Request-Granting-Resistance Sequence in Chinese Public Service Calls

2022-01-15LiLi

Li Li

Dalian University of Technology, China

Abstract This study draws on a database of 200 citizens’ telephone calls to a Chinese radio program phone-in helpline and uses conversation analysis as the methodology to examine citizens’requests for assistance, officials’ granting responses to citizens’ requests, citizens’ or the host’s resistance to officials’ granting responses. It is found that citizens make complaints about their previous failure to solve their problems in a way that is not merely to legitimize their current requests for assistance but also to ask for an account of their previous failure to have matters satisfactorily resolved, since in many cases even when officials grant citizens’ requests, the granting is followed by those citizens’ pursuit of reasons for or remedy to their previous failed resolution attempts. The study also analyzed how citizens’resistance to officials’ responses is handled and how the final agreement is reached. The findings of this study contribute to the study of turn design of requests and preference organization of responses to requests and have implications for responses to requests in service encounters.

Keywords: requests, complaints, granting responses, resistance, Chinese public service calls, conversation analysis

1. Introduction

Making a request for information, service or assistance is a ubiquitous social action.The earliest study of request is the speech act theory proposed by Austin (1962). Then Searle (1969) proposed the concept of felicity condition to analyze what constitutes a speech act. These studies were conducted based on invented and isolated utterances and did not examine what actually occurs in naturally occurring conversation. Since the 1980s, a large number of scholars have applied politeness theory (Brown &Levinson, 1978, 1987) and collected data using a discourse completion test or roleplay to examine request strategies in indigenous languages (e.g., Shahrokhi, 2012;Zhang, Shin & Rue, 2007) or compared politeness strategies in two or more languages(e.g., Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, 1984; Chen, He & Hu, 2013; Lee, 2005; Vacsi, 2011).Request strategies were found to be closely related to the social identities of language users. However, Curl and Drew (2008) recorded people’s natural conversations,examined request forms in them and found that different request forms might be used by the same speaker in different sequential contexts. This finding is different from the findings of previous studies that used data collected from a discourse completion test or role-play. In other words, previous studies based on fabricated cases could not discover how requests are actually made in people’s conversation.

Due to the limitations of these previous studies, in recent years, a growing number of studies have been conducted to examine requests in naturally occurring conversation.Requests are examined as initial actions of asking for information or assistance, and the initiation of requests makes responses to them relevant (Schegloff, 2007). Conversation analysts have explored how requests are normally initiated, what occurs between requests and responses, what responses to requests are delivered and consequences of various responses. They have examined request and response in ordinary talk (Aronsson& Cekaite, 2011; Craven & Potter, 2010; Goodwin & Cekaite, 2013; Kent, 2012) and in helplines such as emergency calls (Raymond & Zimmerman 2016; Rønneberg &Svennevig, 2010; Zimmerman, 1992), commercial service calls (Kevoe-Feldman,2015; Kevoe-Feldman & Robinson, 2012; Lee, 2006) and after-hour calls to doctors(Drew, 2006). Nevertheless, there have been few studies of request and response in nonemergency public service calls, especially in a Chinese context.

In the majority of previous studies, preferred responses, in which requests are granted, tend to be accepted and lead to sequence closure, while dispreferred responses,in which requests are not granted, are normally accompanied by accounts for refusal or followed by further questions (see also Schegloff, 2007). This study examines citizens’requests and officials’ responses in a Chinese public helpline and focuses on cases in which officials’ grantings of citizens’ requests are followed by resistance, such as solicitations and concerns about whether requests will actually be granted in the future,and argues herein that this could be closely related with the turn design of requests and the institutional setting in which requests and responses are made.

2. Data and Method

The data used in this study are audio recordings of 200 citizens’ telephone calls to a Chinese radio phone-in program at FM105.8 MHz. They were collected from the official website of the program (http://www.ijntv.cn/zwrx/) in 2016-2018. Since this is a live broadcast program, the recorded telephone calls are naturally occurring conversation. The program airs from 08:00 a.m. to 08:40 a.m. on weekdays. When citizens meet troubles, they can dial a specific telephone number to contact the program and report the problems they encountered. Most citizens contact this helpline only after they failed to get solutions to their problems from public service agencies by following a routine procedure. Every weekday, officials from one or two government agencies or schools or state-owned companies are invited as program guests to respond to citizens’ inquiries or requests. The host of this program provides guidance for citizens and officials. Every Saturday, this program reports to the audience how citizens’ problems have actually been solved. This helpline is characterized by its dual institutional task: it is intended to solve citizens’ problems and to oversee public service agencies’ daily operations.

Recorded telephone calls were transcribed following Gail Jefferson’s transcription system (Atkinson & Heritage, 1984). Personal identifiable information, such as citizens’ names and addresses, was coded in double parentheses to protect their privacy. Because of limited space, only the original and translated versions of extracts are provided herein and the word-for-word translation is omitted.

The methodology used in this study is conversation analysis (CA). Turns at talk are examined in terms of what actions are performed and how they are accomplished.Talk at a turn displays its speaker’s understanding of the prior turn and at the same time it forms the context to which the next turn responds. “The relationship of adjacency or ‘nextness’ between turns is central to the ways in which talk-ininteraction is organized and understood” (Schegloff, 2007, p. 15). An adjacent pair of actions, such as request and response, is the minimal form of a sequence. The occurrence of an initial action makes a type-fitted response to it relevant and the response displays its speaker’s understanding of the prior turn. Participants’ responses to prior turns are commonly used analytical resources for conversation analysts to validate their understandings of actions performed in the prior turns. “Within CA,every effort is made to ground any analysis in the understanding and orientations of the participants themselves” (Clayman & Heritage, 2002, p. 19). In the present study,citizens’ or the host’s resistance to officials’ granting responses is examined to find out problems within their responses and to discover how they could communicate with callers more effectively.

3. Citizens’ Requests

When citizens contact the public service helpline, most of them report their problems and complain about their failure to get solutions from public service agencies as a way of assistance recruitment (Kendrick & Drew, 2016). Since there is accountability in asking for help in cases in which it is not obvious that requesters are unable to solve their problems themselves, one account for citizens’ requests is their failed selfhelp and contacting public helplines is regarded as the last resort (Edwards & Stokoe,2007). This is illustrated in Extract 1. Mr. Qi, The commissioner of a district of Jinan(which is the capital city of Shandong Province in China) is invited to the program.

In Extract 1, the caller reports a public problem as an ordinary citizen. He reports the bad road condition and uses the extreme case formulations (Pomerantz, 1986)“太” (“terribly”) and “全” (“full of”) to emphasize the severity of the problem.In this way, he indicates that this problem causes inconvenience for citizens. The end of the caller’s talk at line 4 could be an ending point of his request, because his identity, address and his problem have been reported. However, the host delivers a continuer at line 5, expecting more information. At line 6, the caller describes his repeated yet failed attempts to approach the agency in charge of road maintenance as a way to legitimize his request for assistance from the helpline. Although this is a transition-relevant place and there is a short silence of 0.3 second, the host does not take the turn. Then at line 7 the caller makes an explicit request for a solution as a way of indicating an end of his request for assistance. This extract indicates that not only the caller’s report of his problem but also his complaint about previous failed attempts are regarded as essential components of his request for assistance.

The following example is also a citizen’s report of a public problem. The caller describes the transgression (Drew, 1998) he has seen and his recurrent failure to solve it in a routine way, without an explicit request. The caller indicates that the reported problem was an obvious violation of the relevant regulation and that it was the obligation of the agency in charge to attend to it in time. Therefore, the caller’s report of the long existing problem and the relevant agency’s failure to solve it could be a legitimate request for a public intervention. This is illustrated in Extract 2. Mr. Zhao,the commissioner of a district of Jinan, is invited to the program.

In Extract 2, the caller prefaces his reported problem with a statement of its nature, i.e., violation of the regulations on roadside stall business. The caller uses the word “咱们” (“exclusive we”) to indicate that he is reporting this problem on behalf of the community. At line 6, the caller describes that he has seen “好多这个摊位”(“many booths”) and “在这个主道上” (“on the main street”) to show his primary access to the problem and the severity of it. This is a possible end of the caller’s turn,because at this point the caller’s talk is grammatically and pragmatically complete and with a falling tone. Also, at this point, there is a long silence of 1.5 second. However,at this moment there is not any feedback from the host, which indicates that more relevant information is expected.

Then at line 7 and line 9, the caller states that he has tried, to no avail, to ask to have this problem solved for over one month by following the routine practice of problem reporting but he has not succeeded in getting the attention of the administrative agency. These statements further legitimize his request for assistance.“12345” mentioned by the caller is a public helpline set up by the government.Citizens could dial the telephone number 12345 to report their problems if they meet troubles. Operators handling this helpline record citizens’ legitimate requests and convey them to relevant service agencies (e.g., the urban-management bureau in this extract). Relevant service agencies are required to work out solutions to citizens’problems within a limited time. At line 10, the host asks a question about whether the relevant agency gave the caller a reply about the reported problem, which conforms to the supervisory role of this helpline. It could be easily observed from this extract that not merely the reported problem but also how it has been dealt with by the relevant agency are regarded as essential components of the caller’s request for assistance.

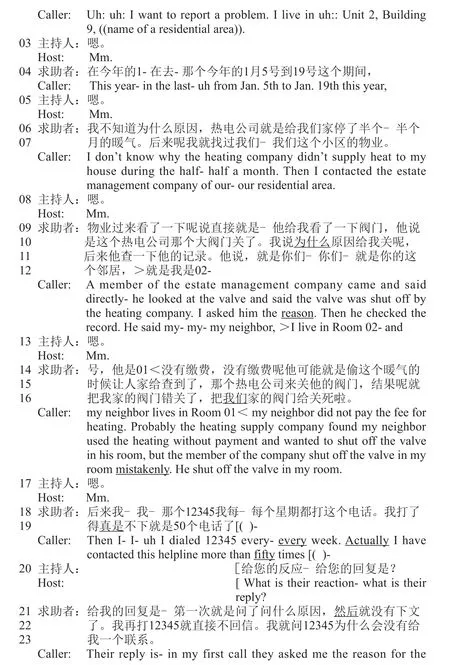

There are also many cases in which citizens’ private problems are reported. Most citizens attribute the reported problems to the unsatisfactory work of the relevant service agencies or the third party and then present their failure to get satisfactory solutions in a routine way. This is illustrated in Extract 3. In this extract, government officials of a district in Jinan are invited to attend the program and deliver responses to citizens’ problems. The caller’s problem is that the heating company stopped heating her house ahead of the stipulated time without any notice or explanation.

In Extract 3, the caller first describes her problem as a transgression by the heating company by pointing out that the heating was cut off ahead of the stipulated time without any notice or explanation. She then presents chronologically the process of finding out the nature of the problem and attributes its occurrence to the failure of the heating company. At line 16, she stresses the words “错” (“mistakenly”) and “我们家” (“my room”) to describe herself as a victim. The turn construction unit (TCU) “把我们家的阀门给关死啦” (“He shut off the valve in my room”) is a repetition of its prior TCU, which could be a way of emphasizing the mistake of the heating company.

At lines 18-19, the caller describes how she tried to solve this problem by herself.She emphasizes recurrently that she has made considerable effort to solve this problem but failed. She stresses the words “每” (“every”), “真是” (“actually”) and“50” (“fifty”) to emphasize her repeated attempts to find out a solution. At line 20,the host interrupts the caller and asks a question about the reply of the helpline 12345,which indicates that she regards the upshot of the caller’s attempts as necessary information on the reported problem.

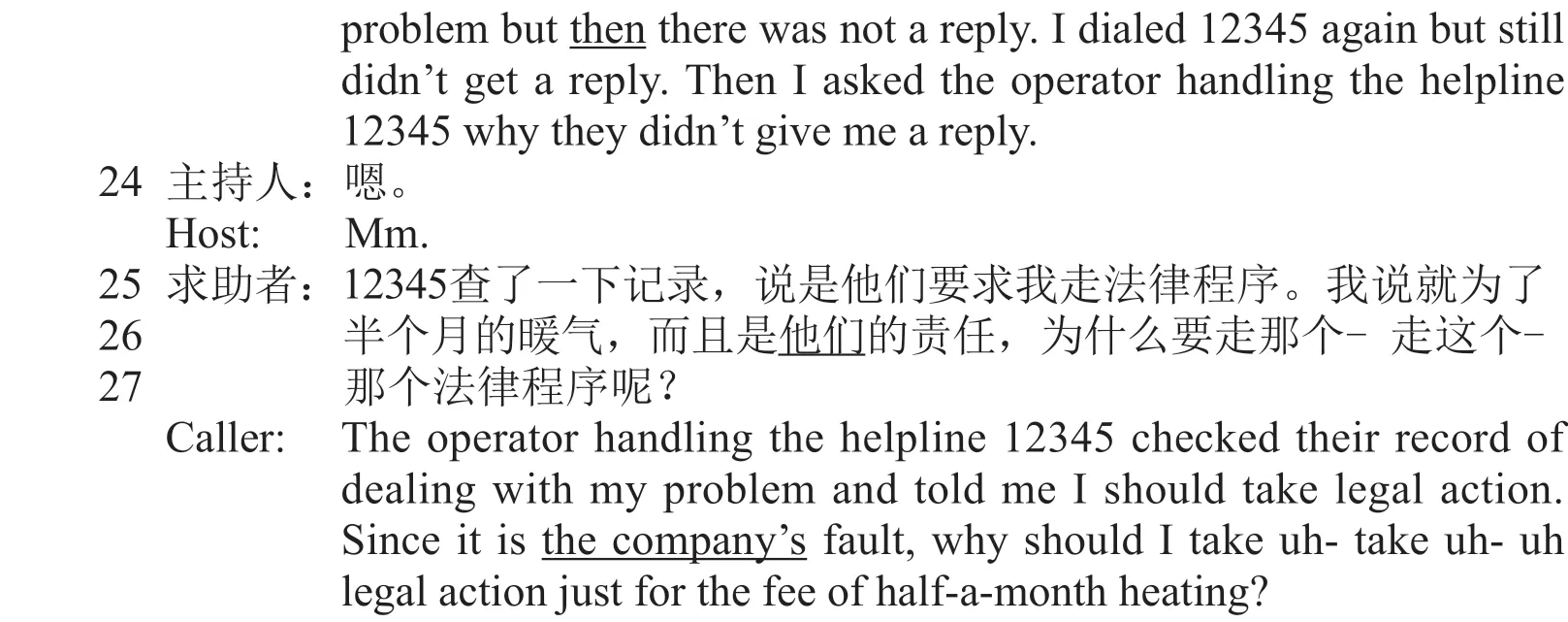

A noticeable point in the caller’s answer to the host’s question is her self-repair(line 21). The beginning of the turn “给我的回复是- ” (“their reply is-”) seems to be a straightforward answer to the host’s question, but the caller cuts off and then describes in detail (at lines 21-23) the absence of a reply and how she pursued a reply again and again. This self-repair and the caller’s detailed description indicate that she cares much about the absence of a reply from the helpline 12345. At lines 25-27, the caller comments on the helpline’s reply as being unacceptable. She stresses “他们的” (“the company’s”) to indicate that the heating company, rather than her, should be responsible for solving the reported problem. Using the word “就” (“just”), the caller means taking legal action will bring her more trouble than benefit. The caller’s attribution of her problem to the failure of the service agency and the lack of a satisfactory solution to it make her believe her request for assistance to be legitimate.

To sum up the analysis of the above three extracts, the two essential components in citizens’ requests for assistance are their reports of public or private problems as transgressions and their complaints about recurrent failure to get satisfactory solutions to their problems from the relevant service agencies. Citizens employ practices, such as extreme case formulations, repetitions and self-repairs, to enhance the legitimacy of their requests and express their stances on reported problems implicitly. In addition to callers’ descriptions, the host asks questions to collect more information, which is in many cases about whether or how relevant service agencies have dealt with reported problems. It is indicated that the host also regards the performance of service agencies as an essential part of problem presentations, which conforms to the helpline’s role of supervising the daily operation of public service agencies. Consequences of the special turn design of citizens’ requests for assistance in this institutional setting will be examined in the next section.

4. Officials’ Granting Responses and Closure of Telephone Calls

In most settings, such as ordinary talk, emergency calls and commercial services,grantings to requests are normally accepted (Kevoe-Feldman, 2015; Schegloff,2007; Zimmerman, 1992), but in some Chinese public service calls, even if officials legitimize callers’ requests and provide solutions to reported problems, these responses are followed by callers’ or the host’s resistance.

4.1 Callers’ resistance

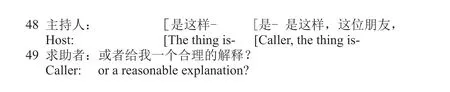

In some telephone calls, after officials provide solutions to callers’ problems, callers pursue an account of why they did not get a satisfactory solution or even a reply from the relevant agencies or the helpline 12345 before the radio phone-in program. Callers’ failed self-help is normally described in their requests for assistance, but some officials may not account for it in their responses. Some callers regard their failed self-help as accountable and therefore pursue an account for it. This is illustrated in Extract 4, which is from the same telephone call as Extract 3. After the caller’s request in Extract 3, the host asks the caller several questions to know more details about the reported problem and then asks the commissioner of the district (which is a district of Jinan), Mr. Zhao, to deliver a response to the caller’s problem. Extract 4 begins with Mr. Zhao’s response.

In Extract 4, at lines 41-43, the official legitimizes the caller’s requests, makes an apology and finds a solution to the caller’s problem. However, at line 44, the caller delivers only a minimal acknowledgement token “嗯” (“mm”), which is not an acceptance of the official’s response. Then she asks for an account for her previous failure to solve it in a routine way (lines 44, 45, 47 and 49), which actually has been described in her request in Extract 3. Again, she uses and stresses extreme case formulations (Pomerantz, 1986), such as “多次” (“many times”), “每个” (“every”)and “没有一个” (“none”), to express her strong dissatisfaction caused by a lack of reply. In Extract 3, the caller’s report of her problem and her complaint about her failed self-help are the two essential components of her request for assistance, but there is not an account for her failed self-help in the official’s response, so at lines 44-49 in Extract 4 she pursues an account. The caller’s resistance to the official’s response suggests that in Extract 3 the caller complains about her recurrent failed self-help not merely to legitimize her request for assistance but also to ask for accountability. Therefore, the absence of an account in the official’s response caused the caller’s resistance. This observation of the caller’s request, the official’s response and the caller’s resistance to the response indicates participants’ orientation to the norm of proportionality (Heritage, Raymond & Drew, 2019).

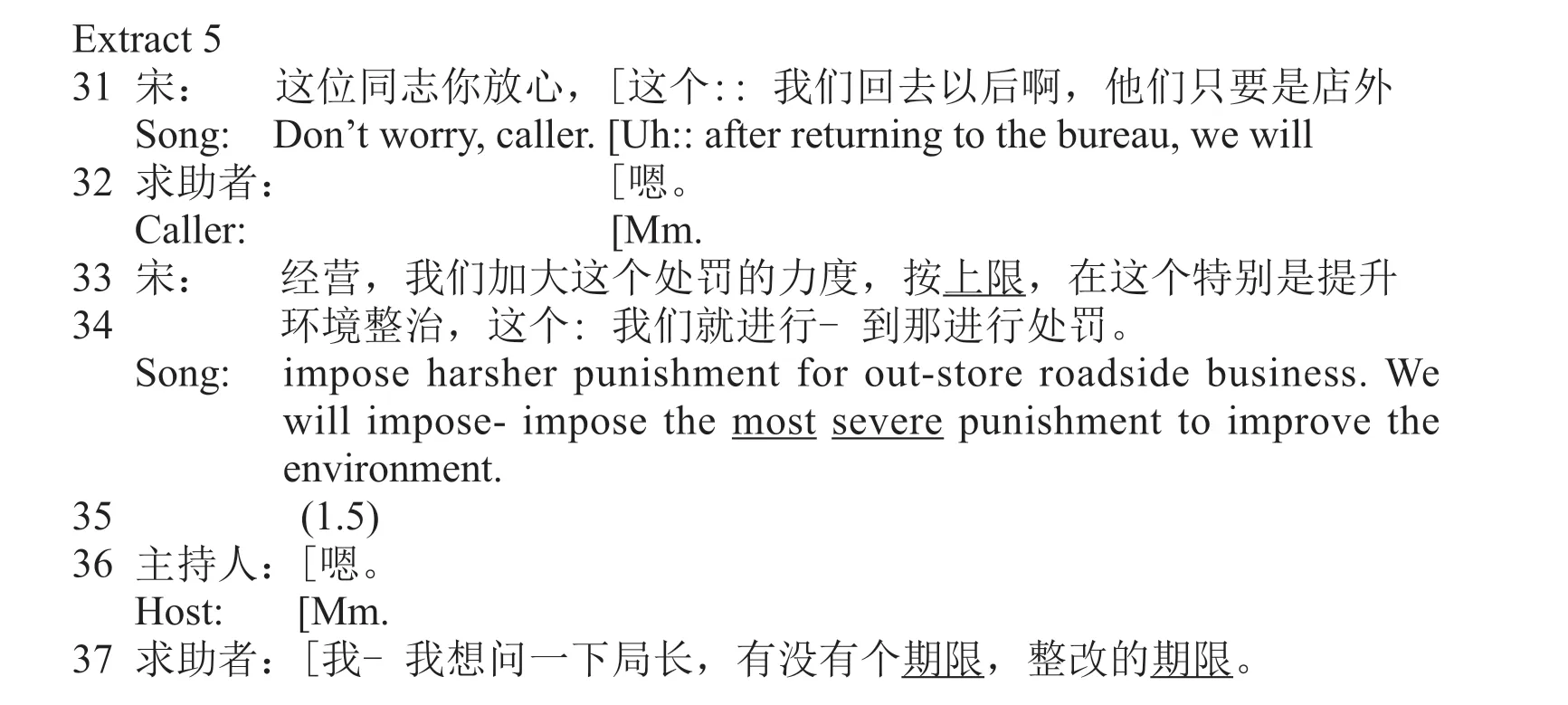

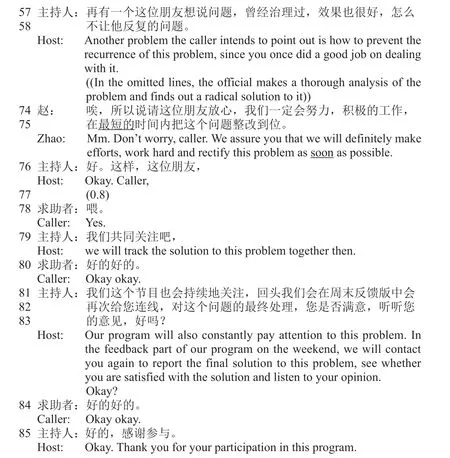

In some telephone calls, after callers’ requests and the host’s following questions,officials provide solutions and promise to solve callers’ problems after the program,but callers challenge the credibility of officials’ future-oriented responses. This is illustrated in Extract 5, which is from the same telephone call as Extract 2. The caller reports the problem of roadside stall business. He has reported it to the official helpline 12345 several times since over a month ago but has not got any reply.The host asks the director of the urban management bureau, Mr. Song, to deliver a response to the caller’s problem.

In Extract 5, at lines 31-34, the official provides a solution to the caller’s problem.By highlighting “加大这个处罚的力度,按上限” (“impose the most severe punishment”), the official emphasizes that powerful measures will be taken to solve the reported problem. However, there is a long silence after the official’s response,which indicates that probably this response is not accepted (Schegloff, 2007). It is followed by the host’s minimal acknowledgement token (line 36) and the caller’s question (line 37).

In the caller’s question at line 37, he repeats and stresses the word “期限”(“deadline”) to show his concern about when the reported problem will be actually solved. Since the solution to the reported problem is future-oriented and under the official’s control, the caller’s question indicates his concern about the implementation of the rectification. Obviously, the type-conforming answer (Raymond, 2003) to this question is the deadline, otherwise, the official should account for why a deadline could not be provided. In the official’s answer at line 38, the earliest starting time of rectification, “今天” (“today”) and “马上” (“very soon”), is promised. However, there is a silence (at line 39) showing the caller’s passive resistance (Clayman & Heritage,2002) to the official’s answer. The caller treats the words “马上” (“very soon”) as a vague expression and asks for a specific time (at line 40). This question shows that the caller regards the official’s answer at line 38 as being insufficient because the deadline of the rectification is not provided. The caller’s question design (at line 40) is abnormal and noticeable. Normally “马上” (“very soon”) means one hour,one day or one week, but the caller asks the official whether “马上” (“very soon”)means a month or half a year. This question design indicates that the caller is actually challenging the credibility of the official’s response probably because of the longterm existence of the problem, the agency’s previous failure to solve it and a lack of account for the failure in the official’s response.

At lines 41-42, the official accounts for the agency’s previous failure to solve the reported problem. His emphasis on “天天” (“every day”) shows that they have been working hard to solve this problem. In his account, he seems to be indicating that they have fulfilled their responsibility but it is a really difficult problem. However, this account occurs after the caller’s question about when actions will be taken (at line 40) and also after the caller’s question about the deadline of the rectification (at line 37). Therefore, it is regarded as an account for being unable to take effective actions within a very short time and being unable to provide a deadline of the rectification.This could be demonstrated by the caller’s criticism of the service agency’s job at lines 45-46 and the host’s pursuit of a solution at lines 47-55. The caller’s criticism seems to be suggesting that members of the service agency are not willing to work hard to solve this problem rather than being unable to do so. In other words, the caller’s concern about the deadline of future-oriented solution escalated into a strong criticism of the agency’s being unwilling to solve the reported problem.

At lines 47-58, the host plays the role of a mediator to eliminate the conflict between the caller and the official and provides guidance for the official’s delivery of an appropriate response. At line 47 and line 57, the host begins her turns with “其实这位朋友想表达的意思” (“actually what the caller means”) and “再有一个这位朋友想说问题” (“another problem the caller intends to point out”), indicating that the conflict may be caused by the official’s insufficient understanding of the caller’s stance. Therefore, the host points out explicitly the caller’s stance on the problem and what the official should do to eliminate the caller’s concerns. At lines 50 and 52, the host first shows affiliation with the official’s difficulty of handling this problem. This sounds like a preface of clarifying the caller’s stance, so the official delivers a continuer at line 53. Then at lines 54-55, the host points out that members of the urban management bureau should solve the reported problem due to their institutional responsibility. Overlapping with the host’s talk, the official delivers a preferred response (Schegloff, 2007) making an agreement with the official’s proposal. At lines 57-58, the host suggests that the official should find out a radical solution to the reported problem, which echoes with the caller’s concern about the recurrent occurrence of the problem. In the omitted part, the official accepts the host’s suggestion, makes a thorough analysis of the problem and presents specific measures to be taken.

At lines 74-75, the official expresses his responsible attitude towards the solution to the caller’s problem. He uses the extreme case formulations (Pomerantz, 1986)“一定” (“definitely”) and “在最短的时间内” (“as soon as possible”) to show his determination and sense of responsibility. The host’s response “好” (“okay”) signals an acceptance of the official’s response. Then, the host turns to the caller as the recipient and tells the caller what will be done next. At lines 79-83, the host promises to supervise the solution to the reported problem and asks for the caller’s opinion on the final solution. In this way, the solution to the reported problem will be under public supervision and partially under the caller’s control. This measure eliminates the caller’s concern about the delayed solution or no solution to his problem after the program. Finally, the caller accepts the official’s response and the host’s proposal.Then the host ends the telephone call.

In sum, due to the caller’s recurrent failure to solve the reported problem in a routine way and a lack of an account for this in the official’s response, the caller wonders whether and when the reported problem will be actually solved after the program. So in the official’s response to the caller’s problem, he is expected to account for their previous failure, find feasible measures to radically solve the reported problem and put the solution to it under public supervision and (partially)under the caller’s control.

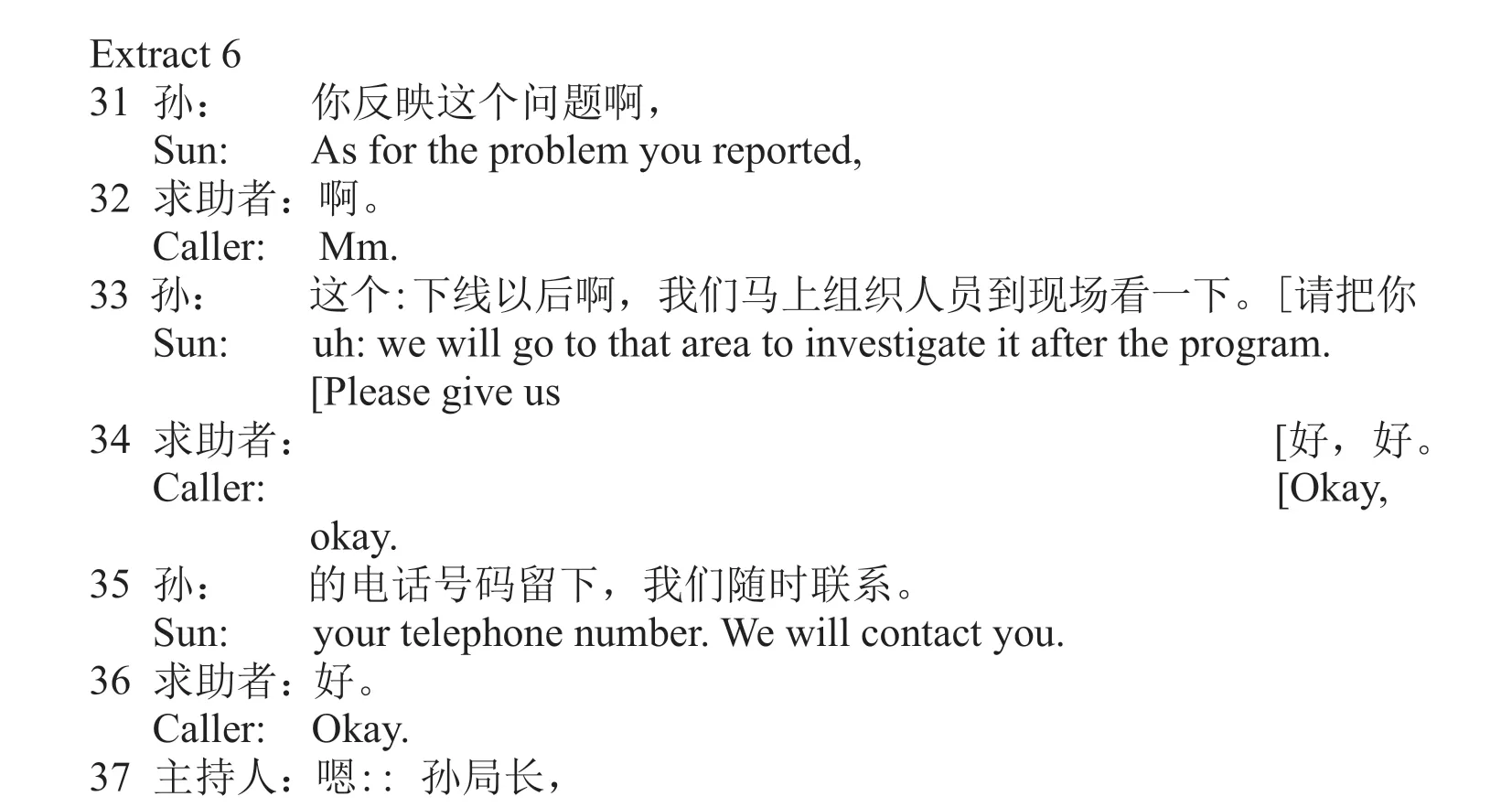

4.2 The host’s resistance

In addition to callers’ resistance, the host’s resistance may also occur after officials’grantings of callers’ requests. In some cases, after officials grant callers’ requests for assistance, their responses are accepted by callers, but the host regards officials’responses as being insufficient from the perspective of the supervisory role of the helpline. This is illustrated by Extract 6, which is from the same telephone call as Extract 1. In Extract 1, the caller reports that a road is full of big holes and complains about his recurrent failed self-help. In Extract 6, an official, Mr. Sun, who is responsible for dealing with the reported problem, delivers a response.

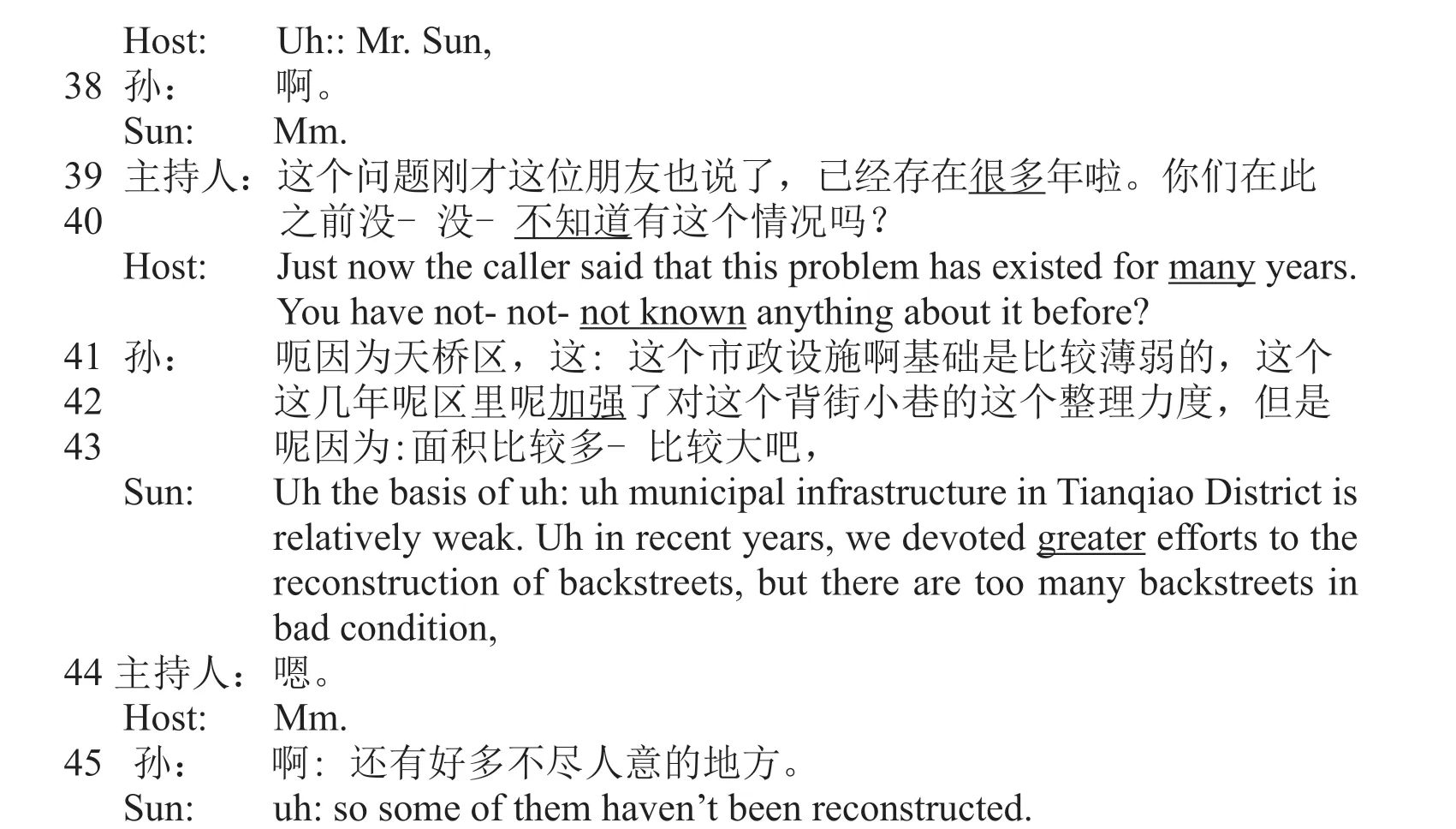

At lines 31-36, the official, Mr. Sun, promises to investigate the reported problem,and this response is accepted by the caller. However, at line 37, the turn-initial position of the host’s talk is occupied by “嗯::” (“uh::”), as a preface of her resistance to the official’s response. The host regards the long-term existence of the reported problem as accountable and therefore pursues an account for it at lines 39-40. Being asked this challenging question, the official faces a dilemma. If he answers “yes”, he has to explain why he did not solve it after knowing it has caused long-term inconvenience for citizens. If he answers “no”, it demonstrates that he did a really bad job because he failed to perceive such a severe and long-lasting problem. The official regards the host’s question as a pursuit of accountability rather than merely a question. At lines 41-45, he accounts for the long-term existence of the reported problem and at the same time claims that they are devoting greater efforts to solve this sort of problem.

In this extract, the host’s resistance to the official’s response and the caller’s acceptance of it demonstrate their orientation to different institutional roles: the caller accepts the official’s response as long as his problem could be solved; the host, as a representative of the helpline, plays a supervisory role, i.e., supervising the work of public service agencies, in addition to solving citizens’ problem. In other words, due to the supervisory role of the helpline, from the host’s perspective both a solution to the caller’s problem and an account for the caller’s failed self-help are regarded relevant in the official’s response.

5. Discussion

This study analyzes citizens’ requests for assistance, officials’ granting responses and citizens’ or the host’s resistance to officials’ grantings in a Chinese radio program public service helpline. Reasons for the occurrence of resistance to granting responses are discovered. Findings of the present study are summarized and compared with previous studies as follows.

The trajectory of request and response in the radio program’s Chinese public service helpline is closely related to its dual institutional task. A unique feature of this helpline is that it is set up not only to solve citizens’ problems but also to supervise the daily operation of public service agencies. The dual institutional task of this helpline has consequences for the turn design of citizens’ requests and the trajectory of request sequences in this setting. Both citizens’ reports of problems and their complaints about previous failure to solve them are essential components in their requests for assistance.After officials provide solutions to reported problems in their responses, many callers wonder why they failed to solve them in a routine way by themselves before and whether the reported problems will actually be solved after the radio phone-in program.

The findings of this study contribute to the study of turn design of requests and preference organization of responses to requests. In this helpline, citizens’ reports of their problems and complaints about their failed self-help in their requests for assistance seek not merely solutions to reported problems but also expect accounts for their previous failed self-help in relevant officials’ responses. This is different from callers’ complaints about their failed self-help in telephone calls to mediation centers, which merely serve to legitimize callers’ requests for assistance and do not make accounts for previous failed self-help relevant (Edwards & Stokoe, 2007). It is indicated that the linguistic resources speakers select in a particular moment and a particular environment only “serve to address the specific contextual conditions that are relevant for accomplishing the action” (Margutti, et al., 2018, p. 58). The futureoriented grantings to requests in Chinese public service calls also have different consequences from those in ordinary talk (Rauniomaa & Keisanen, 2012), in which delayed fulfillment of friends’ requests is not questioned or challenged. In the present study, callers’ resistance to officials’ future-oriented responses is probably caused by the long-term existence of their problems, their recurrent failure to solve them in a routine way and a lack of officials’ accounts for the previous failure in their responses.Callers’ or the host’s solicitations and other further questions following officials’granting responses indicate that beyond the granting/refusal option there are a wide variety of responses that requests make relevant in various settings. This is consistent with the previous finding (Margutti & Galatolo, 2018) that it is not a good choice to treat all variants of a social action as being subject to the same preference principles.

Implications of the present study for officials’ effective communication with citizens are twofold. Firstly, before officials deliver responses to callers’ requests, they should have sufficient understanding of callers’ stances on reported problems, e.g.,whether callers are asking for an apology, compensation, solutions to their problems,or improved quality of public service. As directors of public service agencies, officials are expected not merely to find solutions to reported problems but also to identify problems within the work of relevant service agencies. Secondly, since callers’recurrent failed self-help has probably undermined their trust in the work of relevant service agencies, in officials’ future-oriented responses, they should show strong determination and willingness to radically solve callers’ problems, find out feasible measures and put solutions to callers’ problems under public supervision and (partially)under callers’ control. These two points also have practical implications for responses to requests in other service encounters, such as commercial service encounters.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzes requests and responses in 200 Chinese public service calls. In callers’ requests, in addition to reports of their problems, they make complaints about their previous failure to solve reported problems in a routine way. In this helpline,callers’ requests seek not merely solutions to reported problems but also accounts for citizens’ previous failed self-help. Therefore, in many cases, when officials merely provide solutions to reported problems and promise to solve them soon,their responses are questioned. It is indicated that in addition to the granting/refusal responses to requests, there are a wide variety of other expected responses, which are projected by various turn design of requests made by speakers in various settings. One limitation of the present study is that it only examines one variant of the request social action in a particular setting. The turn design of requests and the trajectory of request sequences in other settings and other languages could be studied in the future.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Visual Literacy in Secondary EFL Education in China: A Semiotic Perspective

- A Systemic Functional Semiotic Investigation of Illustrations in Chinese Poem Books: An Ontogenetic Perspective1

- Gender Ideology in the Definitions of Contemporary Chinese Dictionary

- Discourse Strategies in President Buhari’s Speech on the #EndSARS Protests in Nigeria

- The Challenges of the Virtual Classroom—The Semiotics of Transmedial Literacy in VR Education

- Sermonizing as Pragmatic Act in Sikiru Ayinde Barrister’s Lyrics