Four-year experience with more than 1000 cases of total laparoscopic liver resection in a single center

2022-07-11XiangLanHaiLiZhangHuaZhangYuFuPengFeiLiuBoLiYongGangWei

Xiang Lan, Hai-Li Zhang, Hua Zhang, Yu-Fu Peng, Fei Liu, Bo Li, Yong-Gang Wei

Abstract

Key Words: Laparoscopic liver resection; Single-center experience; Learning curve; Liver

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) has become a safe approach for liver resection, following advances in surgical techniques, anesthesiology, and perioperative care. Since its first use was reported in 1996 by Azagraet al[1], LLR has evolved to become a primary choice of intervention for many patients with liver tumors[2-6]. Experience with laparoscopic procedures has allowed for the development of complex liver resection techniques using laparoscopy, including mesohepatectomy, caudate lobectomy, and even combined resection of several hepatic segments[7-9].

Total LLR has been performed since 2015 at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University. Although total LLR has been performed for a shorter period of time at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University compared to other centers, a large number of clinical patients in the western region of China have been treated with LLR at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University, conveying a rich experience in performing open liver resection to surgeons at the center. Over the past 4 years, LLR,including hemihepatectomy, mesohepatectomy, anatomical segmentectomy from segment I to VIII, and even the first case of laparoscopic donor hepatectomy in mainland China, has been performed successfully at the center[10]. The present study reviews the single center’s 4-year experience with LLR in more than 1000 patients and discusses its safety and feasibility, the learning curve for performing laparoscopic surgery, LLR technical innovations, and patient outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient characteristics

Patients who underwent LLR between January 2015 and December 2018 at the West China Hospital of Sichuan University were studied retrospectively. Inclusion criteria were as follows: patients who had undergone LLR due to liver disease; patients with hemangioma who met the following criteria: (1)Symptomatic hemangioma; (2) Increasing tumor size; (3) Heavy psychological burden and anxiety symptoms that affect daily life and require surgical treatment; (4) Tumor located in special segments (e.g., the caudate lobe or the porta hepatis) that are difficult to treat as tumor size increases; and (5)Unclear diagnosis in which the possibility of a malignant tumor cannot be completely ruled out; and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who met the following criteria: Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer 0-B stage HCC[11]; A3 stage with normal liver function after conservative treatment; and A4 or B stage with a tumor located in the same hemiliver. Exclusion criteria were as follows: patients who only received laparoscopic surgery without hepatectomy.

Patient data (age, sex, liver function before and after the operation, complications, hospital stay after the operation, operation time, hemorrhage, ascites, and perioperative mortality) were collected. All patients provided written informed consent for surgery, and this study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Figure 1 Hepatic inflow occlusion methods. A: Trocar position; B: Extracorporeal intermittent pringle maneuver; C: Anatomical continuous hemihepatic vascular inflow occlusion (CHVIO; intro-Glissonian methods); D and E: Extra-Glissonian CHVIO.

Surgical technique

Surgical procedures were described in our previous study[12]. A five-trocar approach was used at the tumor location (Figure 1A). Two hepatic inflow occlusion methods were adopted at the center[12].Intermittent pringle (IP): During the operation, hepatic inflow was blocked for 15 min and released for 5 min (Figure 1B) and continuous hemihepatic vascular inflow occlusion (CHVIO) (Figure 1C-E).

Histopathology

Liver capsule invasion and tumor location:Liver capsule invasion was determined by the histopathological report. In this study, “central tumor” was defined as a tumor within the main hepatic body,located in segments I/IV/V/VIII; otherwise, the tumor was considered a “marginal tumor”. If the tumor spanned across regions I/IV/V/VIII and another region, it was considered a “central tumor”.

Diagnosis of cirrhosis:Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by histological examination of hepatic tissues by two experienced pathologists. The histopathology diagnostic standard used to diagnose chronic hepatitis was previously described by Desmetet al[13]. G0-4/S1-3 was not considered liver cirrhosis,whereas G0-4/S4 was diagnosed as liver cirrhosis.

HCC differentiation:HCC differentiation was classified according to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System[14], with grade 1 being well differentiated, grade 2 moderately differentiated, and grade 3 poorly differentiated. At the center, pathological reports sometimes describe grade 1-2 or grade 2-3 HCC in a single patient. Patients with grades 1, 2 and 1-2 were allocated to the “well-to-moderately differentiated” group, and patients with grades 2-3 and 3 were allocated to the “poorly differentiated” group in this study.

Classification of complications:The Clavien–Dindo classification of surgical complications was adopted[15]. Grade I was regarded as the absence of complications, while Grades II-V were regarded as the presence of complications.

The learning curve

The learning curve of LLR was evaluated using the cumulative sum (CUSUM) method. The CUSUM procedure is a well-established method that detects data changes and monitors surgical performance. Inthis study, the operation time of each case was ordered chronologically (date of surgery). The formulation of the CUSUM was defined as: Where was an individual operation time, and was the mean of the overall operation time[16]. The learning curve is presented as a broken line graph according to the above formulation.

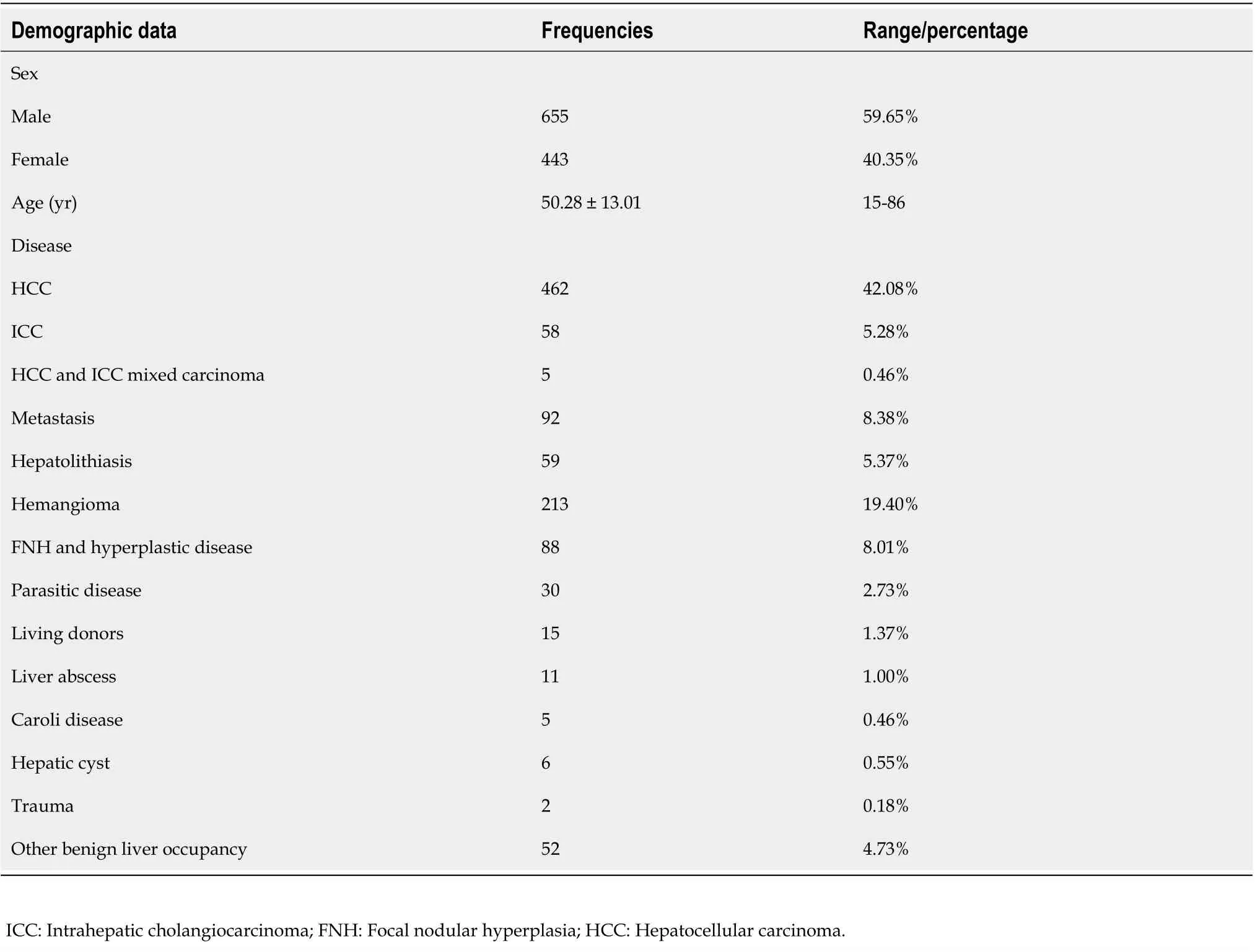

Table 1 The demographic data of all 1098 patients

Follow-up

Patients were followed up 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 and 36 mo postoperatively and assessed by computerized tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, liver function testing, and serum tumor marker measurement. All patients were followed until confirmation of death. If a patient lost contact during follow-up, the survival time was divided into the former interval of follow-up and was included in the censored data.

Statistical analysis

Measurement data between 2 comparative intervals were evaluated by independent-samplesttest.Pearson’s chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (when expected cell frequencies were less than 5) were used to determine significant differences in categorical parameters. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to perform survival analysis. Multiple regression analysis was used to assess risk factors determining the patient’s disease prognosis. APvalue < 0.05 was considered to represent a statistically significant difference.

RESULTS

Demographic data

A total of 1148 consecutive patients who received laparoscopic surgery (except laparoscopic cholecystectomy) between January 2015 and December 2018 were identified. Fifty patients did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining 1098 patients underwent LLR, and their demographic data were collected (Table 1).

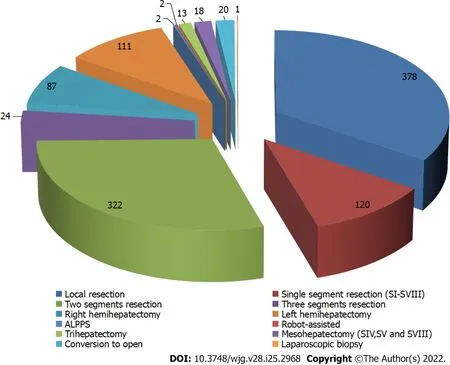

Figure 2 The details of different types of liver resection at the center. ALPPS: Associating liver partition and portal vein ligation for staged hepatectomy.

The average operation time was 216.95 ± 98.51 min (range, 31-650 min). The longest operation time was observed in LLR in which resection of a tumor in segments I, IV, V and VIII was combined with resection in the caudate lobe invading the middle hepatic vein[9]. The average blood loss was 242.51 ±143.23 mL (range, 5-4000 mL). The greatest blood loss, 4000 mL was observed in a patient who had liver paragonimiasis and that underwent conversion to open left hemihepatectomy with a splenectomy. A total of 22 patients (2.00%) underwent blood transfusion. The rate of conversion to open surgery was 1.82% (20/1098). With regard to methods of hepatic inflow occlusion, the IP maneuver was employed in 77.14% of patients (847/1098), and CHVIO was used in 21.58% of patients (237/1098). Local resection, 2 segmental resections and anatomical hepatectomy of a single segment represented the top 3 categories of LLR at the center (Figure 2).

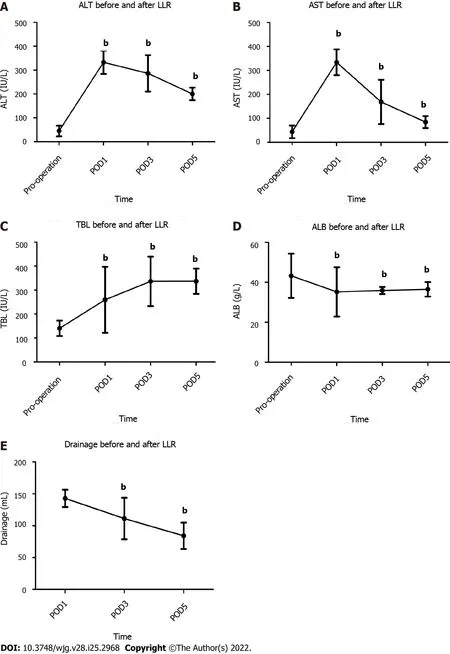

Compared with preoperative data, alanine transaminase and aspartate aminotransferase levels peaked at postoperative day (POD) 1 and then gradually decreased (P< 0.01, Figure 3A and B).However, the average total bilirubin level tended to increase postoperatively and peaked at POD 5 (P<0.01, Figure 3C). Albumin (ALB) levels and drainage decreased quickly following operation, and ALB levels were maintained at a lower level for a longer period of time (P< 0.01, Figure 3D and E).

The progression of surgical outcomes each year

Since the first LLR case in 2015, surgical procedures at the center have been continuously improved according to accumulated experiences. For example, the method of hepatic inflow occlusion was changed from CHVIO to IP, as the latter resulted in less blood loss and a clearer view of the operation site[12].

To further examine technique progression, surgical outcomes, including intraoperative data,mortality on POD 90, and surgical complications, were analyzed by year (Table 2). The inpatient time,postoperative inpatient time, operative time, postoperative liver function, mortality, complications, and drainage significantly decreased from year to year. Although some data (hospitalization expenses and blood loss) did not change significantly, the data trended toward decreasing over time. These results imply that surgeons at the center conquered the LLR learning curve, resulting in the LLR technique advancements.

The learning curves for different types of LLR

Considering that the surgical difficulty of different types of LLR is distinct, 3 representative LLR techniques were selected for investigation of their learning curves: local resection, anatomical resection,and right hemihepatectomy.

For local resection, there was one peak point observed in the 106thcase. Therefore, 2 phases were initially differentiated on the graph: Phase I, cases 1-106, and phase II, cases 107-373 (Figure 4A). For anatomical resection, 2 peak points were observed at the 44thand 74thcases. Therefore, 3 phases wereinitially differentiated on the graph: Phase I, cases 1-44; phase II, cases 45-74; and phase III, cases 75-120(Figure 4B). For right hemihepatectomy, there were 2 peak points observed at the 17thand 48thcases.Therefore, 3 phases were initially differentiated on the graph: Phase I, cases 1-17; phase II, cases 18-48;and phase III, cases 49-88 (Figure 4C).

Table 2 Main operation-related data for different years

These results indicate that the learning processes of anatomical resection and right hemihepatectomy were more complicated than the learning process of local resection and involved an initial period,increased competence in LLR, and then mastery and the challenging period.

HCC patient characteristics and disease prognosis

Among the 1098 patients enrolled in the study, 462 patients suffered from HCC, and 5 patients suffered from mixed carcinoma (Table 1). The details of all 467 patients with HCC-related disease are shown in Table 3.

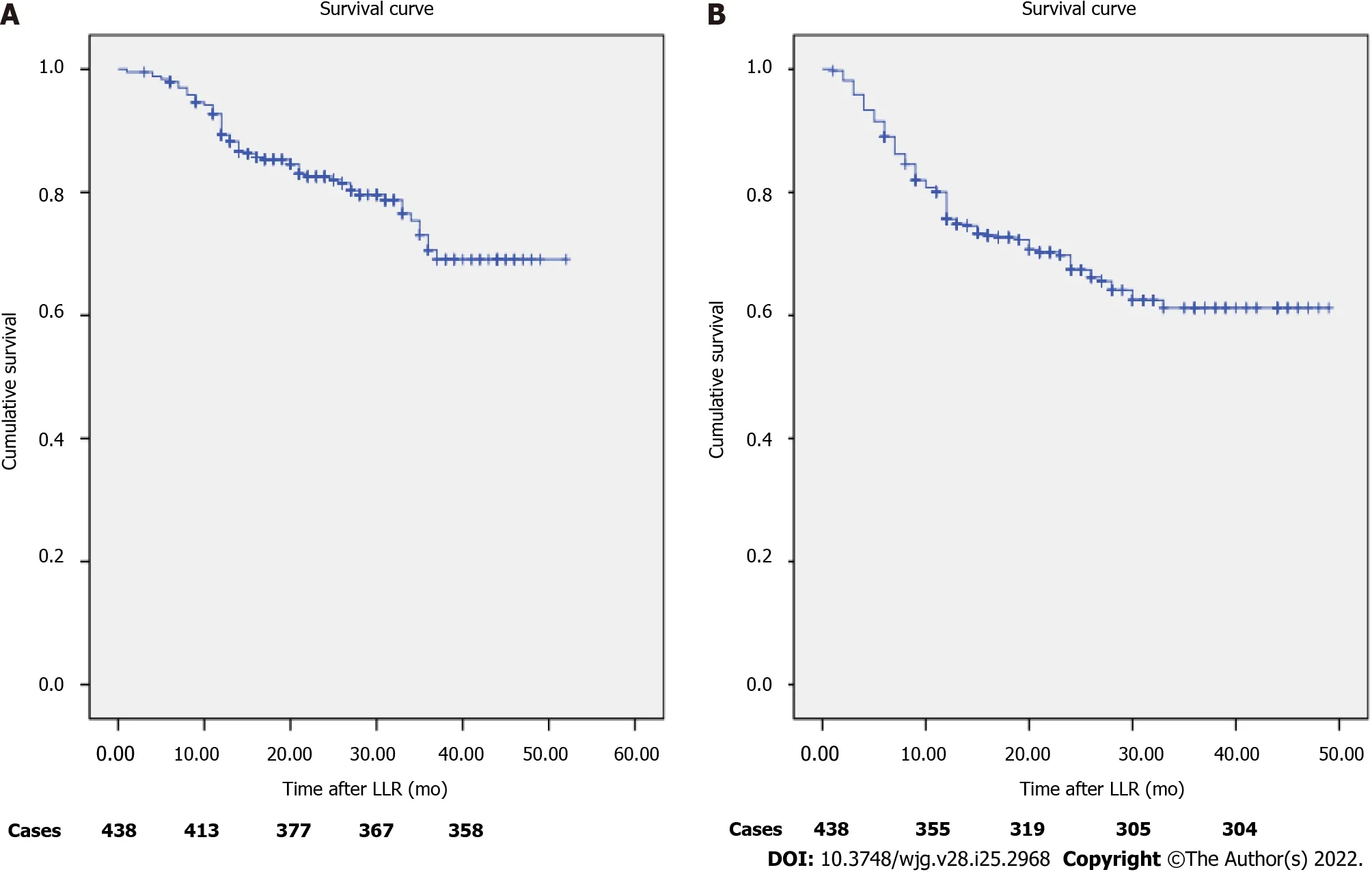

Follow-up data were obtained for 438 patients, and disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival(OS) were assessed. The 3-year DFS and OS rates were 69.4% and 81.9%, respectively. The 1-year DFS and OS rates were 76.3% and 89.7%, respectively (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Figure 3 Liver function and drainage trends in the perioperative period (bP < 0.01). A: Alanine transaminase before and after laparoscopic liver resection (LLR); B: Aspartate aminotransferase before and after LLR; C: Total bilirubin before and after LLR; D: Albumin before and after LLR; E: Drainage before and after LLR. ALT: Alanine transaminase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; LLR: Laparoscopic liver resection; ALB: Albumin; TBL: Total bilirubin; POD:Postoperative day.

The present study shows that LLR is a safe and efficient treatment for a variety of primary, secondary,and recurrent liver tumors and for benign diseases. LLR has several advantages, including minimal damage to the abdominal wall, faster postoperative recovery, and fewer patient complaints[17,18].Currently, LLR is widely performed in many liver surgery centers. The College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, was one of the first medical centers to perform LLR in China. They reported a 14-year,single-center experience with 365 cases and claimed that LLR has several advantages: lower economic burden, time saving, less blood loss, minimal harm, and improved safety[19]. Researchers also found that surgeons who use LLR must have extensive experience in performing open hepatectomy and that these surgeons will experience a learning curve when performing LLR. The need for a stepwise progression through the learning curve to minimize morbidity and mortality has been highlighted by many centers[20-22]. Furthermore, using laparoscopic surgery for major liver resections and liver resections for lesions adjacent to major vessels has been confirmed to be both feasible and safe[23-25].Previous researchers have claimed that the use of LLR for major liver resection has similar morbidity and mortality rates as open surgery. Moreover, tumor recurrence rates following LLR for lesions adjacent to major vessels was not increased[24]. Recent studies support the consensus that LLR is feasible, safe, and minimally invasive. Once surgeons progress through the learning curve, this procedure can offer benefits to patients. Hallset al[26] and Banet al[27] established a difficulty score model to predict intraoperative complications during LLR. Patient characteristics such as neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lesion type and size, classification of resection, and previous open liver resection were associated with a higher risk of surgery-related complications after LLR when compared to surgeryrelated complications after open liver resection. These findings may provide insight for surgeons when making treatment decisions to obtain better patient outcomes following LLR.

Figure 4 The learning curves for different types of laparoscopic liver resection. A: The learning curve for local resection; B: The learning curve for anatomical resection; C: The learning curve for right hemihepatectomy.

The large Chinese population, especially in Sichuan Province, allowed the center in the present study to accumulate over 1000 LLR cases in a 4-year period. These cases involved all types of LLR, including laparoscopic living donor resection. As reported, the increase in the volume of LLRs performed in 2009-2012vs2000-2008 may be partially attributed to the Louisville 2009 Consensus[28]. Therefore, approximately 22 out of the total of 160 cases were necessary to overcome the learning curve[22,29,30]. A decrease in blood loss during LLR was observed after a minimum of performing 50 cases[29]; and at least 25 cases were needed to master laparoscopic living donor resection[31]. At the center, 106 cases were needed to optimize local resectionviaLLR. However, for complex LLR, 2 peak points were observed in the learning curve. Repetitive training (an initial period, increased competence in LLR, and then mastery and the challenging period) was necessary for surgeons to master hemihepatectomy and anatomical resectionviaLLR. Furthermore, an increase in the conversion rate in 2016/2017 was noted.This time period corresponded to the second and third years of performing LLR at the center when surgeons were overcoming the second peak of the LLR learning curve and at which time there was a huge increase in the number of LLR cases requiring more complex surgeries. After the LLR technology was mastered, the conversion rate at the center decreased significantly in 2018.

Table 3 Characteristics of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and mixed carcinoma

Some studies have claimed that continuous hemi-hepatic vascular inflow occlusion is associated with similar outcomes as IP[32,33]. However, at the center in the present study, the IP method was adopted instead of hemihepatic vascular inflow occlusion once the LLR learning curve was overcome, as the IP method resulted in less blood loss than the hemihepatic vascular inflow occlusion method[12].Additionally, the intrahepatic Glissonian approach was adopted to replace the extra-Glissonian approach.

Figure 5 Survival rates of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. A: Overall survival rates; B: Disease-free survival rates. LLR: Laparoscopic liver resection.

The morbidity and mortality rates at the center are similar to those in other centers. One study reviewed 2804 patients who received LLR and found a cumulative mortality rate of 0.3% and a morbidity rate of 10.5%. Liver-specific complications included bile leaks (1.5%), transient liver ascites(1%), and abscesses (2%)[34]. At the center in the present study, in addition to observing these common complications, 4 patients who underwent right anterior lobectomy suffered from right posterior branch injury. One of these 4 patients suffered from liver failure and ultimately died. Due to this complication the LLR technique was improved so that a longer right anterior pedicle is now exposed prior to transection. Similarly, for patients who undergo right hemihepatectomy, the right anterior and posterior pedicle must be transected to prevent left pedicle injury. For patients who undergo left hemihepatectomy, the presence of ischemia in the right lobe following ligation of the left Glissonian sheath must be determined. The cause of death in the other 2 patients was refractory hypernatremia and ascites with liver failure. The most common postoperative complications at the center were pneumonia,hypohepatia, ascites, and bile leakage. Postoperative bleeding requiring a second operation was rare in these cases. Once the LLR learning curve was conquered and the LLR technique advanced and was optimized, postoperative complications significantly decreased from year to year.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, LLR may be performed safely for a variety of primary, secondary and recurrent liver tumors and for benign diseases. Once the learning curve is overcome, LLR can offer short-term benefits for patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research motivation

The present study reviews the 4-year experience of total LLR in a single center, which exceeded 1000 cases.

Research objectives

Summarize the past, in order to obtain better progress in this technology in the future.

Research methods

Patients who underwent LLR at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between January 2015 and December 2018 were identified. Surgical details in different years, categories of liver disease and prognosis of malignant liver tumors were evaluated. The learning curve for LLR was evaluated using the cumulative sum method. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to perform survival analysis.

Research results

Ultimately, 1098 patients were identified. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) was the most common disease that led to the need for LLR in our center (n= 462, 42.08%). The average operation time was 216.94 min ± 98.51 min. The conversion rate was 1.82% (20/1098). The complication rate was 9.20%(from grade II to V). The 1-year and 3-year overall survival rates of HCC patients were 89.7% and 81.9%,respectively. The learning curve was grouped into two phases for local resection (cases 1-106 and 107-373), three phases for anatomical segmentectomy (cases 1-44, 45-74 and 75-120) and three phases for hemi-hepatectomy (cases 1-17, 18-48 and 49-88).

Research conclusions

LLR may be considered a first-line surgical intervention for liver resection that can be performed safely for a variety of primary, secondary, and recurrent liver tumors and for benign diseases once technical competence is proficiently attained.

Research perspectives

It is a very promising surgical procedure that can give patients a faster recovery time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Chen YF (Department of Liver Surgery & Liver Transplantation Center, West China Hospital of Sichuan University) for the assistance of data collection.

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Lan X and Zhang HL contributed equally to this study and participated in the research design and preparation of the paper; Liu F, Zhang H and Zhang HL performed the statistical analysis; Li B revised this article and Wei YG performed the operation; all the authors contributed to this study.

Supported bySichuan Provincial Key Project-Science and Technology Project Plan, No. 2019yfs0372.

Institutional review board statement:All clinical investigations were in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Committee of Ethics in West China Hospital of Sichuan University.

Informed consent statement:Written informed consent for surgery was obtained from both patient and her family in this study.

Conflict-of-interest statement:All the authors have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Data sharing statement:No additional data are available.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Xiang Lan 0000-0002-5626-0106; Hai-Li Zhang 0000-0002-7291-7446; Hua Zhang 0000-0001-7277-1283;Yu-Fu Peng 0000-0002-0030-1714; Fei Liu 0000-0002-9650-1576; Bo Li 0000-0002-1411-3722; Yong-Gang Wei 0000-0002-0395-1691.

S-Editor:Yan JP

L-Editor:A

P-Editor:Yuan YY

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the impact of genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors in the offspring

- Role of transcribed ultraconserved regions in gastric cancer and therapeutic perspectives

- Multiple roles for cholinergic signaling in pancreatic diseases

- Early gastric cancer presenting as a typical submucosal tumor cured by endoscopic submucosal dissection:A case report

- Correction to “Aberrant methylation of secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine gene and its significance in gastric cancer”

- Mechanism and therapeutic strategy of hepatic TM6SF2-deficient non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases via in vivo and in vitro experiments