Immunoglobulin G in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis predicts clinical outcome: A prospective multi-centre cohort study

2021-12-03MarianneAnastasiaDeRozaMehulLambaGeorgeBoonBeeGohJohnathanHueyMingLumMarkChangChuenCheahJingHiengJeffreyNgu

Marianne Anastasia De Roza, Mehul Lamba, George Boon-Bee Goh, Johnathan Huey-Ming Lum, Mark Chang-Chuen Cheah, Jing Hieng Jeffrey Ngu

Abstract

Key Words: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis; Immunoglobulin G; Autoantibodies; Mortality; Hepatic decompensation

INTRODUCTION

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a growing phenomenon with an estimated global prevalence of 25 %. Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in particular is a progressive form of NAFLD and is associated with poorer clinical outcomes and higher liver related mortality[1]. Independent predictors for poor outcomes include fibrosis[2], obesity and metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus (DM)[3], as well as genetic polymorphisms such as PNPLA3 [4]. NASH is characterized histologically by hepatic steatosis, inflammation, hepatocellular injury and varying degrees of fibrosis[5]. The inflammatory process in NASH is a complex and heterogeneous “multi-hit” pathway in which the innate immune system plays a critical role,driving the progression of liver fibrosis and leading to cirrhosis, liver failure, the need for liver transplantation and death[6 -8]. Less is known, however, about the role of the adaptive immune system and autoantibodies. Autoantibodies are produced by humoral immune responses against self-cellular proteins and nucleic acids and can be physiological or pathological[9]. When used in tandem with clinical findings, they are serological hallmarks for inflammatory autoimmune liver diseases. However, their significance in NAFLD is not well studied despite autoantibodies being present in 25 %-35 % of patients with NAFLD[10 ,11].

Adamset al[10] reported a higher grade of inflammation in NAFLD patients with positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or anti smooth muscle antibodies (ASMA)but the difference was slight (1 .0 vs 1 .2 , P = 0 .02 ) and there was no correlation to clinical significance or outcomes. More recent data from McPhersonet al[12] looking specifically at serum immunoglobulins in NAFLD, showed that elevated serum immunoglobulin A was significantly associated with advanced fibrosis. Similarly,there was no correlation to immunoglobulins being a predictor for mortality or hepatic events independently from fibrosis and other factors. Despite evidence showing association of autoantibodies and immunoglobulins with higher histological grades of inflammation or fibrosis[10 ,12 ,13], other studies dispute these findings[14 ,15], and correlation to clinical outcomes is still not established in NASH.Raviet al[16] reported no significant difference on liver disease outcomes in steatohepatitis patients with positive ANA or ASMA , however, the major limitation of the study was that overall follow-up was short (median 3 years) and alcoholic and non-alcoholic hepatitis were grouped together.

Overall, autoimmune markers such as ANA, ASMA, plasma cells and immunoglobulins with immunoglobulin G (IgG) in particular, are not well studied in NASH and their clinical significance is unknown in this population. Hence, the aim of this study is to determine if autoimmune markers in patients with biopsy proven NASH are independently associated with poorer outcomes. The outcomes measured being all cause mortality and liver decompensation events.

开关变换器的主电路与反馈控制电路构成了一个自动控制系统。常用的开关变换器控制类型有:电压型控制、电流型控制以及电压、电流结合型控制[12-14]。文中所采用的电压控制环路设计如图2所示。

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient selection

Consecutive patients who underwent liver biopsy at Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand (CH) and Singapore General Hospital, Singapore (SGH) were assessed for inclusion in the study. CH cohort consisted of patients with liver biopsy performed from 2008 to 2016 and the SGH cohort from 2005 to 2015 . Patients with chronic liver diseases of other aetiologies such as viral hepatitis, alcohol, toxins or drugs,autoimmune including IgG4 related disease, vascular, metabolic and hereditary causes were excluded. All patients, as per local hospital protocol underwent non-invasive liver testing including serology analysis and imaging to exclude other causes of chronic liver disease. Patients were included in the study if the final histological diagnosis was NASH with NAFLD activity score (NAS) ≥ 3 on biopsy with scores for steatosis, lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning[17].

ANA and ASMA were considered positive if titres were observed to be ≥ 1 :40 . IgG was considered elevated if > 14 g/L. Additionally, if quantitative values were not available, globulin fraction (GF) was calculated by the following equation: total protein/(total protein - albumin). Since IgG is the commonest globulin type[18],individuals with GF > 50 % were defined as elevated IgG. To assess presence of plasma cells, histology reports were reviewed. Plasma cells were scored as positive if any plasma cells were identified on histology specimens by the pathologist. This study conforms to ethical guidelines and was approved by our respective institutional review boards.

Follow-up

Patients from CH and SGH were followed up for clinical events of liver decompensation and all-cause mortality. Liver decompensation event was defined as the development of any of the following: ascites, gastrointestinal haemorrhage secondary to portal hypertension, hepatic encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome.Patients were followed up till 31 st December 2017 . Follow-up was censored at development of first liver decompensation event, death, liver transplantation, or last clinical contact in case of patients lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (interquartile range,IQR) and were compared using unpairedt-test. Categorical variables were compared usingχ2test. The associations of putative risk factors and outcomes were analyzed using Cox proportional hazards regression and are summarized as hazard ratios (HR)with 95 %CI. The time to event outcomes were also summarized using Kaplan-Meier curves. A two-tailedPvalue of < 0 .05 was taken to indicate a statistical significance.All analyses were undertaken using statistical software SPSS version 20 .

RESULTS

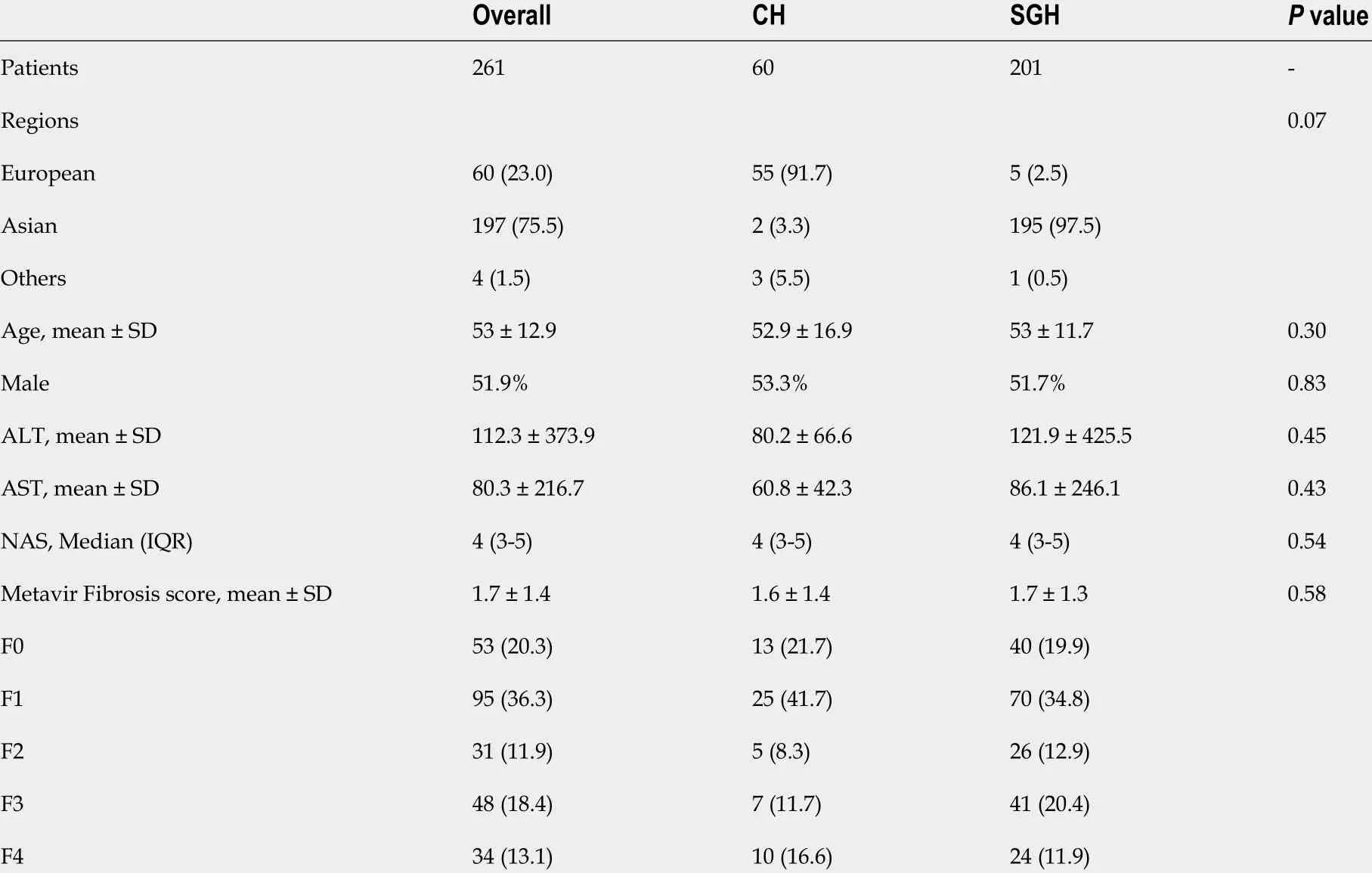

A total of 261 patients met the study criteria. Of these, 201 patients were recruited from SGH and 60 patients from CH. Baseline characteristics of patients are listed in Table 1 .Majority of patients from CH were of European origin (91 .7 %) while 97 .5 % patients from SGH were of Asian origin, reflecting the local population demographic. Median follow-up per patient was 5 .1 years (IQR 3 .5 -7 .5 ). Median age at inclusion in the study was 53 years (± 12 .9 ) and 51 .9 % were male. The median NAS score at diagnosis was 4 (IQR 3 -5 ) and the mean Metavir fibrosis score was 1 .7 (± 1 .4 ). 77 % of patients had data available for body mass index (BMI), and comorbidities including presence of DM, of which the mean BMI was 30 .61 and DM was present in 45 .02 % of patients. There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between patients from SGH and CH (Table 1 ).

Prevalence of autoimmune markers

ANA was the most common positive autoimmune marker present in 27 .8 % patients followed by elevated IgG observed in 23 .4 %. Plasma cells were found on histological examination in 13 % of patients with NASH. ASMA was the least common autoimmune marker and was positive in only 4 .9 % of NASH patients.

Clinical end-points: Liver decompensation and all-cause mortality

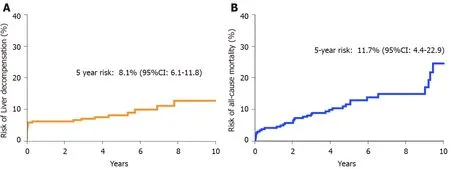

During a cumulative follow-up of 1464 person years, 25 patients developed liver decompensation. There was no significant difference between risk of liver decompensation or all-cause mortality between patients from CH and SGH. The 5 -year risk of developing liver decompensation after diagnosis of NASH was 8 .1 % (95 %CI:6 .1 -11 .8 ) and the 5 -year mortality risk was 11 .7 % (95 %CI: 4 .4 -22 .9 ) (Figure 1 ). Ten patients developed hepatocellular carcinoma of which 7 were male. Median age at diagnosis of HCC was 65 .7 years. Advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis was present in 6 of 10 patients at diagnosis of HCC. During the follow-up period, 36 patients died. Data on cause of death were available for 30 (83 .3 %) patients. Liver related causes of death were observed in 12 cases (40 %), followed by malignancy (30 %), septicaemia (17 %)and cardiovascular causes of death (13 %). Overall, 5 -year risk of all-cause mortality was 11 .7 % (95 %CI: 4 .4 -22 .9 ) (Figure 1 ).

Predictors of Liver decompensation and all-cause mortality

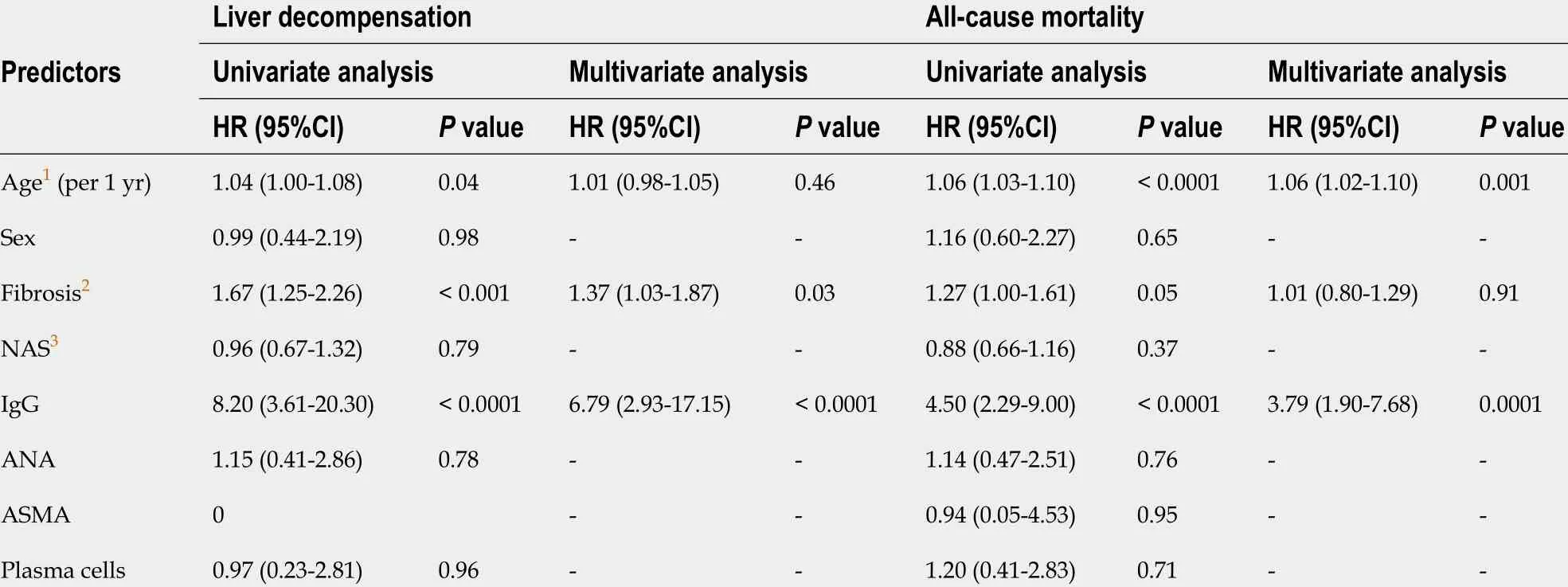

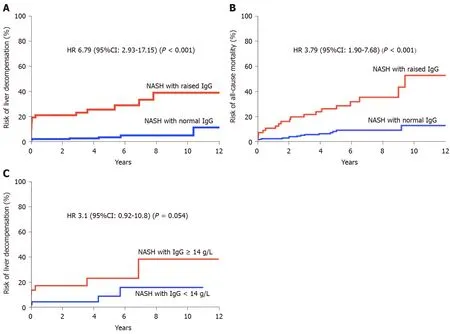

Liver decompensation:In univariate analysis (Table 2 ), factors associated with increased risk of liver decompensation were increasing age (HR 1 .04 , 95 %CI: 1 .00 -1 .08 ),stage of fibrosis (HR 1 .67 , 95 %CI: 1 .25 -2 .26 ) and elevated IgG (HR 8 .20 , 95 %CI: 3 .61 -20 .30 ). Other autoimmune markers (ANA, ASMA or Plasma cells) were not found to be associated with risk of liver decompensation (Table 2 ; Figure 1 ). Multivariate model was constructed with variables found to be significant in univariate analysis. In multivariate analysis, elevated IgG (HR 6 .79 , 95 %CI: 2 .93 -17 .15 ) and stage of fibrosis(HR 1 .37 , 95 %CI: 1 .03 -1 .87 ) were found to be independently associated with increased risk of liver decompensation during follow-up (Table 2 ).

In a sub-group analysis where only patients with quantitative IgG values (> 14 g/L)were included (n= 43 ), a trend of association was observed between elevated IgG and increased risk of liver-decompensation during follow-up. (HR 3 .1 , 95 %CI: 0 .92 -10 .8 ,P= 0 .054 ) (Figure 2 ).

Mortality:In univariate analysis, predictors of all-cause mortality included: increasing age (HR 1 .06 , 95 %CI: 1 .03 -1 .10 ), stage of fibrosis (HR 1 .27 , 95 %CI: 1 .00 -1 .61 ) and elevated IgG (HR 4 .5 , 95 %CI: 2 .29 -9 .00 ) (Table 2 ). In multivariate analysis, age (HR 1 .06 , 95 %CI: 1 .02 -1 .10 ) and elevated IgG (HR 3 .79 , 95 %CI: 1 .90 -7 .68 ) were found to be independent factors associated with increased risk of mortality (Table 2 ; Figure 2 ).Median survival in patients with elevated IgG at baseline was 9 .4 years.

DISCUSSION

In this multicentre cohort study, we examined the association between the presence of autoimmune markers such as ANA, ASMA, elevated IgG and plasma cells on histology with clinical outcomes in patients with NASH. The most pertinent finding of our study is that elevated IgG at diagnosis of NASH was associated with increased risk of liver decompensation and reduced overall survival.

Autoimmune markers are commonly encountered in patients with NASH, however their clinical significance is not well defined. In a study of 225 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD, 20 % and 3 % respectively were found to have the presence of ANA and ASMA[10]. Similarly, in another cohort study of NASH patients, thepresence of ANA and ASMA was observed in 34 % and 6 % of all patients respectively[15]. The findings of our study are consistent with the reported prevalence estimates.While inflammation involving plasma cells is typically observed in AIH, the prevalence of plasma cell infiltration in NASH is not known. In the present study,plasma cell infiltration was observed in 13 % of patients with histological diagnosis of NASH.

Table 1 Baseline characteristics, n (%)

Table 2 Univariate and multivariate analysis of predictors of clinical outcomes

Figure 1 Overall risk of liver decompensation and all cause mortality. A: Overall risk of liver decompensation; B: Overall risk of all cause mortality.

Figure 2 Raised immunoglobulin G and risk of liver decompensation and mortality on multivariate analysis. A: Raised immunoglobulin G (IgG)and risk of liver decompensation; B: Raised IgG and risk of all-cause mortality; C: Raised absolute IgG > 14 and risk of liver decompensation. IgG: Immunoglobulin G.

Association of ANA and/or ASMA with histological severity of NASH has been examined previously in multiple cohort studies and yielded conflicting results[10 ,12 -15 ,19]. None of the studies, to our knowledge, have assessed association of autoimmune markers with long-term clinical outcomes. We found that the risk of liver decompensation or all-cause mortality were not associated with the presence of either ANA, ASMA or plasma cells, thereby suggesting that these are non-specific markers of inflammation and unlikely to be pathogenically relevant.

On the contrary, elevated IgG at diagnosis of NASH was independently associated with increased risk of liver decompensation (HR 6 .79 , 95 %CI: 2 .93 -17 .15 , P < 0 .0001 )and all-cause mortality (HR 3 .79 , 95 %CI: 1 .9 -7 .68 , P = 0 .0001 ) during follow-up.Majority of the excess mortality in the elevated IgG cohort were liver-related. It needs to be highlighted that diagnosis of probable or definite AIH was conclusively ruled out in all patients based on the international standardised criteria and no patients were treated with immunosuppression except in cases of organ transplantation.

We do not have a concrete biological explanation for the observed pathogenic role of IgG in NASH, however several mechanisms are plausible. Firstly, oxidative stress in NASH may induce production of IgG by deployment of adaptive humoral response[5 ,20]. Animal and human based studies have shown that IgG directed against products of lipid peroxidation such as Malondialdehyde and 4 -hydroxynonenal appears to be elevated in NASH and correlates with disease severity[20]. Secondly, anti-endotoxins IgG levels were observed to be higher in patients with NASH compared to controls (48 vs 10 GMU/mL), and IgG levels corelated with severity of NASH[20 ,21]. Endotoxins are generally derived from the gut microbiota[21] and are potential triggers for inflammation and insulin resistance, driving oxidative stress in NASH. Therefore, elevated IgG may be representative of high endotoxemic burden leading to rapid progression of NASH. Lastly, it is possible that elevated IgG in patients with NASH may represent an overlap with a mild degree of autoimmune hepatitis. However, currently no diagnostic criteria exist to define NASH-AIH overlap syndrome.

Our study has several limitations which ought to be acknowledged. Quantitative immunoglobulin values were not available for all patients and globulin fraction was used as a surrogate marker of elevated IgG. While globulin fraction has previously been utilised as an effective surrogate marker of hyper/hypogammaglobulinemia[22]it is possible that we may have under or overestimated the IgG effect on clinical outcomes. However, upon restricting analysis to those patients with quantitative IgG values, a similar effect was observed (although statistically non-significant),suggesting that the observed association between IgG and poor clinical outcomes is true rather than a type-1 error. Data for pre-existing medical comorbidities and current medications were only available for 77 % of patients, which may have confounded overall results. However, all patients were on follow up with a specialist and would have received standard of care for hepatic decompensation, regardless of compliance to treatment. Lastly, the diagnosis of NASH was based on unblinded histology interpretation by the local pathology team, consequently an element of inter-observer bias cannot be ruled out. Our study design involved two different population cohorts from two large tertiary centres. Despite having different ethnic compositions, there were no significant differences in baseline-characteristics at inclusion in the study between the two centres suggesting that our results are generalizable. Importantly,both centres have national electronic records available making complete data ascertainment of clinical events possible.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we report that ANA, ASMA and plasma cells are commonly present in patients with NASH but carry no prognostic significance. On the contrary, elevated IgG is an independent predictor of increased risk of liver decompensation and reduced overall survival in patients with NASH. Presence of elevated IgG therefore represents a more aggressive NASH phenotype. Identification and close monitoring of these patients is prudent to improve overall clinical outcomes.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research methods

This is a prospective, multi-center study. Patients with biopsy proven NASH were included and multivariate analysis was performed to determine if any of the autoimmune markers (IgG, ANA, ASMA) were independent risk factors for mortality and hepatic decompensation

Research results

Elevated IgG was an independent risk factor for both mortality and liver decompensation after multivariate analysis with adjustment for age and fibrosis stage.The exact pathophysiology is unknown but IgG levels could possibly correlate to disease severity due to anti-endotoxins IgG and oxidative stress.

Research conclusions

Elevated IgG is an independent predictor of increased risk of liver decompensation and reduced survival in patients with NASH. It could represent a more aggressive NASH phenotype.

Research perspectives

Further research is needed to validate and reproduce this finding and to also establish the pathophysiology and underlying biochemical mechanisms for this observation.

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Survivin-positive circulating tumor cells as a marker for metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Minimum sample size estimates for trials in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review of a support resource

- Genome-wide map of N6 -methyladenosine circular RNAs identified in mice model of severe acute pancreatitis

- Liver injury changes the biological characters of serum small extracellular vesicles and reprograms hepatic macrophages in mice

- Hepatitis B: Who should be treated?-managing patients with chronic hepatitis B during the immunetolerant and immunoactive phases

- Recent advances in artificial intelligence for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma