Green Transformation Of Palm Oil Industry

2022-06-23ByYuanYanan

By Yuan Yanan

The core problem with the palm oil industry is an acute contradiction between development and the environment

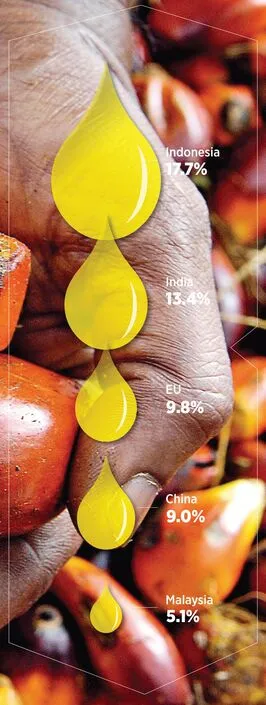

Five countries/regions consume more than half of global palm oil products (Getty Creative)

Palm oil may be the most controversial but ubiquitous ingredient in the world.

Globally, billions of people consume palm oil daily. Statistics by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations showed that global yield of palm oil in 2019 approached 74.6 million tons, around 36 percent of the world’s vegetable oil production. Indonesia, India, China, and the European Union are the primary consumers of palm oil.

“Palm oil is a widely used ingredient,” said Yu Xin, director of the sustainable food consumption and green supply chain program in the Beijing Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). “Almost half of the packaged goods in the grocery store contain it. Around 70 percent of palm oil is used for edible purposes including in cooking, food industry, instant noodles, and baking, and around 20 percent is used to manufacture daily-use chemicals. The rest is mainly used in biodiesel making and a tiny amount is used in the fodder industry.”

Statistics show that demand for palm oil products has been on the rise. From 2000 to 2015, per capita consumption worldwide doubled to 7.7 kilograms, and the figure is expected to triple by 2050.

The core problem with the palm oil industry is an acute contradiction between development and the environment. To producers, palm oil supports thousands of people’s livelihoods and represents a pillar of the country’s exports and a key source of revenue. But extensive planting of palm trees has resulted in deforestation and ecological degradation.

The increasing market demand makes green transformation of the palm oil industry a pressing issue.

Seeds of Strife

Originally native to West Africa, palm trees were brought to Southeast Asia in 1911 when Belgian merchants opened the first oil palm plantation on Sumatra of Indonesia. This ushered in an era of mass-producing palm oil in Southeast Asia. Today, Southeast Asia has emerged as the main oil palm growing area worldwide. Indonesia and Malaysia contribute around 85 percent of the world’s total palm oil yield.

A worker picks fruits from an oil palm tree at a plantation in North Sumatra, Indonesia, on March 15, 2022. (XINHUA)

The palm oil industry propelled economic development of palm growing countries, but also triggered serious environmental problems.

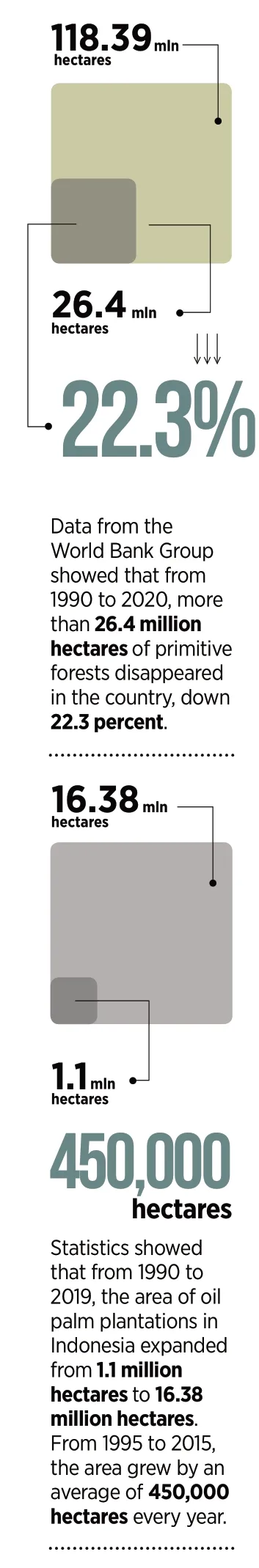

Since the 1990s, some businesses and individuals in Indonesia have burned down forests to give way for oil palm trees. Data from the World Bank Group showed that from 1990 to 2020, more than 26.4 million hectares of primitive forests disappeared in the country, down 22.3 percent. One of the main reasons was the expanding area for oil palm trees. Statistics showed that from 1990 to 2019, the area of oil palm plantations in Indonesia expanded from 1.1 million hectares to 16.38 million hectares. From 1995 to 2015, the area grew by an average of 450,000 hectares every year.

“Haphazard expansion of oil palm planting destroyed the rainforest and resulted in the loss of forest carbon sink and ecological functions of rainforest,” Yu said. “Burning banana trees caused greenhouse gas emissions and smog pollution. Peatland degradation destroyed forests’ carbon sink function. The destruction of the ecosystem further reduced local biodiversity and threatened the survival of local species like orangutans, Asian elephants, and rhinoceros.”

According to a 2020 report released by the United Nations Development Programme in China, replacing primeval and logging forests with oil palm trees would reduce biodiversity by 83 percent. Globally, the production of palm oil would threaten the survival of around 193 species, the report said.

However, there is no realistic alternative to palm oil despite the environmentally destructive nature of its production.

“Replacing palm oil with another oil is not a realistic option,” Yu said. “Palm oil has a very high yield, around 10 times higher than that of soybean oil, nine times higher than sunflower seed oil, and six times higher than colza oil. To get 5 million tons of oil, you need to plant 10 million hectares of soybeans. However, in the case of oil palms, only 1 million hectares are enough.”

WWF Germany Office estimated the costs and benefits of replacing palm oil with other vegetable oils. It was technically feasible but could not realize expected ecological goals because other vegetables need larger areas to grow, which, in turn, would lead to even more forest destruction. The result would be more greenhouse gas emissions and loss of biodiversity.

Thus, sustainable development of the palm oil industry has emerged as the most viable option.

A palm oil filling line in Malaysia. (ABDUL AZIZ BIN MOHAMED)

Green Transformation

Implementing sustainable standards is key to successful transformation of the palm oil industry.

“In simple terms, sustainable palm oil products are produced in a way that causes no harm to the environment and society,” said Yu. “Core environmental and social standards should be met, including zero harm to primeval forests and other natural habitats, no environmental pollution, and protection of wildlife and farmers’ interests.” Whether a bottle of palm oil is ideal or not doesn’t necessarily depend on the quality of the product per se.

A widely adopted practice is to grant sustainability certificates to stakeholders along the industrial chain. “In terms of production, Malaysia and Indonesia have introduced mandatory industrial standards, which, to some extent, raised public attention to agendas concerning plantations,” Yu said. “We suggest the mandatory standards be even stricter toward the goals of zero deforestation, zero peatland development, and zero community exploitation.”

Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) is a global not-for-profit organization established in 2004 with the objective of promoting the growth and use of sustainable palm oil products through global standards and multistakeholder governance.

“Our goal is to generate a positive impact on three key pillars for sustainable development:people, the Earth and development,” said Fang Lifeng, RSPO representative in China. According to him, RSPO certification for sustainable palm oil products sets standards and criteria for palm oil production, small farmers, and supply chains.

For example, RSPO-certified producers cannot fell trees or plant oil palm on peatland, and they need to safeguard workers’ rights and interests. Applicants must meet all key indicators to receive a certificate. RSPO members need to pass an annual audit and review every five years by a RSPO-recognized third party.

“To meet the standards, RSPO members will use less land to produce more palm oil and improve livelihoods while safeguarding human rights and labor rights and interests, preserving wildlife and biodiversity, and reducing destruction on the forest and land,” Fang said. By the end of 2020, 19 percent of global palm oil products had been certified by the RSPO. In China, merely 6 percent of palm oil consumed were certified by the RSPO, far short of the 10-percent goal for 2020.

Problems persist throughout the industrial chain. Palm oil producers on the upper reaches of the industrial chain need to meet standards of business transparency, natural resources and biodiversity preservation, and responsible land development. They also need to hire a third party auditor. The extra expenses to finish the procedures and improve production make things more difficult for small farmers. In Indonesia, the cost for small farmers to get certified can be as high as US$8 to US$12 per ton of oil palm, making it less appealing to adopt sustainable practices.

Oil palm dealers have found it difficult to distinguish supplies from certified plantations from the uncertified. This makes it necessary to extend the traceability chain to plantations. At the consumer end, many consumers are not willing to pay a premium ranging from 3 to 30 percent of the normal price. Sustainable palm oil products, therefore, are in a disadvantaged position in market competition. As a result, around half of the sustainable palm oil products worldwide are sold as regular products.

“In recent years, the proportion of RSPO-certified products has remained somewhere between 17 to 20 percent worldwide,” reported Yu Xin. “There has not been a significant increase. The transformation is still at an early stage.”

Sustainable Palm Oil in China

“China is the world’s second largest importer and third largest consumer of palm oil products, so it can play a key role in the transformation toward a sustainable palm oil industry,” Fang Lifeng said.

Many Chinese businesses have realized the importance of a sustainable palm oil industry. RSPO now has more than 270 members in China, and more keep joining. Members have pledged to scale up imports of sustainable palm oil products, but the current figure is still low.

In July 2018, the WWF, RSPO, and China Chamber of Commerce of Foodstuffs and Native Produce jointly launched the China Sustainable Palm Oil Alliance to encourage big firms to take action. Founding members include AarhusKarlshamn (AAK) China, Cargill China, HSBC, L’Oréal China, and Mars Wrigley Confectionery, among other multinationals.

China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation (COFCO) is China’s second largest importer of palm oil and a bellwether among centrally-administered enterprises promoting the import of sustainable palm oil products. Its subsidiaries have introduced procurement guidelines in this regard. In 2018, around 11 percent of COFCO’s palm oil imports were sustainable products.

Fang said businesses along the industrial chain and consumers alike still need to improve their awareness about sustainability. He is optimistic about the transformation of the palm oil industry in China. The country’s goals of carbon peaking by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 will inject vitality into national efforts towards green transformation and sustainable development. Fang predicted it would be conducive to ending deforestation and promoting imports of sustainable palm oil.

“China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment is formulating a national strategy for soft commodities to build green value chains, including for palm oil,” Fang said. As more and more businesses along the value chain for palm oil join the RSPO and purchase and consume certified products, China will play an important role in the global efforts to foster a green transformation of the palm oil industry.

Yu Xin shares Fang’s sentiments. She believes the sustainable palm oil industry has a favorable policy foundation and a promising future in China during the highquality development stage in the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-2025) because China is so determined to achieve the goals of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality.