SARS-CoV-2 with concurrent coccidioidomycosis complicated by refractory pneumothorax in a Hispanic male: A case report and literature review

2021-11-02JoscilinMathewSundarCherukuriFatmaDihowm

Joscilin Mathew, Sundar V Cherukuri, Fatma Dihowm

Joscilin Mathew, Sundar V Cherukuri, Fatma Dihowm, Department of Internal Medicine, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, El Paso, TX 79905, United States

Abstract BACKGROUND The incidence of secondary coinfections particularly fungal infections among severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is not well described. Little is known of the complications that could be encountered in such conditions.CASE SUMMARY A 50-year-old Hispanic male who was a prior smoker presented with shortness of breath. He was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2. He improved and was discharged with home oxygen. A month later, he presented with sudden onset cough and shortness of breath. Chest X-ray showed development of right-sided tension pneumothorax, right pleural effusion and an air-filled cystic structure. Computed tomography thorax showed findings suggestive of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis. Coccidioides antigen was positive, and fluconazole was initiated. For pneumothorax, a pigtail catheter was placed. The pigtail chest tube was later switched to water seal, unfortunately, the pneumothorax re-expanded. Another attempt to transition chest tube to water seal was unsuccessful. Pigtail chest tube was then swapped to 32-Fr chest tube and chemical pleurodesis was performed.This was later transitioned successfully to water seal and finally removed. He was discharged on a four-week oral course of fluconazole 400 mg and was to follow up closely as an outpatient for continued monitoring.CONCLUSION Pneumothorax is associated with a worse prognosis, especially with comorbidities such as diabetes, immunosuppression and malignancy. Suspicion for concomitant fungal infection in such patients should be high and would necessitate further investigation.

Key Words: SARS-CoV-2; COVID-19; Coccidioidomycosis; Co-infection; Fungal infection; Tension pneumothorax; Refractory pneumothorax; Case report; Literature review

INTRODUCTION

Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) first emerged in Wuhan, China and is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)[1].Radiological findings include multi-lobar bilateral ground glass opacities and consolidative opacities[2]. An uncommon complication of the infectious process is the development of pneumothorax[1,3,4]. Although often correlated with risk factors, such as smoking, subpleural bleb formation, and as a sequalae of other pulmonary diseases,such as cystic fibrosis, malignancies, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, there are few reported cases worldwide that link pneumothorax formation with SARS-CoV-2, making it one of lesser encountered adverse effects. Though little is known about the association between pneumothorax and SARS-CoV-2, its presence tends to quantify a worsening prognosis.

As the disease continues to be more rampant worldwide several cases of coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 with other infections were reported. These cases included coinfection with other viral infections, such as influenza and molluscum contagiosum virus, less commonly bacterial infections, and rarely fungal infections[1-4].

Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal infection caused by Coccidioides immitis and is predominantly seen in Southwestern America, Mexico, and parts of South America[5].Coccidioidomycosis has been found to affect various organ systems, though pulmonary manifestations appear to be the most common. It is spread through inhalation of airborne fungal spores (arthroconidium) and dust exposure increases the risk of acquiring infection. Clinical presentations can range from asymptomatic, to influenza-like pneumonia, to severe respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis[6]. Radiographic findings range from diffuse pneumonia-like consolidations, nodular parenchymal lesions, and hilar thickening to cavitation and effusions[6,7].

Symptomatology can be very non-specific and can mirror the symptoms of SARSCoV-2 closely, making it difficult to differentiate without appropriate testing. Though little is known about clinical presentations involving both coccidioidomycosis and SARS-CoV-2, it is very likely that co- infection worsens prognosis, increases the risk of complications, and impacts treatment options pursued. In this case report, we discuss the coinfection of SARS-CoV-2 with concomitant coccidioidomycosis infection, that was further complicated by refractory pneumothorax.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 50-year-old Hispanic male presented to our facility after experiencing sudden onset cough and shortness of breath of one day duration.

History of present illness

One day prior to admission, he started noticing sudden onset cough and shortness of breath. He was admitted to our facility one month prior and was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 at the time. Of note, he had an approximately 7.5 pack year history of cigarette smoking and had quit approximately four months prior to hospitalization. A chest x-ray obtained at admission showed multifocal airspace opacities in mainly bilateral middle and lower lobes, as well as a 6.1 cm pneumatocele or bulla in the medial right lower lung adjacent to the cardiac border. He was started on azithromycin, as well as a regimen including vitamin C, vitamin D, and zinc (institutional practice at that time). Additionally, he was requiring supplemental oxygen at 3 Lvianasal cannula. He was discharged under stable conditions with home oxygen. He had discontinued supplemental oxygen usage at home approximately 2 wk prior to current hospitalization. Apart from new onset of non-productive cough and worsening shortness of breath, he denied any other accompany symptoms.

History of past illness

Past medical history consisted of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Personal and family history

Social history was significant for approximately 7.5 years smoking history, occasional alcohol use and no illicit drug use. He worked as an electrician. Family history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus in his father and sister.

Physical examination

In the Emergency department, he was tachycardic with a heart rate of 120 and hypoxic, with an O2saturation of 88% on room air, and diminished breath sounds,hyperresonance with percussion, and asymmetric chest wall excursion on right side were noted on examination. On our examination, post placement of a pigtail chest tube, he was noted to have non-labored respirations, normal respiratory rate, and an O2saturation of 94% on room air; physical exam findings included significantly diminished breath sounds to auscultation in the right lower lung fields, midline trachea, and yellow pleural fluid output from the pigtail catheter. SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid testing on admission remained positive and he was saturating at 94% oxygen on room air.

Laboratory examinations

The following laboratory values were noted: Serum protein of 9, pleural protein of 7.2,serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) of 242, and pleural LDH of 2401, and met Light’s criteria for an exudative effusion. Serologic studies were obtained to investigate the etiology of his cavitary lesions and were positive for coccidioides antigen.

Imaging examinations

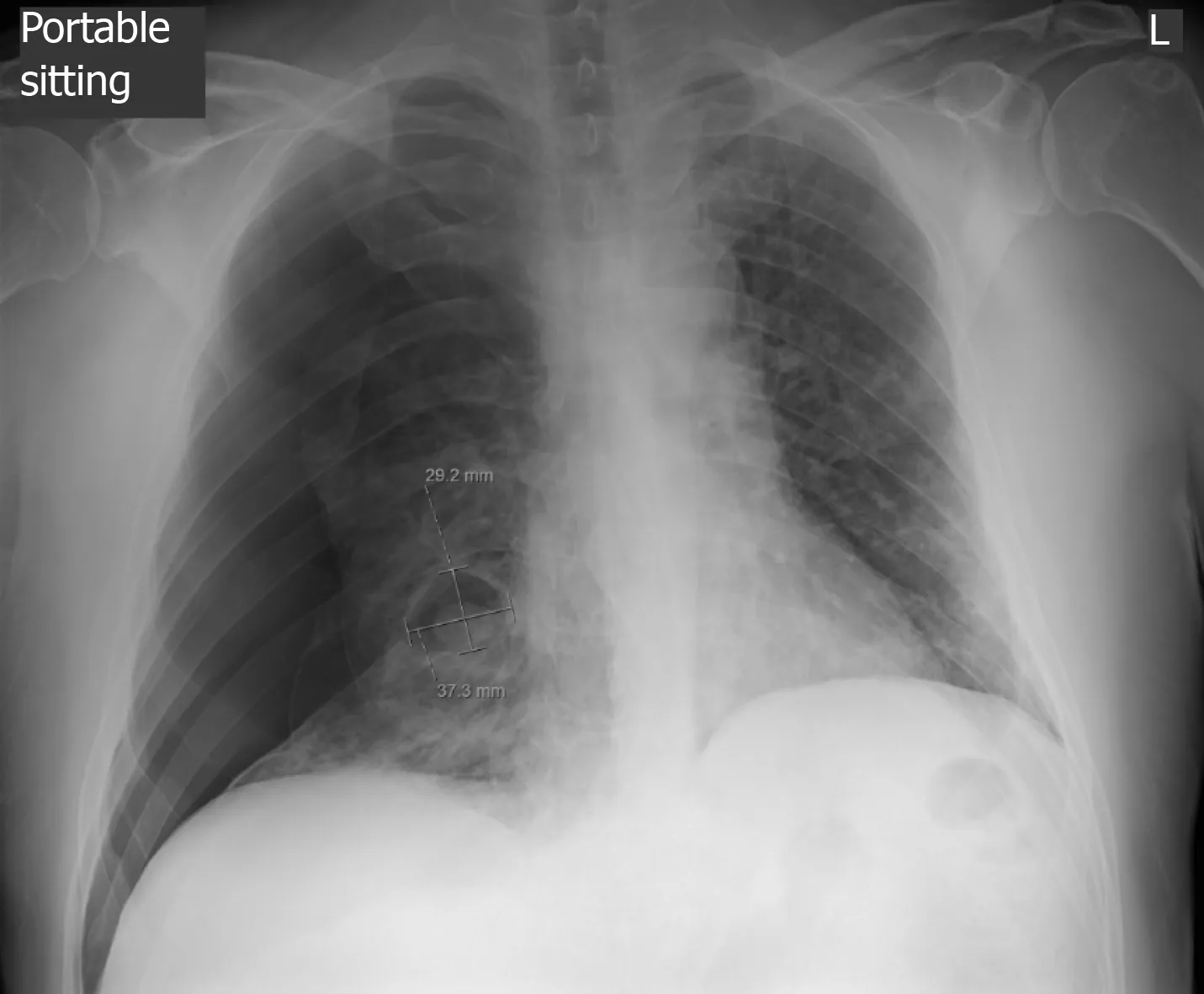

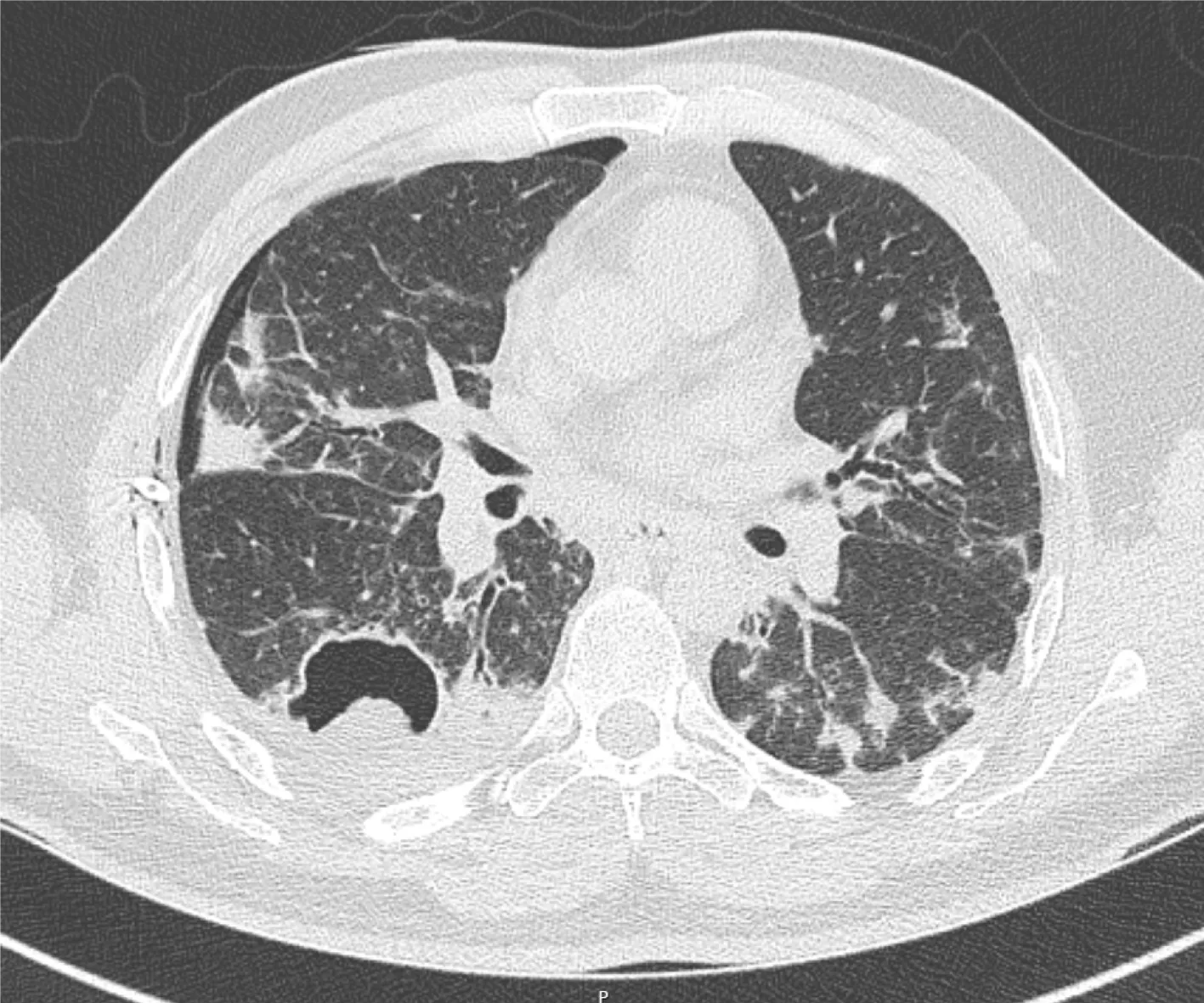

An initial chest X-ray, obtained at time of emergency department evaluation, showed early development of a right-sided tension pneumothorax, with an associated collapse of the right lung and depression of the right diaphragm, and a right pleural effusion.Additionally, it also showed a 3.7 cm × 2.9 cm air filled cystic structure with a round solid dependent component in the right lung lower zone, adjacent to the right cardiac border (Figure 1). A 14 Fr Wayne pigtail catheter thoracostomy was performed by an Emergency Medicine physician and drainage was noted. After stabilization of the patient, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest was also obtained to better visualize the cavitary lesion. It showed the thin walled cavitary lesion with a fungal ball in the superior segment of the right lower lobe, as well as multiple cavitary nodules in bilateral upper lobes and in the superior segment of the lower lobes,suggestive of pulmonary coccidioidomycosis (Figure 2).

Further diagnostic work-up

Figure 1 Chest radiograph of the patient. The image shows development of large right-sided pneumothorax with associated collapse of the right lung, as well as a 3.7 cm × 2.9 cm air-filled cystic structure with a round solid dependent component in the right lower lung.

Figure 2 Computed tomography thorax image. The thorax image depicting thin wall cavitary lesion with a fungal ball in the superior segment of the right lower lobe, right pneumothorax, and diffuse ground glass opacities and densities in bilateral lungs.

The patient was started on an antibiotic regimen that initially consisted of amphotericin B liposomal due to suspicion for central nervous system involvement.The chest tube was placed to suction at 20 mm to address his pneumothorax. The patient’s antibiotic regimen was later switched to fluconazole 600 mg PO daily after the patient developed an acute kidney injury after initiating amphotericin.

Once there was observed interval improvement of the pneumothorax on follow up chest X-rays, the pigtail chest tube was switched to water seal, but unfortunately, the pneumothorax re-expanded. Another attempt was made with the chest tube set to suction and transitioned to water seal; however, re-expansion occurred again. The pigtail chest tube was then swapped to a 32-Fr sized chest tube and chemical pleurodesis was performed by the cardiothoracic surgical team. With the new chest tube set to suction, follow up chest X-rays showed improvement. After 48 h of suction,it was transitioned to water seal and no re-expansion of the pneumothorax was noted.The chest tube was then removed and follow up chest X-rays confirmed no residual pneumothorax.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the presented case is SARS-CoV-2 with concurrent coccidioidomycosis infection complicated by refractory pneumothorax development.

TREATMENT

Throughout the hospital course, the patient continued to saturate well above 92% on room air and required minimal to no supplemental oxygen. He had no further episodes of respiratory distress, though a repeat nucleic acid test continued to show positivity for SARS-CoV-2. He was discharged with a four-week oral course of fluconazole 400 mg and was to follow up closely as an outpatient for continued monitoring.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient has had an uneventful post-hospital clinical course. He has continued his anti-fungal medication outpatient with his primary care physician. The latest chest radiograph has shown resolution of the right lower lung cavitary lesion.

DISCUSSION

Literature review methods

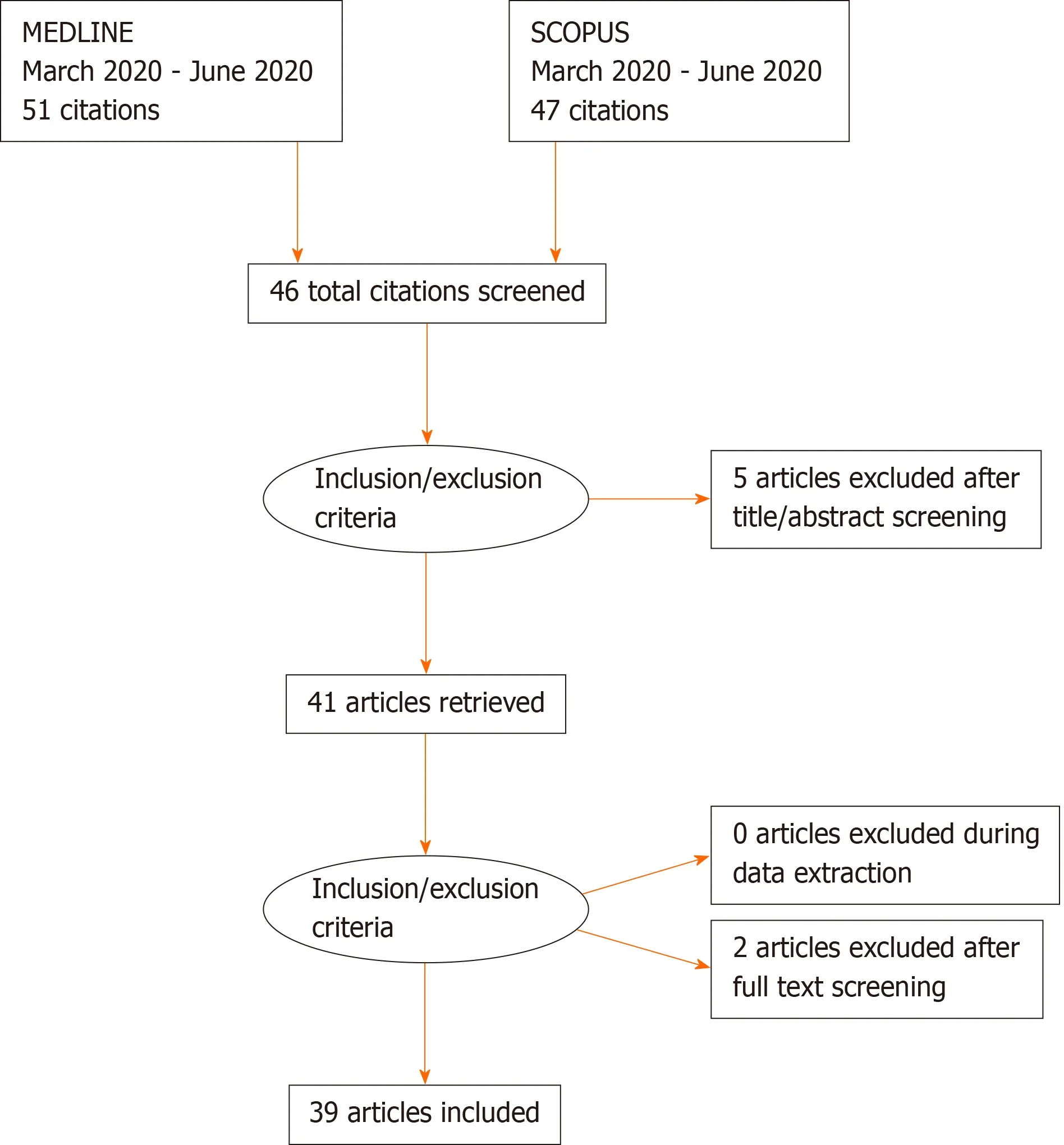

MEDLINE and SCOPUS were the database accessed to seek relevant articles listed from March to October 2020. Articles were searched using the keywords- “COVID-19”,“coronavirus” and “pneumothorax”. Reports that were not indexed on MEDLINE and SCOPUS were excluded from our review. Only articles originally written in English were selected in this review (Figure 3).

Literature review results

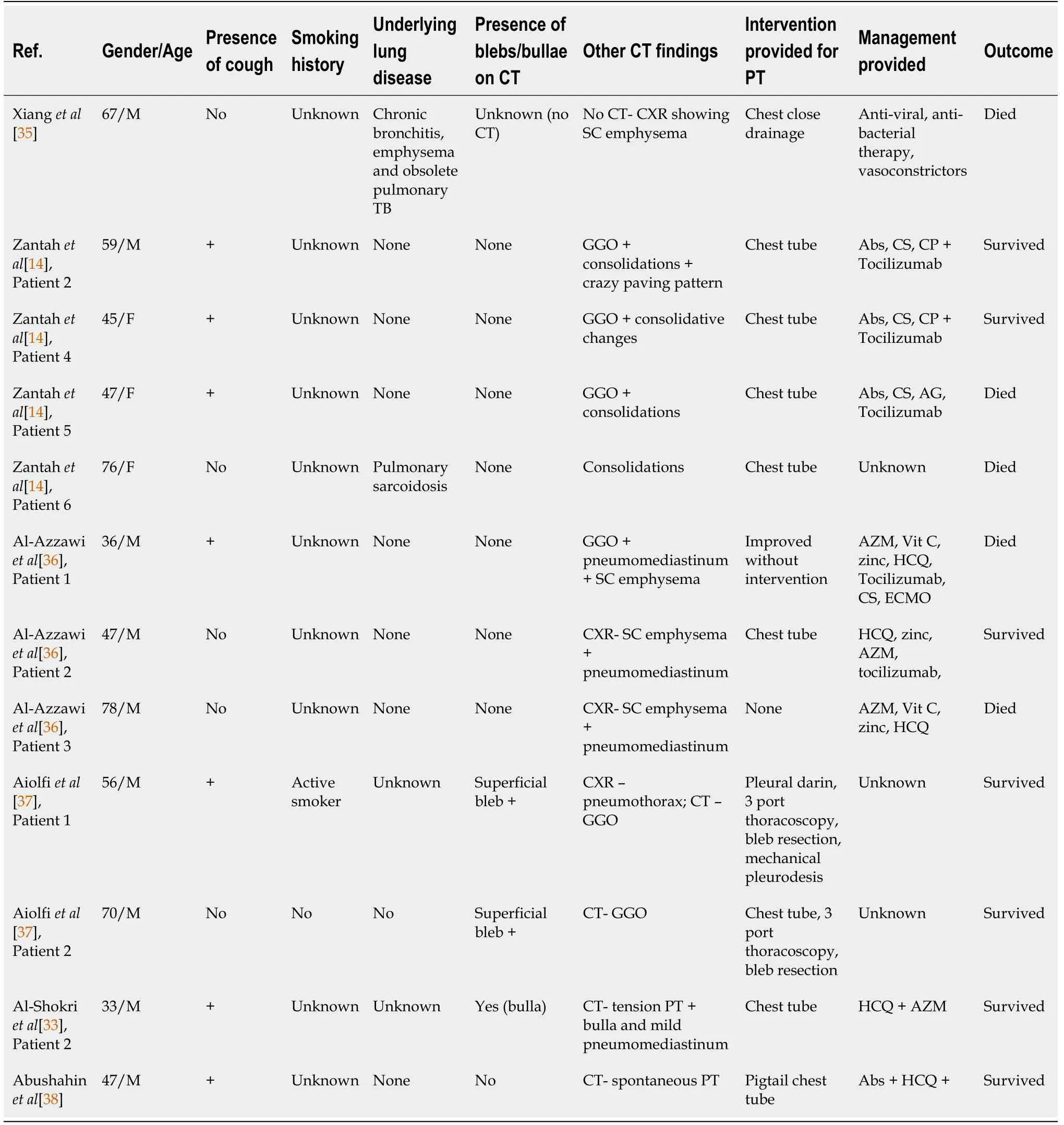

Table 1 and Table 2 summarizes the findings of several case reports of pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Total 39 case reports were included in our literature review. Pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum have been reported in people aged 20-80 with median age being 56. More cases have been reported in men (74%) as compared to women (26%). The presence of cough was reported in 67% of patients. Only 3 out 19 (15.8%) patients with known smoking history were smokers, while 16 out of 19 (84.2%) were non-smokers. Of the patients with recorded past medical history, only 5 in 34 patients had underlying lung pathology (asthma). The presence of blebs was described in 5 patients (12.8%). Tension pneumothorax was noted in two cases only. Invasive mechanical ventilation prior to development of pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum was recorded in 12 (30.7%)patients. While 24 out of 35 (68.5%) patients required intervention for pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum. Review of the outcomes in these patients revealed 21 of 36(58%) patients showed favorable response while 15 in 36 (41.6%) patients did not survive. Among the patients who required invasive mechanical ventilation, only 5 in 12 (45.5%) patients survived.

Table 1 Literature review on reported pneumothorax cases in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among non-ventilated patients

IMV: Invasive mechanical ventilation; PT: Pneumothorax; GGO: Ground glass opacities; HFNC: High flow nasal cannula; AG: Anticoagulation; HCQ:Hydroxychloroquine; AZM: Azithromycin; CP: Convalescent plasma.

Table 2 Literature review on reported pneumothorax cases in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 among ventilated patients

Discussion of the case

Our patient presented with pneumothorax, a rare finding in SARS-CoV-2 infections. A 52-patient retrospective study by Yanget al[4] noted 1 patient (extrapolated to 2% of all cases) who had pneumothorax development. Similarly, another study by Chenet al[1]noted only 1 out of 99 patients in their analysis developed a pneumothorax in the setting of SARS-CoV-2. Given the scarcity of cases, it is difficult to anticipate what factors could have contributed to the development of pneumothoraces.

While our patient was a prior smoker, several case reports show history of smoking or underlying lung pathology does not necessarily increase risk of developing pneumothorax[8-10]. While prolonged smoking history does make the lung more vulnerable, ARDS has been shown to be a greater risk factor for developing pneumothorax. ARDS is associated with decreased lung compliance and higher propensity for barotrauma, increasing the opportunity for developing pneumothorax[11,12]. ARDS continues to be one of the most common indications for invasive mechanical ventilation. Invasive ventilation escalates the danger of alveolar injury and formation of cystic lesions, bullae and pneumothorax[1-3,11-13]. Incidence of pneumothorax secondary to invasive mechanical ventilation is high and is even greater in the setting of ARDS. According to Zantahet al[14], the duration and severity of ARDS along with barotrauma sustained with the use of high tidal volume and minute ventilations, high peak inspiratory pressures (PIP) and high positive end expiratory pressurescorrespond to the increase rates of pneumothorax seen in mechanically ventilated patients. The frequency of pneumothorax was noted to be higher in ARDS patients on longer duration of mechanical ventilation according to Gattinoniet al[15].

Another finding that seems to be consistent across several reported cases, is the incidence of prolonged cough prior to the development of pneumothorax (Table 1).Persistent cough can increase alveolar pressure and induce alveolar rupture causing air leaks resulting in pneumothoraces, pneumomediastinum, and subcutaneous emphysema[8,13,16]. Another risk factor is the presence or development of a pneumatocele or bulla during the early stages of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia[9,12,13]. Our patient was noted to have developed a bulla or pneumatocele during his first admission, and approximately 30 days later, presented with acute symptoms, secondary to a new pneumothorax. Literature review shows most instances of pneumothoraces occurred spontaneously with only two reports of tension pneumothorax noted[9,11].

There have been several reports of coccidioidomycosis cases with pneumothorax development. Rashidet al[10] noted three different cases of exposure, with initial presentations of either an absence of systemic symptoms or presence of low-grade fevers, fatigue, in combination with sudden onset dyspnea and chest pain. These patients were subsequently found to have large pneumothoraces alongside the coccidioidomycosis cavitary lesion. Treatments varied for these cases, ranging from brief antifungal courses of ketoconazole and amphotericin B therapies to requiring additional lung wedge resections. Coccidioidomycosis can lay dormant for many years, though reactivation of disease state is noted with immunosuppression.Interestingly, in our patient it flared up after initial treatment of COVID-19. It remains unclear whether a SARS-CoV-2 associated cytokine storm could have possibly triggered the fungus. While our patient did show several features that elevates the possibility of developing pneumothorax, it is unclear at this time whether the presence of concomitant coccidioidomycosis could have potentially been a confounding factor.Though we would need more studies to confirm this.

In our case, it is unclear whether pneumothorax was caused by SARS-CoV-2,Coccidioides or a combination of both. However, the pattern of pneumothorax formation seems to be similar between the two with bleb formation. Review of literature shows the development of pneumothorax tends to increase as the SARSCoV-2 disease progresses and appears to be associated with a bad prognosis[2]. In patients with prolonged history of dry cough or intubated patients who are noted to have increasing oxygenation requirement, low threshold is advised to conductimaging to rule out pneumothorax. Along with other radiological studies to rule out other common etiologies like pulmonary thromboembolism, flash pulmonary edema,cardiac tamponade or worsening pneumonia[17]. Apart from roentgenograms, lung ultrasound is a convenient study that can be done at bedside[18]. Though CT continues to be the preferred modality. If pneumothorax is noted and its requires the use of a chest tube drain, Akhtaret al[19] noted use of an anti-viral filter attached to pleural drain bottle reduced the risk of aerosolization.

Figure 3 PRISMA 2009 checklist.

Although, our patient did not require active management of SARS-CoV-2, we anticipate dual treatment for SARS-CoV-2 and coccidioidomycosis would require tailoring of medications. When utilizing Remdesivir, a nucleoside analog targeting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for use against SARS-CoV-2, elevations in liver enzymes are common. AST and ALT levels above five times the normal formed an exclusion criteria in the study conducted by Goldmanet al[20]. In the initial treatment of a coccidioidomycosis infection, azole agents are used, and hepatotoxicity is often noted as a common adverse effect[21]. A potential combination of these two pharmacological agents could cause an additive effect on worsening liver function, thereby requiring therapy modification. Additionally, glucocorticoids, that have shown promising results in the Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial, might require reconsideration in SARS-CoV-2 infection with concomitant fungal infection[22].

CONCLUSION

This case highlights the presence of concomitant infection of SARS-CoV-2 and coccidioidomycosis, complicated by refractory pneumothorax. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second reported case of SARS-CoV-2 and coccidioidomycosis and the first co-infection case to report a complication of refractory pneumothorax.Fungal infections in COVID-19 patients appear underdiagnosed and tends to be more prevalent in patients noted to have ARDS, underlying malignancy, diabetes, chronic lung disorders or prolonged course of corticosteroids. A high index of suspicion should be maintained for co-infection or superinfection of COVID-19 with fungal infection in such patients.