Translating through Intersemiotic Translation Models:A Case Study of Ang Lee’sVishnu Image in Life of Pi*

2022-06-14ZHANGHaoxuanDurham

ZHANG Haoxuan Durham

Abstract:Though Roman Jakobson’s concept of intersemiotic translation en‐ables film to be discussed through the prism oftranslation studies,the binary verbumcentred paradigm of verbal to non-verbal transmission often neglects the non-verbal prior materials of film.To remedy this deficiency,these non-verbal materials will be rigorously investigated under the viewpoint of intersemiotic translation models.A multilevel system of intersemiotic translation models is proposed.This system con‐sists of a hierarchy of two levels:culture and semiotics.In this system,each interse‐miotic translation model is considered as a result of a cross-level combination that re‐lates to a specific type of media system from a specific cultural system,representing a lensthrough which acultureis“looked at”(Chow 1995).Itispostulated thatfilmmak‐ers translate by employing intersemiotic translation models,through which they me‐diate their intersemiotic translations across cultures.This paper interrogates film‐makers’employment of intersemiotic translation models through a case study ofAng Lee’s Vishnu image in his film Life of Pi.How Lee manifests such an image through the employment of intersemiotic translation models is discussed and illustrated with reference to the proposed system.

Keywords:Intersemiotic Translation Models;culture;system;AngLee;Life of Pi

Roman Jakobson’s definition of intersemiotic translation as“an inter‐pretation of verbal signs by means of signs of non-verbal sign systems”has made transduction in other non-linguistic disciplines a real possibility.To this end,complex polysemiotic communication between cultures can be formally addressed within the area of translation studies.Film can also be formally studied as a translational phenomenon.Though this concept enables a powerful tribute to the ongoing broad move away from words to images,it still falls under the linguistic-centred binarism that intersemiotic translation refers to as the verbal to non-verbal transmission process.Such an assertion,while providing prospects in studying the audio-visual,also limits researchers from getting a comprehensive overview of the complexity of the intersemiotic.In studying intersemiotic translation in the Jakobsonian sense,one must leave undiscussed the non-verbal prior materials of these audio-visual texts.If such a linguistic biasis to be radically broken,these non-verbal prior materials are the key to understanding the distinction between the verbal and non-verbal,as well as how one communicates through appropriating these non-verbal patterns;these elements are of central importance when considering the essential question:howdo intersemiotic translators translate andmediate between cultures?To answer this ques‐tion,these non-verbal patterns will be considered from the perspective of intersemiotic translation models.A system of intersemiotic translation models will be proposed,using a case study of Ang Lee’s employment of theVishnu landscape inasanexample.

Intersemiotic Translation Models

“Intersemiotic Translation Models”refer to the non-verbal priormaterials of film.The sematerials may support the translators in completing their intersemiotic translation projects,by provid‐ing pre-existing audio-visual patterns for the finalization process of an intersemiotic translation by means of which a screenplay is audio-visualized through film language.These patterns comprise the“models and conventions”which Patrick Cattrysse identified as governing audio-visual aspects such as“directing,staging,acting,setting,costume,lighting,photography,pictorial representa‐tion,music,etc.”If these materials,as semantic models,are imitated,reworked or mediated,they may inform or influence the translators’audio-visual solutions and eventually determine the audio-visual quality of the intersemiotic translation.Accordingly,these materials assist the film‐maker’s decision-making process by bringing in certain audio-visual components to“flesh out”the information in the script.

This concept has been recognized and theoretically approached by previous researchers who have been credited with terms such as“interpretant”and“repertoire.”The former descriptor,bor‐rowed from Charles S.Peirce’s semiotic trichotomy,emphasizes the intermediary position offilm’s audio-visual prior materials between the start text(ST)and the target text(TT).The latter,bor‐rowed from Even-Zohar’s systemic scheme,refers to the aggregation of all these audio-visual pri‐ormaterialsasatranslator’stoolkit.Neitherterm,however,describesthefunctionalnatureofindi‐vidual audio-visual prior material.“Interpretant”does not fully involve the user of the audio-visual prior materials,and can only be understood within a specific context along with a sign and an ob‐ject.“Repertoire”is recognized as referring to the full range of the filmmaker/translator’s tool kit,but is a general term that describes a cluster of tool kits without specifying their individual constitu‐ents.In this section,these quality-determining audio-visual prior materials are functionally re‐ferred to as intersemiotic translation models(or IST models).They are referred to as“models”be‐cause these starting texts offeraudio-visualpatterns thatare employable in an intersemiotic transla‐tion.

The term“model”is borrowed from Even-Zohar’s framework in his article“Factors and De‐pendencies in Culture:A Revised Outline for Polysystem Culture Research”(1997).Even-Zohar introduced“model”as“the combination of+the syntagmatic(‘temporal’)imposable on the product.”With these three basic conceptual elements,a model thus func‐tions within the producer’s repertoire to enable them to tackle a conceptual challenge.Even-Zohar emphasized that“a knowledge of order(sequence,or succession)is therefore an integral part of a model”to informthe text producerwhat to do.

Whatisto be perceived asthe primary eventofcross-culturaltranslation,and the key non-ver‐bal quality of film,is the visuality,which displays the culture through what Rey Chow terms as its“to-be-looked-at-ness.”The term“to-be-looked-at-ness”is taken from Laura Mulvey’s feminist arguments about“vision”and“looking”in her article“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”(1985).Mulvey’s feminist concern describes the gender inequality wherein women are more to be looked at by men than the other way around.Chow takes this term and applies it to the asymmetry of power between cultures,then moves further in arguing that“the state of being looked at not only is built into the way non-Western cultures are viewed by Western ones;but more significantly it is part of themanner in which such cultures represent—ethnographize themselves.”In this context,Chow defines“to-be-looked-at-ness”as“the visuality that once defined the‘object’status of the ethnographized culture and that now becomes a predominant aspect of that culture’s self-rep‐resentation.”Through films,the weaker cultures purposely expose themselves to the Western gaze and impose the way they are to be looked at or even“construct”themselves.Through these self-representations,film actively presents them as objects.Thus,“being-looked-at-ness,rather than the act of looking,constitutes the primary event in cross-cultural representation.”

To apply Chow’s theory to the present case,intersemiotic translation models(IST models)are themselves translations of cultures.They translate their embedded culture through transparent audio-visual constructions for their culture“to-be-looked-at”by members of different cultural groups.Audio-visual patterns are not merely the results of that culture’s cultivation,but are rather audio-visual constructions that are adopted by members of that cultural group to self-translate their own culture.Culture,in the multimedia age,is an audio-visual construct which spreads transpar‐ent images.In a sense,these audio-visual constructs could be referred to as“fables”or interpreta‐tions of the world.

At this point,it can be said that each ISTmodel is seen to be related to a culture and is signified both as a cultural lens of meaning-making and as a spectacle to represent the culture itself.What needs to be examined further is how to identify and categorize different groups of IST models.It is to this end that the following novel systemof ISTmodels is proposed.

The System of IST Models

Applying what Stuart Hall says about“systems of representation,”IST models are to be re‐garded as“systems”because they consist“not of individual concepts,but of different ways of orga‐nizing,clustering,arranging and classifying concepts,and of establishing complex relations be‐tweenthem.”

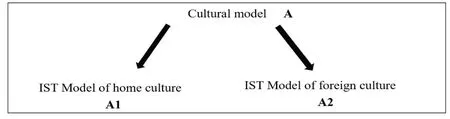

The system(see Figure 1)combines two hierarchized levels of the culturalmodel(A)and semioticmodel(B)with the channels of employment(C).This forms the basic methodology underpinningthe present study and the following section will introduce the key elementswithin this system.

Figure 1.Diagram of a System of IST Models

First Level:Cultural

The proposed system of IST models comprises two hierarchized levels.The first level of the system is the cultural model(see Figure 2).It is proposed as an arch-model that is subjected to thenationality or locale of the translator.

Figure 2.Cultural Model

The proposed term“culture model”is based on Even-Zohar’s conceptual scheme where the notion of model is affiliated to a cultural repertoire.“Cultural repertoire”is observed in the following way:“If we view culture as a framework,a sphere,which makes it possible to organize social life,then the repertoire in culture,orculture,is where the necessary items for that framework are stored.”

In this context,the culturalmodel in question is the culturalmodel for an intersemiotic transla‐tor who recognizes it as his/her model and who has been,supposedly,cultivated within a cultural community.Within the proposed system of IST models,cultural models also refer specifically to the artistic non-verbal starting texts which,according to Chow,represent or translate a culture through audio-visual“constructedness of the world.”This means the audio-visual constructions presented in these models are capable of translating the embedded culture“literally,depthlessly and naively.”Thus,these“transparent”cultural models are to be understood also as fables,the construction ofwhich represents interpretations of theworld.

According to Stuart Hall,culture can be defined as“the systems of shared meanings which people,who belong to the same community,group,or nation,use to help them interpret and make sense of the world.”Hall’s definition of culture may be useful in this context because it may be generally applied to three hierarchized levels of collectivity,which are allscales of human commu‐nities.“Nation,”in Hall’s observation,encompasses“group”and“community.”In the present study,Hall’s concept is chosen to frame the scale of culture,through groups of people,on the level of national locale.It is used here because the purpose of this paper is to discuss the role of mediation and communication between groups of people that are distinctly identified according to“a socia‐ble,populist and traditionary way of life,characterised by a quality that pervades everything and makes a person feel rooted or at home.”Culture is therefore considered,in this context,on a“nation-scale”which is themost collective level ofHall’s definition of culture.

The ISTmodels are dichotomized into the models ofculture(A1)and the models ofculture(A2).What is defined as“home”and“foreign”is identified according to the national origin of the translator.Accordingly,a translator’s home models refer to the models that originate from the translator’s national origin,while a translator’s foreign models refer to the models which belong to another culture that is different from the translator’s national culture.A clear example would be that inAng Lee’s case the compositional technique of a Chinese painting is a homemodel whereas the cameramovement technique of a French filmis a foreignmodel.Presumably,allmodels, like Iampolski’s intertexts,“bind a text to a culture,with culture functioning as an interpretive, explanatory,and logic-generating mechanism.”Examining the translator’s models,therefore,helps to reveal howthe translatormediates between cultures.

It should be stressed that rather than emphasizing how an IST model belongs to a specific cul‐ture,it is necessary to understand IST models as self-representations of their affiliated cultures.This applies to Chow’s theory of cultural translation in that“to-be-looked-at-ness”is the core con‐cern for cross-cultural translation.Elaborating on Chow’s theoretical context of the term,a culture can be translated with audio-visual patterns represented in IST models,because cultures,whether Eastern or Western,“third world”or“first world,”have become“infinitely visualizable surfaces”as words have been substituted by visuals.

Second Level:Semiotic

The lower level of the system is the semiotic model(B)(see Figure 3)which is differentiated by what Chow refers to as“modes of signification.”This sub-system is divided into the intersemi‐otic IST model(B1)and the intrasemiotic IST model(B2).The two models are dichotomized based on the semiotic system of the object of study.As the object of study in the present case is the film system,intrasemiotic IST models refer to the audio-visual patterns from within the filmic sys‐tem,whereas intersemiotic IST models refer to those outside the filmic system(such as painting,opera,and other non-verbal art forms).For instance,King Hu’s bamboo forest setting in the filmserves as an intrasemiotic model for Lee’s bamboo fighting sequence in,.To juxtapose,the light colour treatment style of Chinese ink-wash paintings serves as an intersemioticmodel forLee’s colour grading in,.

Figure 3.Semiotic Model

An IST model is thus always the result of a cross-level combination between the level of cultural models and the level of semiotic models.The cross-level combination categorizes an IST model by specifying both the hierarchy of its cultural locale and its semiotic nature.This cross-level connection results in the following four types of ISTmodels:

1.Home intersemioticmodels(A1B1):non-filmic audio-visual patterns which are realized within the translator’s home culture.

2.Home intrasemioticmodels(A1B2):filmic audio-visual patternswhich are realizedwithin the translator’s home culture.

3.Foreign intersemiotic models(A2B1):non-filmic audio-visual patterns which are real‐ized within a different culture.

4.Foreign intrasemiotic models(A2B2):comprise filmic audio-visual patterns which are realizedwithin a different culture.

Whilemediating specific effects on the parameters of filmlanguage on levelC(see Figure 1), these four identifiedmodel forms are the audio-visual patterns resulting from cross-semiotic combination in the system of IST models and may also themselves constitute rudimentary units for more complex forms of combination.There are caseswhere a translatormay use twomodels to support his translation of an ST segment.In this circumstance,the combinations can be intercultural, with both home and foreign elements in a constant dialogue and flowbetween them.

Intercultural Concatenation of IST Models

The translator’s intercultural combination of ISTmodels may be comprised of different units,where a unit refers to either a film sequence or a film scene.An intercultural combination of IST models may also be used to translate a single unit.In the case of film,intercultural models are not only a combination of models from different cultures,but also present an“exchange between cul‐tures.”

In Chow’s case,Chinese films,with their stories presented on screen,frequently comprise“an exchange between‘China’and theWest in which these stories seek their market.”She thus con‐cluded that“the production of images is the production not of things but of relations,not of one cul‐ture but of.”Chow’s argument concerning Chinese filmmakers may therefore be applied to ISTtranslators like Lee who,as a Chinese diasporic filmmaker,is constant‐ly confronted with the concept of China as his“home”in terms of his cultural roots,and the West as his“foreign”or adopted home,fromwhichChina can be looked-at froma distance.

If culture is regarded as a“system of shared meanings,”in which each IST model is influ‐enced by,and is a representation of,these shared meanings,through which a value is expressed,then it is by combining ISTmodels that an ISTtranslator creates a cross-cultural exchange.

As discussed above,each IST model is considered to amalgamate“rules,materials,and syn‐tagmatic relations”that are subject to a culture,and shared by the members of that culture.IST models,whether“home”or“foreign,”each represent an agreed cultural“lens”throughwhichmembers of that culture perceive their own culture and mores.These culture-specific lenses are therefore shared,and evolve,through the use of intercultural combinations of IST models.Through such a combination,an IST translator places segments of information,as well as their embedded cultural context,under a trans-cultural gaze.

Chow defines the concept of“gaze”as“to-be-looked-at-ness,”and as introduced earlier,this term describes the visual relationship between cultures where one culture is“looked at”by another culture through the medium of film.In Chow’s definition,this“looking”implies an ethnographic inequality,with“third world”cultures the passive“objects”under the visual scrutiny of the“first world.”However,she describes“to-be-looked-at-ness”as a mutually active engagement,where‐by the“to-be-looked-at”cultures self-represent,or even re-invent,themselves:“The visuality that once defined the‘object’status of the ethnographized culture now becomes that culture’s self-rep‐resentation.”

When applying Chow’s notion of“to-be-looked-at-ness”to the present case studies,what are“looked-at”are not only cultural objects,to be translated intersemiotically,but also the cultural lenses through which the IST models are viewed.In this case,the act of“looking”may be recipro‐cal.“Foreign”models may be looked at through a“home”lens,and vice versa.Each model may thus simultaneously be both the“viewed object”and the“viewing subject.”Hence intercultural combinations of ISTmodels are to be regarded as“interactive”in the sense that a“cross-cultural ex‐change”contributes to an enrichment of the audio-visual patterns of both the home and foreign cul‐tures,and this can be considered as a kind of intercultural“putting-together”through which a cul‐ture is brought to life by an ISTtranslator who translates each segment of information in the screenplay in terms of its complementary cultural interrelationships.

The Case of theVishnu Landscape

There are images of Vishnu figures in Lee’s translation of three of the scenes in the screenplay of,namely:“36 EXT.MUNNAR TEA FIELDS,1973-DAY”;“42.INT.PI’S BED‐ROOM,1973-DAY”;and“168 EXT.LIFEBOAT-NIGHT.”The Vishnu figure imagery was not,however,described in any of the three starting texts.The Vishnu images,in Lee’s translation of these scenes,are therefore to be understood as intersemiotic additions based on the context of the screenplay.This adaptation can be interpreted as a result of the translator’s personal creative choice.Through adding different images of the Vishnu figure as a visual motif,these scenes,which bear the same diegetic function,are intratextually connected:they suggest a divine eye watching over Pi as hemakes decisions thatwill change his life.

The imposition of the Vishnu images in Lee’s intersemiotic translation results from an inter‐cultural concatenation of two ISTmodels:the Mughal composite painting as a foreign intersemiot‐ic IST model,and the anthropomorphic landscape of Mount Guanyin as a home IST model.Lee’s combination of these two models contributes to the finalized intersemiotic translation of Vishnu landscapeimagery.

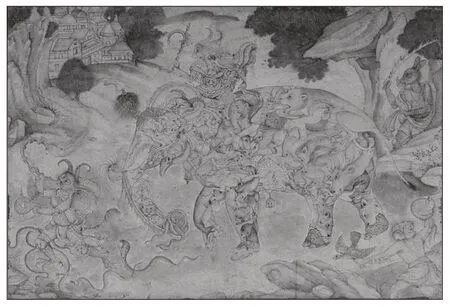

IST Model1:Mughal Composite Painting(A2B1)

Lee’s translation of the Vishnu figure landscapes firstly utilizes Mughal composite painting(see Figure 4)as a foreign intersemiotic IST model,setting up a relationship between the shell fig‐ure and its comprising visual components.Jean-Christophe Castelli,the co-producer of,commented on the pre-production fieldwork in India:“What Lee wanted at this early stage of the film’s development were background facts and ideas...The research forgrew out of the book and script...Indian local paintings,especially the composite paintings of elephants which are made up of other animals,contribute to the visual motif of the film.”The composite paintings of elephants hewas referring to belong to theMughal composite painting genre.

Figure 4.Composite Elephant,Mughal,Reign of Akbar,c.159034 Source:San Diego Museum ofArt,California.Cited in R.Del Bonta,“Reinventing Nature:Mughal Composite Animal Painting,”70.

Mughal composite painting first evolved in Northern India in the early Mughal period,hence their name.The Mughal composites are made up of disparate natural elements,most notably ani‐mal and human.This style of a painting often takes the form of an outline or shell figure which is composed of multiple disparate elements.For instance,in Figure 4,the elephant functions as the shell,inside of which the figures of humans and animals are artistically intertwined and combined in a creative mosaic.This style of painting indicates“the unity of nature which is intrinsic to Indian thought,and it often serves as a visual pun or metaphor indicating that things are not always what they appear to be but,instead,encompass layers of meaning.”It may reflect the Hindu religious belief in the unity of all beings and illustrate the doctrine of the transmigration of souls through suc‐cessive reincarnations.It may be inferred that this type of composite painting questions singulari‐ty,while producing a single immediate pictorial form that is simultaneously both connotative and denotative.

Mughal composite painting(Figure 4),as an Indian IST model,comprises a shell figure that is composed from various internal figures which hint at an interrelation between the dissected visu‐al elements,while also implying a unity between them.Its use contributes to the film’s visual motif as an exotic visual signification method.After establishing the motif as a visual model at the start of the film,Ang Lee then imported this stylistic feature into the translation model,as a shell+mosaic combination + composite visual element.Based on his appropriation of the Mughal composite painting,Lee then mediates an anthropomorphic landscape,and through the translation of Scene 42,Lee applies the above-mentioned composite model to his translation of landscapes by having the geographical elements representVishnu as the shell figure,to be filled by various internal com‐ponents of visual elements to translate Scene 36 and Scene 168.Here the composite visual motif comes from Mughal composite painting,a foreign intersemiotic IST model,whereas the imagery of the anthropomorphic landscape comes from the actual landscape of Mount Guanyin in Taipei City.This landscape is to be regarded asLee’s home intersemiotic ISTmodel.

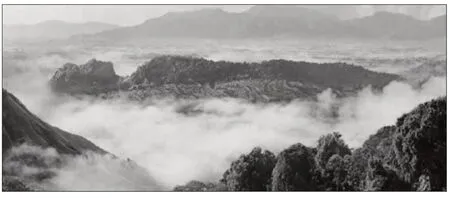

IST Model2:The Anthropomorphic Mount Guanyin(A1B1)

Mount Guanyin is an inactive volcano in New Taipei City in Taiwan(see Figure 6.3.2),named after the Guanyin Pusa(Chinese translation ofAvalokiteśvara,also translated as Kuan-Shi-Yin by Kumārajīva),as the landscape shares a visual resonance with the form of the goddess(see Figure 7).According to《重修凤山县志》(Rewritten Gazetter of the Fengshan County),“The landscape of Mount Guanyin is undulating and sinuous.Acliff stands out in the middle,like a seated Bodhisattva.”This interpretation of the landscape can be found in《台湾地名辞典》(Gazetteer of Taiwan Place Names),indicating that Mount Guanyin is named after Guanyin Pusa because the shape of the landscape resembles the contours of herface.

According to Branigan,“anthropomorphism assigns human or personal attributes to an ob‐ject that is not human.”In the present case,the concept of anthropomorphism is employed to de‐scribe the landscape of Mount Guanyin using the attributes of a human(or divine)figure.Figure 5 illustrates visually Mount Guanyinas the shape of Guanyin’ssolemn face facingup(Figure6).

Figure 5.Mount Guanyin in New Taipei City39 Source:picture retrieved from:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Guanyin_(New_Taipei),[April 23,2021].

Figure 6.Visual Illustration of the Landscape-Face Relationship41 Source:picture retrieved from:https://tamsuitour.pixnet.net/blog/post/149178696,[April 23,2021].

It is highly likely that Lee has adopted the second version(see Figure 7),as he commented on this point“I built the island according to my memory.In my design,the body parts above the neck take on a resonance with Mount Guanyin.”

Figure 7.Resonance between the Landscape of Mount Guanyin and the Face of Kuan-Shi-Yin Pusa

Figure 8.Establishing Shot of the Vishnu Image56 Source of film still:Life of Pi,directed byAng Lee(Time:00.17.47-00.18.12).

The mountain tends to be imagined by people as an embodiment of spirit and is thus perceived as an object of worship,although the mountain itself has no spirit.It should be emphasized that the landscape does not function as a text per se and it is only text because it is perceived by humans as text.The textuality lies not in the landscape itself,but in the way the landscape is read by its cultur‐alized and socialized viewers.The way of reading a landscape makes the landscape into a sign,so that in the Barthesian sense it“says something but refers to something else.”How one perceives a landscape is thus how one establishes a signifying practice.The text,as a signifying practice,is it‐selfatranslation:a meaningless landscape is thus translated through its interpreta ntintoameaningmaking device and the established relationship between the sign and the object is to be regarded as a translation.In this way,Mount Guanyin matches the criteria of being a text:it is a combination of sensory signs carrying communicative intention.If it is continually serving as a normative meth‐od of reading the landscape,then the anthropomorphic landscape itselfbecome a translation model for the future appreciation of that very landscape.

That Mount Guanyin serves as Lee’s IST model is evidenced in his comment:“It is true I hide Mount Guanyin in the imagery in the floating carnivorous island...I hid three imageries of Mount Guanyin.”Lee also remarks that Mount Guanyin is a sign he is familiar with:“When I was in high school,I would walk pass Nanxing Bridge.I would just stand there and gaze at Mount Guanyin in a daze.I have made videos and written articles on this mountain.”As a home intersemiotic ISTmod‐el,the anthropomorphic Mount Guanyin presents a text as it embodies Lee’s imagination of a su‐pernatural god that transcends him and is watching over him as well as therest of the world.

Mount Guanyin,as a cultural text,is itself correlated with a logic-generating system.Firstly,it coincides with a supernatural anthropomorphic perception of a landscape.This landscape-read‐ing perspective must be correlated with Ang Lee’s home cultural poetics.This connects to the es‐sence of Stuart Hall’s definition of culture,i.e.,a system of shared values with which the cultural members make sense of the world.Amountainous landscape stimulates a mystification of nature,which is closely related to mythologies shared by cultural communities.Such a mythological readingof nature is perhaps best illustrated by Lu Xun 鲁迅(1881-1936):

When primitive men observed natural phenomena and changes which could not be ac‐complished by any human power,they made up stories to explain them,and these explana‐tions became myths.Myths usually centered round a group of gods:men described these gods and their feats and came to worship them,singing hymns in praise of their divine pow‐er and making offerings in their shrines.And so,as time went by,culture developed.For myths were not only the beginning of religion and art but the fountain-head of literature.

Secondly,it correlates to the culture of Chinese Mahayana Buddhism.According to the Buddhist Lotus Sutra,Guanyin appears in the human world in various forms or images to enlighten mun‐dane lives.These forms may reappear visibly as Guanyin’s face,which is known as法相(a term for“phenomena”translated as“Dharma”by Venerable Cheng Kuan 2014).This is de‐scribedindetailinthe:

Virtuous Man,in a certain Buddhaic Universe,if there be some Multibeings who are meant to be delivered by one in the Buddhaic form,Kuan-Shi-Yin Pusa would manifest a Buddhaic form to divulge the Dharma for them;if they are meant to be delivered by one in theform,he would manifest theto divulge the Dharma for them...

Thegoes on to describe thirty-two forms in which Kuan-Shi-Yin Pusa may manifest,namely,“Buddha,”“Pratyeka-buddha,”“Auricular,”“Celestial Brah‐man-King,”“Shakya-Devanam,”“Masterful Celestial,”“Great-Masterful Celestial,”“Vaisrava‐na Celestial,”“lesser Potentate,”“Patrician,”“lay practitioner,”“Perfect,”“Brahmin,”“Bhikusu or Bhiksuni,”“upasaka or upasika,”“womenfolk,”“lad or lass,”“Deva,”“Dragon,”“Yaksa,”“Gandhabha,”“Asura,”“Garuda,”“Kinnara,”“Mahoraga,”“human,”“quasi-anthropoid,”and“Vajra-bearer Deity.”Accordingly,the many avatars of Kuan-Shi-Yin Pusa influenced the way in whichnatural landscapesare“looked-at”and perceived as an embodiment of Pusa’sDharma.

In Lee’s context,these two poetics behind Mount Guanyin,as a model to represent Vishnu,come from the fact that the legends of Vishnu and Guanyin resonate with each other in the way the two deities reveal themselves in different incarnations(or Dharma),to enlighten their believers at the times when they are most needed.In Hindu mythology,Vishnu,as the major Hindu deity,has innumerable incarnations.According to the Hindu purana:“O brāhmanas,the incarnations of the Lord are innumerable,like rivulets flowing from inexhaustible sources of water”(1.3.26).Among these avatars of Vishnu are ten which are celebrated as his major appearances.These are“Matsya”(the fish),“Kurma”(the tortoise),“Varaha”(the boar),“Narasimha”(the lion man),“Vamana”(the dwarf),“Parashurama”(the sage with an axe),“Ra‐ma”(Hindu deity),“Krishna”(Hindu deity),“Buddha,”and“Kalki”(the man with a white horse).This resonates with the legends of Guanyin’s revelation through a transcendent form.In this case,Guanyin andVishnu may be interrelated,with Guanyin being the interpretant to translate Vishnu,not only because both are culturalized religious heroes,but also because of the similarity in theway they unfold their heroic powers,i.e.,by incarnating their divine selves in various forms.

In this case,the combination of two figures is to be understood as an employment of ISTmod‐els to make up for each one’s deficient semantic capability.That Lee combines two signs from two different religious cultures has to be understood as employing an interpretant within the framework of semiotics.According to Iampolski,an interpretant refers to how one makes sense of a sign.In Lee’s case,Mount Guanyin is employed not only as an IST model,but as Lee’s interpretant for the foreign mythological context.In this case,Guanyin is the sign that Lee is familiar with,whereas Vishnu is an alienated sign which Lee must make sense of.Mount Guanyin,through correlating to the interconnection between a natural deity and Buddhist teaching,serves as the interpretant for Lee to make sense of signs from the Indian mythological universe.

Thus,the combination of the foreign intersemiotic IST model and the home intersemiotic IST model achieves the following semantic result:the home intersemiotic ISTmodel leads to the estab‐lishment of the anthropomorphic landscape,while the foreign intersemiotic IST model leads to the meta-textual design of a composite figure.The shell figure takes on the formof theHindu God Vishnu as the Indian culture’s visual symbol.

Concatenation of the Two IST Models in Action

The design of a Vishnu landscape also follows this translation model.Lee’s employed shell figure does not dissect immediately to show the stylistic mosaic composition.Instead,this visual motif is translated through a loose and hidden intratextual connection,by interrelating the translationof the three separate sequencesmentioned above.

Example 1.Establishing the shell figure.

:

42.INT.PI’SBEDROOM,1973-DAY

PI:Thank you,Vishnu,for introducingme to Christ.

ADULT PI(V.O.):I came to faith through Hinduism and I found God’s love through Christ,butGodwasn’t finished with me yet.

Vishnu,as a shell figure,is introduced through the translation of Scene 42(see Figure 8).The screenplay describes an interior sequence of young Pi praying to the idol of Vishnu in his bedroom.The screenplay gives no further description of the interior environment or further details of Pi’s bedroom,and invites the director’s creativity to fillin these blanks.The close-up ofthe idolof Vishnuis themost significant adaptation.

The time is set in the evening,shortly before Pi goes to sleep.Pi places his right hand piously on the idol.The shot is an extreme close-up shot of Pi’s upper body facing left,which only involves Pi and the idol of Vishnu in the frame,thus emphasizing the interaction between the two.The cam‐era pans slowly from left to right,from the idol of Vishnu,neatly placed on Pi’s bedside table,to the worshipping Pi.The camera focus switches from the idol to Pi as it pans.After Pi gives thanks,heprayswithanIndiangesture:handspressedtogether,palmstouchingandfingerspoint‐ing upwards with thumbs close to the chest.He then turns off the light and lies down to sleep.The camera then pans slowly fromright to left,back to the idol ofVishnu.

With the lamp now turned off,a low-key lighting effect which simulates moonlight casts a contour light onto the figure of the idol from directly above.Since it is now at the centre of the frame,and a close-up,the viewer is able to register clearly that Vishnu is lying down and sleeping on top of the serpents which protect him.The camera stays static for four seconds on the idol,with the adult Pi’s voiceover on the soundtrack.The function of static shots and the contour lighting is to emphasize the significance of the character and figure of the idol.The background voiceover men‐tions God in order to connect the divine observance within Pi’s mind with the Hindu god Vishnu’s recumbent image.This is the first time the recumbent figure of Vishnu is pictorially and concretely depicted in the form of the Hindu god.It also symbolizes the concept of God which Pi constantly re‐fers to throughout the film.The Vishnu figure therefore functions as an indication of the broader sense of a divine power beyond a narrowly defined concreteHindu character.

Example 2.Hidden design-Vishnu-likemountain tops.

:

36EXT.MUNNARTEAFIELDS,1973-DAY

.

Earlier in the film,before the Vishnu figure is introduced in its corporeality,it appears as a hidden background design,as a translation of Scene 36 through the concatenation of the model of MountGuanyin(A1B1)andMughal composite painting(A2B1)

The shot is amasterwide-angle shot of the farmlands in themountains(see Figure 9).The foreground is a peaceful Indian countryside setting with tea fields,farmers working,and winding mountain roads.The background design presents a grand theme of nature,with clouds and mists surrounding the greenmountains.Itwould seemlike an image-to-image translation,apart fromthe detailed components of farmers andwinding roads,but a closer examination of themistymountain in the background(see Figure 10),reveals an anthropomorphic landscape in the shape of a recumbentVishnu that is explicated later in the film.

Figure 9.Landscape Shot of Munnar Tea Fields58 Source of film still:Life of Pi,directed byAng Lee(Time:00.15.25-00.15.33).

Figure 10.Detail of Vishnu Landscape in the Background59 Ibid.

It should also be mentioned that this master shot was edited with the camera tilting vertically fromthe sky to themountains to alignwith the theme of divine instruction.This movementmanipulates the landscape design to imply thatPi’s adventure is instructed byGod,and that it isGod that introduces Pi to Christ.This directorial addition of a hidden design serves as an indicator of“God’s instruction,”and may be unnoticed by many viewers as one of the several concretizations for the grand landscape background.Lee’s addition of face-like landscapes correlateswith the abstract notion of“God”that Pi repeatedly emphasizes.Lee’s use of landscape as the meaning-making machine can also be considered as a tribute to the function of film art as an art of index,but Lee does notmake the indices as concrete and clear as he does in Figure 8.There is no arbitrary statement given by the director that the mountain is a projection of Vishnu and not just a simple set of remote mountaintops cloakedwith green trees.The duality of this design is that it tries tomake an implicationwhile notmaking itself obviously visible.TheVishnu-likemountain figure is positioned in the background of the frame,and the brevity of the sequence is aimed at distracting the audience’s attention away from it.The unexplained loose face-landscape connection is,however,emphasized in the next example,where it appears on screen for the last time.

Example 3.Vishnu-like carnivorous island.

:

168EXT.LIFEBOAT-NIGHT

-’,,--.

The master shot sequence of the Vishnu landscape is perhaps the most thrilling sequence in the entire film.Like the previous examples,this sequence is a directorial addition to the setting of the ST.The ST,as indicated above,demands an over the shoulderwide-angle shot frombehind the tiger(see Figure 11)which shows the bioluminescent island contracting and expanding with waves lapping on its shore as if itwere breathing,and sporadic background pianomusic to strengthen the atmosphere.

By splitting a single shot into two separate shots,Lee dramatically prepares the revelation of the landscape with the whole island—a recumbent luminous anthropomorphic figure(see Figure 12).The landscape slowly zooms out with the sporadic lights expanding and flowing through the whole island like blood through veins.The greenish colour is surrounded by the darkness of the vastsea,which casts a bright contour light on the island’s shore.The lighting contraction forces the au‐dience to concentrate on the appearance of the island.The greenish light contrasts with the dark‐ness and establishes a haunted,luminous effect.The background music accompanying the shotstarts with the low-pitched chorus and the base soundtrack creates a ghostly and suspicious atmosphere.Thewoodwind further emphasizes the sense of horror andmystery.

Figure 11.Medium Shot of Richard Parker Looking at the Island62 Source of film still:Life of Pi,directed byAng Lee(Time:01.40.16-01.40.21).

Figure 12.Landscape Shot of the Island63 Ibid.(Time:01.40.21-01.40.29).

Unlike Examples 1 and 2,this sequence emphasizes the complete horizontal viewof the landscape, with the music in the previous shot preparing the audience to expect and concentrate on the filmic revelation landscape.This is the third time that the recumbent man-like figure appears on screen.This time Lee does not try to hide the portrait as an implication,but rather uses deliberate emphasis.It must be stressed that all three cases intra-textually relate to each other due to visual similarity.Based on the concrete presentation of Lord Vishnu’s statue in the first example(Figure 8),it can be seen thatLee builds a face-landscape connectionwith the face/appearance ofVishnu in both themountain figure and the island figure.

Deleuze and Guattari suggest that“the face is what gives the signifier substance:it is what fu‐els interpretation,and it is what changes,changes traits,when interpretation reimports signifier to its substance...the signifier is always facialized.”According to Deleuze and Guattari,“all faces envelop an unknown,unexplored landscape;all landscapes are populated by a loved or dreamedof face,develop a face to come or already past.”In Lee’s case,the landscape-face connection is manifested in a combined representation of a face/statue landscape.The viewers observe the idol and the island at the same time.This establishes a“white wall/black hole system.”According to De‐leuze and Guattari,“[s]ignification is never without a white wall upon which it inscribes its signs.Subjectification is never without a black hole in which it lodges its consciousness,passion,and re‐dundancies”.It is this system that constitutes all semiotics.In the present case,the island presents a white wall of signifier and the idol shape of the island manifests the black hole cut into the“white wall”of the island figure for Lee’s intended signification,making theVishnu island resemble a De‐leuzian“face”in this regard.In doing so,Lee makes this interconnected idol/landscape representationan efficientmeaning-making device.

TheVishnu figure landscape corresponds to Pi’s first account of his divinely-ordained adventure:“EvenwhenGod seemed to have abandonedme,hewaswatching.”This interconnection betweenGodand Pi’s adventure is repeatedly emphasized and comes back onto the screen twice.The implementation of an idol-landscape connection on the floating island also introduces a sensational surreal experience and,along with the night-time setting and the backgroundmusic,establishes an unknown andmysterious theme.Themystifying atmosphere foreshadows Pi’s horror at discovering the truth that thewhole island is in fact carnivorous.Lee’s adaptationmay also strengthen theimplication that it is the surreal power of God that alerts Pi to the danger and urges him to leave the island,for as Pi recalls,“he gaveme a sign to continuemy journey.”

Beside the embodiment of the deity in the landscape,and the omnipresent interconnections and incarnations of souls that are communicated through the many signifying practices,e.g., MountGuanyin andMughal composite painting introduced byLee as his ISTmodels,such a“reading” of Lee’s imagery also needs to be correlated with the foreign cultural context behind Vishnu, the sign forwhich Lee’s representation serves as an interpretant.InHindumythology,Vishnu avatars appearwhenever the cosmos is in crisis.This is described in the:

Whenever and wherever there is a decline in religious practice,O descendant of Bhara‐ta,and a predominant rise of irreligion—at that time I descend myself.In order to deliver the pious and to annihilate the miscreants,as well as to re-establish the principles of religion,I advent myself millennium after millennium(4.7-8)

Accordingly,in Lee’s translation of Scenes 36,42,and 168,the Vishnu landscape imagery is in‐voked as a culturally concretized semiotic to reveal the horrible truth about the carnivorous island.The Deleuzian face-landscape relationship is thus visualized through the“firstness”of the Vishnu figure,packaged under an intercultural mediation of Mount Guanyin and composite visual code.That Lee’s established face-landscape relationship may also be correlated with what Iampolski de‐scribes as“hieroglyphs of intertextuality”results in a textual anomaly that the audience has to make sense of by seeking its roots outside the film text.This then firmly connects the textuality of Lee’s translation as an intertext that connects itself to a logic-generating system behind the two ap‐propriated models.In other words,Vishnu and Guanyin,as cultural semiotics of gods,relate to Lee’s inserted intertext,which contextualizes Lee’s Vishnu landscape,both within and without Lee’s foreign culture,by constructing God through a combination of Hindu and Buddhist deities.To this end,theVishnu landscape is enabled to be understood via an in-depth“reading”and can be interpreted as a meaning-making device of which the“actualization”is offered through establish‐ing an interconnection behind the cultural information that the models represent.In this sense,meaning is communicated by linking the Vishnu landscape to a sign of“thirdness”by making the Vishnu figure related to the cultural script of Hinduismand Buddhism.

If,however,the focus is not on“reading”but on“transaction,”and visuality is to be“without depth,”then the Vishnu landscape can be analysed solely for the quality of its“to-be-looked-atness,”resulting from the two perspectives provided by Lee’s appropriated visual patterns that are represented in the two IST models.This“to-be-looked-at-ness”emphasizes the visual“expres‐sion”of the Vishnu landscape.In this sense,what is emphasized is the“firstness”of the putting to‐gether of two distinct visual traits that is totally free from any concretized connections to any“ob‐jects.”

For Deleuze,“firstness”refers to“the qualities or powers considered for themselves,without reference to anything else,independently of any question of their actualisation.It is that which is as it is for itself and in itself.”This firstness can also be interpreted as a sign of mystery when no ex‐planation of the background is given by the intersemiotic translator and the spectator perceives nothing concrete other than the visuality of the figure themselves.This may be applied to the pres‐ent cases,since the first two appearances of the Vishnu landscape are hidden designs that the spec‐tators might not even notice.The three inserted imageries are intratextually so loosely interrelated to the extent that their spectators may not establish a connection with the established concretized shell figure in Example 1 and the hidden design in Example 2 and move on without a second look.Presumably,the anthropomorphic landscape which results from Lee’s appropriation of home and foreign IST models is represented as an experience of firstness for its sheer visuality,i.e.,“[it]expressesthe possiblewithout actualising it.”

It is worth noticing that Lee does not seek to make an explicit link between the figure of Lord Vishnu and the figures that Pi confronts in his adventure by making this connection concrete.It per‐mits the viewer to constantly contemplate on the meaning behind an idol-like landscape through which they themselves select their interpretants.It also stimulates the viewer to identify the idol through a constant imagination of the potential correlation between the figure and the elements,or characters,ofthefilm.

By comparing the second narrative of Pi’s adventure,a popular explanation is that the carniv‐orous island symbolizes the corpse of Pi’s mother which Pi feeds on when he’s dying,since the fig‐ure resembles a recumbent female(see Thorn 2015 for an example).Interconnected with the vision of Vishnu,the Vishnu-like island figure may be interpreted as standing for the consolation that Pi seeks from religion while eating his mother’s corpse,just as he seeks consolation after he kills a do‐rado fish in the earlier sequence by praying“thank you Lord Vishnu...for coming in the form of a fish and saving our lives.”

The face-landscape connection may imply the answer that is needed when facing profound questions or a dilemma which Pi cannot explain,such as the question How does one finds reli‐gion?”None of these interpretations are justified by Lee and yet these interpretations are nonethe‐less permitted by his adaptations as they highlight,to a visible degree,the surreal divine religious interconnection behind Pi’s adventure which Lee intends to discuss.Not establishing a solid semioticconnection,Lee’s imposed landscapes become signs of mystery which only stimulate the spectator’s curiosity.These Vishnu landscapes,therefore,create a meaning-making device which ismystified by the absence of an explanation fromLee.

Roland Barthes writes that“myth is not defined by the object of its message but by the way in which it utters this message.”Accordingly,mystery is translated by not going beyond the“first‐ness”of the sign,even though knowing that the sign itself is clearly related to something.In this way,the loose connection made with“Vishnu-island”is to be understood as a sign of firstness,i.e.,it is“as it is for itself and in itself”and is independently of any questions of its actualization.The referencing is absent not because it does not exist,but because its connotations are purposefully withheld by the translators to make this sign of the firstness mystical.As Ludwig Wittgenstein ob‐served,“It is notthings are in the world that is mystical,butit exists.”In Lee’s case,it is not what the shapes mean or what idol they refer to,but the fact that they are portrayed in the like‐ness of a meaningful idol-like figure with no explanation that haunts the spectators as mysterious icons to invite their interpretations onLee’s deepermeaning behind it.

Regarding the intention of directorial adaptations,Lee’s personal response provides a useful insight:

I am not very clear about what I did throughout the film;it is difficult for me to utter in a rational way what is irrational in my creation.Nevertheless,it would destroy the mysteri‐ousness of my film if I were to explain what I had intended to do.

Lee’s comment,which is not very different from what many directors might say when confronted with the question“What do youmean?”may be interpreted in twoways:

Firstly,Lee claims that he cannot explain the meaning behind his icon and so he cannot give a concrete explanation for his creation.Rey Chow remarks that similar excuses make the director a seducer who does not consciously know that he is seducing even though he is fully engaged in the game of seduction.Chow observes that such seduction follows the enigmatic traps a director sets“in order to engage his or her viewers in an infinite play and displacement of meanings and surfac‐es,to catch these viewers in their longings and desires,making them reveal passions they nonethe‐lessdo notfully understand.”Itstimulatesthe textreceivers’curiosity asthe represented exotic elementstranslate mysteriousness concerning“that it exists”rather than“howthings are.”

Secondly,Lee’s comment may be understood as his refusal to offer clear meanings.Lee says“I would like to represent the growing up process of us humans in which things we’ve encountered,be that God or the entire life,are actually absurd with no meaning.”Lee’s remark coincides with the adult Pi’s line in the film:“If it happens,it happens,why should it have to mean anything?”Such an explanation,however,is clearly unconvincing,since it contradicts Lee’s earlier remark that the purpose of story-telling is the communication of meaning.Why seduce the spectators with clearly connotative signs and connect them intertextually if it does not have to mean anything?This refusal may only be explained by Lee himself as an intention to retain a“mystery of cre‐ation.”It may also be contemplated as Lee’s anticipation of an upcoming endless interpretation process triggered by his translation.Lee remarks that“meanings are manmade to make sense out of these random absurdities by telling stories.”Intentionally forsaking his opportunity to give an of‐ficial explanation,Lee lures the spectators into initiating a meaning-making process between Lee’s onscreen reality and other possible realities which may lead to an infinite interpretation which they themselves do not fully understand.The result of such meaning-making processes varies from individual to individual as,according to Wittgenstein,one reaches a final interpretation only at“a psychological rather than a logical terminus”.

Consequently,through Lee’s Vishnu landscapes,a theist may see the power of religion,an atheist may see the denial of religion,and a pessimist may see the possible truth.Anew viewer will always be able to start the interpreting process afresh.One could say that by leaving the imposed meaningful visual components unexplained,a director makes his or her intersemiotic translation alive yet deeply enigmatic.

Conclusion

Intersemiotic translators are not only translators of a specific culture,but also initiate ex‐changes between cultures.A further intention of this cultural exchange is to appeal to a target cul‐ture.Each IST model belongs to a cultural repertoire.These IST models may therefore be consid‐ered as being subject to different cultural poetics,so an IST model can be chosen to appeal to a tar‐get culture whose members are already familiarized with the audio-visual patterns specific to that culture.

If,however,an IST model is to be enabled from beyond the consumption-oriented frame‐works,and each model is considered to be a lens through which a culture is perceived,this repre‐sents a translation of these culturally specific visual spectacles,and therefore invites a transnation‐al gaze.This transnational gaze applies to the case ofVishnu landscape which have been discussed,where Ang Lee employs and combines multiple IST models,or audio-visual patterns,in order to communicatehis“intention.”

Lee’s remark in an interview about his film,epitomizes why an ISTtranslator needs to employ IS Tmodels inter-culturally:

With“Crouching Tiger,”for example,the subtext is very purely Chinese.But you have to use Freudian orWestern techniques to dissect what I think is hidden in a repressed so‐ciety—the sexual tension,the prohibited feelings.Otherwise you don’t get that deep...To be more Chinese you have to be Westernized,in a sense.You have to use that tool to dig in there and get at it.

So how does an ISTtranslator“get deeper”by putting his/her“home”culture under a“foreign”gaze or vice versa,and how,through an inter-cultural combination of models(described by Lee as“techniques”),may atranslator“dig in thereand getatit”?To answerthesequestions,onehasto re‐turn to the creative process of“putting together”as suggested by Walter Benjamin’s framework in his essay“The Task of the Translator.”Chow suggests the process of“putting together”is appropri‐atedfromBenjamin’s“gluing together”which he describes as follows:

Fragments of a vessel which are to be glued together must match one another in the smallest details,although they need not be like one another.In the same way a translation,instead of resembling the meaning of the original,must lovingly,and in detail,incorporate the original’s mode of signification,thus making both the original and translation recogniz‐able as fragments of a greater language,just as fragments are part of a vessel.

Chow interprets Benjamin as proposing a“liberation,”in the sense that“both‘original’and‘trans‐lation,’as languages rendering each other,share the‘longing for linguistic complementarity’and gesture together toward something larger.”Chow elaborates Benjamin’s notion of“origin”and “translation,”suggesting that“original”may refer not only to somethingwritten in the“original language,”but also the“native/original language of the native speaker/translator.”Similarly,“trans‐lation”may refer to“not only the language into which something is translated but also a language foreign to the translator’smother tongue.”

Chow’s interpretation may be applied to the present dichotomy of“home”and“foreign”cul‐tural IST models,where“original”refers to the“home”IST models which are in the translator’s mother tongue.In the same way,“translation”may refer to the translator’s“foreign”cultural mod‐els which manifest as different audio-visual patterns.Thus,the inter-cultural combination of IST models corresponds to the underlying principles of Benjamin’s argument:“home”should let the“foreign”“affect,or infect,and vice versa.”Mastering such a combination is what Benjamin refers to as“the task of the translator”:

It is the task of the translator to release in his own language that pure language which is under the spell of another,to liberate the language imprisoned in a work in his re-creation of that work.

Accordingly,what Lee refers to as“hidden”is what Benjamin refers to as an“imprisonment.”This describes the under-translated and neglected information in that culture.This information is undertranslated in that it is not referred to or visually represented,and is therefore“imprisoned.”These hidden messages may only be liberated by means of a supplemental model from a culture and lan‐guage that is different from their own.In this way,therefore,“imprisoned”cultural information is supplementedby“foreign”ISTmodels.

For instance,the anthropomorphic landscape of Chinese IST models functions as a liberation for“imprisoned”Indian IST models and vice versa.Together,each employed model translates the hidden information within the representational deficiency of each other.In this case,it is Lee’s in‐ter-cultural combinations of ISTmodels that translate and visually create the hidden cultural mean‐ing in the screenplay.It is through this“putting together”that Lee’s translation contributes to a cinematicpresentation of the hidden or imprisoned elements.

This combination may be explored through the concept of“pure language,”which Benjamin explains thus:“All supra-historical kinship between languages consists in this:in every one of them as a whole,one and the same thing is meant.Yet this one thing is achievable not by any single language but only by the totality of their intentions supplementing one another:the pure lan‐guage.”

In the present case,IST cultural models are each considered as fragments of that“pure lan‐guage.”In turn,thepurelanguageisconsidered asacompleteoruniversallanguagewhich commu‐nicates beyond cultural or national boundaries.If the system of ISTmodels presents a dichotomy of“home culture”and“foreign culture”sources,this inter-cultural combination of IST models,with each model dependent on the clear conceptual boundary between“home”and“foreign,”violates that boundary.The IST translator can therefore be seen to enable audio-visual patterns comprised of different cultures that are constantly in dialoguewith each other.

If an intercultural combination of IST models is considered as a“putting together”of“frag‐ments,”then it is by the“putting together”of these IST models that the IST translator accomplishes a re-construction of the“greater language”:a language that is efficient in translating the segments of messages and their cultural context through audio-visual images.In the case studies discussed here,it is through this“putting together”that Lee communicates his creative intention beyond cultures,and yet taps into universal ideas that are common between cultures.

Barthes,R..Translated byA.Lavers.London:Vintage,2000.

Benjamin,W.“The Task of the Translator.”In.Edited by H.Arendt.Translated by H.Zohn.New York:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,1968/1923,69-82.

Bennett,K.“Star-Cross’d Lovers in theAge ofAIDS:Rudolf Nureyev’s Romeo and Juliet as Intersemiotic Translation.”In:.Edited by M.P.Punzi.NewYork:Peter Lang,2007,127-44.

Branigan,E.:NewYork and London:Routledge,2006.

Bryant,E.:NewYork:Oxford University Press,2007.

Castelli,J.C.:NewYork:Harper Collins Publishers,2012.

Chan,K..Hong Kong:Hong Kong University Press,2009.

Chow,R.:,,,.New York:Columbia University Press,1995.

Del Bonta,R.“Reinventing Nature:Mughal CompositeAnimal Painting.”InEdited by S.P.Verma.Mumbai:Marg Publications,1999,69-82.

Deleuze,G.,and F.Guattari.:.Translated by B.Massumi.Minneapolis:University of Minnesota Press,1987.

Deleuze,G.:.Translated by H.Tomlinson&B.Habberjam.London:Continuum,2005.

Dusi,N.“Intersemiotic Translation:Theories,Problems,Analysis.”206(2015):181-205.

Even-Zohar,I.“Factors and Dependencies in Culture:ARevised Outline for Polysystem Culture Research.”XXIV,no.1(1997):15-34.

——.“The Position of Translated Literature within the Literary Polysystem.”11,no.1(1978):45-51.

Gorlée,D.L.:.Tartu:Tartu University Press,2015.

——.“Meaningful Mouthfuls in Semiotranslation.”In,.Edited by S.Petrilli.Amster dam:Rodopi,2003,235-52.

Hall,S.“New Cultures for Old.”In?,.Edited by D.Massey and P.Jess.Oxford:Oxford University Press,1995,175-213.

Hartman,G.NewYork:Columbia University Press,1997.

Iampolski,M.:.Berkeley,California:University of California Press,1998.

Jakobson,R.“On LinguisticAspect of Translation.”In.2nd ed.Edited by L.Venuti.NewYork and London:Routledge,2004/1959,138-43.

Kress,G..London and NewYork:Routledge,2003.

Lee,Ang,dir..2012;LosAngeles,CA:Fox 2000 Pictures,Dune Entertainment,Ingenious Media,Haishang Films,Big Screen Productions,Ingenious Film Partners,Netter Productions.Blu-ray Disc,1080p HD.

Lochtefeld,J.Vols.1&2.NewYork:Rosen Publishing,2002.

Lu Xun..Translated byYANG Xianyi and GladysYang.Beijing:Foreign Languages Press,1976.

Magee,D.LosAngeles:Fox 2000 Pictures,2010.

Mulvey,L.“Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.”In:.Edited by B.Nichols.Berkeley and LosAngles:University of California Press,1985,303-15.

Perdikaki,K.“FilmAdaptation asAnAct of Communication:Adopting a Translation-orientedApproach to the Analysis ofAdaptation Shifts.”62,no.1(2017):3-18.

,(1972).Translated byA.C.Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupāda.Los Angeles,California:Bhaktivedanta Book Trust.Available online at:https://vedabase.io/en/library/sb/1/,[April 23,2021].

.Translated by K.Cheng.English Edition.Taipei:Neo-carefree Garden Buddhist Canon Translation Institute,2014.

Thorn,M.“Cannibalism,Communion,and Multifaith Sacrifice in the Novel and Film.”27,no.1(2015):1-15.

Torop,P.“The IdeologicalAspect of Intersemiotic Translation and Montage.”41,no.2/3(2013):241-65.

Wittgenstein,L..Edited by G.E.M.Anscombe and G.H.von Wright.Translated by G.E.M.Anscombe.Oxford:Basil Blackwell,1967.

——.Translated by D.F.Pears and B.F.McGuinness.London:Routledge&Kegan Paul,1961.

Yau,W.“Revisiting the SystematicApproach to the Study of FilmAdaptation as Intersemotic Translation.”9,no.3(2016):256-67.

(清)王瑛曾总纂:《重修凤山县志》,台北:(中国)台湾银行经济研究室,1962[1764]年。

[WANGYingzeng,ed.(Rewritten Gazetter of the Fengshan County).Taipei:Taiwan Institute of Economy Research,1962(1764).]Retrieved online from:https://ctext.org/wiki.pl?if=gb&chapter=532388,[April 23,2021].