Dynamic changes in the systemic immune responses of spinal cord injury model mice

2021-09-01WenQingWangLiuDiWangDanMu

Wen-Qing Wang Liu-Di WangDan Mu

Abstract Intraspinal inflammatory and immune responses are considered to play central roles in the pathological development of spinal cord injury.This study aimed to decipher the dynamics of systemic immune responses, initiated by spinal cord injury. The spinal cord in mice was completely transected at T8. Changes in the in vivo inflammatory response, between the acute and subacute stages, were observed. A rapid decrease in C-reactive protein levels, circulating leukocytes and lymphocytes, spleen-derived CD4+ interferon-γ+ T-helper cells, and inflammatory cytokines, and a marked increase in neutrophils, monocytes, and CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T-cells were observed during the acute phase. These systemic immune alterations were gradually restored to basal levels during the sub-acute phase. During the acute phase of spinal cord injury, systemic immune cells and factors showed significant inhibition; however, this inhibition was transient, and the indicators of these serious disorders gradually returned to baseline levels during the subacute phase. All experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional animal care guidelines, approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Experimental Animal Center of Drum Tower Hospital, China (approval No. 2019AE01040) on June 25, 2019.

Key Words: C-reactive protein; immune dysfunction; inflammation; inflammatory cytokines; regulatory T-cells; spinal cord injury; systemic immune response; T-helper cells

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a refractory neurological disorder with no breakthrough therapy currently available. SCI is commonly characterized by primary and secondary injuries(Garcia et al., 2016). Initially, mechanical insults, such as trauma, directly cause a primary injury. Secondary injuries can be derived from a plethora of pathological changes, overtime, including vascular damage, demyelination, in flammatory responses, metabolic disorders, and excitotoxicity. Intraspinal inflammatory and immunity responses are considered to play central roles in the evolving pathological development and coordination of various secondary injury mechanisms,which exacerbate clinical neurological deficits (Kwon et al.,2004; Allison and Ditor, 2015; Faden et al., 2016; Brennan and Popovich, 2018).

Intraspinal in flammation elicited by SCI has been well studied,and the in flammatory response that follows SCI is a smoldering and non-self-limiting inflammatory cascade, orchestrated by a series of different cell types, including infiltrating immune cells, microglia, astrocytes, and endotheliocytes (David et al.,2018). Infiltrating immune cells have been demonstrated to act as major contributors to the intraspinal cord in flammatory responses elicited by SCI (Allison and Ditor, 2015). Leukocytes in the peripheral blood are recruited to injured sites, in a timedependent manner, by the early immune response following SCI (Mietto et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2018). Monocytes and neutrophils have been observed to infiltrate the injury and surrounding areas, attracted by the cytokines and chemokines that are released, first from glial cells and, subsequently,from endothelial cells. Infiltrated peripheral immune cells and endogenous microglia respond synergistically to SCI (Orr and Gensel, 2018). Different immune subsets have distinct effects on neuroprotection or neurotoxicity, or both; thus, SCI recovery depends on the various interactions among these subset populations (Kipnis et al., 2002; Mege et al., 2006;Kigerl et al., 2009; Thawer et al., 2013; Järve et al., 2018).Although several types of immune cells have been identi fied to participate in recovery processes after SCI (Schwab et al.,2014), we do not yet fully understand their temporal and spatial regulation, the associated cellular and molecular mechanisms, or the interrelationships that occur among these cell types.

Normally, the peripheral immune response is vital to the maintenance of spinal cord homeostasis. SCI causes dysfunction or losses in the vegetative innervation of endocrine and lymphatic tissues, resulting in long-lasting,aberrant inflammatory responses (Zhang et al., 2013). The local immune response associated with SCI can affect the systemic immune response, which, in turn, influences both the pathophysiological changes that occur in the injured area and the repair process. Existing “compartmentalized” studies have primarily focused on limited intraspinal inflammation and immunity and the associated cellular or molecular mechanisms that occur in the spinal cord. Although systemic immune activity affects the central nervous system (CNS),beyond the compartmentalized in flammatory responses that occur in the spinal cord, which can influence the recovery of tissue structures and motor function following SCI,these effects have been less well characterized than those associated with intraspinal inflammation (Popovich and McTigue, 2009).

CD4+T-helper cells play critical roles in proper host defenses and normal immune-regulation, differentiating into functionally distinct T-helper subsets (Abbas et al., 1996;Murphy and Reiner, 2002). CD4+CD25+forkhead box P3(FOXP3)+regulatory T-cells (Tregs) represent an important T-cell subset with an indispensable role in the maintenance of immune tolerance and the suppression of excessive detrimental immune reactions by the host (Popovich and McTigue, 2009; Nakayamada et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013).Various subsets of in filtrating immune cells play speci fic roles in neurotoxicity and neuroprotection, and the recovery of CNS damage may depend on the balance among these subtypes(Hu et al., 2016). These subsets affect the pathophysiology of SCI through the release of cytokines and growth factors, which act as signaling proteins. The balance between the pro- and anti-in flammatory effects mediated by these molecules plays a key role in the progression and prognosis of SCI lesions (Garcia et al., 2016). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6 are critical mediators of inflammatory reactions, whereas IL-10 has multiple effects on immune regulation and in flammation, and can inhibit the effects of pro-in flammatory cytokines produced by macrophages and Tregs. Additionally, IL-10 can also act on Tregs to maintain the expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 (Rubtsov et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2016).

The dynamic interactions between CNS-innervated peripheral immune organs and the immune-privileged spinal cord,therefore, must be examined to accurately evaluate the evolving state of SCI. In this study, we surveyed changes in the systemic immune system, over time, following SCI. We revealed an integral spectrum of systemic immune responses that are initiated by SCI, providing further understanding of the pathophysiological process that occur after SCI, and revealing targets for the future immunotherapy of SCI.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Thirty speci fic-pathogen-free, female, C57BL/6 mice, weighing 20-25 g and aged 8 weeks old, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories [Jiaxin, Zhejiang Province, China; license No. SCXK (Zhe) 2019-0001] and were housed the animal facilities of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, with food and waterad libitum, in a 12-hour light/dark cycle. All experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional animal care guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Experimental Animal Center of Drum Tower Hospital, China (approval No. 2019AE01040) on June 25, 2019.

SCI surgery

SCI was established according to the previously reported protocols, with minor modifications (Schwab et al., 2014;Kullmann et al., 2019). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 5% iso flurane (VETEASY, RWD Life Science Co., Ltd., Shenzhen,China; 1.5-2% [v/v] in O2) in Matrx Animal Aneathesia Ventilator System (VMR, MIDMARK Corporation, Torrance,CA, USA). A laminectomy was performed, between the T8-9 vertebrae, and the spinal cord was completely transected.The sham animals were exposed in the same manner, but the spinal cords were not damaged. Gelfoam was placed above the spinal cord, to achieve hemostasis. The muscle and skin were closed with absorbable sutures (Vicryl, 3-0, Ethicon Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). The animals received 200 µL prewarmed saline, through intraperitoneal injection, and were allowed to recover on a heating pad, for 3-6 hours. Animals were intraperitoneally injected with ceftriaxone sodium (50 mg/kg, drug license No. H20043014; Youcare Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., Corona, CA, USA), to prevent infection,once per day, for 3 days. The bladders of mice with SCI were manually voided twice during the entire experiment.

Complete blood count

After euthanasia, approximately0.5 mL blood was collected from the cephalic vein, in syringes containing [K2]-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. Complete blood count analysis was performed, using an automated hematology machine (COULTER® LH 750, Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL,USA), including erythrocyte counts and three-part differential(lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils), as well as a series of erythrocyte parameters. Complete blood count was performed 0, 3, 5, 7, and 14 days after SCI.

C-reactive protein measurement

The quantitative measurement of C-reactive protein (CRP) in mouse plasma was performed 0, 3, 5, 7, and 14 days after SCI,using a commercial mouse CRP enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (SEKM-0059; Solarbio, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma samples were diluted to 1:2000, and 100 µL of the diluted sample was added to separate antibody-coated microplate wells. A 100-µL volume of the urea peroxide substrate, 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine as the chromogen was added to each well to initiate color development. The reaction was interrupted with a stop solution, and absorbance was detected with a microplate reader (#237062; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) at 450 nm.Quanti fication was performed using a standard curve, which was generated by measuring serial two-fold dilutions of the standard provided with the kit.

Splenocyte preparation

Mice were anesthetized with 1.25% tribromoethanol, and then the spleens were removed and ground. A single-splenocyte suspension was obtained by passing the ground tissue through a 100-µm wire mesh. The viability of the freshly collected single-splenocyte suspension was verified with trypan blue staining, which demonstrated cell viability greater than 99%. A total of 2 × 105cells were suspended in individual tubes and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (GibcoTMCat# 12633012; Life Technologies Co., Carlsbad, CA, USA),supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cat# 10099141;Life Technologies Co.), 100 U/mL of penicillin, 100 µg/mL of streptomycin (Cat# 10378016; Life Technologies Co.), and 2.5µL T-cell induction Cocktail (Cat# 004975-93; eBioscience,Carlsbad, CA, USA), for 5 hours, at 37°C, in a 5% CO2incubator.The BD FACSCantoTMFlow Cytometer (BD Biosciences, Beijing,China) was used to detect the differentiation of T-cell subsets.

Hematoxylin-eosin staining

Fourteen days after SCI surgery, the animals were anesthetized with 1.25% tribromoethanol and transcranially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. The spinal cord was harvested and stored overnight, in 4% paraformaldehyde, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose, at 4°C, for at least 48 hours. The spinal cord tissues were prepared into 8-µm-thick optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound-embedded sections, at -20°C.Specimens were successively immersed in 75%, 95%, and 100% ethanol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Images were captured by a microscope (BX43; Olympus, Beijing,China).

Immuno fluorescence staining

Mice were sacri ficed 14 days after SCI and were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde. Spinal cord samples were harvested and dehydrated, using graded sucrose, and then embedded in OCT at -20°C. The samples were cut into 8-µm thick sections, with a freezing microtome (CM 1900; Leica, Wetzlar,Germany), and stored at -80°C. Before immunostaining, the frozen sections were allowed to come to room temperature for 10 minutes and then were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline. After blocking with 5% fetal bovine serum, the sections were incubated with rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein polyclonal antibody (1:500; Cat#ab7260; Abcam), overnight at 4°C. Afterward, the sections were covered with AlexaFluor568-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (ready to use; Cat# ab11011; Abcam) and were incubated for 60 minutes, at room temperature. Subsequently, these sections were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(Cat# ab104139; Abcam). Immunostained sections were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (TCS-SP8; Leica).

Flow cytometric analysis of pro- and anti-in flammatory cytokines

The following fluorochrome-labeled antibodies were used for flow cytometric analysis, according to the manufacturers’protocols: anti-mouse CD4 fluorescein isothiocyanate(FITC, Cat# 11-0041-82; eBioscience), anti-mouse IFN-γ allophycocyanin (APC, Cat# 17-7311-82; eBioscience),anti-mouse IL-17A phycoerythrin (PE, Cat# 12-7177-81;eBioscience), anti-mouse CD25 APC (Cat# 17-0251-82;eBioscience), and anti-mouse FoxP3 PE (Cat# 12-5773-82;eBioscience). Finally, the stained cells were analyzed by a FACSCantoTM flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed using FlowJo V10 software (BD Biosciences).

Cytokine array

The inflammatory cytokine levels in splenocyte-stimulated supernatant were determined, using a customized Mouse Premixed Multi-Analyte Kit (LXSAMSM-10; Luminex, Beijing,China). In accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol, each cytokine was combined with the corresponding antibodyconjugated 5000 beads. Biotinylated detection antibodies were incubated with streptavidin-R-PE. Cytokine levels were measured by a LuminexTM MAGPIXTM. The data were analyzed using Milliplex Analyst 5.1 software (Vigene Tech,Darmstadt, Germany).

Statistical analysis

The results are represented as the mean ± SEM. The data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 5) (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). A one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’spost hoctest, was used to perform pairwise comparisons for normally distributed data. A value ofP< 0.05 was considered signi ficant.

Results

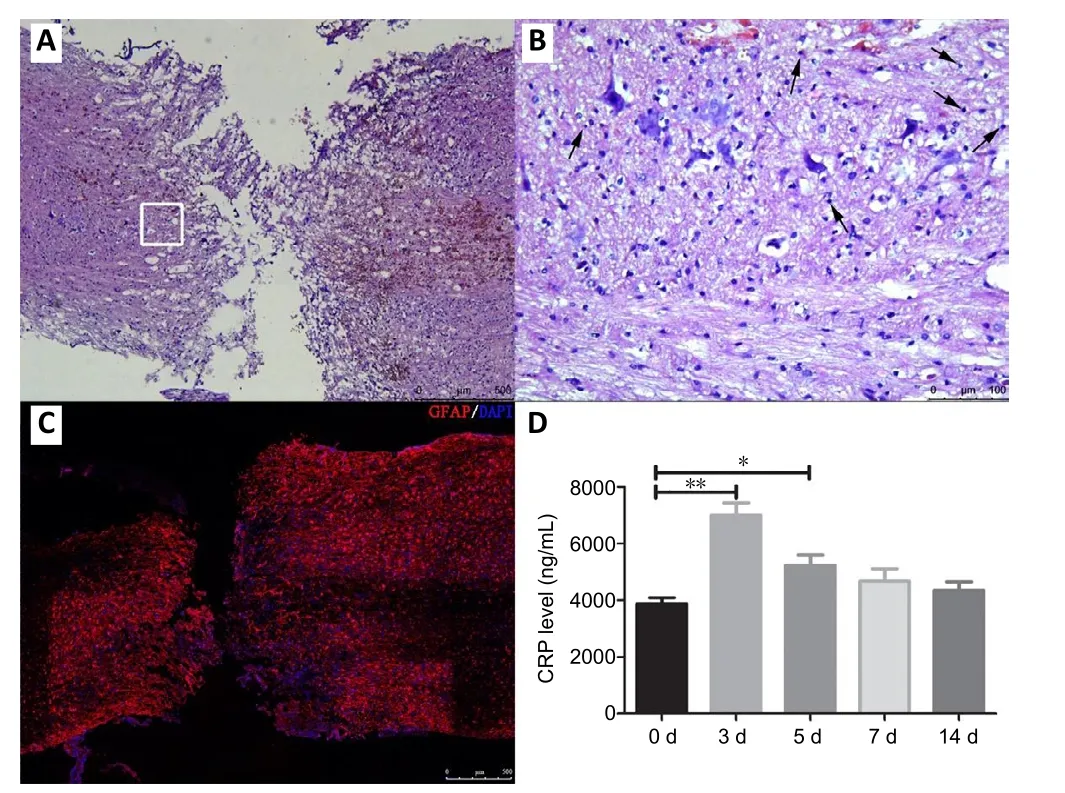

Pathological changes observed in the completely transected spinal cord

After the spinal cord was completely transected at T8, the model mice completely lost sensory and motor functions below the injury level. Hematoxylin-eosin staining was performed, to observe the pathological changes in the injured spinal cord. The normal structure of the spinal cord was lost,and many immune cells in filtrated the injury sites 14 days after SCI (Figure 1AandB). Immuno fluorescence staining for glial fibrillary acidic protein [an astrocyte marker (van Bodegraven et al., 2019)] showed an obvious astrocyte-devoid area in the injured spinal cord (Figure 1C). CRP is an acute-phase protein that participates in the response to inflammation, infection,and tissue damage (Kang et al., 2010). Compared with baseline levels, serum CRP levels were signi ficantly increased 3 days after SCI, before gradually decreasing to basal levels(Figure 1D).

Figure 1|Pathological changes in the transected spinal cord 14 days after surgery.

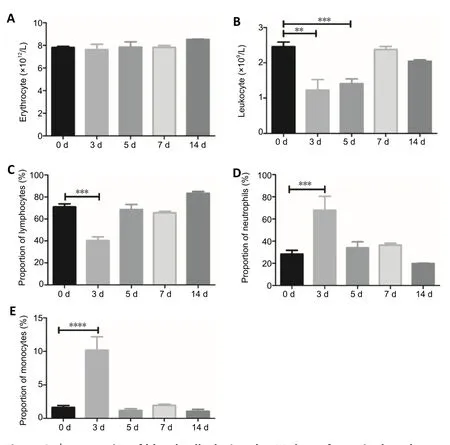

Subpopulations in the peripheral blood after SCI

Leukocytes infiltrate the injured spinal cord after the insult(Beck et al., 2010). Circulating leukocytes were assessed,to analyze dynamic changes in the peripheral blood after SCI. SCI did not affect the concentration of erythrocytes in the peripheral blood at the tested time points (Figure 2A).In contrast, the concentration of leukocytes significantly decreased 3 and 5 days after surgery, and then gradually increased over time (Figure 2B). Further analysis of the leukocyte subpopulations showed that the proportion of lymphocytes in total leukocytes was markedly decreased 3 days after surgery, before gradually returning to the basal level (Figure 2C). In strong contrast, 3 days after surgery,the proportion of neutrophils in total leukocytes increased by approximately three-fold, compared with that in the sham group, and then rapidly decreased from 5 to 14 days,returning to near-basal levels (Figure 2D). The monocyte analysis showed a similar pattern as observed for neutrophils in the SCI model mice. The proportion of monocytes in total leukocytes was significantly increased, 3 days after surgery,and then decreased, 5, 7, and 14 days after surgery (Figure 2E). The numbers of total peripheral blood cells at the indicated time points are presented inAdditional Table 1.

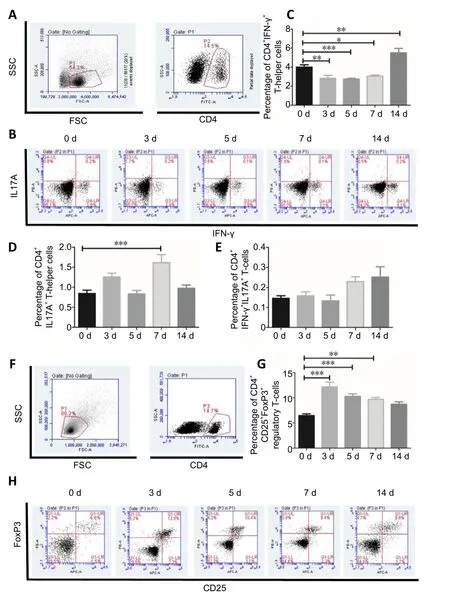

Dynamic changes in T-cell subsets

To evaluate dynamic changes among the CD4+T-cell subsets during the systematic inflammatory response to SCI,splenocytes were isolated from sham and SCI model mice and stimulated,ex vivo, with Cell Stimulation Cocktail, which can induce cell activation, followed by the flow cytometric analysis of CD4+T-cell subsets. Compared with the sham group,SCI mice showed a significant decrease in the proportion of CD4+IFN-γ+T-cells, 3 (P< 0.01), 5 (P< 0.001), and 7 (P<0.05) days after surgery. Notably, 14 days after surgery, the proportion of CD4+IFN-γ+T-cells was higher in the SCI group than that in the sham group (P< 0.01). CD4+IL-17A+T-cells presented a larger population 7 days after surgery in the SCI group compared with the sham group (P< 0.001;Figure 3AD). SCI caused a slight increase in the numbers of CD4+IL-17A+IFN-γ+T-cells at the indicated time points, but these differences were not significant compared with baseline levels (Figure 3E). The present study further analyzed the frequency of Tregs within the population of CD4+cells in the spleen after SCI, using the Treg antibody panel. The flow cytometric analysis showed that the proportions of Tregs were signi ficantly increased in the SCI group compared with those in the sham group, at 3 (P< 0.001), 5 (P< 0.001), and 7(P< 0.01) days after surgery (Figure 3F-H), indicating that SCI induces rapid and dynamic changes in circulating Tregs.

Figure 2| Dynamics of blood cells during the 14 days after spinal cord injury.

Figure 3|T-cell subsets derived from splenocytes using flow cytometric analysis during the 14 days after spinal cord injury.

Expression of in flammatory cytokines in splenocytes

Various inflammatory cytokines secreted into the culture supernatant after spleen cell stimulation were measured at the indicated times after SCI, using a mouse cytokine array. Our results showed that SCI resulted in paradoxical inflammatory cytokine expression. The expression levels of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-17A, and IL-10 remained stable, without any marked changes, at all indicated time points (Additional Figure 1). The expression levels of inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α,IFN-γ, and C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 decreased slightly,3, 5, and 7 days after SCI, and increased signi ficantly, 14 days after SCI, compared with basal levels (Figure 4A,C, andE).In the sham group, the expression levels of inflammatory IL-6 and IL-4 were significantly downregulated 3 days after surgery, compared with the basal levels, but became gradually upregulated and increased beyond the basal expression level,14 days after surgery (Figure 4BandD). The expression level of transforming growth factor-β was inhibited, 3 and 5 days after SCI (P< 0.05), but increased beyond the basal expression level 7 days after SCI (P< 0.05), before returning to nearnormal levels (Figure 4F). Macrophage colony-stimulating factor is an inflammatory mediator, involved in various in flammatory responses and immunity processes (Ushach and Zlotnik, 2016). Compared with the basal level, the expression of macrophage colony-stimulating factor significantly decreased, 3 days after insult, and then gradually increased but never reached the basal expression level, even 14 days after surgery (Figure 4G).

Figure 4|Expression of pro- and anti-in flammatory cytokines in splenocytes within 14 days after SCI.

Discussion

Inflammatory and immune responses are thought to play central roles in the evolving pathological development of SCI(David et al., 2018). Clarifying the dynamic changes that occur during the in flammatory and immune responses will help us to further understand the pathological development of SCI.However, the previous investigations of the systemic immune response triggered by SCI have not yet been sufficiently detailed. In the present study, we surveyed the peripheral inflammatory changes in response to the complete SCI transection in mice, to provide a better understanding of the inflammatory and immune processes that occur after SCI,which may lead to improved SCI immunotherapy in the future.The functional “cross-talk” between the immune system and the CNS is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the autonomic nervous system, which comprises the parasympathetic nervous system and the sympathetic nervous system (Elenkov et al., 2000). The sympathetic nervous system innervates immune tissues and organs, such as the lymphoid and spleen tissues, which respond to neurotransmitters,neuropeptides, and hormones derived from the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system through the activation of specific surface receptors. The peripheral sensory nerves express the receptors for cytokine and chemokines, which can reach the spinal cord and brain by crossing circumventricular organs and/or speci fic transport matter (Schwab et al., 2014), allowing the cytokines and/or chemokines released by leukocytes after immune activation to affect the function of the CNS. If the innervation of the immune system by the sympathetic nervous system is ablated by SCI, normal interactions between the CNS and the immune system become interrupted, resulted in SCI-associated immune depression syndrome. CRP is a common marker of acute in flammation (Kang et al., 2010), and we found that the serum CRP levels were strikingly increased during the acute phase of SCI (3 days post-surgery), before gradually decreasing during the sub-acute phase of SCI, although these levels continued to exceed baseline levels, indicating the presence of a persistent inflammatory response to SCI, during both the acute and sub-acute phases. SCI results in direct “sterile”inflammation and autoimmunity (for example, the CRP response), triggered by self-antigens or pathological damage at the injury site and/or nearby regions of the spinal cord, and indirect systemic immune dysfunctions may be in fluenced by the loss of neuro-immune communications.

Acute SCI has been associated with immune depression syndrome, due to the dysregulation of the hypothalamicpituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system,and has been suggested by some researchers to function as a means for preventing or confining damage. However,simultaneously, systemic SCI-associated immune depression syndrome may disrupt the efficiency of protective immunity(Jones, 2014). Interestingly, we found that systemic immunosuppression was transient during the acute phase of SCI, whereas most dysregulated indicators of immunization and inflammatory responses were progressively restored to near baseline levels during the sub-acute phase. These results differ from the post-SCI immune dysregulation reported in previous studies, which lasted from the acute to chronic phases (Cruse et al., 1993, 1996; Lucin et al., 2007, 2009;Zhang et al., 2013). The temporal changes in the mobilization of systemic immunity after SCI emphasizes the complex and paradoxical patterns of immune and in flammatory responses after SCI. For example, the dynamic changes observed in lymphocytes contrasted with the changes observed for neutrophils and monocytes among the total leukocyte population after SCI. The evolving state of CD4+IFN-γ+T-helper cells and CD4+IL17A+T-helper cells demonstrated a completely different pattern from that observed for CD4+CD25+FOXP3+Tregs in the spleen. The generic therapies aimed at immune suppression are largely unsuccessful because of the temporal evolution in immunity and in flammation that occurs after SCI and their changing functions over time (Schwab et al., 2014).Additionally, most studies examining neuro-immunity after SCI have focused on the “compartmentalized” intraspinal inflammation and immunity, and the associated cellular and molecular mechanisms that occur in the spinal cord,but neglecting to examine time-based changes in systemic in flammation.

The SCI-elicited inflammatory response is a double-edged sword, exerting both detrimental and bene ficial effects, overtime, for the recovery of SCI. The spinal cord healing process is multifactorial, and the peripheral immune response is vital to the maintenance of spinal cord homeostasis (Rust and Kaiser, 2017). The local immune response to SCI affects the systemic immune response, which in turn in fluences the pathophysiological changes that occur in the injured area and the repair process. Systemic immune dysfunction represents a component of the “SCI disease” continuum and likely directly or indirectly affects the “immune-specialized” milieu of the spinal cord. Thus, additional studies remain necessary to further investigate the occurrence and development of systemic immunity and in flammation, the interplay between systemic and intraspinal inflammation and immunity, and the crosstalk between immunity and neuronal regeneration.A strong understanding of the systemic immune alterations that are driven by CNS injuries, such as SCI, cerebral stroke,and traumatic brain injury, are necessary for the development of effective drugs designed to reverse dysregulated immune responses and functions, by targeting key immune checkpoints, to achieve structural and functional repair in CNS-injured patients.

In short, we surveyed systemic immune alterations overtime, after SCI, and found that SCI resulted in acute systemic immune dysregulation, affecting CRP levels, circulating leukocyte concentrations, the CD4+T-cell subsets derived from splenocytes, and inflammatory cytokine expression;however, this systemic immune dysregulation was transiently and progressively restored during the sub-acute phase of SCI. Our study deciphered an integral spectrum of systemic immune responses that are initiated by SCI and provided a further understanding of the crosstalk between the nervous and immune systems, as well as systemic and intraspinal in flammation and immunity.

Author contributions:Study concept and design: BW; in vivo experiments: TYG, FFH, YYX, WQW, and LDW; statistical analysis: DM, and YC; manuscript writing: TYG; manuscript revision: TYG and BW. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Con flicts of interest:The authors declare that they have no con flict of interests.

Financial support:This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, Nos. 81571213 (to BW), 81800583 (to YYX),81601539 (to DM), and 81601084 (to YC); the National Key Research and Development Program of China, No. 2017YFA0104304 (to BW);the Nanjing Medical Science and Technique Development Foundation of China, Nos. QRX17006 (to BW), QRX17057 (to DM); the Key Project Supported by Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation,Nanjing Department of Health and the Nanjing Medical Science of China,No. 201803024 (to TYG) and Innovation Platform, No. ZDX16005 (to BW).The funders had no roles in the study design, conduction of experiment,data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Institutional review board statement:The study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Experimental Animal Center of Drum Tower Hospital, China (approval No. 2019AE01040) on June 25, 2019.

Copyright license agreement:The Copyright License Agreement has been signed by all authors before publication.

Data sharing statement:Datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Plagiarism check:Checked twice by iThenticate.

Peer review:Externally peer reviewed.

Open access statement:This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak,and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Open peer reviewer:Siddharth Krishnan, The University of Manchester Faculty of Biology Medicine and Health, UK.

Additional files:

Additional Table 1:The cell number of peripheral blood cells.

Additional Figure 1:In flammatory cytokines without expression change in splenocytes.

Additional file 1:Open peer review report 1.

杂志排行

中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Gut microbiota: a potential therapeutic target for Parkinson’s disease

- Stem cell heterogeneity and regenerative competence: the enormous potential of rare cells

- Therapeutic potential of neuromodulation for demyelinating diseases

- Glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibitor SB216763 promotes DNA repair in ischemic retinal neurons

- Brain plasticity after peripheral nerve injury treatment with massage therapy based on resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging

- Effectiveness of oral motor respiratory exercise and vocal intonation therapy on respiratory function and vocal quality in patients with spinal cord injury: a randomized controlled trial