habib EUS-guided RFA probe (EndoHPB, EMcision UK, London, UK) is a 1 Fr (0.33 mm), monopolar catheter, which can be inserted through a regular 19- or 22-gauge FNA needle and connected to a standard radiofrequency generator. The other systems are needle-electrodes, and the most commonly used in literature is the one from Taewoong Medical (EUSRA, Taewoong Medical Co. Ltd., Gimpo-si, Geyonggi-do, South Korea),an 18- or 19-gauge needle with a long electrode lacking insulation over the terminal tip, connected to a dedicated RF current source, and an inner cooling system that circulates chilled saline inside the needle to avoid tissue charring. Under the EUS guide, the needle is inserted into the target lesion that is being treated by using high-frequency alternating current, and the energy release is applied when the needle tip of the electrode is within the lesion, while maintaining a distance of at least 2 mm from the pancreatic and bile ducts and vessels, to avoid injury or duct strictures. A recent systematic literature review explored the feasibility, effectiveness, and safety of EUS-RFA in the treatment of panNENs[94]:12 articles describing 61 patients and 73 panNENs were analyzed and the overall effectiveness of EUS-RFA resulted in 96% (75%-100%) without any difference between functional and nonfunctional panNENs and without relevant side effects (mild adverse events, AEs 13.7%)[78-81].

The same conclusions were also confirmed by a further systematic review which included 14 studies with a total of 158 patients with solid pancreatic tumors[82]. However, even if the results of these studies are encouraging, especially for nonfunctioning panNENs and insulinomas < 2 cm, EUS-RFA is a recent technique and long-term data are thus lacking[82]. Larger studies with longer follow-up are needed to evaluate the long-term effectiveness of EUS-RFA. The specific setting of patients and the actual indication for the radiofrequency has not been standardized.

As concerned EUS-guided ethanol injection for small panNENs, this option has been proposed and studied for the treatment of patients with small panNENs not suitable for surgery or who refused surgical approach. Using pure ethanol or ethanol-lipiodol emulsion, the complete ablation rate has been reported to be ~50% up to 80% by performing more sessions[83].

In view of these results, a study protocol for a multicenter prospective study has been published[84]and the results will become available in due time.

Finally, possible future intriguing perspectives can be represented by the application, also in panNENs, of the novel techniques of locoregional delivery of drugs, such as LOcal Drug EluteR[LODER(TM)] which is a novel biodegradable polymeric matrix that shields drugs. panNENs may be considered as a possible future field of application of locoregional radiotherapy by using fiducial markers implantation, similarly to other pancreatic cancers.

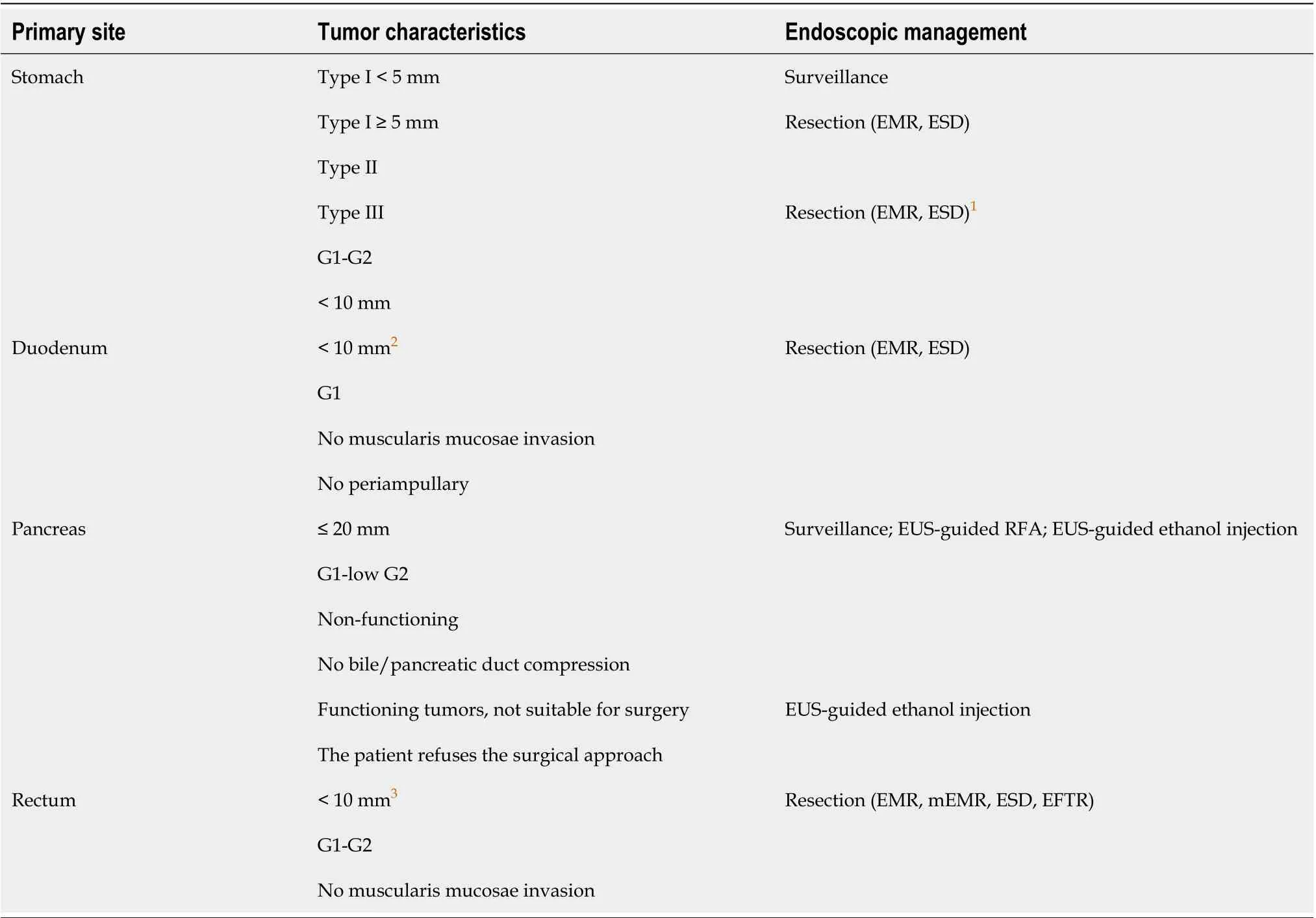

Table 1 Available endoscopic treatment options for gastro-entero-pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms

DlSCUSSlON

The incidence of GEP-NENs has hugely increased over the last decades mainly due to better disease knowledge and to an improvement in diagnostic techniques, including endoscopy. Standard axial endoscopy and EUS still play a pivotal role in several GEP-NENs. Upper GI endoscopy is essential for the detection and characterization of esophageal, gastric and duodenal NENs. EUS represents the diagnostic gold standard for panNENs and the technique of choice for the locoregional staging of gastric, duodenal and rectal NENs. Ileocolonoscopy allows the assessing and diagnosing of rectal,colonic and rarely distal ileal lesions. However, the diagnosis of sbNENs has been largely improved with the advent of CE and DBE, although data regarding the safety and efficacy of these techniques in the neuroendocrine setting are still scanty and their use is still limited in clinical practice. In terms of treatment, in selected localized GI-NENs with the absence of features associated with lymph node metastases, endoscopic therapy is generally an appropriate treatment with radical intent. In highly selected G1 or low G2 small neoplasms without radiological signs suspicious for malignancy EUSguided pancreatic locoregional ablative treatments, using either ethanol injection or radiofrequency ablation, have been proposed in recent studies with promising results in order to control symptoms or reduce tumor burden. Table 1 summarizes available endoscopic treatment options for GEP-NENs.

CONCLUSlON

In summary, endoscopy plays a key role for diagnosis and treatment of GEP-NENs. In selected localized GEP-NENs, endoscopic therapy is appropriate with radical intent. Advanced resection techniques aimed at increasing the rate of R0 resection should be reserved to high-volume referral centers. The multidisciplinary management remains the gold standard to offer the patient the best therapeutic approach.

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Rossi RE designed the research; Rossi RE, Elvevi A, Gallo C, Palermo A, and Massironi S performed the literature search and wrote the first draft of the paper; Rossi RE, Invernizzi P and Massironi S reviewed for important intellectual content; Rossi RE and Massironi S wrote the final version of the paper; all the authors approved it.

Conflict-of-interest statement:None.

PRlSMA 2009 Checklist statement:The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:Italy

ORClD number:Roberta Elisa Rossi 0000-0003-4208-4372; Alessandra Elvevi 0000-0001-9841-2051; Camilla Gallo 0000-

0002-7598-7220; Andrea Palermo 0000-0001-8057-9398; Pietro Invernizzi 0000-0003-3262-1998; Sara Massironi 0000-0003-

3214-8192.

S-Editor:Wu YXJ

L-Editor:Kerr C

P-Editor:Wu YXJ

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Involvement of Met receptor pathway in aggressive behavior of colorectal cancer cells induced by parathyroid hormone-related peptide

- Role of gadoxetic acid-enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma after locoregional treatment

- Clinical implications and mechanism of histopathological growth pattern in colorectal cancer liver metastases

- Bifidobacterium infantis regulates the programmed cell death 1 pathway and immune response in mice with inflammatory bowel disease

- Tumor-feeding artery diameter reduction is associated with improved short-term effect of hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus lenvatinib treatment

- Impact of sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors on liver steatosis/fibrosis/inflammation and redox balance in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease