Where Women Stand: Education and Work

2022-04-20LuoTongfang

Luo Tongfang

Females outnumber males in university enrollment in ASEAN countries. However, few of them get jobs and earn as much as their male counterparts

The strict dress code of universities of Thailand with males in dark shorts and females in dark belowthe-knee skirts makes the incoming flood of students a sight to behold. Thailand has seen advances in gender equality in education over the past two decades, as evidenced by the number of below-the-knee skirts creeping past that of pairs of shorts on campus.

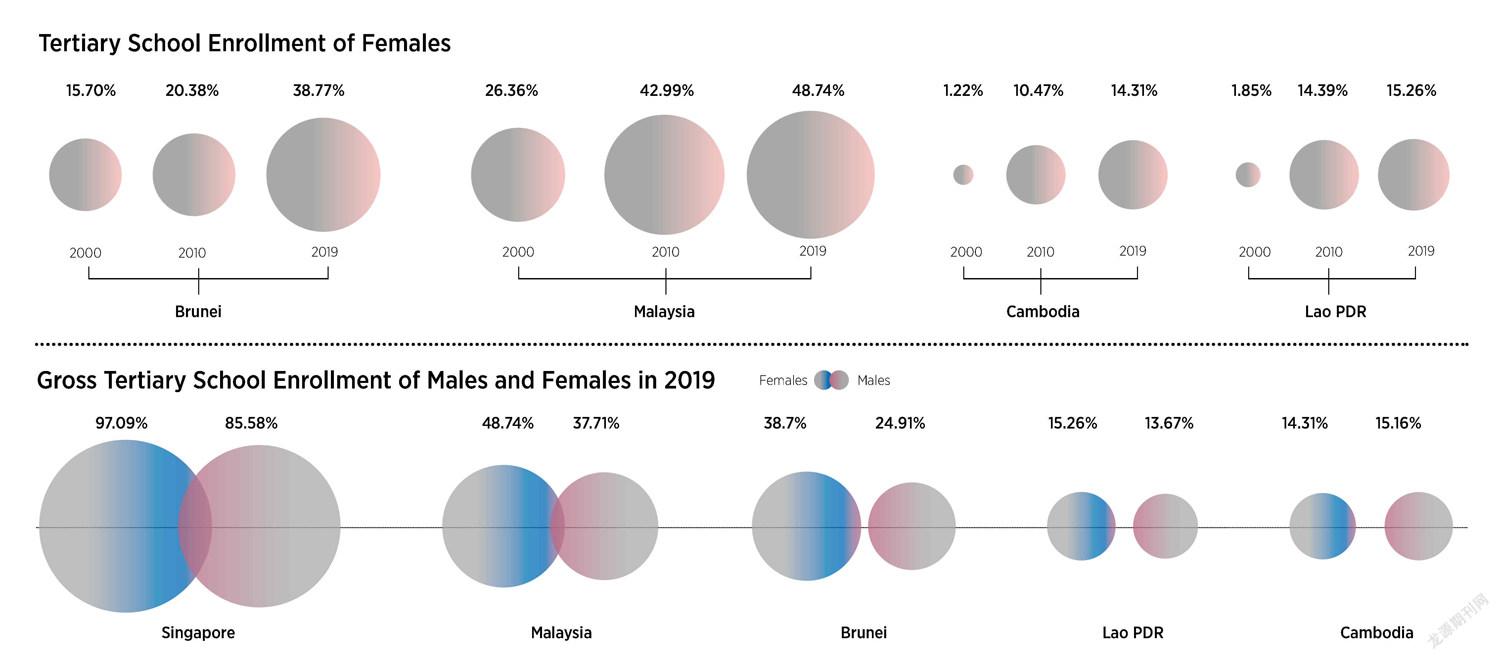

Alongside Thailand, increasing numbers of women are entering university campuses in other ASEAN countries, where the women’s higher education enrollmentrate has been increasing significantly. According to the latest data from the World Bank, the gross enrollment ratio for women in higher education reached 97.09 percent in Singapore in 2019,the highest among ASEAN countries. Even in Laos and Cambodia, where higher education enrollment rate has always been low, enrollment of women has increased about tenfold in the last 20 years.

Women Dominating Higher Education

According to the World Bank, in all of the ASEAN countries, with the exception of Cambodia, more women are enrolled in higher education than men. In 2019, female enrollment was more than 10 percent higher than male enrollment in some countries.

Some ASEAN universities have started to grapple with the imbalance of male and female students. RaudhahHirschmann, a Southeast Asian regional research expert at Statista, released a report titled “Students in public higher education institutions in Malaysia 2012-2019, by gender” in July 2021, which showed that in 2019, about 291,530 male students were enrolled in public higher education institutions as compared to about 415,020 female students, a staggering majority of more than 60 percent.

The higher college enrollment rate for women can be traced to gender imbalance in high school. SingkaRattanawalee is a first-year Thai graduate student at the Dalian Foreign Studies University. She recalled that 65 percent of her high school classmates were girls who all went on to pursue higher education. She said that her female classmates were more diligent and performed better academically than the boys and attended various extracurricular activities to help them stand out on college applications.

Dr. Malachi Edwin, dean of the School of Education at Taylor’s University, one of Malaysia’s oldest private universities, opined that many Thai boys do not think that university is a necessary pathto success. Many choose to enter the business world or get technician jobs, primarily for the sake of seeking social recognition. They pay less attention to university education than girls, causing their enrollment rate to stay relatively low.

However, women’s larger undergraduate enrollment doesn’t necessarily translate into advantages in further academic development. In ASEAN countries, the number of men holding a master’s degree gradually catches up with that of women and the number of male doctorate holders surpasses that of women.

Income Gap

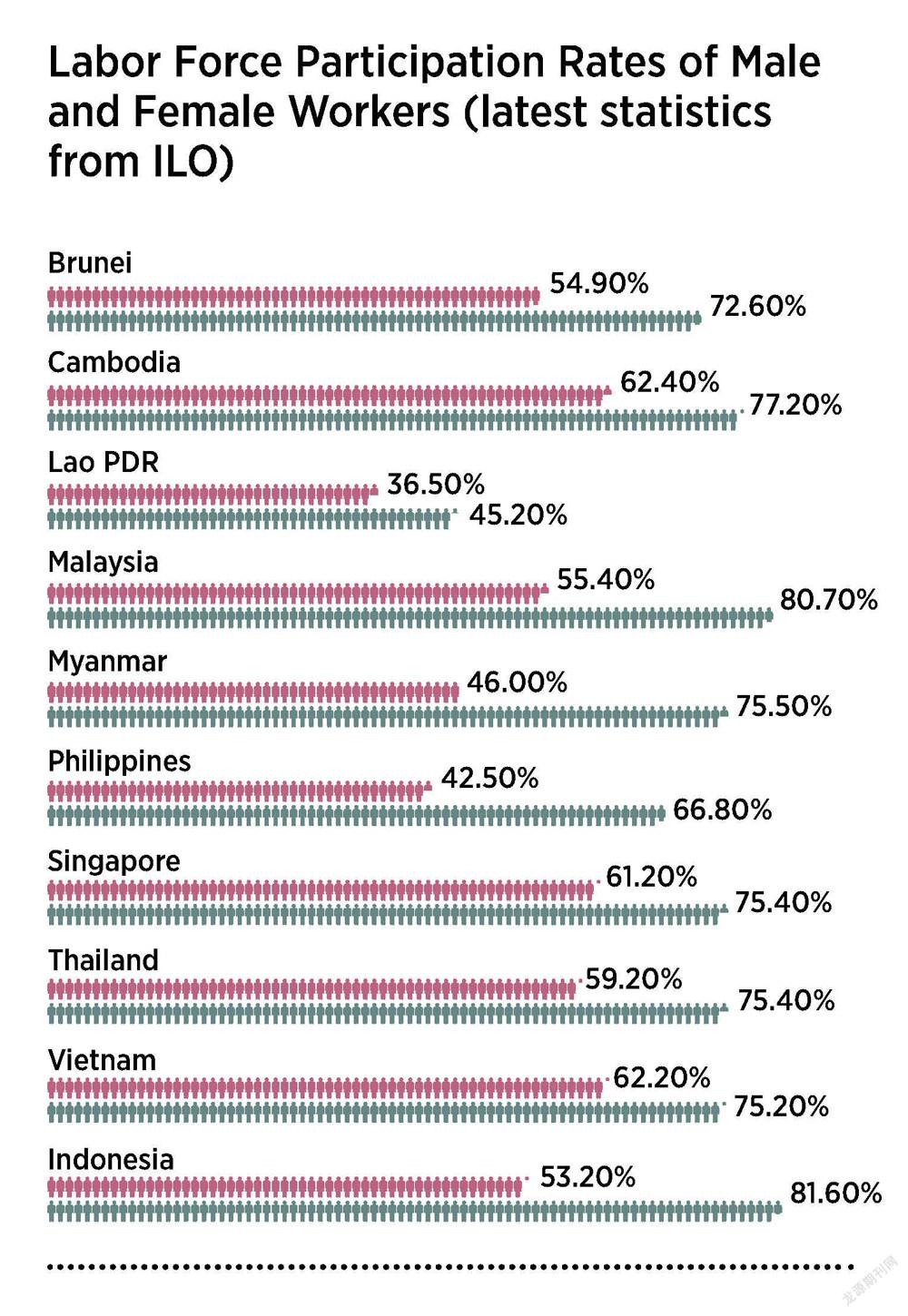

Data released by the International Labor Organization (ILO) has shown that ASEAN women’s path to the job market remains rocky even though more women complete higher education than men.

According to ILO’s most recent data, the average male labor force participation rate in the 10 ASEAN countries is about 19.21 percent higher than that of women.

Hirschmann also pointed out in her report that although there are more women than men in higher education in Malaysia, the labor participation rate of male university graduates is much higher than that of female graduates. Nearly half of women stopped working after marriage. “To meet the challenges of Industry 4.0, Malaysia cannot afford to lose the contribution of its increasingly highly-educated and highly-skilled women in the workforce,” she wrote.

In terms of income, only in Laos, Thailand, and the Philippines can women earn slightly more than men. In the countries where men earn more than women, the average monthly salary gap is much larger.

Women are more likely to work in industries that offer lower wages. The Asian Development Bank’s 2021 Women’s Economic Empowerment in Asia report noted a gender bias in Asian women’s employment. Its data showed that regularly employed Indonesian, Thai, and Vietnamese women mostly worked in manufacturing, education, and other basic industries and earned lower incomes than men. Trade data showed that the average monthly salary for the Thai manufacturing industry in the first quarter of 2021 was only 13,527.7 baht (US$407.22). In contrast, far fewer women were employed in science and technology, energy, real estate, and other industries that fetch higher income.

In addition, the ADB report regarded motherhood as a big reason for the low labor force participationrate of women. It referred to the impact of unpaid care work on women’s labor participation as a “motherhood penalty,” and pointed out that motherhood disrupts women’s participation in the labor market and reduces their working hours which in turn reduces their income with negative impact on promotion prospects. According to ILO’s Global Wage Report 2018/19—What lies behind gender pay gaps, parenthood is a major contributor to the unacceptably high gender pay gap.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdowns have increased women’s unpaid care work, and the “motherhood penalty” further reduced the return on women’s education. Serina Abdul Rahman, visiting fellow with the Malaysia Programme& Regional Economic Studies at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, delivered a speech titled “COVID-19 Impacts on Women in Malaysia” at the ADB Asian Women’s Economic Empowerment Virtual Policy Dialogue in August 2021. “In Malaysia, for example, women spend 64 percent more time than men on unpaid care work,” she said in the speech. “In other words, they are unpaid family workers.”

Although women in ASEAN countries with increasingly higher education have tried to break through the “glass ceiling,” achievements have not been significant enough. The Global Gender Gap Report 2021 (GGGR 2021) by the World Economic Forum analyzed data on women’s economic participation rate and economic opportunities in different countries and found out that in ASEAN, only Laos and the Philippines had more than 50 percent of women “legislators, senior officials, and managers,” while in other countries, the proportion was only around 25-35 percent.

Business Education vs. STEMWomen in ASEAN countries, especially Thailand, seem to perform better in companies or businesses. The GGGR 2021 showed that more than 60 percent of Thai companies appointed females to managerial and senior positions or had female majority ownership, and nearly 70 percent of Philippine companies had female majority ownership, the highest proportion in ASEAN. The same report indicated that women in ASEAN countries, such as Cambodia, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam, Malaysia, the Philippines and Laos, tend to major in business, administration and law at universities. In Cambodian universities, 63.67 percent of female students majored in “Business, Admin & Law,” the highest proportion in ASEAN.

The GGGR 2021 showed that STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), which is usually considered a weak point for females, was also very appealing to women in ASEAN countries. Bruneian universities’ STEM programs had the largest number of female enrollment, or 33.74 percent, in the country in 2018. In Singapore, Malaysia, and Myanmar, STEM subjects were the most popular major second only to business for female university students.

Although STEM is one of the most popular majors for women in Southeast Asia, the proportion of girls who major in STEM subjects is still much smaller than that of boys. STEM is the third most popular major among female university students in Thailand, but the proportion of girls majoring in STEM is still 29.28 percent lower than that of boys. Even in Brunei, which has the highest proportion of female STEM university students, the proportion was 14.86 percent lower than that of male students.

It is not surprising that fewer women in ASEAN countries are employed in the technology sector. In addition, a certain number of female STEM students turn to other sectors for employment, resulting in a more disadvantageous position for Southeast Asian women in the STEM sector.

Business education serving as an empowerment tool for women to make a mark in the business world indicates the huge potential of STEM education in boosting female participation in the science and technology sectors.

The key window for encouraging females to choose STEM subjects might be in adolescence. An April 2021 study by Ipsos Business Consulting showed that age 15 is critical for women to make the decision on whether to focus on STEM or not. The study examined views on STEM among young Singaporean students aged 16 to 25 and found that many female students who had considered STEM as a university major changed their minds during adolescence, mostly at the age of 15. The study referred to age 15 as “the window of opportunity” to keep girls interested in STEM. It recommended that positive influence be exerted on girls during their earlier adolescence through methods such as STEM project learning with the focus on peer collaboration and hands-on application to maintain their interest in STEM and enhance education in STEM career development.

杂志排行

中国东盟报道的其它文章

- Mainland Medical Experts Continue Inspection of Hong Kong’s Anti-COVID Work

- Lao Leader Speaks Highly of China-Laos Railway

- Chinese Foreign Minister Holds Discussion with Singaporean Counterpart

- Chinese-aided National Road Inaugurated in NE Cambodia

- Thai Health Authorities Approve Sinovac, Sinopharm Vaccines for Use in Children

- VOICES