The Block-by-block Revival of an Ancient Chinese Building Techniqu

2022-05-30LiXiaoyang

Li Xiaoyang

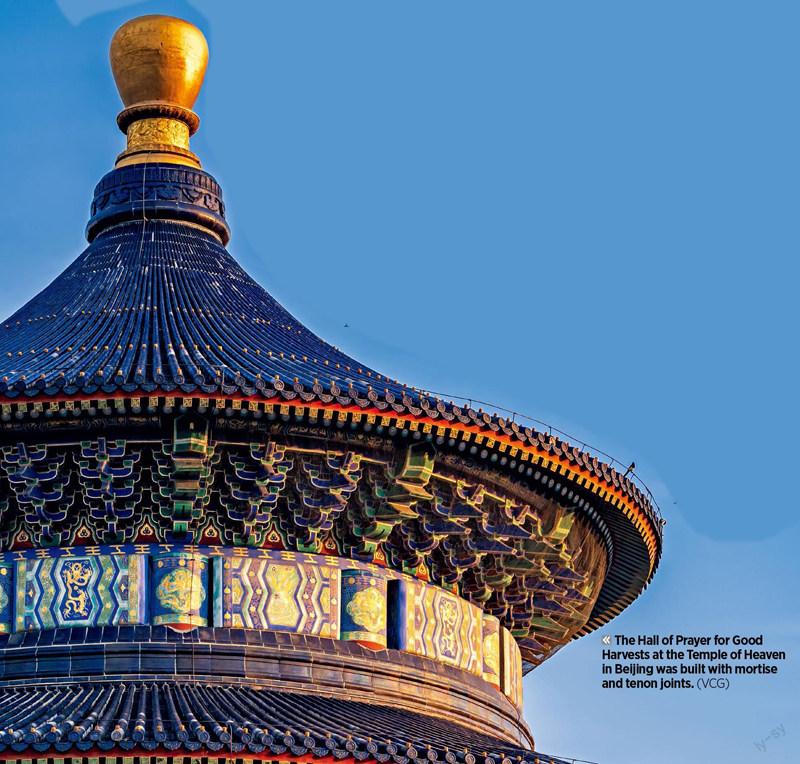

The Forbidden City, constructed over 600 years ago, served as the imperial palace of the Ming (1368- 1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Its woodenframed buildings, erected without nails or glue, have existed for hundreds of years and weathered several earthquakes. The secret lies in sun-mao, or the mortise and tenon technique, which is a concave-convex joint used to connect two sections of wood commonly applied in ancient Chinese architecture, furniture and other wooden instruments. The convex part is called the tenon (sun), and the concave part is called the mortise (mao). Mortise and tenon together create the dovetailed connection.

To revive mortise and tenon, 20-something Wang Ran has integrated the traditional building technique into toy blocks. In 2020, he became a co-founder of the mortise and tenon building block company Qiaohe based in Beijing. Its products range from ancient soldier figurines to toy tanks. The material used today is plastic, but the ancient method has been maintained.

According to Wang, he started learning the mortise and tenon technique from his mentor Liu Yansong, an inheritor of the technique, an Intangible Cultural Heritage item, in 2019. Aside from designing toy blocks, he would also give lectures at schools and colleges in Beijing to promote the culture.

“Mortise and tenon deliver a sense of traditional culture. Through toy blocks, the technique transcends time and race and passes on knowledge to later generations,” Wang told Beijing Review.

A Modern Makeover

Mortise and tenon got their name in the Song Dynasty (960-1279). During that era, the construction method was in the earliest stages and people were still unable to produce accurately convex parts. During the Song, people mainly used simple mortises that could be spliced to ensure a stable connection between articles, Wang said.

According to him, ancient architectural practices were quite precise. The details were clarified in books with illustrations to showcase different ways of construction. Every single detail, including how many craftsmen it requires, how long it will take, and what kind of craftsmanship it takes to create a small part, was specified. One notable work in the field is YingzaoFashi, or Building Standards, a Chinese technical manual on buildings compiled in the Song. It features many illustrations regulating the standards of materials and building techniques. In the Ming and Qing, the method matured, with an increasing application in furniture.

Recent years have seen the revival of traditional Chinese techniques, with masters of the mortise and tenon method appearing once again. As modern Chinese youth seek to entertain themselves in more diverse ways, the art toys of domestic brands like Pop Mart, Danish toy company Legos products, and a range of blind boxes, brand packages containing unknown products, have become popular. Many homegrown toy brands, such as building block brand Keeppley, have introduced Chinese-style products like ancient Chinese building models. It seems mortise and tenon toy blocks, too, bear some great market potential.

According to a reportreleased by Chinas e-commerce company JD.com in May, Chinas toy market was worth around77.9 billion yuan (US$11.5billion) in 2020, of which 16.2 percent were toy blocks.

To tap into surging marketdemand, Wang has merged his innovative ideas with ancientcraftsmanship. One of Qiaohes best-selling products is a series of toy soldiers produced incollaboration with the National Museum of China. The seriesincludes six toys of differentappearances, each representing a soldier of an imperial Chinese dynasty. Each set usuallyconsists of a dozen pieces.According to Wang, toy blockswith fewer pieces are easy forkids to play with.

Many consumers visitingQiaohes online store areparents, and the majoritycomment that their childrenare interested in the toys. Butpeople in their twenties, too, are buying the products—just forfun.

Many people refer to mortise and tenon toy blocks as“Chinas Lego”, but Wang thinks theyare two different concepts.According to him, Westernphilosophy focuses on pilingup the pieces. The new partsrelate to the original ones,which gradually grow biggerand bigger. By contrast, mortise and tenon building blocks arewithin a fixed frame, like a door, limiting their expansion.

Wang hopes the toy blockswill eventually become a prime example of Chinese art toys. “I want to use young peoplesideas and innovations to inject new vitality into mortise and tenon culture,”he said.

Master among Masses

Some of the methodsmasters have even built up an international reputation. Sixty-something master carpenterWang Dewen, commonlyknown as Grandpa Amu, isanother expert in the field ofmortise and tenon. Dubbed the “21st-Century Lu Ban,”a Chinese handcraft master who livedsome 2,500 years ago, he hasbrought the skills back to lifethrough diverse appliances and toys. His son, Wang Baocheng,started shooting videos of hisdad at work in 2018. The content captures his skills as well as the beautiful countryside scenery,gaining over 1.4 millionfollowers on YouTube.

Grandpa Amu has beenstudying the mortise and tenon technique since he was 13. In2017, he moved to GuangxiZhuang Autonomous Regiontogether with his sons family. Since then, he has crafted many wooden toys for his grandson,including a wooden Peppa Pig,an apple-shaped lock and a mini wooden robot that can walk. He is particularly skillful in making the Luban Stool, a foldable stool made from one piece of wood.

When it comes to woodenhandmade furniture, GrandpaAmu insists on carrying forward the time-honored techniqueand using traditional tools. Heis forever honing his craft.

His skills impressed manyoverseas viewers.“Utterlyamazing to watch how Grandpa Amu built this bridge. Doingit all with hand tools and zeropower equipment or glue ornails. This little bridge will bearound for all in this mansfamily to cherish and see thebeautiful job their Grandpa Amu has done. After watching this,I can see why it has so manyviews. Hats off to you, Grandpa Amu, and I hope your son andothers in your family will carryforward what they have learned from you,”a YouTube usersurnamed Norris commentedbelow one of the videos.

But Grandpa Amu noted that it is the traditional technique,not him, that has become anonline celebrity.“I hope to pass on the craftsmanship and better present Chinese culture,”hesaid.