Man vs. Wild

2022-05-30NingyiXi

Ningyi Xi (席宁忆)

Urbanization, habitat loss, and even successful conservation are leading to increased human-wildlife conflict

人獸冲突加剧,生物多样性与人民生命财产安全如何兼顾?

Illustration by Xi Dahe

Photographs from vcg

On the morning of May 8, 2022, six young and two adult wild boars were spotted in a residential complex in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, some of them feasting on plants in the yards behind ground-floor apartments. It ultimately took a joint effort from the complexs security guards, local firefighters, and the police to evacuate the boars into the woods nearby.

Hangzhou, a city of more than 10 million residents, has reported multiple wild boar sightings in populated areas in recent years, with one boar even entering a shopping mall in broad daylight. Although local media tend to portray these incidents as thrilling episodes in urban dwellers lives, such encounters in rural areas can have far more severe consequences. News portal Zhejiang Online reported that, in June 2019, wild boars entered pear orchards in Yunhe county in Lishui and chewed on branches and fruit, resulting in 100,000 yuans worth of damage.

Disruptive and sometimes deadly encounters between humans and wildlife are increasing worldwide. The Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) defines “human-wildlife conflict” as “when animals pose a direct and recurring threat to the livelihood or safety of people.” As they often cause humans to retaliate against and persecute the species, the SSC considers these conflicts to be “the most pressing threats to biodiversity conservation and achievement of sustainable development.”

Human-wildlife conflicts arise from various factors. For one thing, as numbers of wild prey species drop, carnivorous hunters may instead search for food among livestock. Urban sprawl, increase in human activity, and the consequent loss of animal habitats may also drive animals to come into contact with humans.

A notable example is the wandering herd of 14 elephants that migrated across Yunnan province over a 17-month period starting in spring of 2020—feasting on crops and going viral for drinking rice wine from household supplies en route. Experts suspected the herd set out in search of a new habitat. They caused over a million dollars worth of damage, according to state broadcaster CGTN, before finally returning to the jungles of southwestern Yunnan in late 2021.

In 2013, a TWOC investigation in Puer and Xishuangbanna in southwestern Yunnan found that in the last two decades, extensive cultivation of rubber, a resource-intensive but lucrative cash crop, has caused droughts and replaced swaths of rainforests in the region. This has led elephant herds to come down from the mountains to drink from rivers in the dry season, and seek nourishment in farmers sugarcane, banana, and corn crops.

Villages and farms have also cut off elephants traditional migration routes. “You cant simply tell the villagers they should protect the elephants…the elephants come and eat and trample their fields, leaving nothing for them to harvest,” Hua Ning, director of the International Fund for Animal Welfares (IFAW) elephant protection program based in Puer, told TWOC. “When our project first started, we asked the villagers if they disliked the elephants, and they said they hated their guts. Our strategy is to tend to human welfare before we protect the elephants.”

Counterintuitively, success in wildlife conservation might give rise to human-wildlife conflicts as well. In 1989, the Wild Animal Conservation Law was passed in China, which banned the hunting and killing of endangered animals as well as the sale of products made from them. The resulting reduction in poaching and rise in awareness of wildlife protection contributed to an increase of certain species, which subsequently led to more frequent encounters between wildlife and humans. In some areas, the recent decrease in human activity due to the Covid-19 pandemic has also encouraged wild animals to expand their range of activity.

How to ensure the safety of humans and that of wild animals at the same time is a tricky question. “[Human-wildlife conflicts] are in essence conflicts between stakeholders, and perhaps more accurately presented as ‘human-human conflicts,” says the SSC on its website on the issue. The competing stakeholders may be authorities and local people, professional conservationists and farmers, as well as people of different cultural backgrounds, all with different views on how and why to protect the ecosystem.

The Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park was established in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces in 2017 as a sanctuary for Siberian tigers and Amur leopards. With almost 100,000 human residents inside the park, the biggest number in any national park, its deputy director Zhang Shanning told China News in 2018 that “migration will only be considered when people and tigers are incompatible.” Residents on the forest farms within the park have been ordered to keep their cattle in pens for much of the year in order not to compete with deer, which tigers and leopards feed on, for grazing areas. If caught flouting these rules, they face a fine, yet the cost of buying industrial cattle feed is also high, and many are reportedly selling their livestock as they fail to make ends meet.

In the Sanjiangyuan region (the source of the Yangtze, Yellow, and Mekong rivers) in Qinghai province, snow leopards often prey on the livestock belonging to local Tibetan herders. To mitigate the conflicts, the Shan Shui Conservation Center, an environmental NGO, started a livestock insurance program in a village there in 2020. Yin Hang, a former employee of the project, tells TWOC that three snow leopards had been suffocated to death near the village that year after villagers threw burning cow dung into a cave in retaliation for a leopard attack on their livestock. Through the program, herders who have insured their cattle and sheep can receive compensation if their animals fall prey to snow leopards and other predators.

The organization has also invited the forestry bureau, local temples, and the community to discuss the details of the compensation scheme. “One important rule is that herders have to manage their livestock well,” Yin explains. For example, the stakeholders agreed only those herders who have actively taken preventative measures should receive compensation. To get compensation for yaks killed by snow leopards or wolves, villagers must also leave the carcasses in the wilderness as food for wild carnivores.

In Yunnan, the IFAW has tried to provide villagers with micro-loans and encourage them to plant things that elephants dont eat—tea, mushrooms, and oranges—so that they can have something left to sell if the elephants trample their corn crops. “It reduces the local resentment toward elephants,” said Hua in 2013. When TWOC visited, local forest police officer Chang Zongbo had suggested simply letting the elephants eat their fill, and having the local government compensate farmers for their loss using funds they receive for elephant conservation. Villagers told TWOC they hoped for better insurance schemes to cover their losses.

Buy-in from farmers and herders sometimes also runs up against local cultural beliefs. Yin says she frequently encounters questions from Tibetan herders who have lost sheep and cattle to snow leopards: “Why do you only protect snow leopards? Why dont you protect our sheep?” Over time, she has come to understand that because of the Buddhist belief that all life is equal, locals have a hard time accepting the “preferential” treatment of snow leopards.

She now often cites fellow Tibetan conservationist Kunga Tsangyang to explain their efforts: When a snow leopard kills a sheep, we must be on the side of the sheep, and when a human kills a snow leopard, we must be on the side of the snow leopard.

To make conservation efforts in Sanjiangyuan even more complicated, thousands of abandoned Tibetan Mastiffs now roam the prairies, a product of the “Tibetan Mastiff bubble” in the early 2000s that saw the dogs bred and sold for as high as 1 million yuan each, before the bubble burst. These stray dogs may compete with snow leopards and Himalayan vultures for food, attacking people and livestock, infecting local wildlife with diseases, or interbreeding with wild animals, further depopulating some endangered species. However, influenced by Buddhist beliefs, the majority of locals stand against hunting and killing the stray dogs.

Aware of the importance of local culture in conservation, in 2014 Yin founded her own NGO, Gangri Neichog, which is also dedicated to sustainable development in the Sanjiangyuan area. Gangri Neichog aims to study local solutions to environmental issues and explore the relationship between humans and nature from the point of view of Sanjiangyuans Tibetan population. “Biodiversity and cultural diversity are interrelated and complement each other,” says Yin. “There is profound ecological culture in the area where we work, including the taboo on harming animals or plants, or contaminating mountains and lakes that are considered sacred; and the belief that all life is equal. It is the locals respect and reverence of life that shaped a land where wild animals can roam free.”

To adapt conservation work to local attitudes, Gangri Neichog launched a program in collaboration with the government that invites experienced veterinarians to train local vets in sterilizing captured dogs, and works with temples to encourage locals to adopt sterilized, vaccinated, and dewormed Tibetan Mastiffs. According to Yin, over 700 stray dogs have been adopted through the program, and more than 70 local vets, including village vets trained with materials translated into Tibetan, continue to perform sterilization in the area.

Yin also points out that the human-nature interrelation is constantly in flux. For example, more and more locals have accepted the notion that snow leopards are an important, rare species and thus protected by the government.

“In the end, these animals are just following their instincts to survive,” says Yin. “‘Human-wildlife conflict is an imported term. I think what is more important is interaction and mutual adaptation,” she continues. “As humans change their way of life, so will the animals, and problems and challenges may arise in the meantime. The way to coexistence is to keep a safe distance between them.”

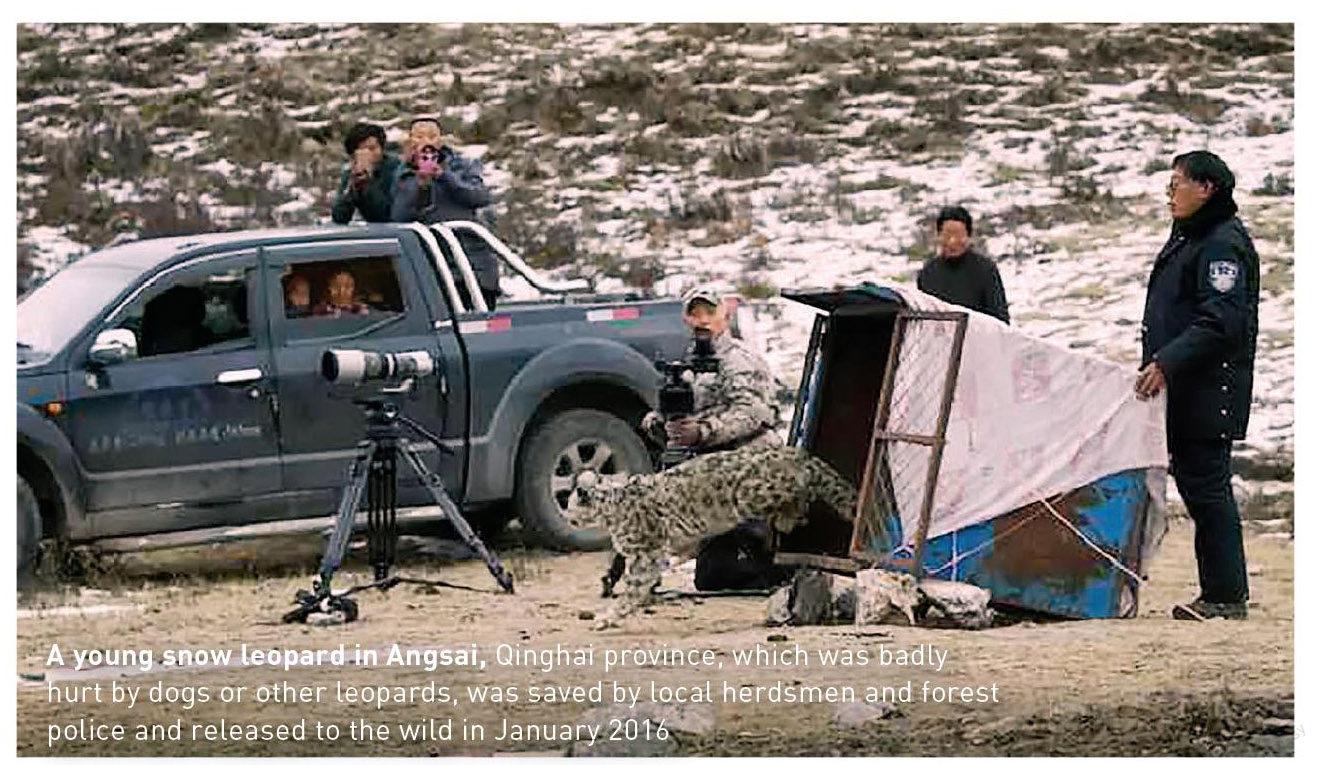

A young snow leopard in Angsai, Qinghai province, which was badly hurt by dogs or other leopards, was saved by local herdsmen and forest police and released to the wild in January 2016

The migrating herd of elephants roamed through farmlands of Yunnan last June