The COVID-19 pandemic and the future of public health

2021-11-16JinlingTang

Jinling Tang

Shenzhen Institute of Advanced Technology,Chinese Academy of Sciences,China

Abstract The COVID-19 pandemic provides us with a rare opportunity to deeply examine the validity of the construction of modern medicine,which is armed by science,and focus more on technologies than on people’s values and more on new ideas than on conventional wisdom.The world’s responses to the COVID-19 emergency have revealed a badly weakened public health system -one of the three pillars of medicine,the other two being basic medicine and clinical medicine.A 100 years ago,public health was the only effective measure for combating infectious diseases,which were then the main cause of human death.It is still a decisive weapon against COVID-19 and other communicable diseases alike,but was barely recognized and trusted at the beginning of the pandemic by the general public and even some international strategists.However,the epidemic has been effectively contained in China by non-pharmacological public health measures,which saved valuable time for the development of vaccines in the country and probably hundreds of thousands of lives as well.Public health aims to improve the health of the entire population by using societal methods.It is not simply a medical issue,and building a strong public health system requires broad participation from various sections of society.

Keywords China,COVID-19,epidemic,epidemiology,pandemic,public health

The sudden outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 has had great impacts on various aspects of life across the world,including the economy,society,education and scientific research.In particular,this once-in-a-century pandemic has brought public health,a discipline which was hardly known to the general public,under the spotlight.

Historically,public health has been a silver bullet for combating infectious diseases,which were the main cause of human death in the past,and has made significant contributions to the victory of humankind against those deadly diseases.Today,public health has turned from a giant to a dwarf,becoming the shortest of the three pillars of modern medicine -basic medical science,clinical medicine and public health.We cannot help but wonder,what are the weak links in public health? What can we do if a similar pandemic strikes again?

It is clear that a social transformation centred on public health is on the horizon.Only by gaining a comprehensive understanding of the big picture can we ‘give the prescription that works for controlling the pandemic’.If we keep our eyes only on the pandemic,we will miss a once-in-a-century opportunity to build a strong public health system,which is an inseparable part of united,holistic medicine.

1.Public health:A star of the past

From the birth of medicine to the mid-20th century,infectious diseases were a major cause of human death.For thousands of years,the fight against infectious diseases has been the main theme of medicine.

Historically,pandemics of infectious diseases could be more important than political,economic and military endeavours (McNeill,2010).The Black Death in the mid-14th century killed over a third of the Europe’s population and weakened the foundations of authority.The 1918 influenza pandemic caused some 50 million deaths,hastening the end of the First World War.These are just two examples of the impact of infectious diseases on history.

In 1915,Edward Trudeau passed away,ending his lifelong battle with tuberculosis.The following line from his epitaph is known to every doctor today:‘To cure sometimes,to relieve often,and to comfort always’.It shows the human face of medicine,but also reveals its frustration.Humankind has been battling infectious diseases for thousands of years,yet with little progress in finding effective cures.Therefore,people placed hopes in prevention.

The first route to prevention was in the form of macro-investigations or population studies (Porter,2006).The breakthrough occurred in the middle of 19th century,when puerperal fever spread in Europe.Women who had previously shown no signs of illness died of fever soon after giving birth,and the mortality rate ran as high as 10% in some places.The disease became a major cause of death in women.

At that time,the connection between bacteria and disease was not yet known,and viruses had not been discovered.Most people in the medical field believed that miasma (damp,unpleasant,smelly air) was the cause of puerperal fever.In 1846,Ignaz Semmelweis,a young doctor at the Austrian General Hospital,studied the puerperal fever cases in the delivery room and postulated that invisible ‘cadaverous particles’ brought by doctors from the autopsy room to the delivery room and then passed on to the mother were most likely the cause of the fever.As a result,he recommended that doctors wash their hands before delivering babies -a measure that quickly reduced mortality from puerperal fever by as much as 80%.Semmelweis’s discovery was humanity’s first successful attempt to truly understand and effectively prevent infectious diseases,which were contagious but could be contained by washing hands(Best and Neuhauser,2004).

In 1854,the city of London was plagued again by cholera.John Snow,an anaesthesiologist,noticed a particularly high death toll around a well in London’s Broad Street and suspected that the disease might have been transmitted by water.He then took away the handle of the well so people could not fetch water from it,and the cholera around Broad Street soon subsided.By that time,although the relationship between micro-organisms and diseases was yet to be established,there were already measures to effectively prevent and control infectious diseases:simply by washing hands and cleaning drinking water.Hygiene soon emerged as a new discipline and an early form of public health (Charles River Editors,2020).

Hygiene in the early 20th century was not only a cutting-edge technology in the medical field,but also an important part of medical theories and practices (Starr,2017).According to Google Books Ngram Viewer,in the records of Western books,from the beginning of the 20th century to the end of the Second World War,the terms ‘hygiene’,‘sanitation’ and ‘public health’ appeared almost as often as terms of clinical medicine,which demonstrated the importance that society accorded to public health at that time.

In 1979,in his famous bookThe Role of Medicine,British medical sociologist McKeown (1979) found that mortality from tuberculosis in the UK had stayed on a steadily downward trajectory for the past 150 years.During that period,three Nobel Prizelevel breakthroughs relevant to tuberculosis were made in medicine (the discovery of tuberculosis bacillus as the cause of tuberculosis,the discovery of streptomycin for treatment of tuberculosis and the invention of bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine for prevention of tuberculosis),but the mortality from tuberculosis in the UK seemed to be little affected by these big scientific achievements.What,then,were the driving forces behind the trend? McKeown argued that they were improvements in nutrition,social work and hygiene.

The British Medical Journaldid a survey in 2007 to find out the most important scientific breakthroughs in medicine since the founding of the journal in 1840 (Ferriman,2007).There were many familiar terms on the list,such as antibiotics,vaccines,anaesthesia and DNA,but what came out on top were sanitation and hygiene.

There is a legendary figure in the world of surgery -Christian Barnard,who performed the first successful heart transplant in humans.At a world surgical congress in 1996,he said that the three real contributors to human health were the plumber,the ironworker and the bricklayer,who ‘did more for the human race than all the surgeons put together.It wasn’t the doctor who wiped out the typhoid,it was the plumber...’ (Barnard,1996).What he did not point out is that behind the plumbers,ironworkers and bricklayers are the public health workers who laid down the theories and evidence for successful sanitary and public health measures and actions.

More than 100 years ago,the best a country or a community could do to improve public health was to prevent infectious diseases by improving people’s hygiene and sanitation.Starting from that time,hygiene and public health have merged,forming the nucleus of public health today.Hygiene as a form of public health measure has made an undeniable contribution to mankind’s conquest of infectious diseases.What,then,is its status in modern medicine?

2.Public health from a ‘giant’ to a‘dwarf’

At the heart of the rise of modern medicine is the flourishing of clinical diagnosis and treatment technologies,which is attributable largely to the second route established by humanity to understand and combat infectious diseases:‘microscopic’ investigations and the treatment of individuals.

The microscopic understanding of medicine was first made possible by the invention of the microscope in the early 17th century,which revealed the existence of tiny things that are invisible to the naked eye.In 1861,Louis Pasteur discovered that fermentation was caused by exogenous microscopic organisms.In 1876,Robert Koch,a German clinician,proved for the first time the causal relationship between bacteria and disease by demonstrating that bacillus anthracis causes anthrax.

These new theories opened up opportunities for the development of medical instruments and devices that can look into the body and new methods of diagnosis and treatment of individuals.The thermometer is perhaps the first widely used medical investigation instrument.We use it to measure our body temperature.If our temperature is high,we may go to see a doctor.Nowadays,medical instruments have become so big and complex that we can’t use them in homes or small clinics.That partly makes the hospital a centre of medical practice today.However,the rise of hospitals and the treatment of individuals have also mirrored the decline of public health.

The system of modern medicine can be viewed as a ‘tripod’ standing on three legs:basic medicine,which studies biomedical mechanisms and paves the ways for new diagnostic and therapeutic methods;clinical medicine,which provides care for individual patients;and public health,which focuses on prevention and population strategies.Today,however,the ‘leg’ of public health has become too short,leaving the tripod of medicine on shaky ground.The weakened public health system has been fully exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Modern medicine is a Western-oriented medical system armed with science and technology,with basic medicine as the main force of theoretical research and clinical medicine as the primary actor in practice.What is the role of public health? If the COVID-19 pandemic had not struck,the general public would have barely noticed the existence of the field of public health,let alone its roles,theories and methods.In less than 100 years,public health has gone from boom to bust,turning from a ‘giant’into a ‘dwarf’.

Technology brings mankind into the proudest age of material civilization.The advance of science and technology has been so successful that the scientific way of thinking has penetrated into every corner of our lives.As a result,we tend to trust new and unconventional thinking more than what is often taken to be common sense,and we tend to think that new ideas are better and more useful than conventional wisdom.Hygiene was the most advanced science in medicine over a century ago and is not at all outdated in containing the pandemic today,but many people still did not believe that at first.

‘Fragmentation’ is another important feature of science and technology.Most of our professionals are thus specialists,not generalists,and it is difficult for us to see the full picture and make decisions based on the whole.In addition,knowledge and technology,as huge productive forces,can also be huge moneymaking tools.Truth may be distorted by people’s pursuit of benefits,which makes it difficult to separate true and biased information,particularly in the era of social media,further adding to the difficulty of decision-making in urgent,complex situations.This is the macro-context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

3.The role of public health in fighting COVID-19

Technology-driven modern culture has pre-shaped our thinking on the responses to COVID-19.The remarks of Bruce Aylward,Assistant Director-General of the World Health Organization,at the beginning of the pandemic,authoritatively expressed this view:‘In the world of preparedness and planning,I suffer the same biases as or maybe error of thinking as many people...we don’t have a vaccine,we don’t have a therapeutic’.(World Health Organization,2020) How can we defeat this pandemic?

The strategy for controlling the pandemic is then self-proven:we are dealing with an infectious disease;we need to isolate the pathogen as quickly as possible,develop diagnostic reagents and speed up research on vaccines and drugs.We hope that this would eventually help us bring the pandemic under control.Our basic research did not fail to live up to our expectations.Before we could be certain that the virus was transmissible among humans,we had already identified it and developed nucleic acid diagnostic reagents.However,what truly helped China successfully control the epidemic was not cuttingedge technologies but old-fashioned hygienic measures such as quarantine,social distancing,hand-washing,mask wearing and universal temperature monitoring.(Liang et al.,2020).These nonpharmacological interventions have given China valuable time to develop vaccines and build a longlasting mechanism to eventually contain the epidemic.In early responses,new technologies are important,yet they are only additives,not the medicine itself.To the day of this forum,effective vaccines and drugs for COVID-19 management are still in the experimental stage.

A similar response strategy would be anticipated if another epidemic of a new emerging infectious disease strikes in the future.Effective control of an infectious disease of unknown cause is not something that can be achieved by simply waiting for the development of vaccines and drugs.Although scientific progress is always desirable,conventional wisdom is not necessarily outdated.When we face a new problem,it is not new technologies but the most appropriate methods that will work.This is an important lesson we have learned from this pandemic.

Moreover,there is something more important than science and facts;that is the values that we consider important and desirable in life.Facing the same disease,the same technology and the same evidence,different countries have adopted vastly different strategies.This shows that technology is not the only factor that determines people’s choices.There is something more important than technology:the weight of the public’s health and the value of life in the hearts of the decision-makers.

Problems in agriculture cannot be solved by medicine.Likewise,given the gravity of the public health crisis caused by COVID-19,the victory over the virus is bound to be a victory of public health -the societal approach to humans’ health problems.To protect people’s lives and health,China has mobilized the entire society,introduced quarantine-centred hygienic measures and succeeded in controlling the epidemic.All of this is the best illustration of the mission,theory and methods of public health and the most powerful exemplification of public health practice.

4.Building a holistic medicine with a strong public health component

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic,the central role of public health in fighting the disease was not quickly recognized.This shows that public health as a whole,not just any part of it,is weak.The weakness of public health is in essence the weakness of modern medicine.

In the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak in early 2020,virologists,clinicians and epidemiologists quickly joined in the investigations of the epidemic in Wuhan,the epicentre of the disease.They represented basic medicine,clinical medicine and public health -the three pillars of modern medicine.They gathered information,collected evidence,looked for possible causes and then reported their findings to the decision-makers.They could all see just one side of the problem;they could all be right.Then who should the decision-makers listen to? Can the decision-makers tell whether the specialists are right or wrong? Who should the decision-makers rely on when making the final decision? These are difficult questions to answer and also areas where we have not reflected deeply in learning lessons from our responses to the epidemic.Furthermore,when reflecting on those lessons,it is easy to focus only on the disease prevention and control system,or even only on the handling of health or infectious disease emergencies.If we do that,we will be seriously underestimating the importance of public health and miss a once-in-a-century opportunity to build a stronger public health system.

What,exactly,is public health? Modern public health has two layers of meanings.The first is the health of all people (the public),especially the less privileged.This is the original intent of public health.The second is hygiene,which is a set of theories and methods developed in our past responses to infectious diseases.Public health also has two distinctive features.One is population,which means that medical issues shall also be viewed from a population perspective and resolved with a societal approach.For example,public services such as water supply,waste disposal,air pollution control,the health system,health policy and the health insurance system are not intended to serve just a few,but to benefit all.The other is altruism,so public health services are mostly provided collectively and led by the government and society through multidisciplinary cooperation.

Public health today can be viewed as ‘the science and art of studying from a population or societal perspective and addressing the problems related to health,disease and health services by using population or societal means,with the ultimate goal of improving the health of the entire population’ (Tang,2015).Put simply,public health is what we as a society do collectively to assure the conditions in which people can be healthy,according to the US National Academy of Medicine (Institute of Medicine,2003).

The population perspective is a systematic,holistic and comprehensive perspective that requires the observer to see the forest as well as the trees.Imagine,when the epidemic struck,if we had focused and spent all our resources on treating individual patients and conducting laboratory research,without knowing where the source of infection was or where the most vulnerable regions or communities were;if we had not introduced societal measures such as lockdowns and national mobilization;if we had not established a unified chain of command and close inter-agency collaboration;if we had not conducted field investigations on the source of infection,route and intensity of transmission,incubation period,incidence and fatality rate;and if we had failed to acquire information about the development stage and trend of the epidemic,it would have been impossible for us to bring the epidemic under control in a short time.

As in any other field,there are many populationlevel issues in medicine and health care,in addition to the control of infectious diseases.For example,what are the major diseases and risk factors we face as a community? How many primary care clinics,hospitals and health-care workers are needed in a city? What should be the appropriate number of physicians in each hospital department? How should hospitals and primary care clinics be geographically distributed? How can inequities in health care be addressed? What counts as disease? What are essential medicines? Who should be given treatment?What kinds of treatment are cost-effective?

Without a holistic view,without a population perspective and without a community strategy,we will not be able to deal with these issues effectively.Therefore,we can say that our health ministers,health commissioners,hospital directors,health insurance managers,medical guideline makers and influential physicians should all command essential knowledge of public health,because what they are concerned with and manage are the medical and health issues of an entire region or population,which,by their very nature,are public health issues.

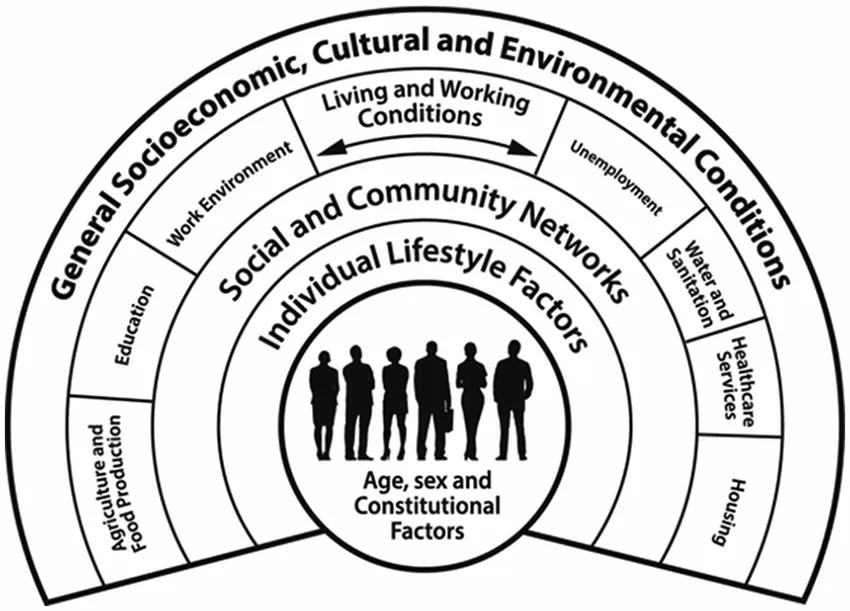

We are now only discussing public health in the health field,which is still a quite limited deliberation.Figure 1 shows the widely known proposal of social determinants of health (UK Department of Health,2021).We can see that almost every thing is related to health.When talking about health,focusing only on the health sector is far from enough for a healthy society.

Figure 1.The social determinants of health.

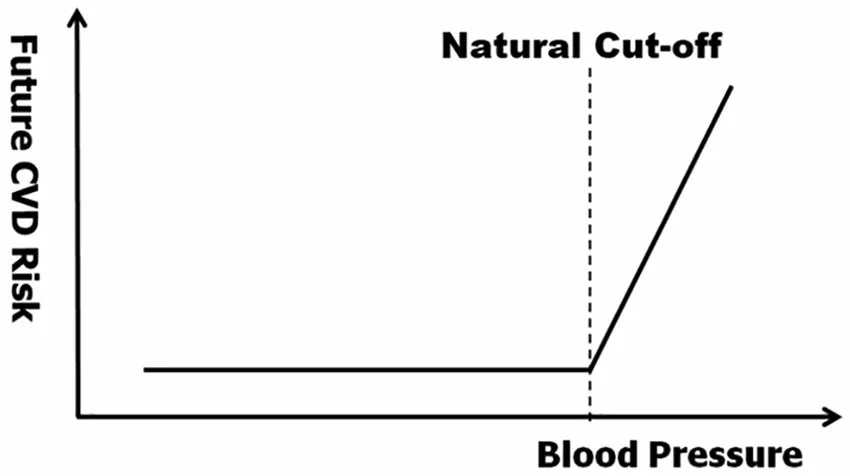

Figure 2.Blood pressure,risk of future cardiovascular disease and the diagnostic cut-off point for hypertension.

5.The paradoxes of public health and the limits to its success

If public health is so important,why is it barely visible in society? The reason is that it is barely on our radar anymore,partly because there are many eyecatching new technologies,and partly because,like air,it is important to life but can barely be seen.In fact,water supply,sewage disposal,environmental protection,food and drug regulation,sanitation and quarantine,vaccinations,health care,health laws,the Red Cross,the Patriotic Health Movement and so on are all social mechanisms and systems built to protect human health and life.When something is too important,special institutions with specially allocated resources will be established either from scratch or by gradually separating them from the health sector.

Public health is by no means limited to the health sector.It is not just a matter of medicine and health and cannot be left entirely to health workers.It involves economics,culture,ethics,law,science,technology and many other fields and requires the participation of and advocacy from the whole society.On the other hand,there are paradoxes that are constraining the development of public health and limiting its impacts.

First,the better public health does,the less credit it gets.If all diseases are prevented,no credit can be awarded.Sun Tzu,the Chinese military strategist who wrote theArt of War2000 years ago,observed that truly great generals are often those without glorious achievements on the battlefield.Such great generals are,however,not greatly rewarded today.

Second,the better public health does,the higher the future cost of health care will be.The longer people live,the more diseases they may suffer and the more health-care resources they may consume in the future.

Third,the better public health does,the more likely it is to run into conflict with clinical medicine in places where hospitals need to make a profit.If diseases are prevented,hospitals cannot make money,so public health will not be popular.

Fourth,the scope of public health practice is big,but the theoretical establishment is small.Social establishments that are set up to protect health and life are many,and all are related to public health,but those working on developing and guarding public health theories are few.In China,most of them are in public health schools and centres for disease prevention and control,with limited manpower and resources.

6.The need for the population perspective in clinical medicine

The population perspective of public health seems to have little to do with clinical medicine,which works at the individual level.However,without a population view,we can see only part of the picture while losing sight of other important things.This is the case for all human undertakings,and clinical medicine is no exception.

To a large extent,the lack of a population view in medicine explains why the number of patients keeps growing.

Take hypertension as an example (Figure 2).Before the hypothetical natural cut-off point,despite increases in blood pressure,the future risk of cardiovascular disease remains the same,and people in such a situation should not be called ‘hypertensive’patients.However,after reaching the cut-off,the risk of cardiovascular disease increases proportionally to the increase in blood pressure.People in this situation can be called hypertensive patients because,for them,higher blood pressure means a higher risk of cardiovascular disease,and lowering their blood pressure through medical interventions may lower their cardiovascular risk.This is how elevated blood pressure is,in theory,made into a disease.

However,through decades of epidemiological studies involving hundreds of thousands of people,it has been found firmly that the risk of cardiovascular disease increases almost linearly as blood pressure increases,and an objective inflection point in the relationship between hypertension and the risk of cardiovascular disease simply does not exist.Without such an inflection point,what blood pressure value should be used as the cut-off point to define hypertension?

Historically,the diagnostic cut-off point for hypertension has been adjusted downward four or five times.Every time,it creates many new hypertensive patients.It is asserted that the prevalence of hypertension has increased by a few times in the past decades,but the public does not know that this is to a large degree a result of reductions in the diagnostic cut-off point for the disease.One study shows that,following the reduction in the diagnostic cut-off points for hypertension,hyperlipidaemia and hyperglycaemia around 2000,the number of these patients in China doubled,adding 359 million new patients to the group (Hu et al.,2017).If all of them were to be treated by drugs at average costs in 2010,the total costs could run as high as 270 billion yuan,or 56%of total government spending on health care in that year.According to the newest recommendations in the American hypertension guidelines,China would add some 300 million more hypertensive patients.

In fact,it is the same situation for cancer.Cancer does not appear in the form of one big lump at onset.It starts with a genetic mutation in a cell,which may develop into several cancer cells and then carcinoma in situ (Welch et al.,2011).It may continue to grow and eventually metastasize and cause death.In a population,many people may have early-stage cancers,but not all small cancers will develop into big lumps,so only a very few people will have large cancerous tumours.And,as for hypertension,the risk of dying from a cancer is proportional to the size or stage of the tumour,and most cancer patients will die of other causes rather than the cancer itself.

How big in size should a tumour to be considered a cancer? (Doust et al.,2017).Unlike for hypertension,the diagnostic cut-off point for cancer is largely determined by advances in cancer-detection instruments.The instruments today are becoming better and more sensitive and can detect smaller and smaller tumours.That is partly why we now have more cancer patients than in the past.

In summary,there is extensive evidence to prove that disease is not an objective,discrete and blackand-white entity,but a subjective judgement made by humans on top of its biomedical basis.The lower the diagnostic cut-off point is set,the more patients there will be,and vice versa.If we do not take a population view,we will not be able to see this point and act sensibly;if factors beyond biomedicine are not included in the consideration,we cannot even convincingly define what a disease is (Doust et al.,2017;Yang et al.,2017).A small change in the diagnostic cut-off point can have a huge impact on the health-care system and expenses of a country or a region,so we cannot just see the trees while losing sight of the forest.

7.The future of public health

Public health is by no means just about the outbreak of infectious diseases or health emergencies;it represents the population or holistic view of medicine.

Where does it come from? It originated from the initial intent of society to protect and improve the health of the public,and there is thus a great deal of altruism in it.Hygiene as the means to achieve this goal is the crystallization of human ingenuity in preventing infectious diseases and has made undeniable contributions to improving the public’s health.

Where should it go? There are too many population-or society-level problems in the construction of modern medicine that limit the quality,efficiency and equity of health services in all countries.These problems are not simply medical issues and cannot be left to health workers alone;their resolutions must be based on social,political,legal,economic,moral and many other considerations,and require the support and participation of the whole society.

It must be stressed that the inability to see and resolve major medical and health issues at the community or societal level is the real weak link in the public health system in China and elsewhere.If this gap cannot be filled,healthy development of medicine would not be possible.

In the face of the epidemic,what is missing in our reflections on public health?

When a major crisis strikes,we all hope we can receive warnings as early as possible.But warnings are not always effective,because they might not be heard or understood.Coming back to the example of Ignaz Semmelweis:the obstetrician argued that it was the doctor who passed on ‘cadaverous particles’to the mother,contrary to the mainstream ‘miasma’theory at the time.He was suppressed and pushed aside by the mainstream medical circle and soon lost his job and ended up in a mental hospital.John Snow’s theory of waterborne cholera transmission was not immediately recognized by the mainstream either.To make matters worse,neither Semmelweis nor Snow was famous in society.Probably,their views could not be heard or people could not tell whether they were right or wrong,or just could not trust them.

So,when a major epidemic strikes,the ability to provide early warning is crucial for an effective public health emergency response but is not easy to achieve.Although China responded to the COVID-19 outbreak far more quickly than in the case of the SARS outbreak in 2003,more reflections on this matter is still needed.

It should also be noted that facts are not equal to decisions,and that reliable facts do not necessarily lead to good decisions.Scientists provide evidence rather than make decisions,and decision-making is a political act,especially when it involves multiple social sectors.Decision-makers have to consider the trade-offs between the pros and cons of various major options beyond health and medicine.They must also take into account currently available resources and balance the value orientations of different social groups.That is why countries faced with the same virus,the same epidemic and the same facts have taken vastly different actions.

Another question:What are the implications of the epidemic for scientific culture?

First,science puts too much emphasis on novelty.This is right for the advance of science but not necessarily for solving practical problems.The COVID-19 pandemic tells us that the ‘high technology’ from a century ago is still the most powerful instrument for controlling newly emerged infectious diseases today.Is there any use for new technologies? Yes.But,till now,new technologies are playing only a secondary,assisting role.Isolating people -the wisdom of the past -is still the main strategy in our response.

Second,scientific disciplines are too compartmentalized.All our experts are authoritative in their own fields,but might not see the whole picture.We need specialists,but also need to bridge the gaps between different disciplines.To do that,we need generalists who can see things from a higher plane.The experts’ task is mainly to provide facts and truth.In the capital-driven commercialist world,truth and profit are,however,inextricably linked.Because of this,the version of truth we hear may often be incomplete or distorted.I am an epidemiologist and can be seen as a professional observer of the COVID-19 ‘drama’,so it is easier for me than for most of the lay public to tell whether a piece of information is reliable or not.Unfortunately,people are often confused and might not trust the reliable information.

Third,science is not the same as belief;it is a tool.In Chinese philosophy,instruments are not equal to morality,and tools are not equal to values.Even though we know the facts,that does not mean that we can always make good decisions.We seek truth,but truth is not equal to dreams.On major issues,we must get the relationship between science and faith right.

Friedrich Engels said that there is no great historical evil without a compensating historical progress.History has taught us that the transformation of a nation’s health-care system is not based on the calculations of science and efficiency but on the construction of great ideas.

The idea behind the 1848 public health revolution in the UK was to protect the health of the poor,and the flag bearer of the campaign was Sir Edwin Chadwick,a local lawyer.The idea behind the establishment of the National Health Service of the UK in 1948 was to provide free health care for all,and one of the key campaigners was Lord William Beveridge,an economist and the then president of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

At the end of my chapter titled ‘The origin and development of public health’ inThe Theory and Practice of Public Health in China,I wrote the following words with high hopes for the future:

At the turning points in the history of public health stand the lawyers,sociologists,economists,philosophers,educators,physicians,and many more.They have given public health a broad vision and tremendous vitality,and transformed its development trajectory with their faith,commitment and hard work.(Tang,2015)

Today,so many more people are starting to pay attention to public health,which is truly encouraging.The future of China’s public health is in the hands of each and every one of us.

Acknowledgement

This article is based on a report delivered at the Second China Scientific Culture Forum:COVID-19 Response and the Construction of Scientific Culture on 3 June 2020.I thank Ms Wang Yiwen,an editor of Liaowang Institute,for drafting and editing the article according to my speech.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research,authorship,and/or publication of this article.