Is de novo membranous nephropathy suggestive of alloimmunity in renal transplantation? A case report

2022-03-05PrakashDarjiHimanshuPatelBhavyaDarjiAjaySharmaAhmedHalawa

Prakash I Darji, Himanshu A Patel, Bhavya P Darji, Ajay Sharma, Ahmed Halawa

Prakash I Darji, Himanshu A Patel, Department of Nephrology and Renal Transplantation, Zydus Hospitals, Ahmedabad 380059, Gujarat, India

Bhavya P Darji, Internship, Department of Medicine, GCS Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Ahmedabad 380025, Gujarat, India

Ajay Sharma, Ahmed Halawa, Faculty of Health and Life Science, Institute of Learning and Teaching, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 3BX, United Kingdom

Ajay Sharma, Consultant Transplant Surgeon, Royal Liverpool University Hospitals, Liverpool L7 8XP, United Kingdom

Ahmed Halawa, Department of Transplantation, Sheffield Teaching Hospitals, Sheffield S10 2JF, United Kingdom

Abstract BACKGROUND Post-transplant nephrotic syndrome (PTNS) in a renal allograft carries a 48% to 77% risk of graft failure at 5 years if proteinuria persists. PTNS can be due to either recurrence of native renal disease or de novo glomerular disease. Its prognosis depends upon the underlying pathophysiology. We describe a case of post-transplant membranous nephropathy (MN) that developed 3 mo after kidney transplant. The patient was properly evaluated for pathophysiology,which helped in the management of the case.CASE SUMMARY This 22-year-old patient had chronic pyelonephritis. He received a living donor kidney, and human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) mismatching was zero.PTNS was discovered at the follow-up visit 3 mo after the transplant. Graft histopathology was suggestive of MN. In the past antibody-mediated rejection(ABMR) might have been misinterpreted as de novo MN due to the lack of technologies available to make an accurate diagnosis. Some researchers have observed that HLA-DR is present on podocytes causing an anti-DR antibody deposition and development of de novo MN. They also reported poor prognosis in their series. Here, we excluded the secondary causes of MN. Immunohistochemistry was suggestive of IgG1 deposits that favoured the diagnosis of de novo MN. The patient responded well to an increase in the dose of tacrolimus and angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.CONCLUSION Exposure of hidden antigens on the podocytes in allografts may have led to subepithelial antibody deposition causing de novo MN.

Key Words: Post-transplant nephrotic syndrome; Recurrent membranous nephropathy;Secondary membranous nephropathy; Alloimmunity; Cryptic antigens; Case report

INTRODUCTION

The development of proteinuria after kidney transplantation is not uncommon, with 3% to 14% of recipients presenting with post-transplant nephrotic syndrome (PTNS).The risk of allograft loss with persistent proteinuria at 5 years is around 48% to 77%[1]. This may be due to either a recurrence or new (de novo) development of glomerular disease. It is rather difficult to differentiate between these two possibilities because only 15% to 20% of native kidneys are subjected to biopsy before transplantation[2].Factors, such as immunosuppression, donor specific anti-human leukocyte antigen(HLA) antibodies (DSA), acute rejection, hypertension and infection, might pose a diagnostic dilemma in regard to the clinical picture and histopathology of the graft.We hereby present a case of a kidney transplant patient who developed PTNS in the early period following transplantation.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

There were no chief complaints. Abnormal signs were observed at the 3-mo follow-up after renal transplantation.

History of present illness

A 22-year-old male patient was diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease due to chronic pyelonephritis and received dialysis for 8 mo. He received a live donor kidney transplant from his 42-year-old mother in August 2020. HLA-A, B and DR mismatches were 1-1-0. He was not given induction therapy and was maintained on triple immunosuppression (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and prednisolone). He was discharged on day 7 with a serum creatinine of 0.9 mg/dL (normal: 0.7-1.2 mg/dL).His graft duplex scan was normal, and tacrolimus 12-h trough level was maintained at 10 ng/mL. At the time of discharge, his urine protein was normal. At the 3-mo followup, he had signs of mild pedal oedema.

History of past illness

The patient had a history of end-stage kidney disease due to chronic pyelonephritis treated with a renal transplantation 3 mo prior. A bilateral ureteric re-implantation for vesicoureteral reflux had been performed at the age of 6 years.

Personal and family history

No significant personal and family history.

Physical examination

We observed mild pedal oedema, which was pitting in nature.

Laboratory examinations

His urine showed + 4 proteinuria, and urine protein/creatinine ratio was 4.6 mg/mg(normal: < 0.2 mg/mg) with stable serum creatinine. We recorded a serum albumin level of 3 gm/dL and total cholesterol of 295 mg/dL, suggestive of PTNS.

Imaging examinations

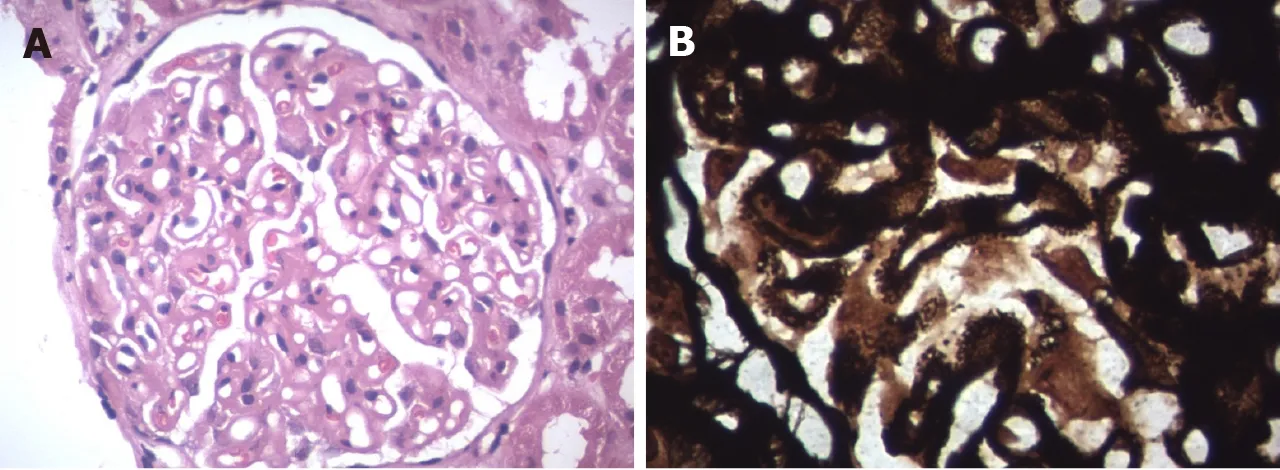

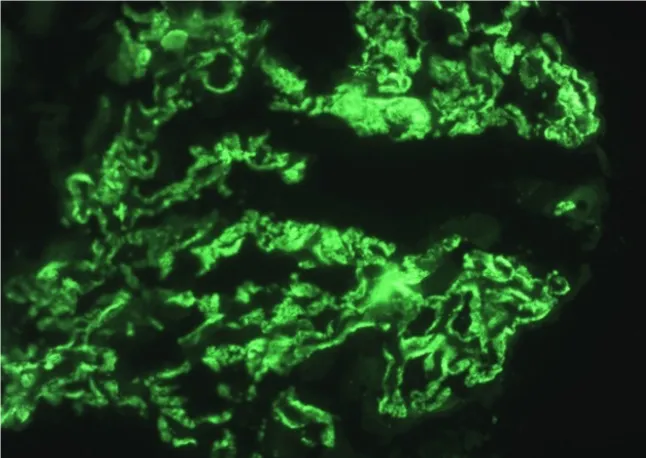

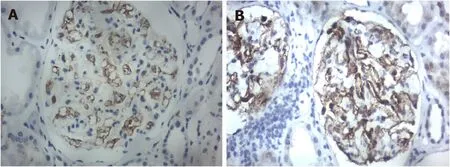

Allograft biopsy was performed and subjected to light, immunofluorescence and electron microscopy to rule out secondary causes of PTNS. Light microscopy revealed a thickening of the basement membrane and spikes at high power magnification with periodic acid-Schiff silver methenamine stain (Figures 1A and 1B). Immunofluorescence microscopy showed IgG deposits along the glomerular basement membrane in a granular pattern (Figure 2), suggesting membranous nephropathy (MN).

Figure 1 Light microscopy. A: Haematoxylin and eosin staining (40 × magnification) showed diffuse thickening of the glomerular basement membrane; B:Periodic acid-Schiff silver methenamine stain (100 × magnification) showed membrane thickening.

Figure 2 Immunofluorescence microscopy showed granular IgG deposits in the glomerular basement membrane.

EVALUATION AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

This was a case of PTNS that was histologically suggestive of MN. We conducted further investigations to identify secondary causes of MN, antibody-mediated rejection(ABMR), and differentiation of recurrencevs de novoMN.

This patient’s serology was negative for hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus and hepatitis E virus. Cytomegalovirus was also undetected by polymerase chain reaction.Antiphospholipase A2 receptor antibody testing was negative. There was no evidence of post-transplant malignancy upon clinical assessment and detailed investigations.Secondary causes of MN were ruled out.

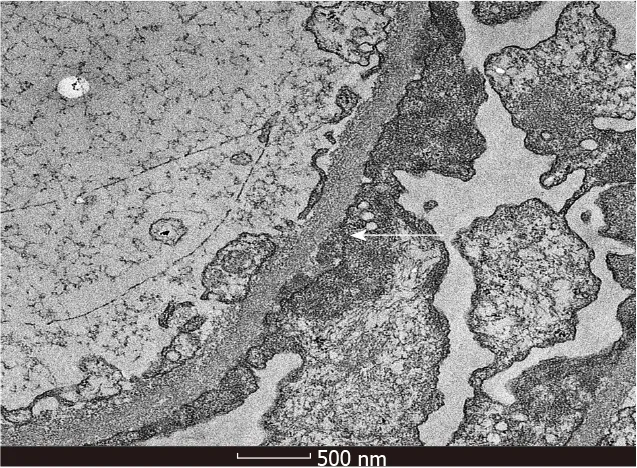

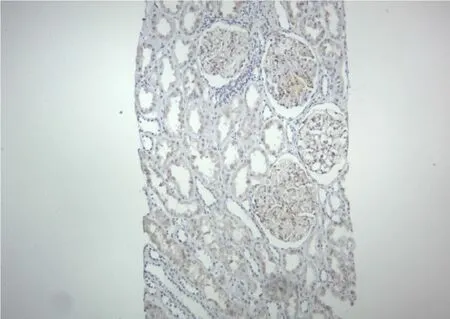

In this recipient, the donor class II HLA was fully matched. When he developed proteinuria, DSA was negative. His biopsy did not show any changes of ABMR.Electron microscopy did not show duplication of peritubular capillaries or glomerular basement membrane (Figure 3). The C4d stain was also negative (Figure 4). These findings ruled out ABMR in our case.

Figure 3 Electron microscopy showed subepithelial electron dense deposits (× 13500).

Figure 4 Immunohistochemistry (10 × magnification) was negative for C4d stain.

The biopsy revealed positive IgG1 deposits and scarcity of IgG4 after immunohistochemistry (Figures 5A and 5B).

Figure 5 Immunohistochemistry staining (40 × magnification). A: IgG4 was negative; B: IgG1 was positive.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Post kidney transplantde novoMN.

TREATMENT

The patient’s tacrolimus 12-h trough level at the time of development of PTNS was 5.9 ng/mL. The dose of tacrolimus was increased to achieve a level of 9-12 ng/mL.Ramipril was commenced and optimized to 5 mg twice a day. Serum creatinine and potassium were checked on day 10 and remained unchanged. The dose of ramipril was kept tolerable to avoid hypotension.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At 6 mo after the biopsy, his urine protein creatinine ratio decreased to 0.6 mg/mg.His graft function remained stable with a serum creatinine level of 0.94 mg/dL.

DISCUSSION

Recurrence of idiopathic MN after renal transplant is seen in 25%-40% of cases. A diagnosis ofde novoMN is reported in 1%-2% of post-transplant adults and up to 9%in paediatric renal transplant recipients[3]. The exact incidence is difficult to ascertain due to variability in pretransplant biopsies to confirm diagnosis[2,4].

New onset hepatitis virus infection, particularly hepatitis C virus and hepatitis B virus, is a common secondary cause ofde novoMN[2,3,5]. Tatonet al[5] reported a probable association of hepatitis E virus infection with post renal transplantde novoMN. Teixeiraet al[6] reported a case of cytomegalovirus infection and its relationship tode novoMN. Risk factors such as post-transplant malignancy, ureteral obstruction and renal infarction have also been found to causede novoMN[2]. Prasadet al[7]reported a case ofde novoMN in a patient having Alport’s syndrome as a native kidney disease. It has been reported thatde novoMN is more common in patients with IgA nephropathy[2,3,7]. We ruled out all the secondary causes of MN in our patient.

Sometimes, a recurrence of MN may be misdiagnosed asde novoMN due to undiagnosed native kidney disease[2,4]. Pathology findings ofde novoMN are like those of idiopathic MN, except for mesangial proliferation, focal and segmental distribution of subepithelial deposits, and simultaneous presence of different stages of disease inde novoMN[3]. Anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibodies have been identified in most cases of idiopathic MN, whereas anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibodies are absent inde novoMN because of other causative antigens that remain unidentified[2,3,8-10]. Different IgG subtype depositions have been reported in cases of primary/recurrent MN andde novoMN. IgG4 was commonly deposited in recurrent MN, whereas IgG1 was observed inde novoMN. In our case, there was an absence of anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibodies and IgG1 deposition in the kidney biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis ofde novoMN.

Schwarzet al[11] published a retrospective observational study of renal transplant subjects transplanted between 1970 and 1992 who developedde novoMN. They observed histopathological features of acute vascular rejection in 17 out of 21 recipients and interstitial rejection in 12 out of 21 recipients. During this period, the availability of DSA measurement techniques and knowledge of diagnosing ABMR may have been limited. Other investigators have reported a possible relationship of donor-specific alloantibodies in the development ofde novoMN[12]. Wenet al[13]reported the presence of HLA-DR on podocytes of recipients who developedde novoMN; they also reported a higher incidence of peritubular capillaritis, intimal arteritis and C4d deposits in post-transplant MN in comparison to recurrence of idiopathic MN in the renal allograft. There are also reports of poor prognoses in patients who hadde novoMN possibly related to ABMR[11,12]. Interestingly, Bansalet al[14] reported a case ofde novoMN following a renal transplant between conjoined twins. Even in our case, the mother was the donor, with fully matching HLA-DR. The biopsy of our patient confirmed that there were no changes suggestive of acute or chronic ABMR.

There may be another pathophysiological mechanism precipitating in the development ofde novoMN. It is likely that immunological, viral, mechanical or ischemic injury to the graft may expose the podocyte cryptic antigens to the recipient immune system. This may trigger an activation of innate immunity, resulting in production of auto- or alloantibodies against the antigens on the podocyte. This antigen-antibody complex develops at subepithelial sites and causes activation of complement and membrane injury[9].

There is lack of consensus in the published literature about the optimal management ofde novoMN. Schwarzet al[11] reported no response to methylprednisolone bolus and a high graft loss. El Kossiet al[12] hypothesized thatde novoMN was an atypical manifestation of ABMR. If a secondary cause, such as viral infection or malignancy, is identified, then the treatment of the underlying cause might treat MN. Cyclophosphamide or rituximab has been tried, as in the treatment of idiopathic MN[8]. In our case, we optimized the dose of tacrolimus and started an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; the proteinuria was significantly reduced, and graft function was stable after 6 mo, suggesting a good prognosis.

CONCLUSION

De novoMN, a rare disease in renal allografts, may be due to exposure of a hidden antigen on the podocytes that is recognized by the immune system of the recipient.The causative antigens still need to be identified. The reported poor prognosis ofde novoMN may be due to misdiagnosed ABMR, as it was in an era prior to routine availability of DSA by the Luminex platform (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA,United States) and recognition of C4d for an ABMR diagnosis. Proper evaluation and targeting of the pathophysiological processes may help in the management of these patients.