The Masks OfKhon

2021-09-13ByLuoTongfang

By Luo Tongfang

COVID-19s impact on tourism threatens the survival of an ancient Thai performing art

The Khon Masked Dance Drama, usually known just as“Khon,”is a performing art popular in Southeast Asia, especially in Thailand. However, the art is not known to many in China. My encounter with Khon was during an adventure in Thailand.

In January 2021, I traveled with a group offellow university students to Cha-Am in ChangwatPrachuap Khiri Khan of Thailand to serve asvolunteer teachers. At midday on the last day of ourjourney, we returned to Bangkok and decided tovisit the Grand Palace in the afternoon sun. WhenI emerged from the palace tour, I was greeted by agirl in an exotic costume. She asked to see my ticketand directed my attention to some glittering figuresprinted on the back of it. I realized it was a coupon for a Khon performance.

I had never heard of Khon nor had any intentions of seeing it. However, the girl with a bright Thai smile insisted I board a beautifully decorated sightseeing bus. I followed her directions and embarked on the mystery trip. I searched the web for Khon and prepared for the show.

Thai Epic Ramakien

I debussed right in front of a theatre, greeted by a tall statue of a divine figure dressed in white and yellow traditional costume with elegant patterns and a gold crown on his head, clasping his hands in a bow. I soon learned that it depicted the main character of the show: Hanuman, the monkey warrior.

Hanuman was the monkey warrior in the Indian Hindu epic Ramayana and enjoys a status in Southeast Asian culture similar to the Monkey King in Chinese culture. In the original Hindu epic, Hanuman helps Rama,the prince ofAyutthaya, in a bitter fight againstRavana, the demon king, who kidnapped his wife Sita. Around the 10th Century, the Hindu epic was introduced to Thailand and evolved over time into Ramakien, the Thai adaptation.

Ramakien is the only script for Khonperformances. It is set in the Ayutthaya Dynasty inThai history. Rama and Sita in the original Hinduepic were translated into Phra Ram and Phra Lak inThai language, while demon king Ravana turned into Thossakhan, the demon of Longa, and the monkeywarrior kept his original name of Hanuman. In theadapted story, Phra Ram and PhraLaksana, princesof the Ayutthaya Dynasty, join forces with Hanuman and other monkey warriors including monkey kingSukreep and PhyaPhali in a heroic fight againstThossakhan to save Phra Lak (Sita). Since Ramakienis a long epic with relatively independent episodes,each show is usually a classical plot such as Phra Lak Kidnapped, Corpses at Sea, Road Through the Sea, andMonkey Warrior Hanuman.

“Chada” and “Mask”

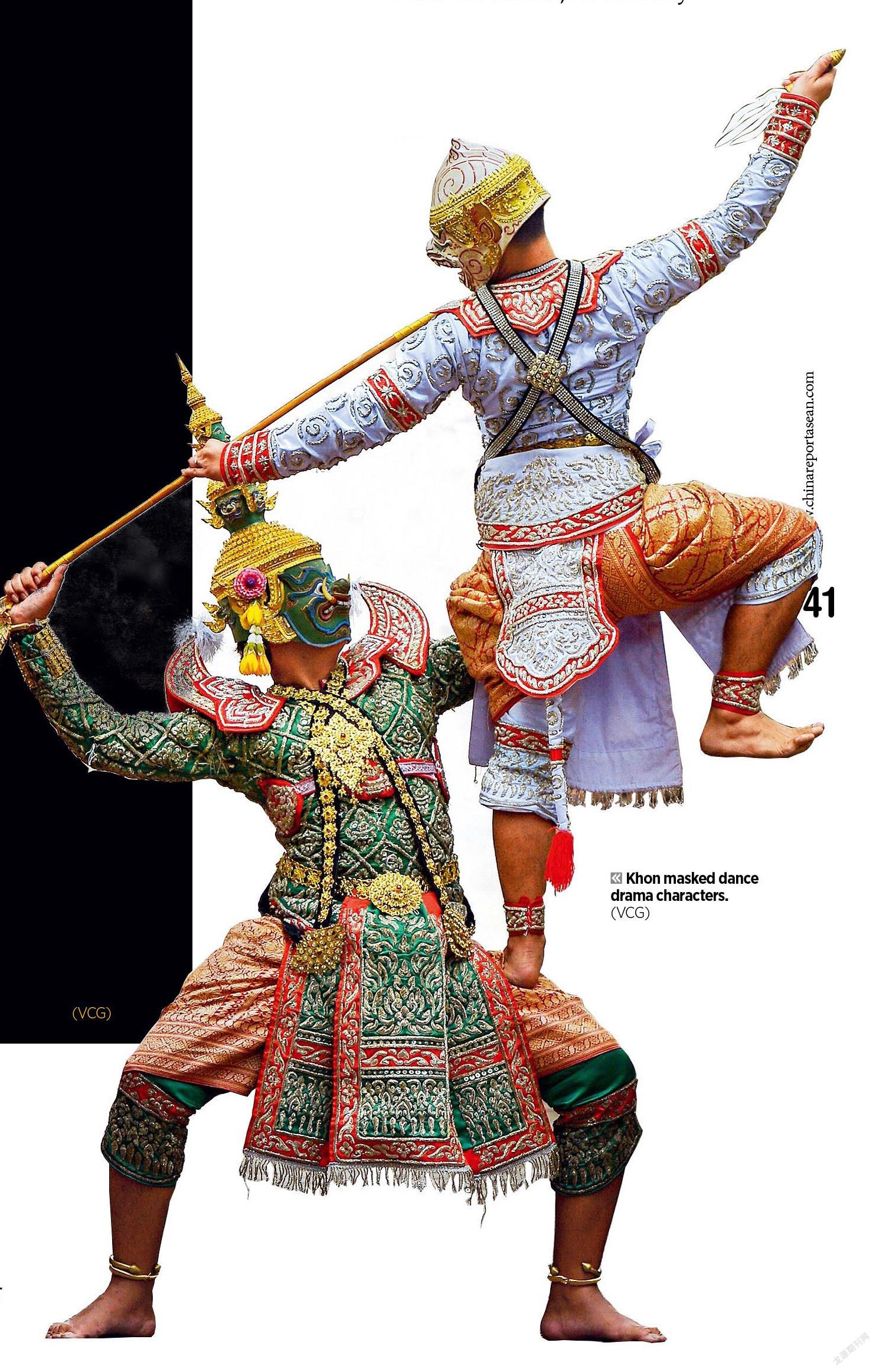

In a pitch-dark theatre, the stage was overtakenby fairies dressed in glittering costumes dancingin groups while some monkey warriors ran andjumped among them with impressive flexibility.Shortly afterwards, groups of demons enteredand confronted the monkey warriors in militaryformations with the support of golden chariots and flags. Some engaged in one-on-one combat.

Members of the royal family and God Brahmawore Chada, golden crowns, instead of masks. Thecrown resembled a circular cone decorated withdiamonds and precious stones, like a pagoda on thehead. Fittingly, the Chada is also known as a“pagodahat.”TheChada is a symbol of nobility. Members ofthe royal family and gods each have special Chadas. Similarly, monkey king Sukreep and demon kingThossakhan also have a unique Chada, while monkey warrior Hanuman has only a flat golden crown.

All of the other characters including demons,monkeys and other animals were wearing masks.Unlike Chinese and Western masks, some of theKhon masks such as those of the demons andmonkeys were spherical and completely coveredthe actorsheads. Some masks, like those of horses,were merely neck and breast decorations. There areover 30 different kinds of masks for monkeys andover 100 kinds of masks for demons. The masks formonkeys are designed with the pattern of a roaringmonkey with big eyes, a red mouth, and curly hair. The masks for demons are designed with the pattern of an angry figure with wide-open eyes and exposedbuck teeth. Since most actors perform behindmasks, Khon is known as“a masked dance drama.”

“Chada”and“mask”represent not only thedifferent roles on the Khon stage, but also thedifferent career stages for Khon actors. I met anactress portraying a fairy with Chada who beganlearning the part when she was seven years old.After 14 years of rigorous practice and rehearsals,she finally made it to the stage last year to officially perform for an audience.

I was surprised that behind the amazing Khonperformance was such boring repetition for so many years. She insisted that one couldnt possibly capture the essence of the fairy without constant practice.She revealed to me that masked Khon actors dontspeak their lines, enabling them to concentrate onthe rhythm of the music, while most of the linesare delivered from backstage. The practice andrehearsals can be boring, but the standards for anoutstanding performance keep her motivated. Sheonly wants to play the role to its perfection. Whenshe retires, she wants to pass on her skills to theyounger generation.

Survival of the Art

The encounter with Khon in Thailand fascinated me. After returning to China, I read books andresearch to better understand the art. I added tomy theoretical knowledge by learning more aboutits history and features. I also learned about theconservation efforts of the Thai royal family andgovernment. Even after I knew more about it, I still felt like Khon was being kept behind an invisiblecurtain barring me from truly appreciating thedevotion of the fairy at the theatre in Bangkok.

Last year, Krich, a Thai exchange student,visited my school. I spoke to him about my Khonexperience in Bangkok and asked if he enjoyed such performances.

“Khon is like Peking Opera in your country,”he said.“I havent ever seen a Khon performancebecause admission was very expensive, like 1,000 baht (US$32), a few years ago. I think only foreigntourists would ever see the shows, which were few because they would prefer scenic spots.”

His response was quite surprising to me.According to my understanding, Thailand hasbeen vigorously promoting performing arts. Theroyal family has hosted many performances forforeign heads of state and government leaders. The government has allocated funds for schools at alllevels to set up Khon projects and Khon troupes to tour the country. In 2018, Khon was inscribed onthe Representative List of the Intangible CulturalHeritage of Humanity, attracting some globalattention. The Consulate-General of Thailand inKunming organized a Khon tour to China by some Thai secondary school students.

Krich wasnt impressed with my persistence.“Khon developed as a royal drama for the royalfamily,”hesaid.“Only a very small number ofschools are able to organize Khon projects. Youd be extremely lucky to see a free Khon show in a localcommunity. Very few people would spend so much money on a theatrical show. Im quite impressedthat you know so much about Khon.”

I could not help but regret hearing his words. Itshows that even support from the Thai royal family and government hasnt produced enough effectiveefforts to promote the art among the general public.

Khon is more popular among the internationalaudience. It was reported that due to the impact ofCOVID-19 in 2020, the Royal Theatre was concerned its audience would never recover to pre-pandemic levelssince the bulk was foreign tourists, 50 percent Chinese.

The Sala Chalermkrung Royal Theatre, where Iwatched the show, faces a similar situation. To meetthe needs of the international audience, the theatrestaff provide service and plot descriptions in English and Chinese, while most actors can interact withthe audience in English. Traditional Khon drama istediously long. The Thai royal family and NationalTourism Administration tailored a 45-minute“condensed”version for foreign tourists.

Clearly, the arts survival relies heavily oninternational tourism. Although the Thaigovernment has promoted it in schools andcommunities around the country, the survival of the art in the local market has not been easy, especiallyin this post-pandemic era when the recovery oftourism has been sluggish.

Tourists make the price oftheKhon admissiontickets significantly higher than the average priceofcompeting domestic entertainment products,which leads to insufficient market demand.As a royalperforming art, its also a costly business, with the price ofa single costume as high as 50,000 baht (US$1,540). But the Thai general public is not unenthusiastic about traditional art. During my stay at Cha-Am, I personallywitnessed a group ofchildren gathering in front ofa humble curtain to watch a Thai shadow puppetshow. Ifthe ticket price could drop with the help ofmodern technology and some“simplified”version ofthe drama tailored to the general public, it could gainmore popularity domestically, which would inject new impetus into the traditional art.

Like other traditional cultures, Khon facesdifficulties in maintaining vitality in the modern market. Whether to give up important elementsdistant from modern society and whether tointegrate popular elements into the traditional art are tough choices. In the current circumstances,there should be space for compromise.