ANYTHING FLIES

2022-06-19TEXTBYSIYICHU褚司怡ILLUSTRATIONBYWANGSIQIPHOTOGRAPHSFROMLIUZHIJIANGANDVCG

TEXT BY SIYI CHU (褚司怡) ILLUSTRATION BY WANG SIQI PHOTOGRAPHS FROM LIU ZHIJIANG AND VCG

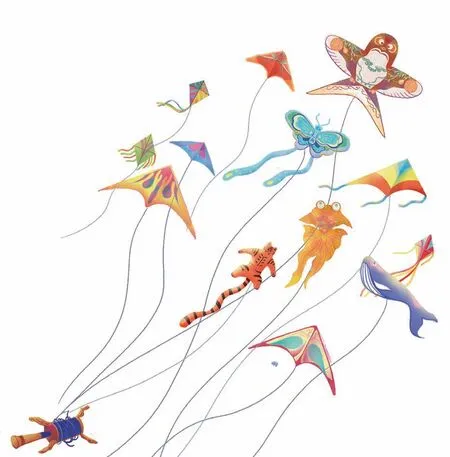

Backed by international competitions, a 2 billion yuan industry, and complex tricks and designs, kiting in China is no child’s play

风筝,不只是娱乐休闲

The blue-and-white space craft bearing the red five-star flag steadily docks at the space station as spectators on the ground cheer, waiting for the astronauts to eventually come out for a walk. But this wasn’t the scene from October 2021, when China’s Shenzhou-13 mission reached the Tiangong Space Station—instead, it took place on April 17, 2022, a few meters above an empty field in Weifang, Shandong province, with a spacecraft and space station constructed from bamboo and carbon fiber rods, wrapped in synthetic fiber, and completed with a miniature astronaut made of an ultralight moldable foam.

The Shenzhou-13 kite, which is eight meters long with a tail of 150 meters, took a core team of 11 artisans four iterations of design and two intensive months to build. “But it only took us one go to fly it successfully,” boasts Liu Zhijiang, a traditional kite craftsman and the mastermind behind this project, speaking with TWOC over the phone from Weifang, a city believed to be the birthplace of kites. The kite was modeled after the traditional local “dragon-head centipede-tail” kite style, while the “astronaut” was modeled after Liu himself and operated by a remote-controlled electric motor.

If it weren’t for a surge in local Covid-19 cases, this space kite’s “launch” would have also marked the beginning of the now-postponed 39th edition of the Weifang International Kite Festival, an annual fanfare that features various kite flying events and competitions, attracting tens of thousands of kite fliers and spectators from around China (and around the world before the pandemic) and choking off nearby car traffic.

The space station might be state-ofthe-art, but it is hardly the most bizarre kite that has graced Weifang’s skies. Giant meters-long nylon whales and octopuses are just run-of-the-mill, next to a life-size boat decorated in rainbow colors and a name tag that says “Noah’s Ark,” and a record-breaking 7,700-meter dragon kite that took 50people to get off the ground at the 2021 festival, according to the Weifang Evening News.

Liu Zhijiang puts together the space station kite in his studio

The history of kites in China is commonly traced back to philosopher Mozi (墨子) from the Warring States period (475 –221 BCE), who allegedly spent three years crafting amuyuan(木鸢), an eagle-shaped flying machine out of wood, but failed to make it fly. In the Sui dynasty (581 –618), armies used kites to send messages, and by the Song dynasty (960 –1279), there were records of people going out to the suburbs to fly kites for fun around the traditional Qingming season in spring.

Now more than 2,000 years after Mozi, kite festivals like Weifang’s are popping up all over China, while parks are still dotted by young and old alike with strings in hand, eyes squinted, and heads tilted upward. Kite culture seems to be alive and well, and becoming increasingly high-stakes through international competitions and commercial opportunities, while its devotees try to navigate between heritage and trend.

Even before 65-year-old Liu Aiguo retired as a police officer in Jinan, whenever he heard about a kite competition somewhere, he would gather a group of local hobbyists and hop on a Friday night train. “We competed all Saturday and Sunday, and then took another train to come back to Jinan—work was important after all,” Liu, who still frequents these competitions, reminisces to TWOC over the phone.

The “astronaut” rises out of the space station kite holding China’s national flag

Four versions of the space station kite were made before it was ready to fly

Stunt kite enthusiasts take their quad-line kites out for a spin in September 2020, during the delayed 37th Weifang International Kite Festival

Liu Aiguo and his teammates fly all kinds of hardware at these competitions: two-string or fourstring stunt kites that can perform precise movements, giant soft kites, and traditional bamboo-frame kites. Each category has its own rules and standards. Kite fighting uses stunt kites that cut other kites’ lines; kite ballet sees kites flown in complex 2-to-5-minute choreographies; whereas large soft kites and traditional kites are evaluated based on their styles, aerial presentation, or innovation. Teams that sign up are often required to enter every category for best results, Liu explains.

Since he became hooked on this activity in his 40s, Liu Aiguo’s hobby has taken him to kite festivals across China—from Tianjin in the north, to Wuzhou city of Guangxi in the southwest, plus Yangjiang and Zhuhai in Guangdong province in the southeast—and even to Malaysia. “We’re not like the old men and kids playing with kites you see around. We’re professionals,” Liu brags.

In China, professional kiting is indeed more than child’s play. In its 2021 annual budget, the Social Sport Guidance Center under the General Administration of Sport of China (GAS) listed kiting as a sport program it supports and promotes, alongside others like rollerblading, dragon boat racing, pigeon racing, tug-of-war, and darts.

The Chinese Kite Association (CKA), a national organization recognized by GAS, was set up in 1987 to connect kite-fliers across China, provide guidance to kiting sport events, and advance the cultural heritage of kites. In May 2002, the CKA finalized rules for kite competitions, which takes both craftsmanship of the kite and flying skills of the flier or team of fliers into consideration. Now the organization continues to train kiting referees and sends them to judge events around the country.

Although kiting may look relaxing, safety concerns have also prompted the CKA to supervise and regulate the sport. “Thin kite strings can cut your throat,” Hou Qiuling, secretarygeneral of the CKA, declares to TWOC solemnly, “and thick ones can break your leg on a very windy day.” In 2019, a kite enthusiast in Jiangsu province got his 5-meter-long homemade kite stuck in high-voltage power lines after strong wind broke its string. Firefighters had to break the kite, which took the owners 10 years to make, to remove it and ensure the safety of the power lines. “If he had reached out to us or a local kite association, we would’ve advised him on what kind of string to use in wind conditions like this,” Hou says with regret.

While the CKA works with more than 50 provincial or city-level kite associations, Hou finds it hard to estimate the scale of enthusiasm for kites in China, as many kite fliers spontaneously self-organize into unconnected local clubs. Liu Aiguo, for example, has founded “Patriotic Eagle,” a social kiting club in Jinan that now runs WeChat groups consisting of more than 500 local fliers. The youngest members are in their 20s while the oldest is over 100, and still rides his electric scooter to fly kites on outdoor plazas every day.

A form of traditional kite now rarely in production, recovered by Liu Zhijiang

A kite skeleton made of 180 pieces of bamboo strips, which took Liu Zhijiang 60 days to finish

“It’s good for your heart, agility, and brain,” claims Liu Aiguo. Among all the kites he has flown,panying(盘鹰, “hovering eagle”), an eagle-shaped traditional kite that can mimic the smooth gliding and hovering of the predator, even in windless conditions or indoors, has become Liu’s favorite. “It’s quite an exercise,” he explains to TWOC, passionately describing how the flier must have sharp eyes, nimble footwork, and whole-body coordination to maneuver the kite in a sophisticated way.

In China, from Liu’s experience, “doctors might recommend flying kites if you go to them for neck or shoulder pain.” The term “kite therapy (风筝疗法)” has been circulating on some state media outlets, as recommended intervention for conditions related to mental health and eyesight. These sources often citeContinued Encyclopedia(《续博物志》), completed by the writer Li Shi (李石) of the Song dynasty, which applauded kite flying as “making children look up with mouths open, which releases inner heat.”

Traditionally, kites also functioned as a form of communication and well-wishing. Hanging on the wall in the CKA’s Beijing office, opposite Hou’s desk, is a plank-shaped kite decorated with delicate paintings and bamboo whistles—abanyao(板鹞, literally “plank eagle”) originating from Nantong in China’s eastern Jiangsu province. “We nickname it ‘aerial symphony,’” Hou says, noting it could serve as a beacon in ancient times.

Next wall over, next to apanyingand a kite shaped like a Beijing opera mask, Hou points to a blue and white Beijing-styled swallow kite with a cat, a butterfly, and peonies illustrated on each side of its body. She explains it carries the wish for wealth and elegance for elders, asmaodie(耄耋), a term for octogenarians, is pronounced like a combination of “cat” and “butterfly.”

Kites can also send messages internationally. Wang Yongxun, a Weifang businessman and kitemaker, has traveled to more than 40 countries to share China’s kite culture, often offering demonstrations of the kite-making process, at the invitation of various branches of Chinese diplomatic missions abroad. “Ministry of Agriculture, because I am a farmer-entrepreneur,” Wang counts them off over the phone, “Ministry of Commerce, as kites are consumer goods…” The list goes on to include the Communist Party’s Publicity Department, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and the GAS.

Foreign kites made of more durable materials were introduced to China in the 1990s, opening up new possibilities to create larger spectacles at lower costs—such as the octopus and large fish kites made of soft nylon at festivals—with more commercial uses. “If you sell houses, we can make a big flying building [for your advertisement]; If you sell cars, we can make cars,” Wang says. “Any need the client has, we can make it [into kites].”

Weifang is now building a modern kite culture and industry. In 1984, Weifang hosted its first-ever international kite festival, inviting participants from 11 countries and regions including the US, UK, Japan, the Netherlands, and Australia.

The two decades that followed were “the heyday of traditional kites…It was a society-wide movement,” Liu Zhijiang, the space-station kite-maker, believes. At that time, the Weifang government assigned every company and public institution, even ones that had nothing to do with kites, a “kitemaking quota” specifying the number of kites each entity had to produce and enter into the kite festival in a given year, according to Liu. He thinks this led to the emergence of a wave of excellent kite-makers whose craft might have been otherwise buried in their alternative careers.

Young kite-fliers at the Fourth Weifang International Festival in 1987

China Tourism News, a state media outlet, reported in 2020 that there were more than 300 kite related businesses in Weifang, generating an annual revenue of more than 2 billion yuan. State broadcaster CGTN claims that Weifang products make up 85 percent of the domestic kite market and 65 percent of the global market. “In Weifang, even the flour we eat is ‘Kite Brand,’” Li Naizeng, a local amateur kite enthusiast, tells TWOC.

Liu Zhijiang, however, is concerned that rapid commercialization is pushing traditional kites into a forgotten corner. Traditional kites, like the type Liu’s space station is based on, often feature complicated bamboo structures and exquisitely painted surfaces. Compared to their modern counterparts such as the nylon kites with simple structures or stunt kites, traditional ones take longer to make, cost more, and are more difficult to transport or fly, making them less suitable for mass production or as flying advertisements.

Others like Wang, who has turned kite-making into a business that brings in millions every year, believe commercialization is necessary to keep traditions alive. Kite-flying is often seasonal, peaking in spring time, when the wind speed is just right for kite flying—Wang says between 3 and 8 meters per second is ideal—and the temperature pleasant. But in the off-seasons, manufacturers struggle to retain craftspeople, making it hard to maintain production quality, as “it takes months and years to become good at making kites,” Wang says.

The instinct to survive or to turn profit, Liu Zhijiang worries, could dilute the craftsmanship and heritage. In spring 2021, the popular mobile gameHonor of Kingscollaborated with a Weifang kite maker to release a kite themed around the game, both as a gadget in the game, and as a reallife souvenir, claiming to effectively promote the culture of Weifang kites. However, Liu points out that the style of the swallow-shaped kite is actually of the Beijing school, and not local to Weifang.

Hou echoes the worry, “Ask anyone, adult or child, they all know about kites. But the culture and origins? Few know.” The CKA is now pivoting to focus less on sport competitions and more on cultural preservation, hoping to see regional kite traditions blossom beyond Weifang and all over China. Hou plans to collaborate with schools around the country, introducing special events, textbooks, and even online courses for students.

“When I was little, we used to fly kites as soon as we got out of school, running around all over the place,” Hou laments that such joy is taken away from children nowadays by heavy school work and environmental changes. “We want to rebuild their interest in this culture…from as early as kindergarten.”

Kites depicting all seven brothers from China’s famous cartoon, Calabash Brothers, plus their grandpa, took to the sky above Weifang in September 2020