Centenary Of Modern Archaeology: A Journey to Rediscover China

2021-09-13ByQiuHui

By Qiu Hui

After modern archaeologys 100 years of development in China, the origins of Chinese civilization are becoming increasingly clear

The year 1921 witnessed many epoch-making events in Chinese history. On July 23 of that year, the First National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) kicked off in Shanghai, turning the page on the Chinese revolution. Three months later on October 23, Swedish geologist and archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson and his assistant Yuan Fuli arrived in Yaoshao Village, Mianchi County, central Chinas Henan Province, and started an archaeological excavation there four days later.

The excavation marked the first attempt at archaeological fieldwork in China, which was of epoch-making significance for breaking new ground in exploring ancient Chinese culture. It is widely considered the commencement of modern archaeology in China.

Subsequently, Chinese history recorded in books was repeatedly verified and enriched by numerous archaeological findings. The discovery of the archaeological ruins of Liangzhu City in Zhejiang Province provided irrefutable evidence for claims that the origins of Chinese civilization can be traced back at least 5,000 years. A hundred years have passed since modern archaeology began in China with the excavation of the Yangshao archaeological ruins. The origins of Chinese civilization and the traces of the countrys prehistoric civilization have become increasingly clear thanks to professional archaeological studies.

“Studying ancient civilization can shine light on where we humans came from and where we will go,” declared Wang Wei, president of the Chinese Society of Archaeology.

Origins of Modern Archaeology in China

The Chinese term for archeology, “Kao Gu,” was coined centuries ago. As early as the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), Chinese scholar Lu Dalian penned Kao Gu Tu (Archaeological Illustrations), an archaeological monograph on bronze wares and stone carvings.

Andersson introduced modern archaeology toChina 100 years ago. A world-renowned geologist,he was hired by the Chinese government as a mining advisor to search for mineral resources in China. He was a member of the Chinese Institute of Geology,one of the earliest scientific research institutions in modern China.

In 1920, his assistant Liu Changshan reportedthe results of the early field investigations inYangshao to Andersson. Later, Andersson appliedfor permission from the government to conduct an archaeological excavation of the ruins in the village. Upon examinations by governments at severallevels, his application was officially approved. Itwas Chinas first archaeological excavation projectcarried out at international standards with fullgovernmental approval.

The year after the approval, Andersson joinedChinese scholars including Yuan Fuli in conducting the first-ever excavation of the Yangshao ruins. His team unearthed a large amount of stone objects and painted pottery pieces. Relics were later dated to the Neolithic Age.

The Neolithic ruins in Yangshao Village werethus named Yangshao culture. The project featuringarchaeological fieldwork and excavation heralded the beginning of modern archaeology in China.The Yangshao culture, well-known for itspainted pottery, dates back to the prehistoricperiod from 5,000 B.C. to 3,000 B.C. It wascentered around the areas in centralShaanxi, western Henan, and southern Shanxi where the branches of theYellow River such as Weihe, Fenhe,and Luohe meet, extending to the Great Wall and the Hetao region in the north,to northwestern Jiangxi Province in thesouth, to eastern Henan Province in the east,and to the border between Gansu and Qinghai provinces in the west.

According to Wang Wei, Andersson and his team incorrectly hypothesized that painted pottery wasintroduced to China via West Asia due to the lackof archaeological findings in China at the time. Thelack of surrounding evidence even resulted in a“hypothesis”that Chinas prehistoric culture camefrom the West. To refute the hypothesis, numerousChinese scholars became devoted to archaeologicalstudies in hopes of finding hard evidence supporting the prehistoric origins of Chinese civilization.

In 1926, Li Ji, a Ph.D. in anthropology, returned toChina after finishing his studies in the United States. He joined hands with the U.S. Freer Gallery ofArt toconduct a field investigation in southern Shanxi and led a team to excavate the prehistoric ruins in XiyinVillage. His purpose was clear: find evidence proving the connection between prehistoric painted potteryand Chinese culture.

This marked the first attempt made by Chinese scholars to explore ancient Chinese history through archaeological means. Chinese writer Dai Jun wrote in The Biography of Li Ji: “The excavation of the prehistoric ruins in Xiyin Village was the first program of archaeological fieldwork presided over by the Chinese, which marked the beginning of modern archaeology in China and crowned Li Ji as ‘the father of Chinas modern archaeology.”

In 1927, a research academy named “Academia Sinica” was established, with Cai Yuanpei as its president. The academy later set up the Institute of History and Philology (IHP), of which the Division of Archaeology was the most important.

In 1928, the IHP launched an archaeological excavation of the Yin Ruins. In the spring of the following year, Li Ji was appointed head of the institutes Division of Archaeology to oversee the excavation project after he returned from archaeological fieldwork in places like Xiyin Village. The project was the first archaeological excavation organized by a Chinese academic institution.

The First “Golden Age”

Over the following decade-plus, the IHP organized 15 excavations of the Yin Ruins in the northwestern suburb of Anyang, Henan. Later excavations were overseen by Liang Siyong, a son of Liang Qichao (renowned philosopher and a leader of the Reform Movement of 1898). Liang Siyong improved the organization and methods for archaeological fieldwork, making it more professional.

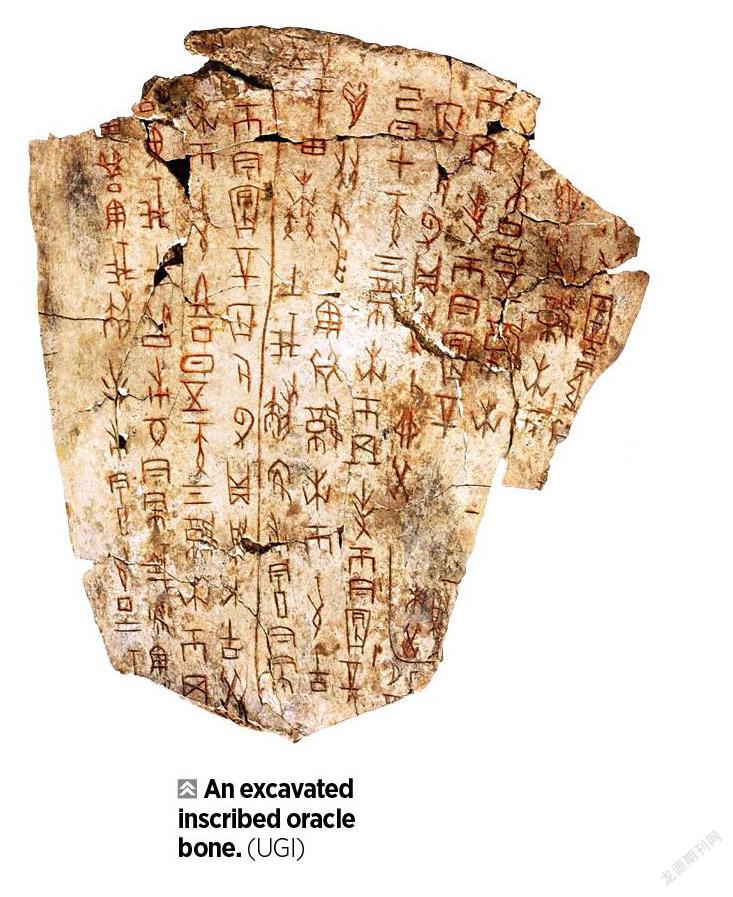

From Pit YH127, archaeologists unearthed many precious cultural relics, including the bronze Houmuwu ding (sacrificial vessel) as well as 17,000 animal bones and tortoise shells with oracle inscriptions. The oracle inscriptions carry information about the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), providing hard evidence for historical records about the ancient regime. The findings also made some legends about the Shang Dynasty become true history.

In the eyes of Wang Wei, the period from 1921 to 1937 marked the first “golden age of archaeology” in China. During the period, all archaeological investigations and excavations aimed to search for “the roots of Chinese culture.” Wang pointed out that alongside oracle bone inscriptions, the 1928 excavation of the Yin Ruins also unveiled plentiful information about Chinese society during the Shang Dynasty. Seeking historical evidence through both literary research and archaeological excavation gradually became an approach widely accepted by academia.

It is widely recognized that the excavations of the Yin Ruins and the research of oracle inscriptions aunched a new method for Chinese people to understand history: verifying and complementing historical documents while shining light on what is missing from them. Before that, history studies were mainly based on ancient books and limited amounts of inscriptions found on ancient bronze wares and stone steles.

Despite the emergence of this new method, archaeology remained in its infantry in China during the 1920s. Chang Huaiying, an associate research fellow at the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), argued in an article that although the historical period of the Yin Ruins has been confirmed, the pottery pieces, stone objects, and other relics unearthed in the 1928 excavation were so fragmented due to the outdated, non-standard excavation techniques at that time that they can hardly be used for academic studies.

The Yin Ruins were the remnants of the capital of the late Shang Dynasty. Inspired by findings at the Yin Ruins, archaeologists were eager to use the same method to corroborate records about the Xia Dynasty (2100-1600 B.C.) in historical documents, especially Records of the Grand Historians by Sima Qian of the Western Han Dynasty (202 B.C.-8 A.D.)

Professor Sun Hua from the School of Archaeology and Museology at Peking University explained that archaeologists basically figured out the main course of the development of Chinese culture along the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, from the Zhoukoudian Peking Man Ruins dating back hundreds of thousands of years to the Yangshao culture 5,000 to 6,000 years ago, the Longshan culture 4,000 to 5,000 years ago, and the Shang Dynasty culture 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.

Archaeology as an Academic Discipline

In 1937, the war of resistance against Japanese aggression broke out nationwide. In 1945, China fell into a civil war. During the period, social turmoil left archaeologists few chances to carry out effective research work.

A major breakthrough in this period was the “Yangshao-style painted pottery” unearthed by archaeologist Xia Nai in the tombs of the Qijia culture in Yangwawan, in Ningding County, Gansu Province. The finding ended the hypothesis that “prehistoric Chinese culture came from the West.” Before that, the hypothetical theory had haunted Chinese academia for more than 20 years.

Chinese scholar Chang Huaiying noticed that during that period, archaeological fieldwork concerning ruins of historical periods other than the Xia, Shang, and Zhou (1046-256 B.C.) dynasties was far from “systematic,” and that archaeologists paid inadequate attention to the cultural diversity of new findings.

When reviewed by the media, Zhao Hui, vice president of the Chinese Society of Archaeology, said that Chinese archaeology remained at its fundamental stage before 1949. Chinese archaeologists and relevant scholars tried to trace the cultures of the Xia and Shang dynasties and even earlier periods based on existing clues while at the same time working to improve the use of foreign archaeological techniques and methods in China.

In 1950, shortly after the founding of the Peoples Republic of China in 1949, the Institute of Archaeology under the Chinese Academy of Sciences was established. Xia Nai served as its third president. Alongside large-scale construction around China, countless underground ruins were unearthed. A major task for Chinese archaeologists at that time was to preventcultural relics from being lost to construction, whichis known as“rescuearchaeology.”The Institute ofArchaeology sent archaeological teams to the ruinsof ancient capital cities, including Fenggao City ofthe Western Zhou Dynasty (1046-771 B.C.), ChanganCity of the Western Han Dynasty, Changan City ofthe Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties, thecapital city of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-256B.C.), Luoyang City of the Eastern Han (25-220) andWei (220-280) dynasties, and Luoyang City of the Suiand Tang dynasties, to help protect cultural relicsunearthed during construction projects.

Back then, China suffered a shortage ofarchaeological personnel. To solve the problem,the country began to strengthen archaeologyeducation. In 1952, the Department of History atPeking University was established as the first to offerarchaeology courses in China and has since trainedmany archaeological professionals.

In 1953, Xia Nai, then president of theInstitute ofArchaeology, proposedfocusing on archaeologicalresearch of the Neolithic Age andthe Shang and Zhou dynasties,especially the Western Zhouperiod, while unearthing andsorting out cultural relics alongsidethe national construction projects. Healso called for learning from the SovietUnion to carry out large-scale systematicexcavations and conduct archaeologicalresearch with natural science methods.

Unveiling the Early History of China

According to Wang Wei, from 1949 to 1966,archaeological work in China proceeded along withthe countrys economic development. Unlike before,archaeological excavations during this period wereno longer confined to a few sites, but expanded toareas along the Yangtze and Yellow rivers. He calledthis period the preliminary development stage ofChinese modern archaeology.

The biggest outcome during the period wasexcavation of the Erlitou Ruins. In 1959, Chinesearchaeologist Xu Xusheng, among the first returnedChinese students from France, led a team on a fieldinvestigation of the capital city of the Xia Dynasty inwestern Henan. They discovered the Erlitou Ruinsduring the trip.

The discovery consolidated archaeologistsconfidence in delving into the history of the XiaDynasty. Afterwards, archaeologists carried outdozens of excavations there, resulting in a series ofsignificant findings. In 1977, Xia Nai named the newarchaeological discovery the Erlitou culture.

Because of a lack of confirmed textual evidence,debates on whether the Erlitou culture belonged to the Xia Dynasty or whether the ruins were formerly the Xia capital continued until the late 1980s when both were confirmed. From then on, the Xia Dynasty was included in archaeological research formerly focused on the Shang and Zhou dynasties.

Wang Wei talked about the establishment of the Xia Dynasty in an article titled “The Program of Tracing the Origins of Chinese Civilization I Experienced.” “Research results show that various regional civilizations exchanged, absorbed, learned from and integrated with each other, resulting in the formation of Chinas first dynasty—the Xia—about 4,000 years ago,” he wrote.

Cao Bingwu, a Chinese scholar who has long been dedicated to archaeological research, pointed out in an article that the Yangshao culture laid the foundation for the formation of the Chinese nation and Chinese civilization and that Chinas basic cultural connotations such as demology, language, and agricultural economics were already set by then. The Erlitou culture, in fact, realized the integration and breakthroughs of different tribes and crosscultural elements and formed a nation and cultural community that transcended the boundaries of bloodline-based tribes, basically setting up the framework of Chinese civilization.

The Second “Golden Age”

During the 1980s, Xia Nai, then president of the Institute of Archaeology, CASS, visited Japan six times to give speeches. This marked wider academia officially starting to research the origins of Chinese civilization.

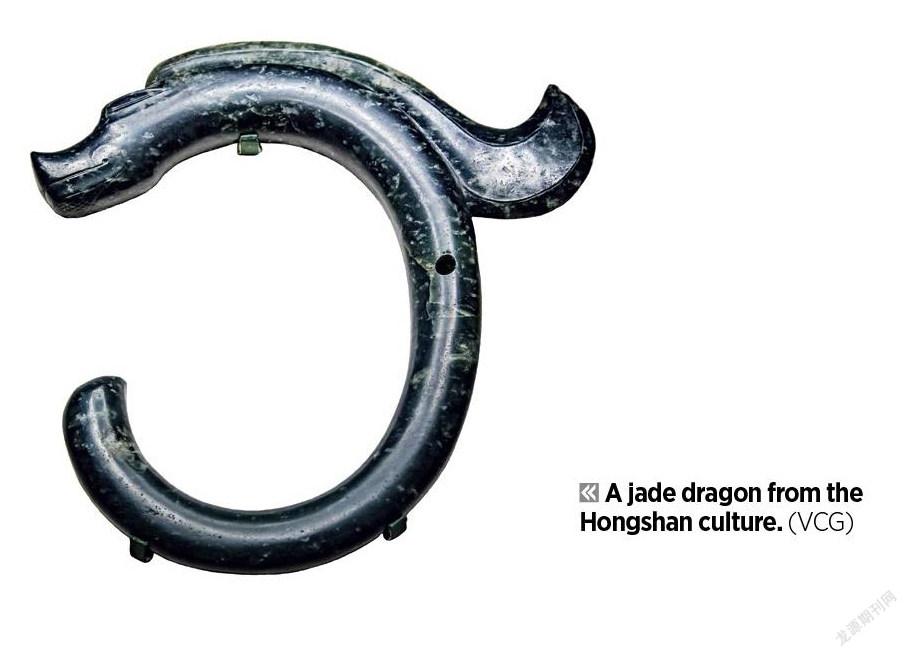

According to Wang Wei, excavation of the Yangshao culture made the Central Plains region considered the center of the origins of Chinese civilization. However, in the first half of the 1980s, archaeologists discovered many prehistoric ruins beyond the Central Plains, and major breakthroughs were made in tracing the origins of Chinese civilization. Researchers found that the Hongshan culture in the Xiliao River Valley had already fostered a prosperous civilization and obviously stratified society about 5,000 years ago. Exquisite jade wares and tombs with plentiful jade and stone burial objects were unearthed from the Liangzhu ruins in the lower reaches of the Yangtze River. These findings indicate that those areas had cultural prosperity that wasnt inferior to the Central Plains in the same period.

Then, Chinese archaeologist SuBingqi posited that Chinese civilization didnt originate in any single place, but regional cultures as numerous as stars in the sky contributed to its formation. Thisexplained the complexity and diversity of ancient Chinese culture.

Su divided the vast land of China into six zones, each with an independent origin and development trajectory of its regional civilization. The Central Plains region is just one of them. He pointed out that the Central Plains didnt become the center until the Xia and Shang dynasties when it absorbed other regional civilizations through exchanges and integration. This “pluralistic integration” theory provides a core framework to understand the origins of Chinese civilization. Later theories such as “regional categorization” and “multi-petal flower” are just derivatives of the aforesaid theory.

During the period, numerous archaeological findings emerged alongside Chinas economic growth. According to Professor Sun Hua, archaeology saw rapid development in China after the 1950s and entered another “golden age” in the 1980s.

A large number of cultural relics were rescued, and huge amounts of historical data and information were accumulated. Moreover, according to Sun, the chronological framework of Chinese archaeology and archaeological findings gradually improved, and a basic pedigree on the evolution of Chinas tangible cultures was formed as different regions established respective archaeological sequence systems and the government launched the XiaShang-Zhou Chronology Project. This laid a solid foundation for further exploring historical elements such as human behaviors, social relations, and forms of state behind those tangible cultures.

Furthermore, Chinese archaeologists realized remarkable achievements in the research of such important topics as the origins of ancient humans in China, the proliferation and distribution of homo sapiens, the origins and spread of agriculture and relevant cultural elements, the evolution of ancient social systems, the complexity of ancient Chinese society, and the formation of state.

Understanding Chinese Civilization through Archaeology

In 1990, the Institute of Archaeology, CASS, organized a civilization origin research team to delve into the origins of civilizations of different periods. However, they failed to completesystematic research. In 2000, a group of scholars including Wang Wei proposed launching a project to study the origins of Chinese civilization.

Wang noted that the project focused onresearch of the formation of Chinese civilization.“It aimed to study how Chinese civilizationwas formed, how diverse regional civilizationsinteracted and integrated with each other, andhow the Central Plains became the center, ratherthan which year or where Chinese civilizationoriginated,”he illustrated.

In the late 1990s, Wang led the archaeological excavation of the Shang Dynasty palace cityin Yanshi District of Luoyang City, Henan.The excavation unveiled the ruins of a palacecomplex from the early Shang Dynasty with three courtyards, the first of its kind ever unearthed.

Wang said that archaeology has seentremendous changes since the beginning of the 21st Century and that many new archaeological findings have drawn great public attention.In 2020, a new excavation was carried out atSanxingdui Ruins that represented ancient Shu culture. The excavation was livestreamed online for the first time.

To Wangs surprise, the livestream received 7.1 billion views. He noted that the public has shown greater interest in cultural products alongside the improvement of their living standards. To cater to their needs, it is important to make cultural relics come “alive” and share their stories with the public. Wang suggested cultural heritage workers disseminate relevant knowledge in an easyto-understand way to ensure ordinary people can soak up the glory and charm of Chinese civilization through understanding the cultural relics left by their ancestors and enhance their confidence about Chinese culture. Wang called the recent excavation at the Sanxingdui Ruins a good example of archaeological studies and education, which helped build archaeology with Chinese features, style, and ethos.

“Archaeology plays an irreplaceable role inhistory studies and makes tangible contributions to helping Chinese people better understandtheir civilization and consolidate culturalconfidence which in turn enhances Chinasinternational influence,”Wang said.