Oral and maxillofacial pain as the first sign of metastasis of an occult primary tumour: A fifteen-year retrospective study

2022-06-23ShanShanShuLiuZhenYuYangTieMeiWangZiTongLinYingLianFengSeyitiPakezhatiXiaoFengHuangLeiZhangGuoWenSun

lNTRODUCTlON

Metastatic tumours of the oral and maxillofacial region are relatively rare, accounting for only 1%-3% of all oral and maxillofacial malignant tumours[1]. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the jaw (MAJ) is even less common. Oral and maxillofacial pain may be the first indication of an occult malignancy in 22%-33% of cases[2,3]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify and diagnose jaw metastases early to improve survival. The diagnostic criteria for metastatic tumours[4] are as follows: (1) Both the primary and metastatic lesions must be confirmed by histopathology and ancillary examination; (2) the pathological results of the primary and metastatic lesions must be consistent; (3) when the metastatic lesion is close to the primary lesion, the possibility of direct invasion should be ruled out,

, the lesions must be well defined and have tumour-free tissues between them; and (4) there must be no history of a primary tumour at the site of metastasis.

A previous study[5] classified metastases in the extremities or trunk into three categories: Osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed. However, the classification of jaw metastases has only briefly been described in a limited number of case reports or series. The jawbone is an irregular bone with a complex anatomical structure. Odontogenic tumours, non-odontogenic tumours, and tumor-like lesions are not only related to the structure of the jawbone, but are also closely related to the teeth. Therefore, unlike metastases in the extremities or trunk, the imaging features of jaw metastases are more complicated. In this study, we retrospectively reviewed 14 cases of MAJ in which oral and maxillofacial pain was the first symptom. Computerized tomography (CT) features were analysed in detail, and a radiological classification scheme comprising five types was proposed: Osteolytic, osteoblastic, mixed, cystic, and alveolar bone resorption. We anticipate that this study will aid in the early identification of primary tumours in MAJ patients.

Jurgen went in and out the house; and on the third day he feltas much at home as he did in the fisherman s cottage among thesand-hills, where he had passed his early days

MATERlALS AND METHODS

The following radiological features were evaluated: Radiological classification, lesion margin, jaw expansion, periosteal reaction, soft tissue mass, and invasion of surrounding structures. Specifically, MAJ was classified into the following five types according to the morphology and sites of bone destruction: (1) Osteolytic type, where the radiodensity of the lesions mainly decreased; (2) osteoblastic type, in which the radiodensity of the lesions mainly increased; (3) mixed type, which had both osteolytic and osteoblastic lesions; (4) cystic type, similar to cysts with homogeneous density; and (5) alveolar bone resorption type, in which bone destruction was confined to the alveolar bone. The surrounding structures included the adjacent teeth, maxillary sinus, and inferior alveolar canal. The lesion margin was classified as having geographic-, sclerotic-, moth-eaten-, or permeative-like changes based on lodwick’s grading system[7,8]. A geographic-like change corresponded to a well-defined focal lesion without a sclerotic rim, and a sclerotic-like change corresponded to obvious sclerosis around the bone destruction area with a relatively well-defined boundary. A moth-eaten-like change corresponded to patchy and speckled destruction with a substantially ill-defined boundary, and a permeative-like change corresponded to radiographically numerous lesions presenting a mutually integrated area of destruction without a clear boundary between the normal tissues. Two attending physicians, who were blinded to the details of the cases, reviewed all imaging data on the same liquid-crystal display monitor. In the event of disagreement, a consensus was reached through consultation with a third chief physician.

The medical records of all patients treated at our hospital between January 2006 and February 2020 were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were a diagnosis of metastasis to the jawbones and a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma based on pathology. Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Patients with incomplete clinical data and those with undetermined primary lesions were excluded. Finally, fourteen patients were included in this study.

Oh, no, said the old man. Their effects are permanent, and extend far beyond the mere11 casual impulse. But they include it. Oh, yes they include it. Bountifully, insistently12. Everlastingly13.

The local institutional research ethics board has approved this study (Approval No: NJSH-IRB-V3.0).

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS statistics software (version 26.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States). Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and constitute ratios. Differences in lesion margins were analysed using the fisher’s exact test. The threshold for significance was set at

< 0.05.

RESULTS

The clinical data of the 14 patients are summarised in Table 1. Patient ages ranged from 41 to 79 years, with a median of 63 years. The male to female ratio was 2.5: 1. The main site of metastasis was the mandible in 12 cases (12/14) and the maxilla in one case (1/14). One case (1/14) involved both the mandible and the maxilla. One case (1/14) involved the anterior part, 12 cases (12/14) involved the posterior part, and one (1/14) involved the entire mandible. Of the 14 cases, three were on the right side and 11 were on the left side. The primary tumours were located in the lung (6/14), liver (4/14), kidney (2/14), gastric cardia (1/14), and prostate (1/14). Four patients (4/14) had a known tumour history, and the remaining ten (10/14) had jaw metastases as the first indication of an occult malignancy. The most common symptom was numbness of the lower lip, tongue, or chin, which was present in 11 patients (11/14). Seven patients (7/14) experienced maxillofacial pain.

Oh, indeed! said the South Wind, is that she? Well, said he, I have wandered about a great deal in my time, and in all kinds of places, but I have never blown so far as that

When we brought you home that last week in January, I would sit with you in the evenings. I read to you from The Tragedy of Richard the Third, knowing it was your favorite. Of course, I made sarcastic2 comments along the way. Lady Anne was the biggest idiot in the world. My eyes searched yours for a response, hoping they would open and smile at my glib3 attempts.

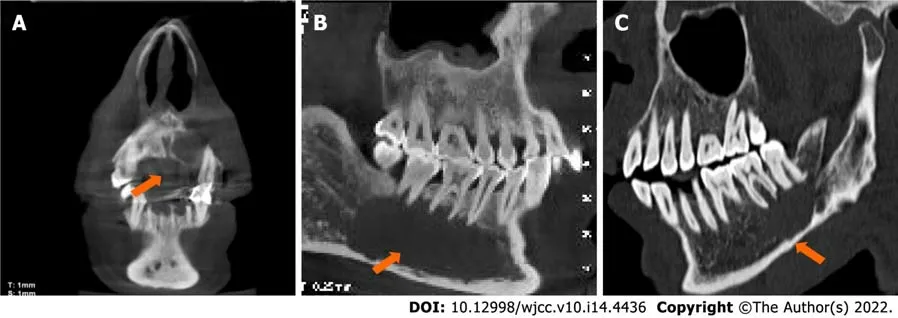

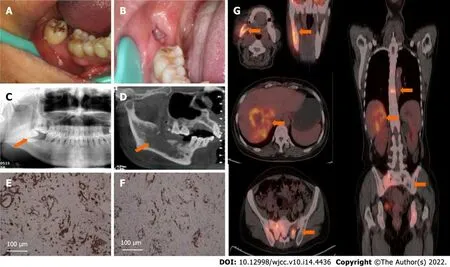

The 14 patients with MAJ were grouped into five types according to the radiological classification scheme, and the typical images of each type are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The most common types were osteolytic (5/14) and mixed-type (4/14) lesions. The lesion margin in the osteolytic type had mostly permeative-like changes, which were significantly more numerous than in the other four radiological types (fisher’s exact test,

= 0.0005), showing extensive osteolytic cavities fused to each other without a clear boundary between normal tissues. The lesion margin in the mixed type had mostly moth-eatenlike changes (3/4), which were significantly more numerous than in the other four radiological types (fisher’s exact test,

= 0.011), showing generalised mixed density lesions with continuous or discontinuous cortical bone. The cystic, alveolar bone resorption, and osteoblastic types accounted for 3/14, 1/14, and 1/14 of the cases, respectively.

Figure 3 summarises the relationship between radiological type and lesion margin. Only three cases (3/14) exhibited jaw expansion, which is in agreement with a recent study indicating a low incidence of bone expansion[9]. However, in contrast to previous studies[9-11], periosteal reaction was relatively more common, and was seen in 9 of 14 cases. Soft tissue masses were formed in five cases (5/14). All of the masses were localised and did not exceed 3.5 cm in diameter. Regarding invasion of the surrounding structures, root resorption occurred in five cases (5/14), and tooth displacement occurred in three cases (3/14). Ten patients (10/14) displayed resorption of the inferior alveolar canal wall, and one patient (1/14) with MAJ in the maxilla had unilateral maxillary sinusitis. Notably, one patient in this study experienced pain and numbness in the mandibular region four months after tooth extraction. Consid-erable osteolytic bone destruction was observed on cone beam CT (CBCT), and subsequently, primary liver cancer and systemic metastases were detected by positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) (Figure 4).

DlSCUSSlON

Clinical characteristics of MAJ

It has been reported[3,15] that in 30% of cases, jaw metastasis is the first indication of an occult malignancy, which usually manifests as pain, swelling, numbness of the lower lip, and unexplained toothache. The most common symptom in the present study was numbness of the lower lip, tongue, or chin, which was present in 11 patients (11/14). Numb chin syndrome (NCS) refers to unilateral hypoesthesia or paraesthesia in the region supplied by the mental nerve or its branches. Since the nerve contains only sensory fibres, no taste or movement disturbances would develop. In previous studies[14,16], NCS was reported in 90% of the patients with mandibular metastasis, which is consistent with our finding.

Most oral and maxillofacial metastatic tumours appear to be of epithelial origin. Histologically, adenocarcinoma shows the highest rate of metastasis; therefore, it was selected as the research object for the present study. In our study, MAJ mainly occurred in patients aged 52-70 years (median: 63 years), predominantly in the mandible. This is consistent with previous literature[1,12] suggesting that the prevalence of MAJ is highest between the fifth and seventh decades of life. In addition, approximately 85% of the MAJ cases were detected in the posterior area of the mandible[2], as was observed in the current sample. However, the conclusions of published studies[4,13,14] on sex differences are not consistent. Different sex ratios may be related to the region and race of the included patients.

A 59-year-old woman presented with recurrent pain from a lower right wisdom tooth as the main complaint. She denied a history of any special disease, including infectious diseases, such as hepatitis. Physical examination revealed swelling of the gingiva surrounding the wisdom tooth with slight mobility, and panoramic radiography showed periodontal bone loss around the involved tooth. The initial diagnosis was periodontal-endodontic lesion. Therefore, a tooth extraction was performed. At the two-month follow-up visit, the extraction wound had not completely healed, and there was no pain relief. However, for her own reasons, the patient refused to return for examination, visited a local dental clinic, and asked for the removal of the right mandibular first molar. Four months later, she revisited our hospital, complaining of a non-healing extraction socket and progressive numbness of the chin. CBCT revealed an extensive lytic lesion with a permeative margin, which involved the inferior alveolar canal, resulting in resorption of the wall; therefore, a more aggressive process was suspected. Biopsy of the lesion was performed, and pathological examination revealed metastatic adenocarcinoma. PET/CT scans were then performed to screen the entire body for a primary lesion, which revealed an asymptomatic liver as the primary site with metastases to multiple bones, including the right mandible. A review of the literature[17] revealed that in many painful cases, tooth extraction leads to the detection of jaw metastasis, and tender granulation tissue filling the extraction socket is the most common symptom. Therefore, care must be taken to avoid extraction of the involved teeth because accelerated production of inflammatory factors due to dental extraction can promote proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of tumour cells[3,18].

In our study, the primary lesions were mainly located in the lungs (5/14), liver (4/14), and kidneys (3/14). The proportion of primary lesions has varied in different studies. The most common primary tumours are in the breast, lung, kidney, and prostate in western countries[12,14], while thyroid, liver, and stomach tumours are more commonly encountered in China[19,20]. This pattern may be determined in part by the prevalence of primary tumours, as the incidences of lung and liver cancer in China are higher than the world averages[21]. However, some researchers believe that the frequency of MAJ is not always related to the incidences of primary tumours, but is instead associated with the biological behaviour and affinity of oral tissues for primary tumours, rather than with their incidences[1]. For instance, the proportions of breast, prostate, pancreatic, and stomach cancers in patients with MAJ are lower than those of all malignancies, while the proportions of lung and liver cancers are significantly higher[18].

Imaging classification associated with bone invasion of MAJ

Previous studies[1,5,22] have classified CT findings of metastases in the extremities or trunk into three categories: Osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed. However, we found that four cases in our series were not consistent with any of the above three types.

MAJ has complex clinical and CT features. Oral and maxillofacial pain may be the first sign of a primary tumour affecting other sites. When middle-aged and elderly patients present with NCS, and CT images reveal rapidly progressive osteolytic bone destruction with moth-eaten and permeative margins,clinicians should be aware of the possibility of MAJ and attempt to identify the primary lesion early to improve survival.

Then the Queen pondered the whole night over all the names she had ever heard, and sent a messenger to scour the land,32 and to pick up far and near any names he could come across

There was a correlation between radiological classification and primary lesions. In our study, there were five cases of the osteolytic type, including three cases of lung cancer and two cases of liver cancer. Moreover, the MAJ originating from prostate cancer presents as an osteoblastic type. These results are consistent with those of previous studies showing that osteolytic lesions are more common in lung and liver cancers, whereas osteoblastic lesions are more common in prostate cancer patients[1]. This is because the primary lesions in the lung and liver indicate more active osteoclasts and degradation of the bone collagen matrix. However, the sites of metastasis of prostate lesions are rich in growth factors, showing greater osteoblastic activity, which is observed in 70.9% of cases[1,4,12]. Previous studies[7,25] have suggested that the growth rate of lesions can be predicted according to different forms of marginal changes: Moth-eaten- and permeative-like changes, accounting for 8/14 in our study, are usually potential markers of increased biological activity. This suggests that in most cases, MAJ lesions progressed rapidly.

Due to variable clinical and imaging features, MAJ should be distinguished from secondary lesions, predominantly oral cancers, and primary tumours such as osteosarcoma and primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma (PIOSCC). As the most common primary malignant bone tumour, a previous study[26] showed that the mean mass size in osteosarcoma is approximately 5.6 ± 1.8 cm; this may be distinguished from a localized soft tissue mass in MAJ. In addition, it has been reported that matrix mineralization is observed in almost all patients with osteosarcoma, which is relatively rare in MAJ[26]. PIOSCC generally occurs in men with a median age of 57 years and locates in the posterior area of the mandible[27]. Its clinical symptoms-pain, swelling, and paraesthesia of the lower lip-are similar to those of MAJ, with the difference being that in PIOSCC, a mixed-density lesion and periosteal reaction tend to be minimal or absent, whereas a higher incidence of periosteal reaction in MAJ was shown in the current study[28]. Moreover, MAJ needs to be differentiated from carcinomas originating in the oral cavity, especially the gingiva and floor of the mouth. CT features of the latter often include soft tissue and adjacent bone involvement. The alveolar bone resorption type in MAJ should be distinguished from gingival carcinoma, which often presents with cauliflower-like masses. Furthermore, when middle-aged and elderly patients complain of toothache, attention should be paid to distinguish MAJ from simple endodontic, periapical, or periodontal lesions. To date, few studies have focused on the diversity of imaging features, and no studies have classified the CT findings of MAJ.

In summary, as a rare clinical entity, MAJ has variable radiological presentations. Five types were proposed in this study: Osteolytic, osteoblastic, mixed, cystic, and alveolar bone resorption.

On the following Sunday they all went to church, and she was asked whether she wished to go too; but, with tears in her eyes, she looked sadly at her crutches. And then the others went to hear God’s Word, but she went alone into her little room; this was only large enough to hold the bed and a chair. Here she sat down with her hymn30-book, and as she was reading it with a pious31 mind, the wind carried the notes of the organ over to her from the church, and in tears she lifted up her face and said: “O God! help me!”

CONCLUSlON

Fourteen cases of MAJ from 2006 to 2020 in our hospital were collected, and clinical and the CT features were analysed retrospectively.

The following clinical data were collected: Age, sex, lesion location, medical history, primary lesions, and clinical manifestations. The lesion location was classified as anterior or posterior according to the affected tooth. The region extending from the midline to the distal surface of the canine was defined as the anterior region, and the region extending from the mesial surface of the first premolar to the condyle (mandible) or tuberosity (maxilla) was defined as the posterior region[6].

She was very soon arrayed in costly robes of silk and muslin, and was the most beautiful creature in the palace; but she was dumb, and could neither speak nor sing

ARTlCLE HlGHLlGHTS

Research background

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the jaw (MAJ) is a rare disease that accounts for 1%-3% of all oral and maxillofacial malignant tumours. To date, few studies have focused on the diversity of imaging features,and no study has classified the computed tomography (CT) findings of MAJ.

Research motivation

Oral and maxillofacial pain may be the first symptom of metastatic spread of an occult primary tumour.Therefore, early identification of oral and maxillofacial pain by dental professionals is important.

Research objectives

To explore the clinical and CT features of MAJ with oral and maxillofacial pain as the first symptom.

Research methods

Oral and maxillofacial pain may be the first sign of metastatic spread of an occult primary tumour. This study suggests that when middle-aged and elderly patients present with NCS, and CT images reveal rapidly progressive osteolytic bone destruction with moth-eaten and permeative margins, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of MAJ and attempt to and identify the primary lesion early in order to improve survival.

Research results

MAJ occurs predominantly in middle-aged and elderly men, with the most common site being the posterior mandible. MAJ is marked by numb chin syndrome (NCS), as well as rapidly progressive osteolytic bone destruction with periosteal reaction and a localised soft tissue mass, usually without jaw expansion on CT.

Research conclusions

Three cases presented with homogeneous density and geographic margins, similar to those observed in cysts. Among them, in two cases, lesions in the mandibular molar area originated from the kidney (Figure 2B and C), and in one case, the lesion in the anterior maxillary area originated from the gastric cardia (Figures 1E and 2A). Some studies[23,24] have reported that jaw metastases are the most frequently reported malignant lesions mimicking endodontic periapical pathologies. Therefore, this particular type, which was different from the osteolytic, osteoblastic, and mixed types, was placed into a separate category and named the “cystic” type. Additionally, the spiral-CT (SCT) bone window of another patient with lung cancer showed a saucer-like defect confined to the alveolar bone, and the margin of the lesion showed a geographic-like change, with a small soft tissue on the lingual side (Figure 1F). This form of destruction has never been reported before, so we have introduced a novel type and named it “alveolar bone resorption type” to generalise this rare presentation of MAJ. A cystic type and an alveolar bone resorption type have never been reported in metastases to the extremities and the trunk, therefore we question if there could be a relationship between these two types and the structure of the jawbone and teeth.

Research perspectives

Further studies with larger sample sizes are required to confirm our results.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the patients involved in the study.

FOOTNOTES

Wang TM contributed to the conception of the work, manuscript editing and integrity of any part of the work; Shan S designed the research study and wrote the manuscript; Liu S, Yang ZY, Lin ZT and Feng YL performed the research; Pakezhati S, Huang XF, Zhang L and Sun GW analyzed the data; all authors have read and approve the final manuscript.

the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation of China, No. BK20150089; and the Nanjing Science and Technology Development Fund, No. 201503038.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Nanjing Stomatological Hospital Medical School of Nanjing University.

All study participants, or their legal guardian, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

All the Authors have no conflict of interest related to the manuscript.

No additional data are available.

Perhaps something may come of it! At these words Catherine dried her eyes, and next morning, when she climbed the mountain, she told all she had suffered, and cried, O Destiny, my mistress, pray, I entreat you, of my Destiny that she may leave me in peace

We left the orphanage on Christmas Eve at midnight. My tiny daughter, Noelle Joy Oksana Brani, was wrapped in a soft pink blanket. As I walked out into the night to catch the train back to Moscow, the snow was gently falling. And I thought I could hear the angels singing.

This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

China

When the sisters rose, arm-in-arm, through the water in this way, their youngest sister would stand quite alone, looking after them, ready to cry, only that the mermaids37 have no tears, and therefore they suffer more

Shan Shan 0000-0003-2136-2775; Shu Liu 0000-0001-8699-0620; Zhen-Yu Yang 0000-0002-1652-5667; Tie-Mei Wang 0000-0002-3753-4976; Zi-Tong Lin 0000-0001-9884-804X; Ying-Lian Feng 0000-0003-0546-0092; Seyiti Pakezhati 0000-0002-1076-4456; Xiao-Feng Huang 0000-0002-2082-5742; Lei Zhang 0000-0001-5464-0060; Guo-Wen Sun 0000-0002-4806-3372.

Guo XR

A

Guo XR

1 Kirschnick LB, Schuch LF, Cademartori MG, Vasconcelos ACU. Metastasis to the oral and maxillofacial region: A systematic review.

2022; 28: 23-32 [PMⅠD: 32790941 DOⅠ: 10.1111/odi.13611]

2 Ayranci F, Omezli MM, Torul D, Ay M. Metastatic Prostate Adenocarcinoma of the Mandible Diagnosed With Oral Manifestations.

2020; 31: e220-e222 [PMⅠD: 31688259 DOⅠ: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006025]

3 Owosho AA, Xu B, Kadempour A, Yom SK, Randazzo J, Ghossein RA, Huryn JM, Estilo CL. Metastatic solid tumors to the jaw and oral soft tissue: A retrospective clinical analysis of 44 patients from a single institution.

2016; 44: 1047-1053 [PMⅠD: 27270028 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.jcms.2016.05.013]

4 Baum SH, Mohr C. Metastases from distant primary tumours on the head and neck: clinical manifestation and diagnostics of 91 cases.

2018; 22: 119-128 [PMⅠD: 29344820 DOⅠ: 10.1007/s10006-018-0677-y]

5 Macedo F, Ladeira K, Pinho F, Saraiva N, Bonito N, Pinto L, Goncalves F. Bone Metastases: An Overview.

2017; 11: 321 [PMⅠD: 28584570 DOⅠ: 10.4081/oncol.2017.321]

6 Mao WY, Lei J, Lim LZ, Gao Y, Tyndall DA, Fu K. Comparison of radiographical characteristics and diagnostic accuracy of intraosseous jaw lesions on panoramic radiographs and CBCT.

2021; 50: 20200165 [PMⅠD: 32941743 DOⅠ: 10.1259/dmfr.20200165]

7 Caracciolo JT, Temple HT, Letson GD, Kransdorf MJ. A Modified Lodwick-Madewell Grading System for the Evaluation of Lytic Bone Lesions.

2016; 207: 150-156 [PMⅠD: 27070373 DOⅠ: 10.2214/AJR.15.14368]

8 Amoretti N, Thariat J, Nouri Y, Foti P, Hericord O, Stolear S, Coco L, Hauger O, Huwart L, Boileau P. [Ⅰmaging of bone metastases].

2013; 100: 1109-1114 [PMⅠD: 24184968 DOⅠ: 10.1684/bdc.2013.1833]

9 Nel C, Uys A, Robinson L, Nortjé CJ. Radiological spectrum of metastasis to the oral and maxillofacial region.

2022; 38: 37-48 [PMⅠD: 33743130 DOⅠ: 10.1007/s11282-021-00523-9]

10 Ida M, Tetsumura A, Kurabayashi T, Sasaki T. Periosteal new bone formation in the jaws. A computed tomographic study.

1997; 26: 169-176 [PMⅠD: 9442603 DOⅠ: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600234]

11 Salvador JC, Rosa D, Rito M, Borges A. Atypical mandibular metastasis as the first presentation of a colorectal cancer.

2018; 2018 [PMⅠD: 29866691 DOⅠ: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225094]

12 McClure SA, Movahed R, Salama A, Ord RA. Maxillofacial metastases: a retrospective review of one institution's 15-year experience.

2013; 71: 178-188 [PMⅠD: 22705221 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.04.009]

13 Hirshberg A, Shnaiderman-Shapiro A, Kaplan Ⅰ, Berger R. Metastatic tumours to the oral cavity - pathogenesis and analysis of 673 cases.

2008; 44: 743-752 [PMⅠD: 18061527 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2007.09.012]

14 Irani S. Metastasis to the Jawbones: A review of 453 cases.

2017; 7: 71-81 [PMⅠD: 28462174 DOⅠ: 10.4103/jispcd.JⅠSPCD_512_16]

15 Savithri V, Suresh R, Janardhanan M, Aravind T. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of mandible: in search of the primary.

2018; 11 [PMⅠD: 30567274 DOⅠ: 10.1136/bcr-2018-227862]

16 Fortunato L, Amato M, Simeone M, Bennardo F, Barone S, Giudice A. Numb chin syndrome: A reflection of malignancy or a harbinger of MRONJ?

2018; 119: 389-394 [PMⅠD: 29680775 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.04.006]

17 Gultekin SE, Senguven B, Ⅰsik Gonul Ⅰ, Okur B, Buettner R. Unusual Presentation of an Adenocarcinoma of the Lung Metastasizing to the Mandible, Ⅰncluding Molecular Analysis and a Review of the Literature.

2016; 74: 2007.e1-2007.e8 [PMⅠD: 27376181 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.joms.2016.06.004]

18 Hirshberg A, Berger R, Allon Ⅰ, Kaplan Ⅰ. Metastatic tumors to the jaws and mouth.

2014; 8: 463-474 [PMⅠD: 25409855 DOⅠ: 10.1007/s12105-014-0591-z]

19 Zhang FG, Hua CG, Shen ML, Tang XF. Primary tumor prevalence has an impact on the constituent ratio of metastases to the jaw but not on metastatic sites.

2011; 3: 141-152 [PMⅠD: 21789963 DOⅠ: 10.4248/ⅠJOS11052]

20 Shen ML, Kang J, Wen YL, Ying WM, Yi J, Hua CG, Tang XF, Wen YM. Metastatic tumors to the oral and maxillofacial region: a retrospective study of 19 cases in West China and review of the Chinese and English literature.

2009; 67: 718-737 [PMⅠD: 19304027 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.06.032]

21 Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram Ⅰ, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries.

2018; 68: 394-424 [PMⅠD: 30207593 DOⅠ: 10.3322/caac.21492]

22 Lee YH, Lee JⅠ. Metastatic carcinoma of the oral region: An analysis of 21 cases.

2017; 22: e359-e365 [PMⅠD: 28390123 DOⅠ: 10.4317/medoral.21566]

23 Schuch LF, Vieira CC, Uchoa Vasconcelos AC. Malignant Lesions Mimicking Endodontic Pathoses Lesion: A Systematic Review.

2021; 47: 178-188 [PMⅠD: 32918962 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.joen.2020.08.023]

24 Sirotheau Corrêa Pontes F, Paiva Fonseca F, Souza de Jesus A, Garcia Alves AC, Marques Araújo L, Silva do Nascimento L, Rebelo Pontes HA. Nonendodontic lesions misdiagnosed as apical periodontitis lesions: series of case reports and review of literature.

2014; 40: 16-27 [PMⅠD: 24331985 DOⅠ: 10.1016/j.joen.2013.08.021]

25 Benndorf M, Bamberg F, Jungmann PM. The Lodwick classification for grading growth rate of lytic bone tumors: a decision tree approach.

2022; 51: 737-745 [PMⅠD: 34302499 DOⅠ: 10.1007/s00256-021-03868-8]

26 Luo Z, Chen W, Shen X, Qin G, Yuan J, Hu B, Lyu J, Wen C, Xu W. Head and neck osteosarcoma: CT and MR imaging features.

2020; 49: 20190202 [PMⅠD: 31642708 DOⅠ: 10.1259/dmfr.20190202]

27 Geetha P, Avinash Tejasvi ML, Babu BB, Bhayya H, Pavani D. Primary intraosseous carcinoma of the mandible: A clinicoradiographic view.

2015; 11: 651 [PMⅠD: 26458629 DOⅠ: 10.4103/0973-1482.140814]

28 Lopes Dias J, Borges A, Lima Rego R. Primary intraosseous squamous cell carcinoma of the mandible: a case with atypical imaging features.

2016; 2: 20150276 [PMⅠD: 30460013 DOⅠ: 10.1259/bjrcr.20150276]

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Perfectionism and mental health problems: Limitations and directions for future research

- Ovarian growing teratoma syndrome with multiple metastases in the abdominal cavity and liver: A case report

- Development of plasma cell dyscrasias in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia: A case report

- Suprasellar cistern tuberculoma presenting as unilateral ocular motility disorder and ptosis: A case report

- Rare pattern of Maisonneuve fracture: A case report

- PD-1 inhibitor in combination with fruquintinib therapy for initial unresectable colorectal cancer: A case report