Neonatal infratentorial subdural hematoma contributing to obstructive hydrocephalus in the setting of therapeutic cooling: A case report

2021-09-29LeeRousslangElizabethRooksJarenMeldrumKristopherHootenJonathanWood

Lee K Rousslang, Elizabeth A Rooks, Jaren T Meldrum, Kristopher G Hooten, Jonathan R Wood

Lee K Rousslang, Jonathan R Wood, Department of Radiology, Tripler Army Medical Center,Medical Center, HI 96859, United States

Elizabeth A Rooks, Department of Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708, United States

Jaren T Meldrum, Department of Radiology, Alaska Native Medical Center, Anchorage, AK 99508, United States

Kristopher G Hooten, Department of Neurosurgery, Tripler Army Medical Center, Medical Center, HI 96859, United States

Abstract BACKGROUND Symptomatic neonatal subdural hematomas usually result from head trauma incurred during vaginal delivery, most commonly during instrument assistance.Symptomatic subdural hematomas are rare in C-section deliveries that were not preceded by assisted delivery techniques. Although the literature is inconclusive,another possible cause of subdural hematomas is therapeutic hypothermia.CASE SUMMARY We present a case of a term neonate who underwent therapeutic whole-body cooling for hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy following an emergent C-section delivery for prolonged decelerations. Head ultrasound on day of life 3 demonstrated a rounded mass in the posterior fossa. A follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging confirmed hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and clarified the subdural hematomas in the posterior fossa causing mass effect and obstructive hydrocephalus.CONCLUSION The aim of this report is to highlight the rarity and importance of mass-like subdural hematomas causing obstructive hydrocephalus, particularly in the setting of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy and therapeutic whole-body cooling.

Key Words: Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy; Neonatal subdural hematoma; Therapeutic hypothermia; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Perinatal symptomatic subdural hematomas (SDH) are rare. They most commonly occur in the posterior fossa and are classically thought to result from venous disruption caused by birth trauma[1,2]. Although there are case reports of neonatal SDH after spontaneous vaginal delivery, or in-utero, it is still rare to observe a symptomatic SDH following an atraumatic C-section[3,4]. Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) has recently emerged as a potential cause of SDH, but the evidence is unclear and debated, with much of it based on autopsy[5-8]. Therapeutic hypothermia also appears to contribute to SDH, and whole-body cooling has been shown to impair hemostasisin vivo[9]. Additionally, Wanget al[10] recently reported a case of therapeutic cooling that is thought to have led to a massive SDH.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to date of a neonate who developed a mass-like subdural hemorrhage of the posterior fossa while undergoing whole-body cooling causing obstructive hydrocephalus, following a nontraumatic C-section delivery.

CASE PRESENTATION

Personal and family history

A boy was born at 38 wk and 5 d to a gravida 3, aborta 2 motherviaemergent Csection for prolonged decelerations and arrest of descent which was thought to be related to maternal difficulty in coordinating pushing efforts with contractions while receiving epidural anesthesia. The decelerations did not respond to changes in maternal positioning, or administration of supplemental oxygen and intravenous fluids. The mother had no pre-existing conditions, and was up to date with all vaccinations. His prenatal course was completely normal, including a 20-wk anatomy scan demonstrating normal brain imaging. Thick meconium was present at delivery, which was otherwise uncomplicated.

Physical examination

His birth weight was 4.0 kg, with APGAR scores of 11, 35, 410, and 615. At birth he was apneic, with a heart rate < 60, requiring chest compressions and intubation. Shortly after intubation he developed pulmonary hemorrhage and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure that responded well to endotracheal epinephrine. His respiratory issues were thought to be caused by the aspiration of the thick meconium.

Laboratory examinations

Immediately after birth, his international normalized ratio (INR) was 2.3, with prothrombin time of 25.6 s, activated partial thromboplastin time of 65 s, and platelets of 81 × 103platelets/uL. To correct his coagulopathy, he was given platelets,cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma for hemostasis, with downtrend in INR to 1.0 and uptrend in platelets to normal levels (> 150 × 103platelets/uL) over the next four days.

Imaging examinations

Head ultrasound (HUS) on the first day of life (DOL) demonstrated left grade 1 germinal matrix hemorrhage, but no other intra-cranial hemorrhage. The patient was then started on whole-body cooling for HIE.

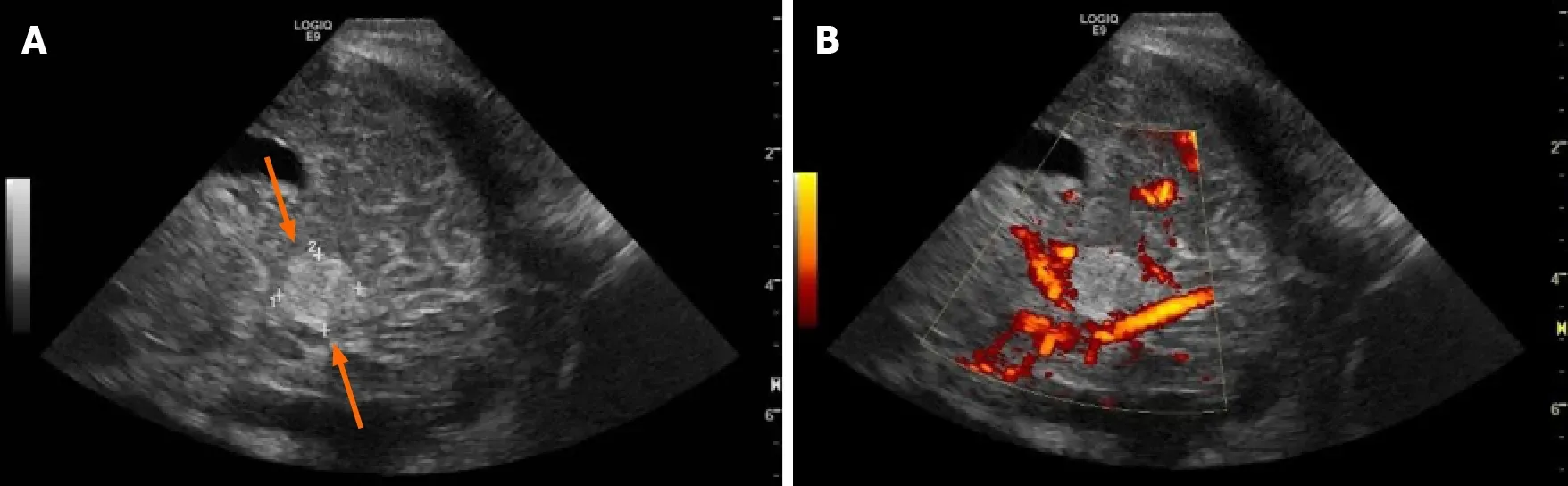

On his fourth day of whole-body cooling, the patient was found to have an increasing head circumference, increasing fontanelle size and fullness, and apneic events, suggestive of obstructive hydrocephalus. His exam further revealed a poor gag reflex and diminished response to stimuli with decreased spontaneous movement.Head ultrasound demonstrated a newly visualized mass in the infratentorial region,thought to represent a cerebellar or tentorial hemorrhage (Figure 1) and the patient was re-warmed.

Figure 1 Head ultrasound through an oblique posterior parietal approach on 3rd day of life. The figure demonstrates an echogenic mass (arrows) in the posterior fossa, inferior to the tentorium, measuring 1.2 cm in its greatest dimension (A) with flow in the straight sinus and lack of flow on power Doppler within the mass (B).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

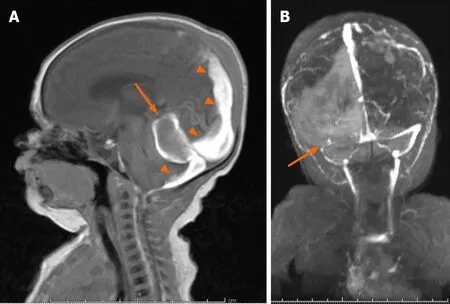

A same-day brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, revealing a 2.5 cm hematoma in the posterior fossa causing extensive mass effect on the cerebellum,and effacement of the fourth ventricle leading to an obstructive hydrocephalus. There was also widespread hypoxic ischemic injury (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A ventricular access device was placed that day for intermittent cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion.

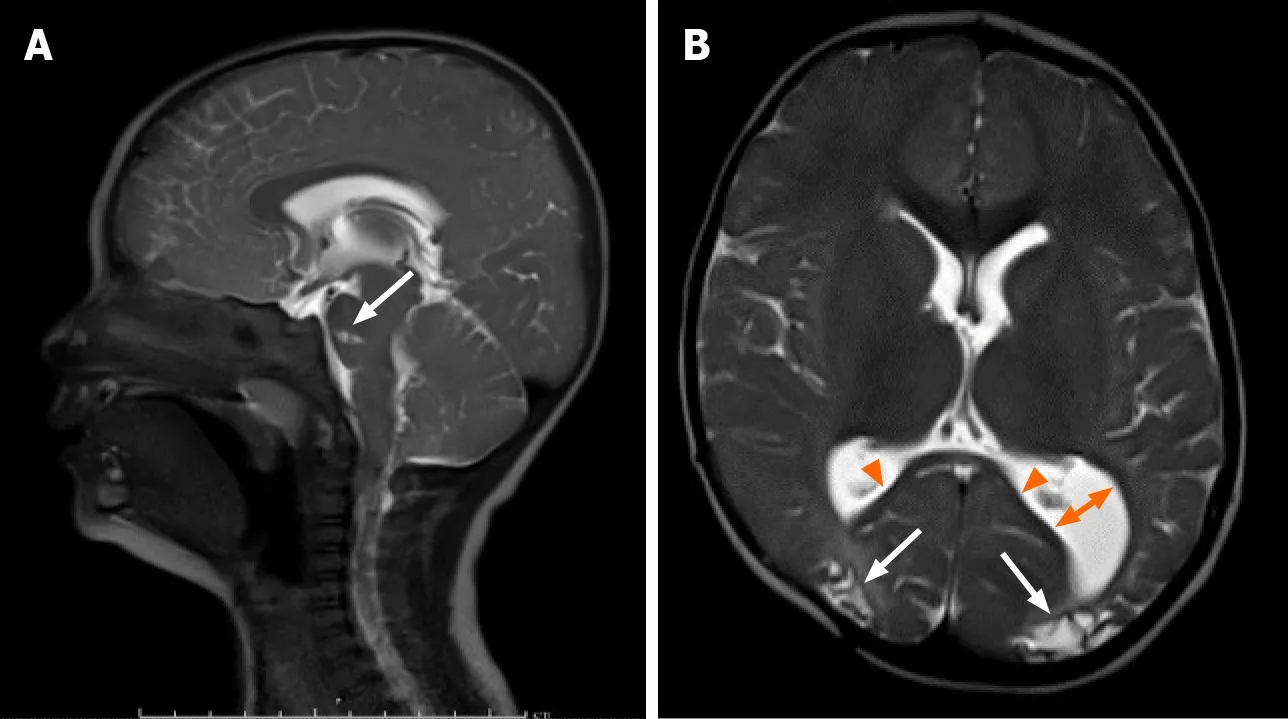

On DOL 20, due to an increase in apneic and bradycardic episodes, and increasing hydrocephalus on HUS, a repeat MRI was performed, and demonstrated acute on chronic bleeding into the subdural space (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Brain magnetic resonance imaging on 10th day of life. A: Follow-up brain magnetic resonance imaging on 10th day of life re-demonstrates the posterior fossa mass (arrow), with interval high signal on sagittal T1 consistent with evolving blood products, as well as persistent subdural hematoma (arrowheads);B: PA coronal MRI venography demonstrates absent flow in the transverse sinus consistent with transverse sinus thrombosis.

Figure 4 Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging on 20th day of life. A: Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging on 20th day of life revealed evolving blood products (orange arrows) in the subdural space on axial T2, with interval left greater than right cystic encephalomalacia in the parietal and occipital lobes and left greater than right ex-vacuo dilatation of the lateral ventricles (two direction arrow); B: Coronal T1 demonstrates degrading blood product in the right temporal lobe subdural space, and central and peripheral infratentorial subdural spaces (orange arrows) with cortical laminar necrosis (arrows) and increasing obstructive hydrocephalus (two-direction arrow).

TREATMENT

Later on DOL 20, the patient underwent successful supratentorial burr-hole evacuation of the subdural hematoma as well as a sub-occipital craniectomy with an infratentorial, supracerebellar evacuation of the thrombus.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

Post-operative imaging demonstrated near complete resolution of the subdural hematoma (Figure 5). MRI at 15 mo of age (Figure 6) demonstrated improved hydrocephalus. At the time of submission, the patient is 29 mo old, and suffers from right spastic hemiplegic cerebral palsy, an expressive aphasia, and strabismus.

Figure 5 A sagittal T1 magnetic resonance imaging done immediately after subdural hematomas evacuation demonstrates near complete resolution of the subdural hematomas (arrow) and resolution of the obstructive hydrocephalus.

Figure 6 Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging at 15 mo. A: Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging at 15 mo demonstrates continued resolution of the subdural hematomas and obstructive hydrocephalus on sagittal T2. Note the focal encephalomalacia at the pons (arrow); B: Axial T2 demonstrates encephalomalacic change manifested by thinning of the posterior corpus callosum (arrowheads), decreased gray and white matter of the posterior occipital regions bilaterally (arrows),and colpocephaly of the left lateral ventricle (two direction arrow).

DISCUSSION

While asymptomatic SDH are commonplace after delivery, symptomatic SDH are rare in neonates, with an incidence of approximately 3.8-5.2 of 10000 Live births[11-13].SDH typically occur in the posterior fossa and are thought to arise from head trauma during vaginal delivery[1,2]. Infratentorial SDH most commonly results from falx or tentorial tears with bridging vein disruption and are worrisome because of their propensity to cause obstructive hydrocephalus, even with small volume bleeds[2].Elective C-section deliveries are rarely associated with symptomatic SDH, likely due to lower rates of birth trauma.

Many researchers have conjectured that SDH can be secondary to cerebral ischemia[5-8]. The prevailing theory is that ischemia leads to damage of immature blood vessels, especially those of the richly vascularized falx cerebri, causing microvascular permeability that leads to intradural hemorrhage (IDH), which is then exacerbated by increased venous pressure[8]. IDH then leads to damage of the weak cell layer between the arachnoid and the dura, causing SDH[8]. However, other smaller studies still debate this theory[14].

The delayed presentation of the SDH in the setting of therapeutic cooling and HIE is what makes this case unique. Our patient’s HIE was likely due to meconium aspiration and pulmonary hemorrhage resulting in asphyxia and acute hypoxemic respiratory failure requiring intubation at birth. The presence of the germinal matrix hemorrhage on initial head ultrasound did not preclude the whole-body cooling protocol from being initiated. Although initial therapeutic hypothermia is not known to cause spontaneous SDH, in-vivo studies have shown that hypothermia can impair hemostasis[15]. Furthermore, many of the studies involved in evaluating whole-body cooling were not powered to assess for harm[10]. Given this case involved a C-section with no significant birth trauma, and a delay in the clinical and radiographic presentation of the hemorrhage, it is likely in this case as Cohenet al[8] suggests that the SDH occurred as a result of cerebral ischemia, and hypothermia exacerbated the condition.

Successful treatment of neonatal posterior fossa subdural hematomas has been reported in the literature as early as 1940. In the largest reported clinical series of 15 infants, Perrinet al[4] demonstrated that successful surgical evacuation of posterior fossa hemorrhages can relieve obstructive hydrocephalus and prevent the need for permanent CSF diversion with good neurologic outcomes. Generally, conservative management is recommended initially but in the presence of hydrocephalus, a worsening clinical exam, or an enlarging hematoma, surgical evacuation should be considered.

CONCLUSION

Screening HUS during hypothermia protocols for HIE warrant scrutiny for hemorrhage in unexpected locations. Symptomatic subdural hematomas warrant a high degree of clinical suspicion, particularly due to their rarity in children delivered by C-section. This report highlights the emerging association of HIE, therapeutic hypothermia, and perinatal intracranial hemorrhage. Prompt imaging and neurosurgical intervention may relieve hemorrhage induced obstructive hydrocephalus during therapeutic cooling with good neurological outcomes,preventing need for permanent CSF diversion. Familiarity with the key imaging characteristics and clinical exam features of mass-like SDH can help the treatment team consider the diagnosis, and potentially enable a prompt recovery.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

杂志排行

World Journal of Radiology的其它文章

- Review on radiological evolution of COVID-19 pneumonia using computed tomography

- Role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis and management of COVID-19 related myocarditis: Clinical and imaging considerations

- Comprehensive literature review on the radiographic findings,imaging modalities, and the role of radiology in the COVID-19 pandemic