An Empirical Study on the Relationship Between the Scale of International Students from ASEAN and China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment

2022-03-17YanJialiandCaiWenbo

Yan Jiali and Cai Wenbo

Shihezi University

Abstract: With the further development of economic globalization since the establishment of ties between China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 30 years ago and the continuous increase in the scale of international students in China, the training of international talents has become an important approach to avoiding the risks of transnational investments. We established panel data by selecting variables from the period 2006 to 2017, including the scale of international students coming from ASEAN to China, the gross amount of China’s outward foreign direct investment (OFDI), and the GDP per capita of ASEAN countries to further explore the correlations among these variables. We applied a panel-vector autoregressive (PVAR) model to conducting a Granger causality test, a Gaussian mixture model (GMM) regression analysis, a Monte Carlo-based impulse response analysis, and variance decomposition of the data. The results show that the growth of OFDI exerted an obvious positive impact on the inflow of international students from the countries along the Belt and Road (B&R) within a short period, the growth of the scale of international students coming from these countries to study in China had a strong positive effect on OFDI, the training of international talents was conducive to promoting the scale of transnational investments, but the overall quality was not very high, and its economic contribution rate was low. It is also found that OFDI and the scale of international students from the countries along the B&R promoted the GDP growth to a certain extent and the positive accumulation effect fluctuated due to external factors. Therefore, it is suggested to expanding the scale of OFDI and improving China’s core competitiveness in international student education. Intensive management of investment factors should also be conducted along with sound development of training mechanisms for international talents.

Keywords: ASEAN, scale of international students in China, GDP per capita, outward foreign direct investment

Research Background

The China-ASEAN community is a fundamental embodiment of the vision of “building a community with a shared future for mankind” in China’s neighboring countries. ASEAN countries are different from other countries along the B&R in that they have cultivated a community of ethnic origin with China due to the substantial number of Chinese immigrants moving southward. Therefore, they have closer economic ties with China and can even be regarded as a bridgehead of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. General Secretary Xi Jinping spoke highly of the bilateral relationship at the Special Summit to Commemorate the 30th Anniversary of China-ASEAN Dialogue Relations on November 22, 2021. He announced the establishment of the China-ASEAN comprehensive strategic partnership to build a peaceful, safe, secure, prosperous, beautiful, and amicable home together. This marked a pioneering initiative to develop amity and cooperation between China and its neighboring countries under the context of deepening economic globalization and profound changes in the international pattern.

The ten ASEAN member states are located between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean, adjacent to or separated from southern China by sea. Over the years, the implementation of China’s OFDI policies has exerted a synergizing effect on the integration of regional economics, trade agreements, and policies. During the period from the conclusion of the Investment Agreement on China-ASEAN Free Trade Area (CAFTA), from 2009 to 2017, China had an annual average outflow of US$9.343 billion and a stock of US$47.294 billion for direct investment in ASEAN, with annual growth rates of 38 percent and 32.96 percent respectively (Zhu & Sun, 2019). The Statistical Bulletin of China’s OFDI shows that the country’s investment flow to ASEAN reached US$10.28 billion in 2016, growing by nearly 64 times since 2005. It also states that China’s OFDI flow and stock in ASEAN were US$14.119 billion and US$89.014 billion, up by 41.2 percent and 27.46 percent respectively over 2016 (Fu & Wang, 2019). In the meantime, the Confucian culture has become a shared ideological core for Chinese and ASEAN cultures. Cross-border migrant populations, featuring a large size with the same origins but different destinations, have played a significant role in bringing talents to promote regional cooperation and have become a driving force, irreplaceable by other factors, such as politics and economics. International students from countries along the B&R, as the subjects of education service trade, play a unique and essential role in promoting trade development in Southeast Asia. The training of international students in China has also become an important approach to increasing returns on investments and facilitating coordinated regional development.

Literature Review

Concerning the analysis of correlations between OFDI and regional economic development of ASEAN, we found that Xiao and Liu (2017) studied the economic ties between China and ASEAN member states from temporal and spatial perspectives. The results show that China’s economic growth has a strong positive spillover effect on ASEAN countries, and the two sides are interdependent in space while the relations among ASEAN member states are competitive and complementary in terms of economic growth. In addition to boosting regional industrial economies, China’s OFDI is also aimed at enhancing the transformation of the reverse knowledge spillover effect and strengthening cooperation on resources. Lin, Tan & He (2019) studied the influence of China’s OFDI in ASEAN with the gravity equation and a Quantile model and found that in terms of the trade effects, there is significant spatial heterogeneity, and for the influence of OFDI outflow, there is a remarkable marginal effect, and China’s OFDI in ASEAN is mainly used for seeking resources. The types of international investments are determined by the interactions of multiple external and internal factors. By studying the efficiency and influencing factors of China’s OFDI in ASEAN countries, Fu & Wang (2019) found that the host country’s indicators, such as market scale, economic development level, trade openness, legal system, and government efficiency have a positive effect on the efficiency of China’s OFDI while spatial distance, stability and the status of democratic freedom of the host country impede the improvement in China’s investment efficiency. On the whole, opportunities and challenges coexist for economic exchanges between China and ASEAN. Bai (2019) analyzed the investment value of ASEAN and found that China’s OFDI in ASEAN features significant increases in direct investment quality, continuous expansion of investment fields, and large differences in the scale of OFDI in various member states of ASEAN. The findings also show some insufficiencies, such as a small scale and low industrial level of direct investments and a gradual decline in China’s gross investments in these countries in recent years.

Concerning the analysis of the characteristics of training international students in China and taking human capital as one of the core factors of economic development, we found that Kenneth J. Arrow (1962) put forward on the basis of economic externality theory of Alfred Marshall (1890) that external spillover of technologies can stimulate an economy so that stronger cultivation of international talents is not only a necessary foundation for coordinated regional economic development, but also an important approach to increasing the commodity exports of the host country and realizing the transformation of reverse knowledge spillover. The Study in China Program released in 2010 by the Ministry of Education of China set a goal of making the country the top destination of international students in Asia. In terms of the education of ASEAN students in China, the Chinese government also proposed the “Double 100,000 Plan,” which aimed to make the number of students coming to China or going to ASEAN both reach nearly 100,000 by 2020. Wang (2015) pointed out in his research that the education of international students in China is encountering bottleneck issues, such as the low proportion of students graduating from world-leading universities or with higher academic degrees, and the increase in the number of international students highly related to the major of the Chinese language and culture. After analyzing the features of higher education cooperation between China and ASEAN, Wang (2019) concluded that the cooperation on language teaching is characterized by equivalence while technological cooperation is unidirectional. She also found that the selection of cooperation partners is differentiated, and the cooperation process is mainly led by governments and implies competition among ASEAN member states. Although the educational system for international students from countries along the B&R has developed significantly, issues still exist, such as a low proportion of international students with higher academic degrees, the scale of students’ training limited to Chinese language and culture, and insufficiency in the level of international higher education.

Concerning the analysis of correlations between OFDI and the training of international students in China, the breakthrough for further developing bilateral trade of CAFTA lies in the exchanges of experience and know-how of regional higher education under the context of cooperation on international higher education. Yang (2012) summarized in his studies the foundation and achievements of China and ASEAN’s cooperation on higher education. He held that economic and trade cooperation had laid a good foundation for bilateral cooperation on higher education, and the two sides have reached a consensus on the global combined effect of higher education so that innovations in approaches and diversity of participants will continuously open new chapters for China and ASEAN’s cooperation on higher education. Jiang (2007) believed that if international students come to China mainly for the purpose of receiving short-term training, which is considered low-end education service trade output, then China would easily fall into the trap of comparative advantage, which means “an unfavorable position of a country in international trade due to structural defects arising from producing and exporting primary and labor-intensive products by fully depending on the comparative advantage of its natural conditions.”

Generally speaking, there is plenty of literature on China’s OFDI in ASEAN. Previous studies analyzed the status quo of China’s OFDI from many perspectives and provided a good theoretical basis for promoting sustainable development of OFDI, but most of the studies adopted the perspective of economics and analyzed factors, such as direct investment efficiency and return as well as trade facilitation while they did not pay much attention to the role of human capital. Moreover, there are few high-quality references that explore the educational development of international students from ASEAN and most of the studies take the internal development framework of higher education as the theoretical perspective and attach such keywords as educational resources, educational cooperation, and cultural exchanges as the objectives of their research. They seldom explored deeper reasons behind these students’ overseas study from the perspective of economic development demand, even though market demand is often one of the driving forces for human capital flow. In view of this situation, we related China’s OFDI in ASEAN to international students from these countries and delved into the push-pull effect behind high-caliber talent flow by analyzing external factors through a PVAR model. We sifted through how economic factors affect competition for human resources and proposed suggestions for further studies.

Research Design

Selection of Variables and Data Sources

On the premise of ensuring the completeness of data as much as possible, we selected the same span of years (2006 to 2017) and took the number of ASEAN students in China, China’s OFDI in ASEAN, and GDP per capita of ASEAN countries as research samples to establish a panel data.

The number of ASEAN students in China (st).

Lucas (1988) proposed in his human capital spillover model that worldwide economic externality is caused by human capital spillover. In recent years, the ten ASEAN member states, as one of the key sources of international students in China, have witnessed a growing trend of increase in the overall scale. Through an analysis based on Altbach’s push-pull theory, it can be observed that a student’s choice of the country for his or her overseas study is often the result of a struggle between the push and pull factors. Therefore, changes in the scale of international students can be regarded as a key indicator of the comprehensive strength of a country. To ensure data completeness, we took the numbers of ASEAN students in China from 2006 to 2017 as one of the variables. The data was mainly sourced fromConcise Statistics on International Students Studying in China.

China’s OFDI (in).

OFDI refers to an investor living in one economy, who controls or has a significant management influence on enterprise(s) located in another economy (Jiang, 2007). It not only acts like an important bridge for promoting scientific and technological exchanges among economies, but is also a key indicator affecting the labor markets and financial structures. Our study therefore took China’s OFDI in ASEAN from 2006 to 2017 as a variable. We sourced the data mainly from theStatistical Bulletin of China’s OFDI.

GDP per capita (gp).

GDP per capita is a crucial indicator for measuring regional economic levels. We used the price levels in 1990 as a benchmark and calculated the values of GDP per capita of ASEAN member states along the B&R through price index research methods. The data was mainly sourced from theInternational Statistical Yearbook. To avoid multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity that may arise in the analysis process, this study took the logarithm of the above variables respectively, aslnst,lnin, andlngp.

Modeling

Based on our literature review, we determined that previous studies on China’s OFDI delved more into such factors as basic conditions and openness of the host country that may affect OFDI growth by making a fixed-effects regression model. They seldom studied the external effects and results brought about by international students in China on free trade. Therefore, we established a PVAR model by using panel data (2006-2017) of the ten ASEAN member states as the research sample to further explore dynamic interactions between the scale of ASEAN students in China and OFDI, and GDP per capita of ASEAN during these years. It observed the impacts exerted by one variable upon another through GMM parameter estimates, Monte Carlo-based impulse response analysis, and variance decomposition of variables to clearly identify internal relations between human capital and OFDI in the globalization of free trade, and to offer theoretical reference to healthy and long-lasting development of bilateral relations on the premise of understanding the non-linear logic of influence between the two factors.

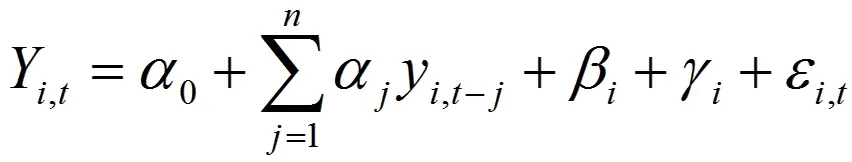

For the vector autoregression (VAR) model, variables were taken as endogenous, and an explanatory variable was set as the lag between the corresponding variable and other variables. The model uses a group of regression equations to explain the interactions among the variables. The VAR model was first proposed by Christopher A. Sims in 1980. Since it has a strict requirement on data length and risk of reducing the degrees of freedom of data and the accuracy of parameter estimations due to its requirements for the capacity and scale of parameters, it is often used for large time-series analyses. In 1988, Holtz-Eakin modified the VAR model by offsetting its downside, but keeping its practice of taking variables as endogenous to propose the PVAR model, which allows each sample to have different individual effects and a time effect on the cross-section. We set the dynamic model of relations among lnst, lnin, and lngp as follows:

In the above model: i stands for an ASEAN member state; t stands for an individual time span for observation; j stands for the lag order; βiand γtstand for individual fixed effect and time effect, respectively; εi,tis the stochastic disturbance of the model; Yi,tis the endogenous system generated from such variables as lnst (number of international students in China), lnin (China’s OFDI), and lngp (GDP per capita of ASEAN member states).

Data Analysis and Evaluation

Unit root test.

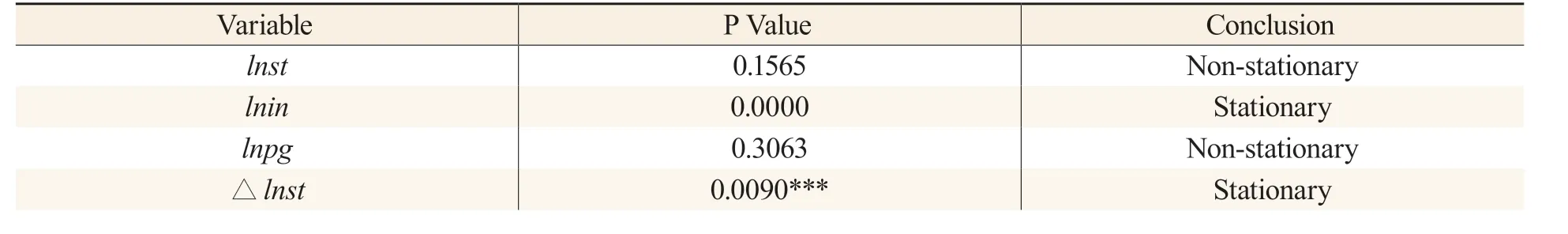

Data was analyzed and evaluated before an empirical analysis to enhance the reliability of the results. For this study, a well-established LLC method was used to conduct a unit root test of the data to avoid the occurrence of spurious regression and multicollinearity on the premise of ensuring data stationarity. The null hypothesis is that the series have a unit root and the test equation consists of a constant term and a trend term. See Table 1 for the analysis results.

Table 1 Results of the LLC-based Unit Root Test

Variable P Value Conclusion△ lnin 0.0000** Stationary△ lnpg 0.0190*** Stationary

The results show that the original serieslnstandlnpgfail the stationary test while the serieslninagrees with the null hypothesis at the level of 1percent. It was found by applying a first difference method to the data that △lnstand △lnpgreject the null hypothesis at the level of 1 percent and △lnpgproves that the series does not have a unit root at the level of 5 percent.

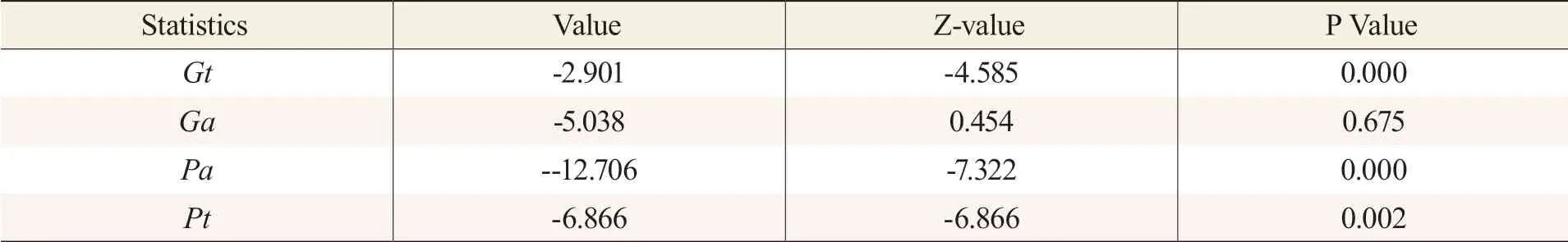

Cointegration test.

To avoid the occurrence of spurious regression, a cointegration test was conducted on the original sequence with a null hypothesis of “whether cointegration exists in the sequence.” A cointegration relationship expresses a stable and dynamic balance between two linear growth amounts, and more likely, the interactions among multiple economic aggregates featuring linear growth and dynamic equilibrium of their own evolution. A cointegration test can determine whether there is a long-run equilibrium among OFDI (in), the scale of ASEAN students in China (st), and the GDP per capita of ASEAN member states (pg). In the test results, as shown in Table 2,Gt,Ga,Pa, andPtare obtained by calculating the standard error based on the residual term of the model.Gt,Pa, andPtsignificantly reject the null hypothesis at the level above 1 percent, andGafails the test. Therefore, it is held in this paper that there is long-run stable cointegration betweenlnstandlnin.

Table 2 Results of the Cointegration Test

Determination of the lag order.

A VAR model can be made based on the completed cointegration test, but before this, an optimal lag term is a prerequisite to data validity. If the selected lag phase is too short, then it cannot well reflect the dynamic change of the model. If it is too long, then it may reduce the forecast effect of the model. Based on MBIC, MAIC, and MQIC, we determined the lag order of the model by adopting the principle of “the smaller the value, the more appropriate the lag order will be.” The results in Table 3 show that the original sequence data presents an ideal state with a first-order lag.

Table 3 Definitive Results of PVAR Model with Optimal Lag Phase

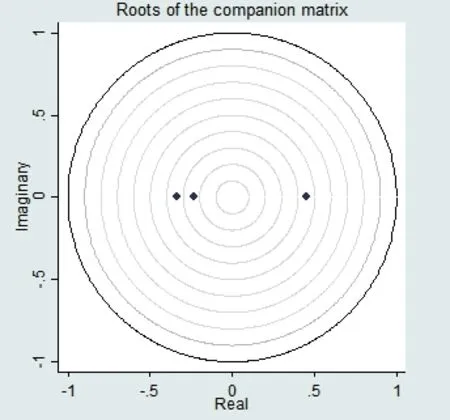

The unit circle test.

A robust model is a prerequisite to subsequent analysis, which often relies on observing the position of the root of a characteristic equation in a unit circle to estimate the stability of the model. The result is shown in Fig. 1. For the estimated model, all of the four roots of the AR characteristic polynomial lie in the unit circle, and their reciprocals (i.e., the root value) are all close to 0. It is therefore deemed that the estimated model is stable.

Figure 1. Positions of the Roots of the Characteristic Polynomial in a Unit Circle

Empirical Analysis

Granger Causality Test

The cointegration test results show that there is long-run and stable cointegration among OFDI (in), the scale of ASEAN students in China (st), and GDP per capita of ASEAN member states (pg), but they cannot prove whether there is causality between every two variables. Therefore, a Granger causality test was conducted to explore whether there is a causal relationship among the variables. The results are shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4 Results of the Granger Causality Test

For the Granger causality test, the null hypothesis is that there is no causality between X and Y. The above results show thatlnst→lnpg,lnin→lnst, andlnpg→lnstall reject the null hypothesis. This means thatlnst,lnin, andlnpgare respectively the cause oflnpg,lnst, andlnst.lnst→lnin,lnin→lnpg, andlnpg→lnindid not pass the test of significance. This means thatlnst,lnin, andlnpgare not Granger causality oflnin,lnpg, andlnin. It can be seen from the above that the scale of international students has a close causal relation with the host country’s economic development level, and OFDI is a significant impetus to increase the scale of international students in China.

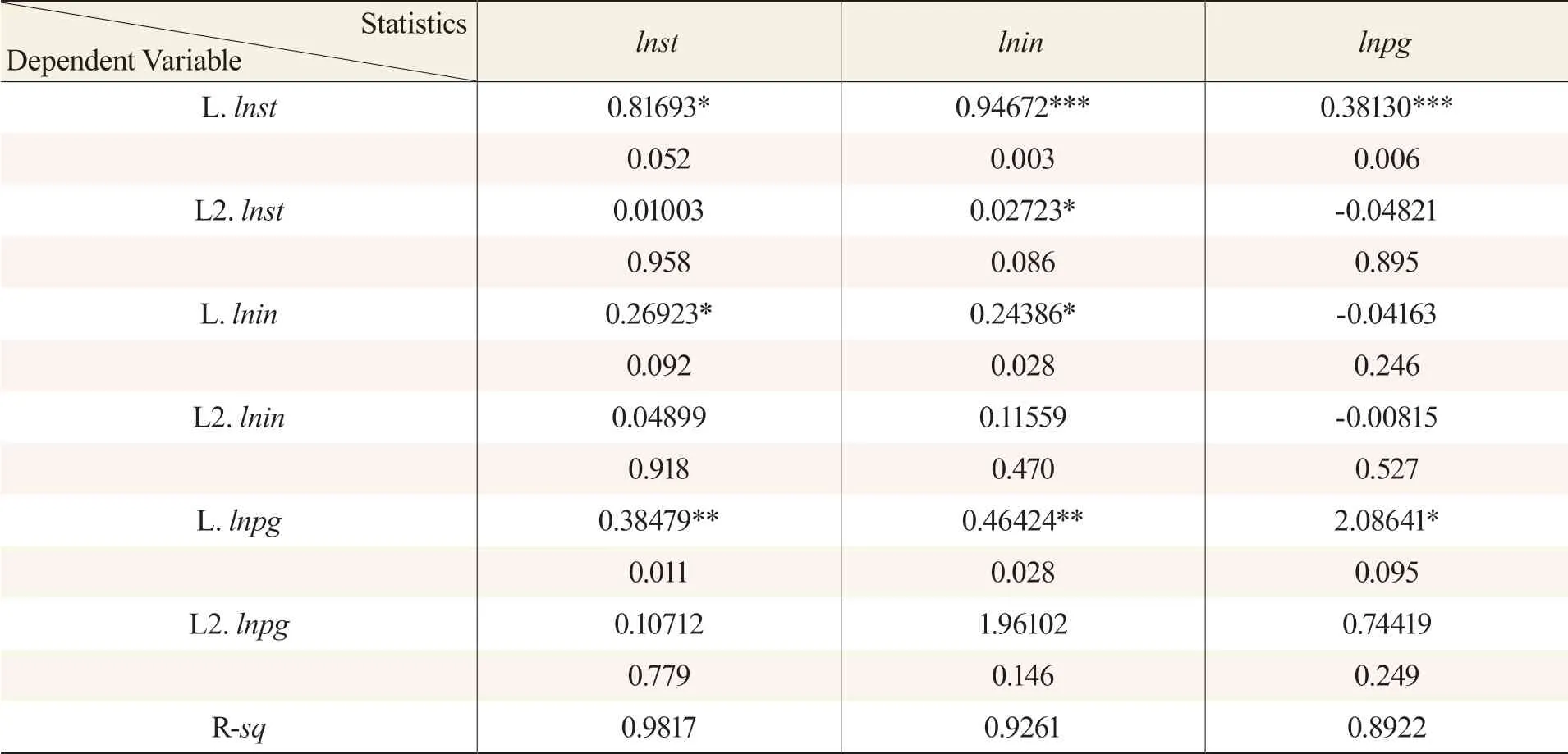

GMM Regression Analysis

Based on the causal relation identified among OFDI (in), the scale of ASEAN students in China (st), and GDP per capita of ASEAN member states (pg), the GMM method was applied in this study to obtain estimates of coefficients of the model. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5 GMM Estimates of the PVAE Model

The results show that with a lag of one phase,lnsthas a noticeable influence onlnst,lnin, andlnpg. The contribution coefficient oflnsttolninis 0.94672, and at the level of 1percent, it shows clearly that the scale of international students in China has significantly promoted a further increase in OFDI. The contribution coefficient oflnsttolnpgis 0.38130, smaller than that of it tolninandlnst. With a lag of two phases, onlylnst’s contribution tolninpassed the test of significance and the contribution coefficients oflnsttolnst,lnin, andlnpgdecreased somewhat. Especially, the coefficient of L2.lnstforlnstis -0.04821. The underlying reason may lie in the long periodicity of the return on human capital investment and the high instability and hysteretic nature of the return due to influences from many factors.

lninpullslnstandlninto a certain extent. It can be seen from the above table that the contribution coefficients oflnintolninandlnstare 0.38479 and 0.46424 respectively and significant at the levels of 10 percent and 5 percent, but the contribution level is still low and has much room for improvement. The contribution coefficient oflnintolnpgis -0.04163, mainly due to the reason that most of the ASEAN member states are underdeveloped or developing countries and their relatively poor infrastructure has lowered short-term return on OFDI considerably. For L2.lnst, it can be seen thatlnindoes not have enough subsequent power to promotelninandlnstwhile the contribution coefficient oflnintolnpgis -0.00815, which means that the negative effect is restrained somewhat, further proving the hysteretic nature of the return on OFDI.

lnpgis a significant Granger cause oflnst. In terms of GMM regression results,lnpgforlnstpassed the test at a 5 percent significance level with a contribution coefficient of 0.38479, while its contribution coefficients tolninandlnpgare 0.46424 and 2.08641, which are comparatively low. From the regression results of two phases, we can see that the contribution coefficients oflnpgtolnst,lnin, andlnpgare 0.10712, 0.9261, and 0.74419, respectively, mainly because countries in Southeast Asia are at different levels of economic development so that limited education resources and levels lowered the enthusiasm of international students coming to China from these countries. On the other hand, the scale of OFDI is mostly determined by gross national product (GNP). Although OFDI helps ASEAN member states develop their infrastructure, its return is not high, so that in the short term, it softens GDP growth.

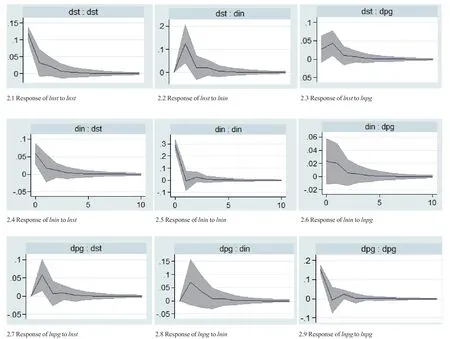

Monte Carlo-Based Impulse Response Analysis

Figure 2. Impulse Response Among the Number of ASEAN Students in China, China’s OFDI, and GDP Per Capita of ASEANNote: The horizontal ordinate indicates the number of traced lag phases of the impulse response function. The ordinate expresses the degree of response. The curve stands for the impulse response functions.

As the PVAR model is a kind of dynamic model and not built on the basis of an economic theory, it is difficult and insignificant to explain the estimate of a single parameter. In addition, the regression coefficient of an explanatory variable obtained only through GMM estimation cannot fully reflect the relations among each variable. Impulse response function, however, can reliably simulate the dynamic influence path by which a variable impacts another variable on the condition that other variables remain unchanged. On this basis, a Monte Carlo-based impulse response analysis was also conducted in this study, with the results as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3 express respectively the impulse responses of the number of ASEAN students in China tolnst,lnin, andlnpgwithin ten phases. It can be seen thatlnstimpacts itself greatly in the first two phases, but has little impact in the following phases. This demonstrates that for ASEAN students, they feature group activities for selecting the destination of their overseas study, but the subsequent pull effect is obviously inadequate after the short-term enthusiasm. The impact oflnstonlninrises quickly within one to two phases and drops after reaching its peak. In the third phase, it remains stable and its role in promoting decreases gradually.lnstpromoteslnpg, but the maximum limit of its impact effect is less than 0.05, representing a weak influence.

With the rise in the scale of OFDI, both the number of ASEAN students in China and the GDP of these countries grew as well. It can be seen from Fig. 2.4, 2.5, and 2.6 that in the short term, OFDI has an obvious impact onlnst,lnin, andlnpg. With additional phases, the value is close to 0. Especiallylnin’s impact on itself drops to 0 from its peak at a point near the first phase, showing that the impact effect of OFDI is weak and the subsequent investment scale is shrinking. All are related to investment cycles, expectations of return, and other influencing factors. In addition, the peak values of impact effects oflninonlnstandlnpgare 0.05 and 0.02 respectively, featuring a positive yet slight influence. The continuous growth of OFDI still relies on a direct increase in the OFDI amount.

The national economic level is one of the premises and key reference indices for expanding the scale of international students. We can see from Fig. 2.7 thatlnpghas an obvious impact onlnst, and the value drops after the third phase and becomes flat, showing a noticeable overall accumulation effect. In Fig. 2.8, the average impact effect oflnpgonlninis higher than that onlnst, mainly due to multiple non-linear influences between GDP and the scale of international students and the weakening of the impact effect by other factors. The GDP level is one of the direct forces for driving OFDI growth.lnpgcan drive the growth of itself as well. The impact oflnpgonlnpgin subsequent phases is volatile and cannot maintain a stable and long-run growth, as shown in Fig. 2.9.

Variance Decomposition

The next step of this study was to use variance decomposition to obtain the contribution rates of impact responses of different equations to the variance of each variable fluctuation. Through variance decomposition, the forecast variance of a variable within a system can be broken down to each disturbing term to obtain valuable information about the influence of each stochastic disturbance on variables in the model, as shown in Table 6 (Guo, 2013).

Table 6 Variance Decomposition of the Causality Relationships Among lnst, lnin, and lnpg

The results of variance decomposition in Table 6 show that, first, ASEAN students in China have a growing influence on transnational investment development while the influence on GDP growth suffers a dip due to the long cycle of talent dividend. In phase 1,lnst’s contribution rates tolnin,lnst, andlnpgare 19.73 percent, 80.27 percent, and 0, respectively. This indicates that the changes in the scale of international students in China are mainly due to a group effect. The scale has an indirect and small boost to OFDI growth while its contribution to GDP is not evident in phase 1, so there is a lag. With the increase of phases,lnst’s contribution tolninrises to 33.52 percent, whilelnst’s contribution tolngpgradually weakens in phase 10. Second, the growth of the gross amount of OFDI is a key foundation for driving OFDI. Therefore, in the above results, the contribution oflnintolnincontributes a substantial proportion. In phase 5, the contribution rates oflnintolnstandlnpggradually rise to 0.2508 and 0.1585. In phase 10, the contribution rates oflnintolnin,lnst, andlnpgare 0.4227, 0.3430, and 0.2343. This indicates that OFDI not only attracts international students to come to China, but also contributes to coordinated regional economic development. Third, GDP growth mainly depends on direct increases in GNP. In phase 1,lnpg’s contribution rate tolnpgis 0.9472 while its contribution rates tolninandlnstrise to 0.1232 and 0.1437, in phase 5 from 0.0217 and 0.0312, though the overall contribution is still low. GDP per capita is still the main factor for promoting regional economic development.

Conclusions and Suggestions

Based on the above analysis, we can conclude that rapid increases in China’s OFDI in ASEAN countries have provided more possibilities for further comprehensive cooperation between China and these countries. The training of transnational talents has a positive significance on the return of direct investments and national economic growth, but the interactions among OFDI (in), the scale of ASEAN students in China (st), and GDP per capita of ASEAN member states (pg) have obvious differences and a hysteretic nature. On this basis, we sifted through data concerning exchanges between ASEAN and China from 2006 to 2017 and used a PVAR model to explore and analyze the long-run dynamic relations among the three factors and made the following observations:

First, OFDI (in) and the scale of ASEAN students in China (st) significantly promote and depend on each other, but the overall accumulation effect is not strong. As most of the ASEAN countries feature underdeveloped infrastructure, China’s OFDI in these countries greatly offset the shortages in their industrial economy, while on the other hand, there are increased investment risks and a long cycle of investment returns. In the meantime, frequent international trade is bound to create huge development space for transnational talent markets and promote their development. The training of high-caliber talents can enhance the transformation efficiency of reverse knowledge spillover and boost the vigorous development of industrial economies. OFDI is highly relevant to the scale of ASEAN students in China. The results of this study show that OFDI plays a dominant role in the two factors and the investment characteristics of OFDI have a certain guiding effect on the flow of international students.

Second,in,st, andpgfeature a sharp increase in the pulling effect on themselves within the short term, but they all lack subsequent power and decline rapidly. Their pulling strength is shown aslnin>lnpg>lnst. ASEAN countries have noticeable regional advantages with China. The launch of the B&R Initiative has opened economic and trade markets between China and its neighboring countries. The establishment of CAFTA has especially pushed forward further development of OFDI through geographical advantages. The market immediately responded positively to this incentive at the first stage of OFDI, but due to restrictions from the economic levels of ASEAN countries and their return capacity, subsequent motivation for OFDI input is insufficient, and as the cycle of market returns is too long, most investors are taking a wait-and-see attitude. Meanwhile, China’s higher education for international students is still at its initial stage and developing rapidly. The training of international students generally focuses on humanities. The high-quality output of core technologies is still insufficient. This largely weakens its appeal and regional advantage to international students.

Third,in,st, andpgalso feature positive external influences, but they present an obvious lag in terms of overall timeliness. The level of funds support and transnational talent reserves are indispensable production factors.lnstandlninpromotelnpgsignificantly, but as talent dividends feature diversity and uncertainty, it cannot have a direct effect on economic growth in the short term and underdeveloped infrastructure also increases the cycle and risk of industrial profits. Currently, OFDI and the scale of international students in China show a certain positive effect accumulation, but they also have an obvious lag phase. Economic growth still relies on the pulling effect of the country itself. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously enlarge the input of OFDI and expand its scale. In the meantime, attention should be paid to improving education quality for international students and strengthening the training of technological talents. Regional economic development should be promoted in coordination with the development of human capital, while transnational investment risks should be effectively avoided to positively transform the reverse knowledge spillover effect.

Based on the above points, we put forward several suggestions for further development of the relations between the scale of ASEAN students in China and China’s OFDI as follows: (a) to expand the scale of OFDI and establish a sustainable management system. Infrastructure in ASEAN countries has become a bottleneck for their economic growth. If more funds can be invested in their infrastructure construction, then a favorable condition can be created for cross-border trade. A sustainable management system should also be established in line with the development features of CAFTA to guide the efficient and effective use of funds and lay a solid foundation for later investments. (b) enhance higher education levels to strengthen the core appeal to international students. The small proportion of highly educated international students is a key issue nowadays. As China does not have a complete training system for international students, it is not that attractive to highly educated international students, while foreign students without advanced degrees are generally attracted by preferential policies and not very strict requirements for graduation. Therefore, China’s higher education level for international students should be enhanced, and breakthroughs should be made to enable international students to conduct studies and make achievements in their interested fields. (c) establish a communication channel for talents and cultivate internationalized scientific research innovation teams. High-caliber talents in China should be encouraged to “go global,” and domestic and overseas academic and cultural exchanges should be strengthened to provide platforms for localized scientific research teams. The spirit of “learning from practice” should be advocated to strengthen the accumulation of tacit knowledge to enhance the absorption of spillover technologies in trade contacts and cultivate a wealth of high-quality international talents with core competitiveness. (4) manage investment factors in an intensive way and improve regulation mechanisms to enhance fund conversion rates. Quality, content, concentration, and combination types of investment factors should be regulated and adjusted to enhance returns. The reverse knowledge spillover effect should be used to adjust industrial structures, preoccupy the market and internalize advantages. Relevant preferential policies should be released to direct OFDI to highly sophisticated industries at a large scale. Financial advantages should be fully used to maximize the reverse spillover effect of technologies.

杂志排行

Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- A Comparative Study of Development and Reform of Urban-Rural Integration in Chengdu and Chongqing Based on System Theory

- Analysis of the Concept and Connotation of the New Economy and Reconstruction of Its Development Path: A Study Based on Chengdu’s Practices

- Research on the Collaborative Innovation Model in Regional Social Governance

- A Study of the Rain Classroom-Based Teaching Mode of College English for Art or Physical Education Majors

- The Legal Logic in the Practice of Poverty Reduction in Rural China in the One Hundred Years Since the Founding of the Communist Party of China

- A Study of the Life of Monk Dalang of the Early Qing Dynasty and His Contribution to Water Conservancy in Sichuan (Shu)