非正规框架规划设计方法

2021-08-24戴维加弗努尔张晨笛

著:(美)戴维·加弗努尔 译:张晨笛

1 对非正规城市的偏见

为什么对于显著的非正规城市问题的处理如此低效?目前有近10亿人生活在自建区,未来30年,此人数将会再增加10亿[1]①(图1)。然而,政治家、学者和专业人士对非正规城市往往存在偏见,妨碍人们欣赏非正规城市的积极方面,并进一步阻碍他们实现更好城市标准的愿望。

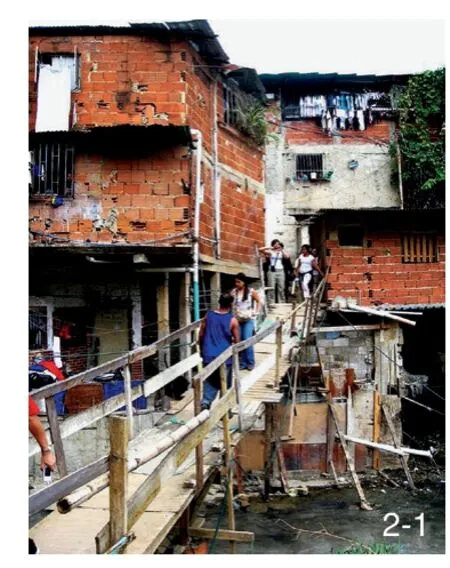

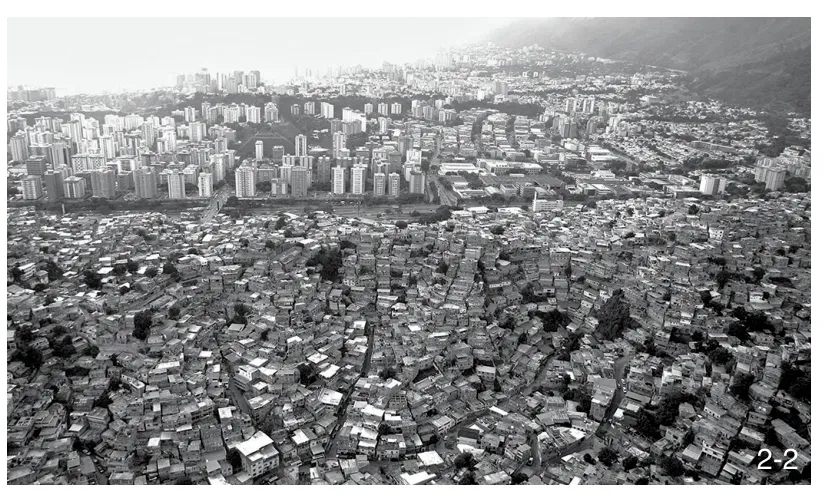

1 靠近中央商业区的非正规住区(委内瑞拉加拉加斯)Informal settlements adjacent to central business areas(Caracas, Venezuela)

在文化价值观和经济上,较富裕和在政治上占主导地位的人往往与住在城市里的穷人不同。政治家、专业人士和中上层阶级的消极态度源于对非正规社区出现的原因缺乏了解。正规城市的居民往往认为非正规住区的居民是外来的,对他们的生活水平有负面影响,但在许多情况下,他们甚至没有去过非正规住区。

笔者的祖国委内瑞拉在经历了不太成功的社会主义革命之后,经济萧条,对非正规城市的研究具有一定代表性。虽然其政治目标是为不太富裕的人口服务,但政府官员和普通民众都经常提到:“巩固社区就是巩固苦难。”或者:“我们必须提供体面的住房来替代这些不适合居住的地方。”在笔者看来,这两种说法都反映了对非正规城市化动态的误解。并且非正规住区一直被忽视,只有一小部分新增住房需求会涵盖在(政府组织的正规)社会住房计划中。

尽管各大洲有许多例子表明改善现有非正规住区的生活条件是可行的,但仍有一些国家,特别是那些具有高度中央集权的政府形式的国家,在这种情况下,拆迁和摧毁自建的非正规住区仍然是常态。以津巴布韦为例,在2008年,容纳近80万人的大型非正规住区被夷为平地。大多数情况下,没有为流离失所的居住者提供其他选择[2]。因此,这些移民最终部分在邻国南非定居,部分则返回其原籍的农村地区,或重新开始在其他地区进行非正规居住。这种性质的强制行动可能可以将原居住者的居住场地用于其他用途;但对那些曾居住在此地的人来说,这是暴力破坏,导致他们只能在其他地方居住,由于未来面临被驱逐的风险,他们对社会的怨恨和不安全感增加。在更富裕的发展中国家,比如中国,城市更新进程非常普遍。而这些项目却扰乱了非正规和传统的城市区域(中国的城中村),迫使居民远离原居住地,他们必须适应与之前完全不同的居住条件,如高层住宅区。在这个过程中,这些项目侵蚀了当地的生活方式和生活传统。这些对非正规住区居民的驱逐还与可耕农业土地的减少、自然栖息地的减少,以及尊重自然、规避自然灾害的文化习俗的丧失有关。

2 非正规都市主义的优缺点

许多穷人除了自建住所和社区别无选择。他们无法参与正规的房地产市场(的各项买卖活动),也负担不起正规住房的相关成本,即使这些正规住房项目得到了高额补贴。从农村或小城镇进入城市或试图从大城市现有的非正规区域迁移到城市的移民,没有稳定的工作、固定的收入或储蓄。他们无法获得抵押贷款或其他形式的补贴以购买住房或租房。因此,对于那些不太富裕的人来说,唯一的选择是非法占有大量未开发的土地,或者以他们能负担得起的价格从非法或非正规开发商那里购买土地。乡村庇护所逐渐转变成一个更稳定的住所。它们通常不只是住所,更像活的有机体,能够发展为大家庭、出租单位或一些诸如小型商店及制造业的生产活动场所。

在大多数情况下,非正规住区的居民不去支付水电等公用事业费用,也不支付财产税,同样也无法申请到商业执照。在整合的后期阶段,学校或日托中心等基本公共服务由城市或非政府组织提供。在自建社区中,社会联系也非常紧密,场所感和身份感通常比任何规划中的社会住房项目都要强烈得多。所有这些因素都给非正规居住者带来了巨大的好处。虽然非正规住区的形成与产生原因对于其中的居民们提供了许多好处,但非正规住区并不是全无问题。在发展中国家的自建城市里,社会债务在不断累积和升级。由于缺乏获得信息、教育、保健服务的机会,或者不知道如何更好地利用商业网络,许多非正规住区的居住者相对于正规城市居民而言,常处于不利地位[3-4]②。虽然有许多富有创造性的案例可以说明企业是如何在非正规场所中繁荣起来的,但这不是常态。

不同国家、城市或地区的情况可能有很大差异,但(非正规)住区往往缺乏公共部门直接或间接提供的基本城市条件(图2-1、2-2)。这些不足体现在以下方面。

2-1 洪涝区域上的非正规住区(委内瑞拉加拉加斯卡塔驰)Informal settlements on a flood plain (Catuche, Caracas,Venezuela)

2-2 陡峭地形上的非正规住区(委内瑞拉加拉加斯)Informal settlements on a steep terrain (Caracas,Venezuela)

1)处于不安全的地点,如洪泛区、陡坡、棕地和地质不稳定的场地。这些地点常常无法保证人身生命安全,易造成财产损失并造成环境破坏,如森林砍伐、流域破坏、土壤侵蚀、含水层污染、生物多样性减弱等。

2)缺乏基础设施,特别是饮用水和下水道,造成公共卫生问题。

3)社区服务差,例如在教育、医疗援助、体育设施、娱乐设施等方面。

4)非正规区域内的公共交通系统不完善,可达性、流动性和连通性弱,以及在这些方面与正规城市区域也比较割裂。这些因素造成了空间隔离,使居住者难以在正规城市获得工作和服务,也无法在居住地获得基本的城市服务,如警察监护、紧急救护、消防、垃圾收集等。

5)街道或人行道狭窄,以及缺少甚至没有公共场所,减少了社交和休闲的可能性。

6)社会怨恨的增加以及上述情况的发生常会导致暴力、不安全和犯罪,在许多国家,非正规和正规地区的居民都认为这些指标是最令人关切的,是城市发展水平低的标志。

一定要记住的是,当住区不断扩大变得更密集且远离旧的非正规区域和正规城市时,城市问题往往会被放大。为了减少正规城市和非正规城市之间的差距,缓解不断升级的、紧张的社会局势,迫切需要一套新的规划、设计和管理模式。

3 应对非正规城市扩张的尝试

在大多数发展中国家,现代化和工业化带来了显著的人口变化。为了寻求更好的收入和服务,农村人口大量迁移到城市。在某些情况下,这样的迁移源自武装冲突、伦理问题、宗教问题、暴力或饥荒。

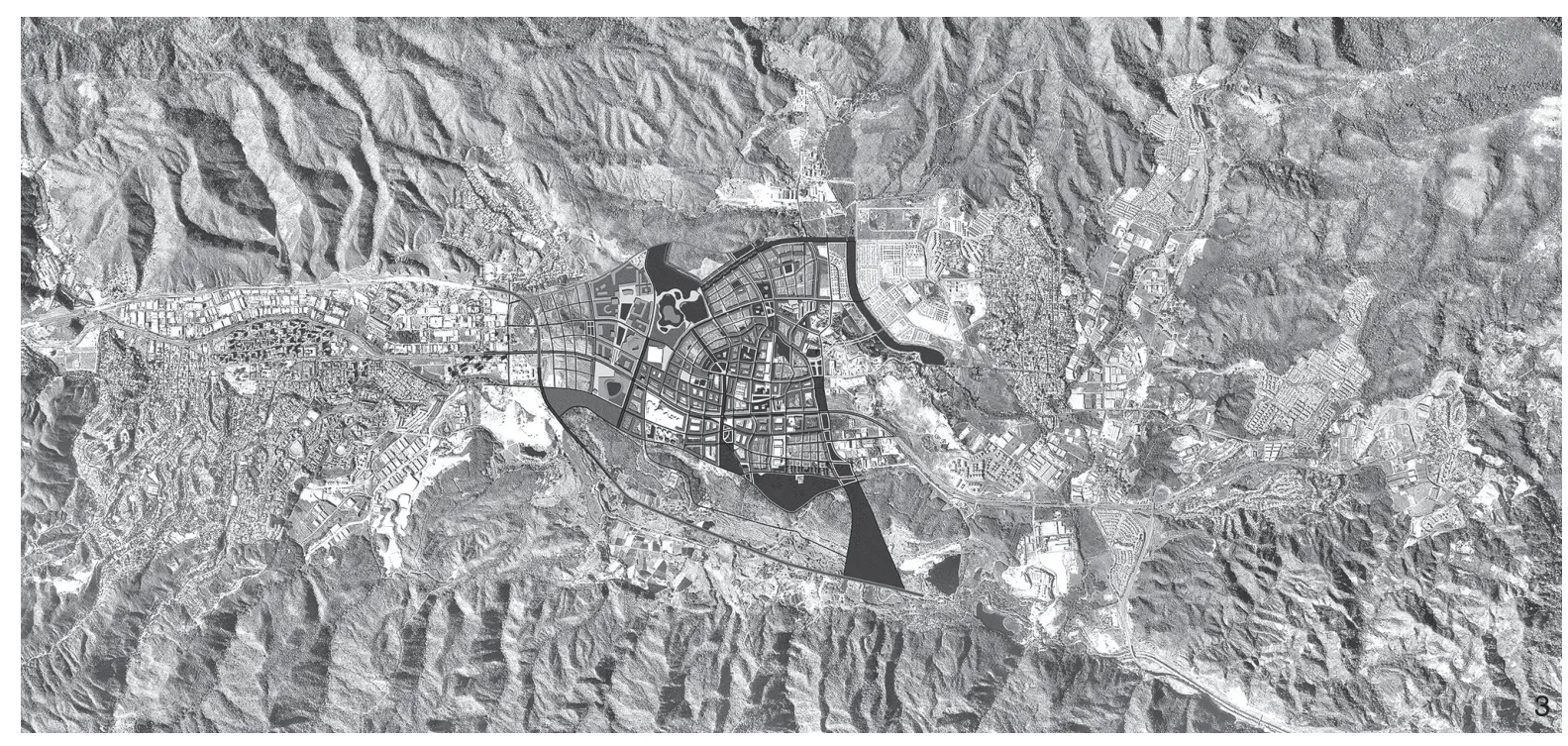

政府对非正规住区的第一反应往往是忽视他们,或让他们远离“称心如意的地点”(图3)。随着时间的推移,当局意识到无法阻止非正规城市化的进程。为应对此现象,他们试图为城市发展提前规划;推进社会住房计划、“场地和服务项目”或发展改善住区的项目。正如将要阐释的,这些方法在不同程度上取得了成功,但因为人口的快速增长、自建地区的规模以及发展中城市的复杂性,其也有局限性。下面的内容阐述了这些尝试性解决方案的一些缺陷。

3 游离于城市设计所规划的范围之外的非正规住区(委内瑞拉法哈多城)Informal settlements outside the boundaries of an official Urban Design Plan (Ciudad Fajardo, Venezuela)

3.1 传统城市规划带来的不良影响

在大多数发展中国家,公共机构主要负责制定规划指导城市发展。这些规划政策与20世纪下半叶以来工业化国家创造制定和应用的政策没有太大区别。这些规划主要着眼于人口预测,设想城市应该如何扩张,在哪里扩张。他们建议了一定的建筑密度与用地范围,这些建筑和用地与提供基础设施和移动系统以及服务相关。这些政策通常是一般性的工具,没有考虑到发展中国家的背景和文化条件。它们也不涉及非正规形式的发展增长。最好的情况是,他们只是在地图上标注并在法律上承认非正规住区的存在,但不会为其规划新的住区。

此外,这些规划可能会对非正规区域的发展选址和发展方式产生不良影响。大多数发展中国家继承了殖民时期不公平的土地所有权模式所留下来的遗产,财产集中在少数人手中。因此,公共土地有限,甚至在某些情况下是紧缺的,这就需要控制较贫穷阶层住区的人口增长。这些规划政策一出台,就会把农村土地变成城市土地,促进并刺激房地产市场。

随后政府会提供基础设施,如道路、饮用水和下水道,在私人土地上创造额外价值,通常并没有提供增加这些有价值的设施以帮助数不胜数的(非正规)庇护所的机制。正如前面所提到的,较贫穷的人口无法进入正规的房地产市场,他们被迫居住在不太理想且服务设施条件差的场地,而这些场地通常是在规划政策所划定的城市边界之外。

3.2 社会住房无法满足需求并可能导致城市问题

社会住房计划通常旨在重新为现有的非正规住区选址、迁址,或应对新移民潮。特别是在非正规城市化的早期阶段,当局仍然相信可以彻底消除非正规住区或避免它们的增长。此外,社会住房计划迫使居住者适应不同的生活条件,抛弃他们自身的文化/乡村习俗。同时,非正规住房所提供的灵活性优势也被削弱了。

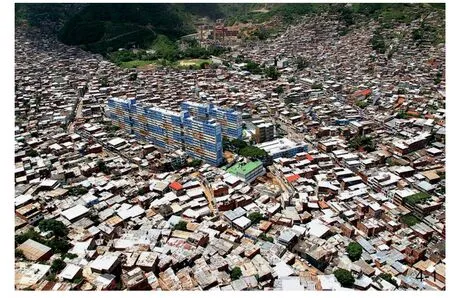

公共住房政策通常关注的是可提供的住房单元的数量,但这样的城市条件不一定能让这些住房成为可持续的栖息场所。为了寻求便宜的土地,公共机构或被政府协助的(负责兴建一些适合非正规住区居民的)开发商在远离就业、服务和交通的城市边缘地区进行开发建设。因此,这些项目加速了城市扩张并导致社会孤立化。即使在能够提供大量补贴住房的较富裕的发展中国家,自行建造住房的移民人数也逐渐超过在公共或公共与私人混合型住宅开发项目中定居的移民人数。社会住房并没有为那些负担不起的人提供可行的解决方案。

4 改善非正规住区的成功规划或有局限性

学术界、公共部门和各种机构逐渐认识到很大一部分人口住在自建地区。他们知道这种情况会持续下去,因此开始承认需要关注非正规住区。但当地专业人员经常缺少处理非正规问题的培训和专业实践知识。

然而,许多发展中国家对非正规住区的看法已经改变。随着非正规住区的居民比例增加,他们的政治影响力也越来越大。因此,许多国家,如委内瑞拉、巴西、哥伦比亚,已改变其管理领土和城市规划的法律框架,承认非正规居住,并就如何改善现有的非正规区域提供规范和标准。最初,实施简单的城市干预措施,如在陡峭处的居民点铺设道路和小径与楼梯,安装公用设施或下水道,建造学校和基础医疗设施(图4-1、4-2)。官员们还授予他们土地所有权。虽然这些举措受到居住者的欢迎,但在显著改变社区的生活条件方面,还是显得微不足道。因此,非正规区域相对于正规城市仍处于不利地位。

4-1 20世纪50年代建造的住宅区被非正规增长所吞没(委内瑞拉加拉加斯)Housing blocks built in the 1950’s, engulfed by informal growth (Caracas, Venezuela)

4-2 哥伦比亚麦德林圣哈维尔的公共空间和地铁电缆Public spaces and metro-cable in San Javier, Medellín,Colombia

20世纪90年代,笔者曾任委内瑞拉城市发展国家主任。在此期间,支持了一批有才华的研究人员,包括拖林达·宝利瓦、约瑟芬·鲍多和弗雷德里克·比利亚。这些研究人员首次提醒了对非正规(住区)采取措施的急迫性。笔者通过公职协助改善加拉加斯非正规住区的计划,这项计划也反映了他们的调查结果[5-6]③。在不到一年的时间里,这个团队研究成果颇丰。几年后,当乌戈·查韦斯就任总统后,鲍多教授被任命为委内瑞拉住房委员会的会长,他将改善非正规住区的计划列为国家优先事项,并组织了数百场竞赛,逐步开始实施这些计划。然而,有影响力的军事部门仍然对以非正规住区为重点的倡议抱有一贯偏见。此外,自上而下的政府组织限制了这些行动。

尽管有一些缺点,在过去10年间委内瑞拉(在非正规住区方面)取得的先进实践经验,对其他国家有着指导作用。有价值的信息、工作方法和设计标准正在被分享并应用于各种环境,在南美的一些国家和南非,特别是巴西、哥伦比亚、玻利维亚和其他安第斯国家,都有被视作整体康复项目的重要提议[7-9]④。

也许最著名的例子是在哥伦比亚的麦德林市进行的举世闻名并多次获奖的提升改造项目。就在30年前,麦德林还被列为世界上最暴力的城市。统计数据显示,最高比例的暴力犯罪集中在几乎人迹罕至的山顶的非正规区域[10]⑤。2014年4月,上海举办了世界城市论坛。来自世界各地的参会人员能够欣赏到应对城市变化的管控手段的创造性设计、透明度,以及了解改善最贫困地区之一的生活条件的方式。麦德林获得了比大多数发展中国家更多的市政资金和技术支持。然而,以下是促成麦德林成功的主要因素。

1)从政治上承诺解决积累了数10年且被暴力加剧的社会债务。

2)当局将非正规住区提升项目作为主要行动目标,并将其作为更广泛的城市战略的一部分。

3)社区参与项目规划、设计、建造、运营和维护的各个阶段。

4)组织高效、高知、诚信的团队,提供高质量的设计解决方案,并对项目持续管理。

尽管麦德林提升改造项目取得了令人满意的结果,但在试图将非正规城市与正规城市的生活条件相匹配时,所取得的成就也是有限的。对高度固化的住所采取行动是一个艰难的过程。要引入开放空间、改善连通性、提供基础设施和公共服务,或者从高风险地区重新安置移民,就需要替代住房。搬迁需要复杂的谈判技巧。在同一社区或相邻地区,很难找到拆迁后适宜的安置房用地。此外,那些需要搬迁的居民必须愿意搬迁。

在社区尺度,对现有住区的城市提升似乎实施得很好,但由于空间限制使得解决更大的城市/大都市需求的措施难以实施。例如,很难在高度固化和密集的居民点内提供服务、基础设施和公共空间,如大型公园、技术学校、大学、食品配送和运输中心、医院、大型体育设施、制造业和工业区等。最好的非正规住区重建计划也很难处理尺度更大以及设计城市需求方面的问题,而这已成为世界范围内的常态。

还必须提到的是,尽管当局明确承认非正规都市主义是无法阻止的,但是支持发展新的非正规区域的阻力仍然很大。甚至在法律制度层面和普遍做法明显有利于改善现有非正规住区的区域,或是已经成功地实施了这些措施的区域,发展新的非正规区域的阻力还是很大④。

下文将重点讨论如何以预防性和可持续的方式应对以非正规(住区)为主的城市的扩张,并简述场地和服务项目——非正规框架(IA)规划设计方法的第一步。笔者主张用IA作为应对非正规性以及平衡(正规的)城市增长的当代挑战的替代方法。

5 场地与服务:自建房屋理念构架

早在20世纪60年代,一群关心社会的学者、研究人员和专业人士就清楚地认识到,传统的城市规划和社会住房计划无法满足不富裕人群日益增长的住房需求。这一群体包括在城市规划和设计研究中经常被提及的作家和设计师,如霍雷肖·卡米诺斯、约翰·特纳、彼得·兰德和赫尔曼·桑佩尔等。他们提出了“场地与服务”这一理念,简言之:居住者知道如何占领大量土地,并逐步建造、扩建和升级住所;却无法获得通常需要公共部门、专业人员、机构或社区组织支持的城市条件。因此,这个理念的目标是提供一个平衡的栖息场所,其中包括可达性、多分区城市布局、基础设施以及逐步融合社区服务与设施的开放空间。

这些发起人将该理念传递给成千上万的学生,这些学生随后成为活跃的专业人士,在全球领先的学术、金融和规划机构担任重要职务。根据不同场地的资金与管理条件,场地和服务计划的应用范围有所不同。在某些情况下,它提供基本的毛坯房或带有浴室和厨房的居住单元,同时提供规划和技术援助,以指导住区的扩大和改善过程。在其他情况下,他们设想通过提供技术和资金支持,协助社区在当地生产低成本的建筑材料,以提供用户友好的建造方式。

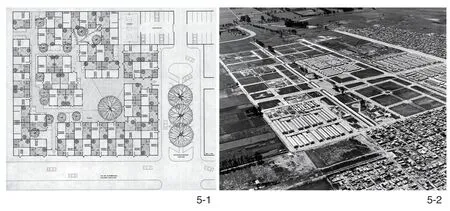

也许这些倡议中最具象征意义的是1965年的普雷维(PREVI)竞赛(图5-1、5-2),该竞赛是为秘鲁利马南部大片空地的城市化而组织的。彼得·兰德教授统筹PREVI竞赛,他呼吁来自不同区域的杰出规划师和设计师参与其中。兰德教授的推动及当时秘鲁总统、建筑师费尔南多·贝朗德·特里的支持,促进了该项目的实施。在普雷维,很多社区的设计方案是根据竞赛的获胜方案制定的,更大的城市框架将不同的社区设计方案联结在一起。

5-1 秘鲁利马普雷维竞赛——场地和服务的入围设计,由赫尔曼·桑佩尔设计Entry for the Site and Services PREVI competition, Lima, Perú, by Germán Samper5-2 毗邻非正规住区的社会住房城市框架。哥伦比亚波哥大Metrovivienda项目,由康拉德·布鲁纳,古斯塔沃·佩列,爱多华多·桑佩尔和西门娜·桑佩尔设计Urban framework for social housing adjacent to informal settlements.Metrovivienda project, Bogotá, Colombia. Project: by Konrad Bruner, Gustavo Perry, Eduardo Samper and Ximena Samper

几年前,笔者访问了普雷维,在项目设想提出的45年后,最终得以看到住宅和公共空间的成果。然而,普雷维只是一个非常大的领土上的一个小的场地,其中有250多万人居住在非正规住区。对于普雷维的大多数居民来说,基本的城市服务、设施和工作都在正规的城市中。他们仍需超过1.5 h通行穿过一系列低于标准的非正规区域。

从2008年开始,笔者多次到访麦德林,见证过正在进行的、多层次的变革进程。这些进程从根本上改善了当地的非正规社区。这项提议是在市长塞尔吉奥·法哈多的领导和亚历杭德罗·埃切维里的专业协调下提出的。这些地区在下一届政府的执政领导下继续繁荣发展。笔者还带着学生去了麦德林,花了几个学期的时间来制定提案,设想了自建新区的可持续发展计划。这些设计研究项目的目的是在规模和效果上超越目前的场地和服务项目。

利马和麦德林的做法有着鲜明对比。在利马,在先导性城市规划框架指导下的区域/社区现已被未经规划的非正规区域吸纳。在麦德林,这些项目可以被认为是在现有的非正规住区进行操作的一种纠正性的“城市手术”,这些住区是更广泛的城市战略的一部分。正如前面提到的,这些不同的举措为笔者在摘要中提到的著作提供了关键的视角④。在这项工作中笔者引入了非正规框架(IA)规划设计方法(图6)。

6 非正规框架(IA)手稿(戴维·加弗努尔)Sketch of an Informal Armature by David Gouverneur

6 非正规框架规划设计方法

自从20世纪60年代场地和服务项目出现以来,并未对自建住区的发展进行提前思考和行动,迫切需要新的模式来促进新的非正规城市的增长。我们需要实施各种方法,利用能够挖掘非正规性潜力的工具,并与自建栖息场所的社区进行接触。应该记住,在许多情况下,我们是在非常大和复杂的城市地区试点,应该借鉴创新的设计和具有效用的思想。规划设计的目标应该是引导以非正规为主的城市提升城市效能,并帮助居民获得更好的生活条件。

IA与以前的方法有何不同?IA在原则、设计思路和适用性方面力求简单。它的目标是获得令人信服的结果。它表明了正规和非正规城市建设模式之间存在共生关系,这可以产生丰富和动态的城市生态系统,具有高度的竞争力和弹性④。IA方法的关键条件如下:1)把握先机和积极变革;2)实体性和效用;3)融合措施与多尺度措施;4)环境友好;5)简单易行。这些条件都是密切相关的。IA利用灵活的设计组件来适应不同的场地条件。

6.1 把握先机与积极变革

IA本质上是一种把握先机的规划和设计方法,旨在促进以非正规城市为主的增长。作为一个支持系统,它旨在增强非正规城市化的内在动力,主要前提——提前规划和引导城市化进程,使发展更加平衡和高效。这与非正规社区的改造形成了对比。为使IA有效可行,必须符合下列条件:1)政治上接受未经政府协助的非正规性住区自行发生,接受其在没有遵循基本城市框架的情况下,占据非正规规划所圈定的场地,认识到非正规住区将导致复杂的城市情况并会产生严重的社会和环境影响;2)公共部门具有重组、收购的意愿和能力或与私营部门合作发展的意愿和能力;3)机构里团队的倡导者要忠实致力于IA提议。团队还必须能够使内部评审标准适应当地实际情况,让社区参与进来,根据特殊需求学习专业知识,并促进IA示范地的转型,直到被协助的对象不再需要协助为止。

6.2 实体性与效用

大多数发展中国家的传统规划都变成了没有考虑设计的静态土地利用规划;它们主要集中在对房地产市场的控制上,不涉及非正规城市化。发展中国家经常将遇到的问题和无力解决这些问题的原因归咎于缺乏财政来源。虽然这些国家确实可能存在经济上的限制,但更大的问题源于缺少对于确定事务优先级、协调行动和确保效率与透明度的一致愿景。麦德林的案例指出了引入先进的规划和设计标准、高效和持续的管理,以及与社区携手合作的重要性,这是确保改革措施交付和问责的最佳方式。

因此,IA规划设计方法将空间组织和设计标准的概念与现场管理相结合。其重点在于如何通过预设简单的空间组织模式,以及用这些简单的空间组织模式来吸引并引导非正规住区的居民在住区形成初期对场地进行占领,并建立牢固的联系。该方法的作用很大程度上依赖于在项目的倡导者和社区之间建立信任,以及管理城市变化的方式。IA引发的变革不仅会发生在公共区域,而且在适当的时候也会出现在自建地区作为补充,随着社区的整合与发展,非正规住区有着更宏大的远景并成为更大的城市群的一部分。

从场地和服务项目以及非正规住区改善计划中获得的主要经验之一:自建城市的空间组织和实体性非常重要。可持续的城市建设需要高质量的规划和设计。这可能包括:设计引人注目的、具有效用的城市景观,促进创业,减少能源的合成和浪费,加强社会互动,减少暴力,支持共享参与式治理等。IA倡导者应该努力让早期居住者感到他们是改善其所处地区的积极组成部分,并帮助他们参与住区建造和发展的各个方面。

6.3 融合措施与多尺度措施

无论是场地和服务项目,还是非正规住区改善项目,都在试图将自建的动力与规划和设计相结合。发展中国家的运作也遵循同样的逻辑,但其目标是实现高度平衡和有竞争力的城市,这迟早会成为主流,因为许多发展中国家城市化的主要形式将是非正规住区。因此,IA倡议者必须使用专业技能设计规划早期阶段的居住选址,按照新移民的基本需求部署足够简单的设计组件,同时计划解决城市以及特大型城市里的更大城市集合体。这并不容易,且需要熟练的“领航员”。

各种类型的城市规划框架及技术都可以追踪记录自建住宅土地。正如场地和服务项目所设想的那样,包括其他形式的社会住房——这些是被IA改造的地区非常重要但非唯一的组成部分。IA考虑的是几段或几块可能最初包含简单的交通系统或可以安装接待帐篷和临时供应饮用水的闲置土地。这些开放空间最终可以帮助高效的公共交通系统可持续运行,保持使用的多样性,使得城市设施以及引人注目的公共空间可持续。IA还可以预先确定如何保护水道和种植区,这些区域将成为城市的休闲廊道,IA也可以将场地初步设想为回收中心,这样回收中心提供建筑材料以帮助居住者建造他们的住所。这些地区最初可以用来启动都市农业项目,最终会让位于制造业中心、技术学校和大的城市市场等。

在社区愿景得以实现以及收入水平得到提高之前,一些有临时用途的土地可能会一直保留在公众手中。私营部门可以提供更先进的商业区和便利设施。这些行动可以为IA协助机构提供机会,吸引私人投资,为高收入人士提供综合用途的建筑或住宅,提供原住民所需的正规住宅、办公室、电影院和康乐设施。通过这些行动所获得的额外价值,可帮助IA倡导者赚取收入用于再投资于同一地区的其他服务,或在新城边界重新推行类似的IA措施。IA管理的这些区域将随着自建的活力和特点与正规城市的便利设施相结合而蓬勃发展,成为一个真正的融合体。

6.4 环境友好

具有环境适应性的当代城市化规划设计有义务解决环境问题,这些问题不仅对社区的福祉至关重要,而且对地球的健康也至关重要。在许多发展中国家,传统的城市规划仍然决定着正规城市的风貌,但在常规城市规划议程中并未考虑生态环境因素,而在场地和服务项目中也未将其视为IA规划设计方法实施的前提。

由于在非正规居住发生前就开始实施IA规划设计方法,因此可以决定定居点最初的物理和表现形式,可以提供一个有利且灵活的环境来实行环保标准。一些能想到的最敏感的方面包括:邻近的流域、生物多样性地区、宝贵的农业土壤、毗邻和在城市地区内的水文网络的保护机制。同样,IA可以促进绿色基础设施、步行和清洁公共交通网络、环保回收项目、社区农业花园等的引进。积极的IA倡导者的存在,将使规划、设计和管理新的非正规/正规地区的思想融入早期定居者的日常生活。重要的是要记住那些未被帮扶的非正规住区的居民,特别是他们刚入住仍忙于考虑生存问题时,他们不可能意识到或关心环境问题。他们中的许多人来自农村地区,在成为城市居民后,对自然变得陌生并丧失农业技能。IA帮助新的城市环境更好地容纳这些农业或自然的文化实践。

6.5 简单易行:基于灵活的设计组件,适应不同的场地条件

纵观历史,城市一直在尝试新的城市组织模式。有些是由受文化实践影响的设计原型塑造的,而另一些则是由领导者、设计师、经济利益集团、服务提供者等引入的。设计解决方案经常被复制到与它们产生的条件不同的环境中。那些流行的解决方案在空间层面实施上和执行方式上都比较简单。在发展中国家使用的一般规划和设计原型符合特定的意识形态和政治、经济和社会目标,但并不总是有利于大多数人。IA提出了一套简单的设计组件,其主要目标是为发展中国家中人口占比最大的穷人提供更好的生活条件。这些组件在性质、规模或形态和效用上都不是固定死板的。相反,它们嵌入了能够支持前面提到的多个流程的原则。这些空间形态解决方案以及表征式解决方案的成功布局,将取决于当地的环境和文化差异,以及IA倡导者让社区和其他城市参与者参与行动的能力。

为了简化应用程序,IA将设计组件分为以下几类:廊道、板块和保育者。这些组件旨在作为城市组织剂,促进被割裂的杂乱无序的城市融合成一个综合的系统,支持非正规(住区的进程)并发挥不同的作用。

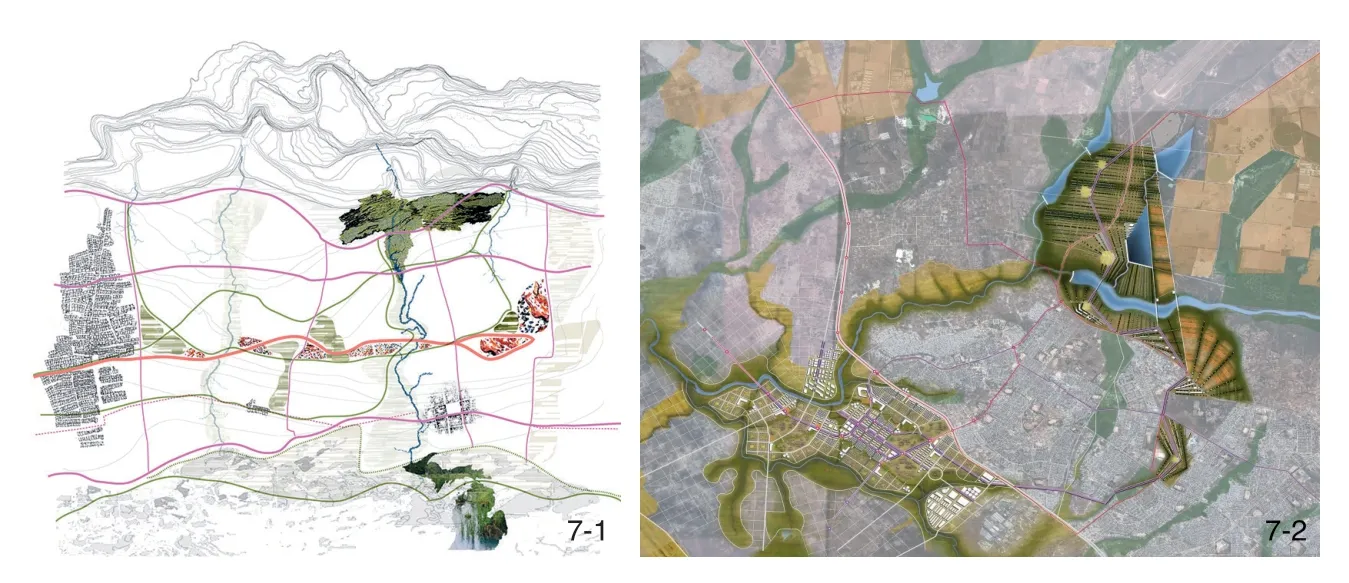

廊道本质上是构成公共区域的线性元素组件或者条带,是开放空间、基础设施、交通系统、水管理设备以及服务等的骨架或者基因。廊道又分为两类。1)吸引点:作为吸引聚集点或热点,鼓励人口和活动向更适宜的地区集中,提供空间和管理条件以更好地处理它们;2)保护点:与吸引点相反,消耗城市能量,协助保护环境,并作为缓冲,以避免非正规和正规形式的城市在敏感区域的占领/扩张。吸引点和保护点将作用于更大城市范围里更高比例的住区变革,并需要更多的公众参与来实现其目标,特别是在占领、巩固和增长的早期阶段(图7-1、7-2)。

7-1 廊道(吸引点和保护点)综合分析图Composite diagram of Corridors (Attractors and Protectors)7-2 城市尺度廊道设计(津巴布韦哈拉雷市奇通维扎)Protector Corridors proposed for Chitungwiza, Harare, Zimbabwe

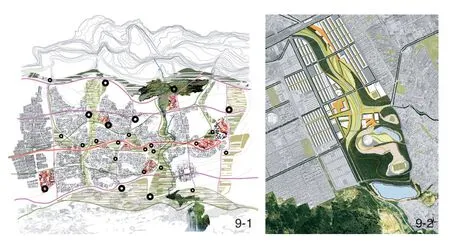

板块:代表由廊道滋养培育而成或由廊道连接起来的嵌入城市的区域(图8-1、8-2);板块又分为两类。1)受体区:用于非正规居住的场地,在那里自建社区有望繁荣发展;2)变革区:能够维持多种用途的区域,与廊道一起将IA与非辅助的非正规住区以及场地和服务项目区分开。

8-1 板块综合分析图Composite diagram of Receptor and Productive Patches8-2 为哥伦比亚的拉萨巴纳波哥大提供保护湿地的生产性板块(温室)Proposal of Productive Patches (for green houses) with protected wetlands for La Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia

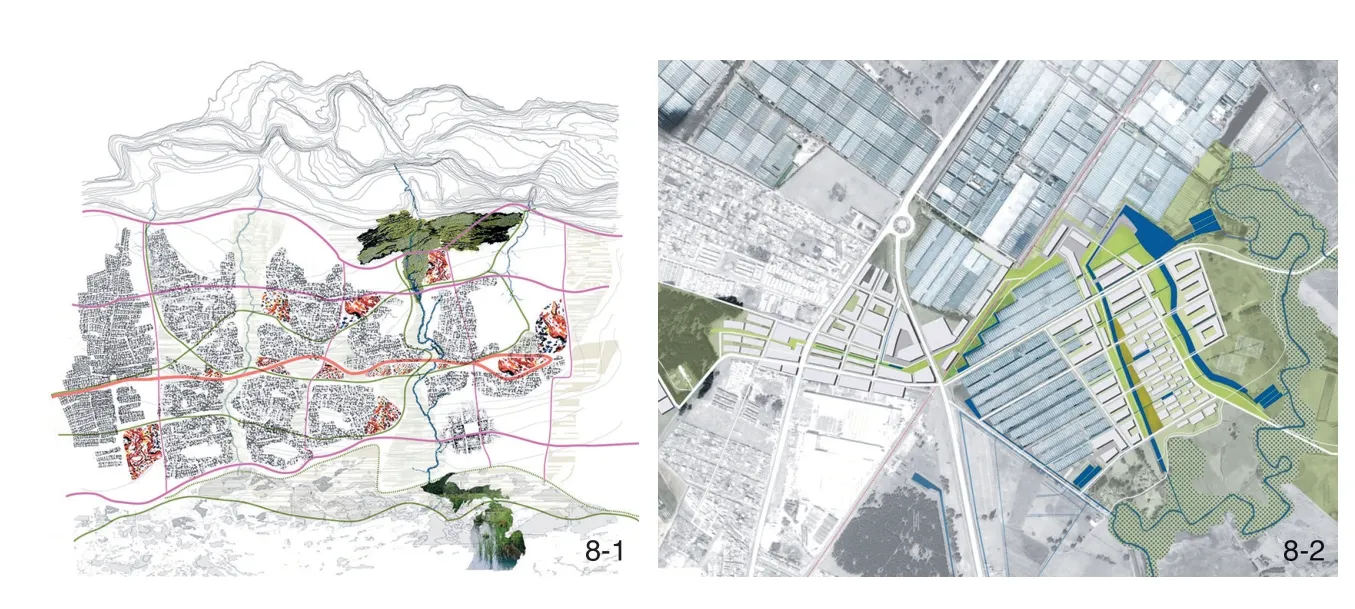

保育者:可能出现在上述所有的类别中,以确保所需空间的可使用性,随着IA作用区域的演化逐步适应城市需求(图9-1、9-2)。IA方法成功的难点之一是预留必要的空间,以逐步引入更多更复杂的城市功能,在住区里逐步完善服务和基础设施。如果这些空间得不到保障,未来的巨型非正规城市将会形成一个以住宅为主、由一些本地商业和服务拼接而成的“百家被”。这些非正规住区(的居民)将继续遭受交通堵塞、生产性工作机会受限、大都市服务和便利设施以及广阔的开放空间缺乏等问题的困扰。从墨西哥城、拉各斯、利马、亚的斯亚贝巴或加拉加斯可预见的不断下降的生活条件,可以窥见未来无人援助、不完整和边缘的大型非正规城市的状况。

9-1 廊道和板块之上的保育者分析图Composite diagram of Corridors, Patches, and Stewards9-2 文化和娱乐设施充当废弃采石场保育者的提案(哥伦比亚波哥大)Proposal for cultural and recreational facilities as Stewards on an extinct quarry, in Bogotá, Colombia

小尺度上的操作需要大尺度支持才能充分发挥作用。在正规的规划中,这些空间在被需要之前只是被分区保护。但在没有指导的非正规城市,免费的土地是一种非常理想的商品,主要用于自建房屋。IA提议保持土地可用的最佳方法是引入临时用途,这些临时用途必须对处于不同演变阶段的社区有意义。同时,IA应该对值得信赖的社区、机构或者街区的“保育者”进行管理。在改造这些空间以适应不断变化的需求的过程中,“保育者”也扮演着关键的角色,与IA培育的地区的倡导者携手合作。空间改造的规模、用途和形态,以及与城市发展进程相关的不同组件,将应对不同背景下的文化、管理和经济条件。此外,它们需要技术援助或公众参与。然而,正如笔者在本文中所指出的,社区本身就可以处理住房以及社区尺度的问题。城市的其他组件则需要特定公共部门或专业机构的支持。

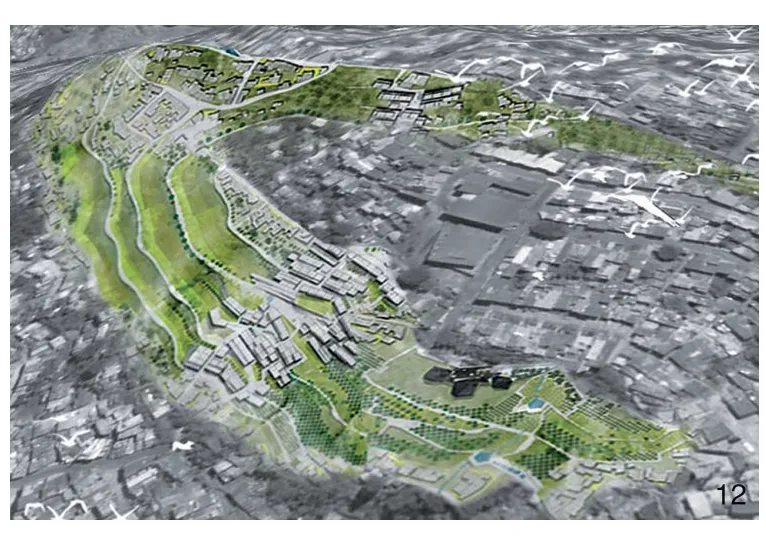

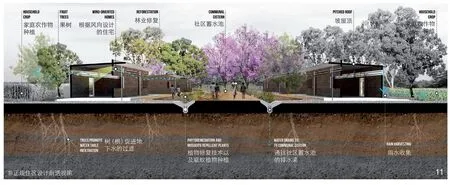

非正规框架规划设计方法是《未来非正规住区规划与设计:塑造自建城市》一书的核心,即塑造自我建设的城市,是对政治家、学者、专业人士、机构、私营部门和社区等紧急采取行动的呼吁,旨在以一种简单而坚定的方式来管理刚刚崛起的非正规城市,播种一个可持续的未来。笔者真诚地希望它能引起那些有责任、有手段、有能力在发展中城市引起城市变化的人的注意,并激励他们实施试点项目来证明IA的有效性(图10~12)。这本书里囊括了很多学术范例,以用于阐明这一手法在不同的实体空间和表现条件上能够处理的各种问题。它还指出了IA需要进一步的实验和研究⑥。

10 由宾夕法尼亚大学设计学院的学生设计的测试非正规框架规划设计方法的提案:在津巴布韦哈拉雷市奇通维扎的非正规/正规扩张研究Academic proposals testing the Informal Armatures Approach by students of PennDesign/University of Pennsylvania: Armatures for Informal/Formal Expansion in Chitungwiza, Harare, Zimbabwe

11 由宾夕法尼亚大学设计学院的学生设计的测试非正规框架规划设计方法的提案:为津巴布韦哈拉雷市的霍普利农场设计的公共空间和社区框架Academic proposals testing the Informal Armatures Approach by students of PennDesign/University of Pennsylvania: Proposal for public spaces and neighborhood frameworks for Hopley Farms, Harare,Zimbabwe,

12 由宾夕法尼亚大学设计学院的学生设计的测试非正规框架规划设计方法的提案:重新安置目前居住在不稳定地区上的居住者(哥伦比亚麦德林巴里圣多明哥)Academic proposals testing the Informal Armatures Approach, by students of PennDesign/University of Pennsylvania: Armatures to relocate settlers currently on unstable land, Barrio Santo Domingo, Medellín,Colombia

生活在发展中国家的数十亿人的生活受到几十年前引入的规划和设计模式的影响。同样,更多的人的生活将因无所作为而受到不利影响。IA旨在证明,这是一种可以改变现状的可行且合理的方法。现在是时候采取紧急有效的行动了。

注释:

① 有关贫民窟暴力来源和类型的详细统计数据详见参考文献[1]。

② 对于来自城市不平等的问题纠正详见参考文献[3]。

③ 有关该计划的更多信息,请参见参考文献[5]。

④ 有关如何使这些案例与改善非正规住区相关的更多信息,请参见参考文献[7]。

⑤ 麦德林从包括纽约和特拉维夫在内的入围城市中获得了由《华尔街日报》和花旗集团于2013年组织的“年度创新城市”竞赛,成为今年最具创造力的城市。几十年来,麦德林一直被认为是世界上最暴力的城市。麦德林举例说明,即使在最不利的条件下,城市的改善也有可能,而且在很短的时间内可以成为许多发展中国家的参考,特别是在改善非正规住区方面。参见参考文献[10]。

⑥ 《未来非正规住区规划与设计:塑造自建城市》一书的编辑、更新和扩展版将于2022年在中国出版(中文),其中的差异将解释非正规框架规划设计方法对快速发展的亚洲城市的适用性。

图片来源:

图1©卡洛斯·伊垂亚高;图2-1、6©戴维·加弗努尔,图2-2、4-1©加拉加斯纪念馆/城市文化基金会;图3设计:都市大学的学生,指导教授:戴维·加弗努尔,课程协调管理、渲染和照片:路易斯·萨利;图4-2©大卫·马埃斯特罗;图5-1©赫尔曼·桑佩尔,图5-2©卡特琳娜·桑佩尔;图7作者:梅根·塔拉罗斯基和彼得·巴纳德,指导老师:戴维·加弗努尔和塔博·兰内耶;图8作者:塔玛拉·亨利,指导教师:戴维·加弗努尔和阿布达拉·塔贝特;图9作者瑞秋·埃亨,指导教师:戴维·加弗努尔和阿布达拉·塔贝特;图10作者:丹尼尔·萨恩斯,指导教师:戴维·加弗努尔和塔博·伦内耶;图11作者:莱昂纳多·罗布雷托,指导教师:戴维·加弗努尔和塔博·伦内耶;图12作者:金伯利·库珀、丽贝卡·富克斯和凯亚·昆特,指导教师:戴维·加弗努尔和特雷弗·李。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

The Informal Armature Approach

Author: (USA) David Gouverneur Translator: ZHANG Chendi

1 Biases Against the Informal City

Why have we been so ineffective in dealing with the predominantly informal city? Close to a billion people live in self-constructed districts and another billion will live in similar conditions over the next three decades[1]①(Fig. 1). Yet, politicians,academics, and professionals often have biases that prevent appreciation for positive aspects of the informal city and consequently deter helping them from achieving better urban standards.

The cultural values of the more affluent and politically dominant tend to differ from the idiosyncrasies and financial possibilities of the urban poor. The negative attitude of the politicians,professionals and middle and upper classes stems from a lack of understanding of the causes that induce the emergence of informal communities.Residents of the formal city often consider informal settlements alien and a threat to their standards of living, but in many cases they have not even been in informal settlements.

My homeland Venezuela, which is collapsing economically after 20 years of a failed Socialist Revolution, offers an example of this orientation.While the political agenda, in theory, caters to the less-affluent segment of the population,government officials and ordinary citizens often mention “to consolidate barrios (how informal settlements are called in Caribbean nations)is to consolidate misery.” Another common statement is “We must substitute these unfit areas by providing dignified housing”. In my opinion,both statements reflect a misunderstanding of the dynamics of informal urbanization. Here, the informal settlements have been neglected, and only a fraction of the demand for new homes has been covered by social housing programs.

Even though there are many examples in different continents that have demonstrated the viability of improving living conditions in existing informal settlements, there are still countries,particularly those with highly centralized and authoritarian forms of government, in which eviction and destruction of self-constructed informal settlements are still the norms. Such was the case in Zimbabwe, where as recently as 2008, large informal settlements housing close to 800,000 people were razed. Here, for the most part, no alternatives were offered for the displaced settlers[2]. Consequently, the settlers ended up in neighboring South Africa, some returned to their rural areas of origin, or reinitiated a process of informal occupation on other sites. Forceful actions of this nature may liberate the sites intended for other uses from settlers; but they are a violent disruption for those who have occupied these locations, causing them to squat elsewhere with increased social resentment and sense of insecurity due to the possibility of future evictions.In more affluent developing nations, as in the case of China, urban renewal operations are very common. These projects have destroyed entire informal and traditional urban areas (referred in China as villages), forcing residents to live in distant sites where they must adapt to entirely different conditions in high-rise residential complexes. In the process, these projects erode local lifestyles and traditions. Such evictions are also associated with the loss of valuable agricultural land and natural habitats, as well as of cultural practices that enabled communities to respect the forces of nature and reduce risks.

2 Pros and Cons of Informal Urbanism

Many of the less affluent have no other option than to self-construct their dwellings and neighborhoods. They cannot access the formal realestate markets, or afford the costs associated with formal housing, even when those highly-subsidized programs. Migrants arriving in the cities from rural areas or smaller towns or seeking to relocate from existing informal areas of larger cities, do not have stable jobs, fixed income, or savings. They cannot meet the conditions that are indispensable to make them eligible to obtain mortgages or other forms of subsidies to acquire a home, or to rent one.Therefore, their only option is to illegally occupy a lot of undeveloped land, or to buy it at a price they can afford from illegal or “pirate” developers.Gradually, in a piecemeal process, the rustic shelters transform into more stable dwellings. They are often more than homes. They perform as living organisms, which grow to incorporate extended families, rental units, and productive activities such as small shops or manufacturing.

In most cases, residents of informal settlements do not pay for utilities, such as electricity or water, nor for property taxes or for commercial licenses. In later phases of consolidation, basic communal services as schools or daycare centers are provided by the city or NGO’s. Social ties are also very strong within self-constructed neighborhoods,and the sense of place and identity are usually much stronger than in any planned social housing program. All these factors represent enormous advantages for the informal dwellers. While informal logic offers many benefits, informal settlements are far from being problem-free. There is an accumulated and escalating social debt in the self-constructed cities of the developing world.The lack of opportunities to access information,education, health services, or knowledge of how to take better advantage of the commercial networks,keeps many residents of informal settlements at disadvantage in relation to formal city dwellers[3-4]②.While there are many creative examples of how prosperous economic enterprises have emerged within informality, this is not the norm.

Conditions may vary greatly from one country, city, or district to another, but settlements frequently lack fundamental urban conditions that are made available through the public sector, directly or indirectly (Fig. 2-1, 2-2). These deficiencies are reflected in:

1) Unsafe locations, like floodplains, very steep slopes, brownfields, and geologically unstable land, periodically leading to the loss of lives and properties as well as of environmental assets,such as deforestation, destruction of watersheds,soil erosion, contamination of aquifers, loss of biodiversity, etc.

2) Lack of infrastructure, particularly of potable water and sewers, which translates into public health problems.

3) Poor community services, such as education, medical assistance, sports facilities,recreational amenities.

4) Deficient public transportation, accessibility,mobility, and connectivity within the informal areas,and with the formal city. These factors contribute to spatial segregation and make it difficult for settlers to access jobs and services in the formal city, while impeding the provision of basic urban services in the settlements, as police surveillance,the access of ambulances, firefighters, garbage collection, etc.

5) Scarce or non-existent public places, other than narrow streets or pedestrian paths, that reduce the possibility of socialization and leisure.

6) Increased social resentment. These conditions may lead to violence, insecurity and crime, indicators which are perceived by the residents of both those informal settlements and in formal areas as the greatest concern and indicators of poor urban standards.

It is important to keep in mind that such urban problems tend to magnify as the settlements become larger, denser, and occupy sites further away from the older informal areas and from the formal city. To reduce urban disparities between the formal and the informal city, and ease escalating social tensions, a new set of planning, design, managerial paradigms are urgently required.

3 Attempt to Deal with the Growth of the Informal City

In the majority of developing countries,modernization and industrialization brought about significant demographic changes. In search of better income and services, the rural population migrated to the cities in large numbers. In some cases, migrations were the result of armed, ethnic,religious conflicts, violence, or famine.

Governments tend to respond to the initial informal settlements by ignoring them or keeping them away from “desirable locations” (Fig. 3).Over time, authorities realize that the processes of informal urbanization can’t be halted. In response,they try to plan for city growth, advancing social housing programs, “Site and Services” initiatives,or developing projects for the improvement of the settlements. As will be explained, these approaches have succeeded at various degrees, but also have limitations, in light of the rapid population growth,the magnitude of the self-constructed areas, and the complexities of developing cities. The following sections explain some of the deficiencies of these attempted solutions.

3.1 Unwanted Effects Derived from Traditional Urban Planning

In most developing nations, public agencies produce plans to guide urban growth. These planning instruments do not differ much from those that were originated and applied in industrialized nations from the second half of the 20th Century on. Such plans focus mainly on demographic projections which envision how and where the city should expand. They suggest densities and land uses associated with the provision of infrastructure, mobility systems, and services. These instruments are typically generic tools that do not take into account the contextual and cultural conditions of developing nations. Nor do they address informal growth. In the best of cases, they simply map and legally acknowledge the existence of the informal settlements, but certainly do not plan for new ones.

Moreover, these plans may have an undesirable effect on where and how informal areas grow.Most developing countries inherit a colonial legacy of inequitable land ownership patterns where properties are concentrated in the hands of a few. Public land is thus limited or in some cases nonexistent, which is required to steer the growth of settlements for the less-affluent segments of the population. As soon as the planning instruments are enacted, they transform rural land into urban land, sparking the real-estate market.

Governments then supply infrastructures,such as roads and potable water and sewers,creating additional value on private land, normally with no mechanisms to recapture this added value.And as has been mentioned, the less-affluent segment of the population cannot enter the formal real-estate market and are forced to settle on undesirable and poorly serviced sites, usually outside the urban boundaries established by the planning instruments.

3.2 Social Housing Cannot Cope with the Demand, and may Foster Urban Problems

Social housing programs are often aimed at relocating existing informal settlements or to dealing with the waves of new migrants. This occurs, particularly in the early phases of informal urbanization, when authorities still believe that they can eradicate them, or avoid their growth.Furthermore, social housing projects force settlers to adapt to different living conditions, leaving behind their cultural/rural practices. Formal housing projects also impedes them from taking advantage of the flexibility offered by the informal dwellings.

Additionally, public housing policies usually focus on the number of units that are provided,and not on the urban conditions that could make them sustainable habitats. Seeking cheap land,public agencies, or publicly assisted developers construct on the urban fringe, far away from jobs,services and transportation. Thus, these projects many times increase urban sprawl and social isolation. Even in wealthier developing nations,which are capable of providing heavily subsidized housing, the numbers of settlers who self-construct their homes gradually surpass those who access the public or public/private housing developments.Social housing is not a solution for those who cannot afford it.

4 Successful Plans for Improvement of Informal Settlements may also Have Limitations

Academia, the public sector, and various institutions gradually have recognized that a large portion of the population occupies selfconstructed areas. Knowing that they are here to stay, they acknowledge that informal settlements require attention. Local professionals frequently lack training and practical expertise on how to deal with informality.

However, perceptions towards informality have changed in numerous developing countries.As those living in the informal become the majority of the population, they have gained increasing political leverage. Consequently, many nations,like Venezuela, Brazil, Colombia, have introduced changes in their legal frameworks that regulate territorial and city planning, acknowledging informal occupation and offering norms and criteria on how to improve existing informal areas.Initially, they are simple urban interventions, such as paving roads and paths/staircases in settlements located on steep sites, installing utilities or drains for sewage, or building schools and basic medical facilities (Fig 4-1, 4-2). Officials also grant land ownership titles. While settlers welcome these initiatives, they are minor accomplishments that fall short in significantly altering living conditions in these neighborhoods. As a result, the informal districts remain in disadvantaged in relation to the formal city.

In the 1990s I was National Director of Urban Development of Venezuela. During that time, I supported a group of talented researchers, including Teolinda Bolívar, Josefina Baldó and Federico Villanueva. These researchers were perhaps the first in the region to warn of the consequences of inaction concerning informality. The Plan for the Improvement of Informal Settlements in Caracas which I was able to assist from my public position reflected their findings[5-6]③. In less than a year, the team produced a large amount of technical information.A few years later, when Hugo Chavez assumed his fist mandate, Professor Baldó was named the President of the Venezuelan Housing Council.Baldó made plans for the improvement of informal settlements a national priority and organized hundreds of competitions to begin their implementation. However, the influential military sector still had a persistent bias against initiatives focused on informal settlements. Additionally, the top-down governmental organization limited the implementation of such efforts.

Despite these shortcomings in Venezuela, the past decades have been characterized by cuttingedge practical experiences in this direction in other nations. Valuable information, working methods,and design criteria are being shared and adapted to various contexts. In different South American countries and in South Africa there have been very important initiatives conceived as holistic rehabilitation projects. Notable are those in Brazil,Colombia, Bolivia and other Andean Nations[7-9]④.

Perhaps the most notable example is the world-renown—and many times awarded—improvement projects in the city of Medellín,Colombia. Only three decades ago, Medellín ranked as the most violent city in the world. Statistics revealed that the highest percentage of violent crime was concentrated in the informal areas at the almost inaccessible mountain-tops[10]⑤. In April 2014, the city hosted the World Urban Forum.Participants from all over the world were able to appreciate how creative design and transparency in the management of urban change could improve living conditions in the most distressed areas. The availability of municipal funding and technical expertise in Medellin may surpass those available in most developing cities. However, the main factors that contributed to Medellín’s success were:

1) Political commitment to address an accumulated social debt of decades of exclusion,exacerbated by deep-rooted violence.

2) Authorities making informal settlements upgrading programs the main course of action and envisioning them as part of a wider urban strategy.

3) Community engagement in all phases of planning, design, construction, operation, and maintenance of the projects.

4) The organization of efficient, knowledgeable,and honest teams, capable of delivering highquality design solutions, and providing sustained management to the programs.

Despite, these gratifying outcomes, there is also a limit of what can be achieved when trying to match living conditions in the informal city to those present in the formal urban areas. Acting on highly consolidated settlements is a laborious process.To introduce open spaces, improve connectivity,infrastructure, and communal services, or relocate settlers from high-risk areas requires substitution housing. Relocations require complex negotiation skills. It is not easy to find land to construct relocation housing in the same neighborhoods or in adjacent areas. Furthermore, those who have to be relocated must be willing to move.

The urban improvements within existing settlements seem to work well at a neighborhood scale, but the spatial limitations hamper efforts at addressing greater urban/metropolitan demands.For example, it is very difficult to provide services,infrastructure, uses, and public spaces such as large parks, technical schools, universities, food distribution and transportation centers, hospitals,large sport facilities, manufacturing and industrial areas, and so on, within highly consolidated and dense settlements. Even the best plans for the rehabilitation of informal settlements also has limitations dealing with the demands of much larger self-constructed districts and cities, which are becoming the norm worldwide.

It is also important mentioning that there is a strong resistance to support the development of new informal areas. This even occurs within contexts where the legal system and common practices favor the improvement of existing informal settlements, and have been successful in implementing them, and even when the authorities acknowledge that informal urbanism cannot be deterred④.

The following sections of this article focus on how to deal with the growth of the predominantly informal city in a preventive and sustainable manner. I will refer briefly to the Site and Services programs, as a precursor of the Informal Armatures approach. I then suggest IA as an alternative method to deal with contemporary challenges of informality and balanced urban growth.

5 Sites and Services: Frameworks for Self-constructed Housing

As early as the 1960’s, it became evident to a group of socially concerned academics, researchers and professionals that conventional urban planning and social housing programs could not meet the growing demands of shelter for the less affluent.This group included authors and designers who are now frequently cited or referred to in studies on urban planning and design, such as Horacio Caminos, John Turner, Peter Land, and Germán Samper. They advanced ideas and projects that came to be known as the Site and Services programs. The notion was simple: settlers know how to occupy a plot of land and gradually build, expand and upgrade their dwellings. Settlers cannot achieve the urban conditions that normally require support from the public sector, professionals, institutions,or communally driven organizations. The goal then was to provide a balanced habitat, which included the following: access to appropriate sites,urban layouts with lot subdivisions, infrastructure,and open spaces where communal services and amenities would gradually be incorporated.

These authors passed on the torch to thousands of their students who then became active professionals, taking important positions in leading academic, finance, and planning institutions worldwide. The scope of Site and Services programs varied according to the financial,managerial and design assets of the different locations. In some cases, it included the provision of basic housing shells, or a combined bathroom and kitchen unit, accompanied by plans and technical assistance to guide the expansion and improvement process. In other instances, they envisioned assisting the community by providing skills and financing to locally produce low-cost construction materials and user-friendly building methods.

Perhaps one of the most emblematic of such initiative was the 1965 PREVI competition(Fig. 5-1, 5-2), organized for the urbanization of a large tract of vacant land in the South of Lima,Peru. Professor Peter Land coordinated PREVI,which called for distinguished planners and designers from different continents to participate. Professor Land’s drive and the support of the Peruvian President at the time, architect Fernando Belaúnde Terry, facilitated the implementation of the project.In PREVI, a larger urban framework tied together different design proposals for the neighborhoods,which were developed according to the winning schemes of the competition.

I visited PREVI a few years ago and was able to see the quality of the homes and the communal spaces 45 years after the project had been envisioned. However, PREVI is only a small site in a very large territory where over 2.5 million lived predominantly in informal settlements. For most inhabitants of PREVI, essential city services,amenities, and jobs are to be found in the formal city. They still must travel for more than an hour and a half, passing through a continuum of substandard informal areas.

I had also been several times in Medellín from 2008 on, appreciating the ongoing, multi-layered processes that radically improved their informal neighborhoods. This initiative occurred under the leadership of Mayor Sergio Fajardo and technical coordination of Alejandro Echeverri. These areas have continued to thrive in the following administrations. I had also taken my students on trips to Medellín and dedicated several semesters formulating proposals which envisioned the sustainable growth of new self-constructed areas.These projects were intended to go a step beyond,in scale and performance, concerning the Site and Services programs.

Approaches in Lima and Medellín contrast sharply. In Lima, the provision of a preemptive urban framework, working at a district/neighborhood scale is now engulfed by a large unplanned informal territory. In Medellín, the projects could be considered a sort of corrective urban surgery, operating on existing informal settlements which are part of a wider urban strategy. These different initiatives provided pivotal insight explored in my aforementioned book④.In this publication, I introduce the Informal Armatures Approach (Fig. 6).

6 The Informal Armature Approach(IA)

Since the emergence of the Site and Services programs in the 1960s, not much has been done in terms of thinking ahead and acting on the growth of self-constructed settlements. We are in urgent need of new paradigms to foster new informal urban growth. We must implement methods,utilizing tools capable of tapping the potentials of informality and engaging with the communities that self-construct their habitats. This should be done keeping in mind that in many cases we are seeding very large and complex urban areas. We should draw upon innovative design and performative ideas. Our aim should be to steer the predominantly informal cities to higher levels of performance and help their residents attain decent living conditions.

How is the IA different from previous methods? The IA is intended to be simple in its principles, design ideas, and applicability. It aims for compelling results. It suggests a symbiosis between the formal and the informal modes of city-making, which can result in rich and dynamic urban ecosystems that are highly competitive and resilient④. The key conditions of the IA approach are as follows: Preemptive and Transformative,Physical and Performative, Hybrid and Multi-scale Operations, Environmentally Friendly, and Simple.These conditions are all closely interrelated. IA is based on flexible design components adaptable to different site conditions.

6.1 Preemptive and Transformative

IA is essentially a preemptive planning and design method that aims to foster the growth of the predominantly informal city. It intends to serve as a support system enhancing the internal dynamism of informal urbanization. The main premise is that planning and guiding the urbanization process allows for more balanced and efficient development. This contrasts to retrofitting consolidated informal neighborhoods. For the IA to be effective, the following conditions must be met: 1) Political acceptance that unassisted informality will occur on its own, occupying inadequate locations without the basic urban frameworks, and thus will result in difficult urban situations with severe social and environmental implications, 2) The availability of suitable public land to apply the approach, the will, and capability of the public sector to assemble it, acquire it, or to develop it in partnership with the private sector,and 3) The organization of teams of facilitators,committed to the IA initiative. The teams must also have the ability to adapt the IA criteria to local conditions, engage the community, incorporate expertise according to particular needs, and foster the transformation of the IA sites till their assistance is no longer necessary.

6.2 Physical and Performative

Traditional planning in most developing countries is reduced to static land use plans with no design considerations; they are centered on controlling the real estate market which has no incidence on informal urbanism. Developing countries frequently blame their problems and the inability to cope with them on the lack of financial resources. While there certainly may be economic limitations, greater weaknesses in these nations stem from the lack of coherent visions to establish priorities, coordinate actions, and ensure efficiency and transparency. Medellín points to the importance of introducing cutting edge planning and design standards, with efficient and sustained management, and working hand in hand with the communities as the best way to ensure deliverance and accountability.

Thus, the IA approach combines notions of spatial organization and design criteria with on-site management. It suggests how to foresee simple spatial organization patterns to attract and guide the initial occupation of the sites and create a strong bond with the settlers. The strength of the approach relies greatly on establishing trust between the facilitators of the program and the communities, and also in the way urban changes are managed. The transformations of the IA territories will occur not only in the public realm, but also in the appropriately timed inclusion of a diversity of uses that are meant to supplement the selfconstructed areas, as the communities consolidate,evolve, have greater expectations, and become part of much larger urban agglomerations.

One of the main lessons gained from the Site and Services programs and the informal settlement improvement plans is that spatial organization and physicality of the self-constructed city is important.Sustainable urbanism requires quality planning and design. This may include designing compelling and performative urban landscapes, facilitating entrepreneurship, dismissing energy composition and waste, enhancing social interaction, reducing violence, favoring shared participatory governance,and so on. Facilitators of the IA should have the ability to make the early settlers feel that they are a proactive part of improving their districts and help them engage in all facets of the foundation and evolution of the settlements.

6.3 Hybrid and Multi-scalar Operations

Both the Site and Services and the informal settlements improvement projects seek to merge the dynamics of the self-constructed with planning and design. IA operates with the same logic, but its goal is to attain a highly balanced and competitive urban product that will, in time, become the mainstream,as the dominant form of urbanization in many developing countries will be informal settlements.To do so, IA facilitators must develop the skills to deal with early phases of occupation, deploying rather simple design components in accordance with the basic needs of the new settlers, while simultaneously planning and be preparing to address the urban and metropolitan demands of larger urban ensembles. This is not an easy task; it requires skilled “navigators”.

Tracks of land for self-constructed dwellings which can be subjected to different types of urban frameworks and technical assistance, as the Sites and Service programs envisioned - accompanied by other forms of social housing - are very important components of the IA fostered territories, but far from the only ones. The IA initiative considers strands and patches of vacant land that may initially incorporate simple mobility systems, or allow for the installation of reception tents with a provisional supply of potable water. These open spaces may eventually sustain an efficient public transportation system, and a diversity of uses,civic amenities, and compelling public spaces. The IA program may also predefine how to protect waterways and vegetated areas that will become the recreational corridors of the city, or envision sites initially employed as recycling centers in order to obtain construction materials to assist the settlers in building their shelters. There may be areas that will serve to initiate urban agricultural programs that,in time, will give way to manufacturing centers,technical schools, large city markets, and so on.

Some land with temporary uses may be kept in public hands till the aspirations and income levels of the community demands rise. The private sector then can be called in to provide more sophisticated commercial areas and amenities.These operations may represent opportunities for the IA facilitators to attract private investment targeting mixed use/residential developments for higher income groups, providing formal housing,offices, cinemas, recreational facilities which the original settlers will also demand. The additional value obtained down the line from such operations will help the IA facilitators generate revenues to reinvest in other services within the same territories or reinitiate similar IA initiatives in new urban frontiers. These IA-managed districts are expected to thrive with the vitality and character of the selfconstructed combined with the amenities of the formal city, as a true hybrid product.

6.4 Environmentally Friendly

Responsive contemporary urbanism must address environmental aspects that are pivotal not only for the wellbeing of the communities but also for the health of the planet. Such considerations were not in the agenda of conventional urban planning which still determines the urban conditions of the formal city in many developing countries, nor were they considered in the Site and Services programs as precursors of the IA approach.

Since IA begins operating before occupation takes place and determines the first physical and performative conditions of the settlements, it represents a favorable and still flexible milieu to introduce environmentally friendly criteria. Among some of the most sensitive aspects we can mention mechanisms to protect adjacent watersheds,areas of biodiversity, valuable agricultural soils,the hydrological network -adjacent to and within the urban areas-. Similarly, IA can facilitate the introduction of green infrastructure, pedestrian and clean public transportations networks, recycling programs, community agricultural gardens, etc. The presence of pro-active IA facilitators will allow the planning, design, and management of the new informal/formal districts with these ideas in mind,making them meaningful for the early settlers as part of their daily lives. It is important to keep in mind those in non-fostered informal settlements,particularly in primal phases of occupation when they are in survival mode, settlers cannot be aware of or care for environmental issues. Many of them have arrived from rural areas, and quickly lose their agrarian skills and familiarity with nature as they become urbanites. The IA allows accommodating these cultural practices in the new urban settings.

6.5 Simple: Based on Flexible Design Components,Adaptable to Different Site Conditions

Throughout history, cities have been experimenting in testing new urban organizations.Some were shaped by prototypes embedded in cultural practices, and others introduced by the vision of leaders, designers, economic interest groups, providers of services, etc. Design solutions are often replicated in contexts different from those in which they originated. Those that prevail tend to be simple in the manner they are spatialized and implemented. Commonly planning and design prototypes used in the developing world respond to particular ideologies and political, economic, and social goals of the elites, but do not always benefit the majority of the population. IA sets forwards a toolkit of simple design components whose main goal is to provide better living conditions for the most numerous segments of the population of the developing world, the poor. These components are not dogmatic in their nature, scale, or in their morphological and performative qualities.Rather they embed principles that can sustain the multiple processes mentioned in the preceding sections. Their successful deployment as spatial/performative solutions will depend on the local contextual and cultural nuances, and of the ability of the IA facilitators to engage the communities and other urban actors in the initiatives.

To simplify its application, the IA approach classifies the design components into the following categories: Corridors, Patches, and Stewards. These components are expected to act as urban organizers of an integrated system, supporting the informal processes and performing different roles.

The Corridors are essentially linear components or strands that structure the public realm, acting as the skeleton and DNA of the systems of open spaces, infrastructure, mobility systems, water management devices, services, and so on. The Corridors are subdivided into two sub-categories:

1) Attractors: acts as pullers or hot spots encouraging the concentration of the population and activities towards areas where it is more appropriate to do so, providing spatial and managerial conditions to better handle them, and 2) Protectors: contrarily, dissipate urban energy,safeguarding environmental assists, and acting as buffers to avoid urban occupation/expansionwhether informal or formal- from sensitive areas.

Attractors and Protectors are expected to manage a high percentage of the transformations of the settlements into larger districts and urban territories and require a higher degree of public involvement to achieve their goals, particularly in the early stages of occupation, consolidation, and growth (Fig. 7-1, 7-2).

Patches: represent the areas of urban infill that are nurtured or held together by the Corridors(Fig. 8-1, 8-2); they are also grouped into two subcategories,

1) Receptors: are sites made available for informal occupation, where the self-constructed neighborhood are expected to flourish; and 2) Transformers: areas capable of sustaining a multiplicity of uses that, together with the Corridors, are expected to differentiate the IA from the non-assisted informal settlements and the Site and Services programs.

Stewards: which are components, that may appear in all the previous categories to ensure the availability of space needed to gradually accommodate the urban demands, as the IA territories evolve (Fig. 9-1, 9-2). One of the difficult tasks for the success of the IA approach is to secure the spatial requirements to gradually introduce more complex urban uses, services and infrastructure at more mature stages of consolidation of the settlements, according to the economies of scale associated with much a larger population and urban areas. If these spaces are not secured, the mega-informal cities of the future will result in a quilt of predominantly residential patches with some local commerce and services.They will continue to suffer from strangled mobility, limited productive jobs, in addition to lack of metropolitan services and amenities and large open spaces. The current living conditions and the diminished performance of Mexico City, Lagos,Lima, Addis Abeba, or Caracas provide a glimpse into the future of the unassisted, incomplete, and marginal mega informal cities.

The small scale requires the large one to adequately perform. In formal planning, these spaces are simply safeguarded by zoning, until they are required. But in the unguided informal city, free land is a highly desirable commodity, to be used mainly to self-construct homes. IA suggests that the best way to keep the land available is to introduce provisional uses which must be meaningful for the communities in the different levels of evolution of the settlements accompanied by trusted communal or institutional or neighborhood “custodians”that will establish stewardship over them. The Custodians also play a pivotal role working hand in hand with the facilitators of the IA fostered territories, in the process of retrofitting these spaces to respond to changing demands. The scale,uses, and morphologies, as well as the associated urban processes of the different components,will depend on the cultural, managerial, and economic conditions in each context. In addition,they require technical assistance or public involvement. However, as I have argued in this article, communities alone can handle the housing/neighborhood scale. The other urban components demand some sort of public or institutional support.

The Informal Armatures approach, at the core of the book Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements: Shaping the Self-Constructed City is a call for urgent action, directed to politicians, academics, professionals, institutions,the private sector and communities alike, to embark in a simple but committed way in stewarding the informal city that is just emerging today, seeding a sustainable future. I sincerely hope that it will call the attention of those who have the responsibility,the means, and the ability to induce urban changes in developing cities, motivating them to implement pilot projects to prove its validity (Fig. 10-12). The book includes academic examples illustrating the physicality, and the performative conditions that the approach may handle, in very different contexts. It also suggests courses of further experimentation and research that the IA requires⑥.

The lives of billions living in the developing world is impacted by planning and design paradigms that were introduced decades ago.Similarly, the lives of many more will be adversely affected by inaction. IA aims to prove that it is a feasible and appropriate approach to make a real difference. Now is the time for urgent and efficient action.

Notes:

① For detailed statistic on sources and type of violence in the slums see reference [1].

② For issues derived from urban inequalities revise see reference [3].

③ For additional information on the Plan see reference [5].

④ For more information on what makes those cases particularly relevant in the context of working with informal settlement improvements, see reference [7].

⑤ Medellín received the ‘Innovative City of the Year’competition, organized in 2013 by The Wall Street Journal and Citi, as the most creative city of the year,from a shortlist that included New York City and Tel-Aviv.This was one of many prizes and praises that Medellín,considered for decades the most violent city in the world.Medellín exemplifies that even under the most adverse conditions urban improvement is possible, and in a short time, becoming a reference for many developing nations and particularly in relation to the improvement of informal settlements. See reference [10].

⑥ An edited, updated, and expanded version on Planning and Design for Future Informal Settlements: Shapping the Self-Constructed City, will be published in China (in Mandarin) in 2022, with variances that will explain the applicability of the Informal Armatures approach for fastgrowing Asian cities.

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1©Carlos Itriago; Fig. 2-1, 6©David Gouverneur,Fig. 2-2, 4-1©Caracas Cenital/Fundación para la Cultura Urbana; Fig. 3©students of Universidad Metropolitana.Advisor: David Gouverneur. Project coordinator, Rendering and Photo: Luis Sully; Fig. 4-2©David Maestres; Fig. 5-1©Germán Samper, Fig. 5-2©Catalina Samper; Fig. 7©Megan Talarowski and Peter Barnard. Advisor: David Gouverneur and Thabo Lenneiye; Fig. 8©Tamara Henry. Advisors: David Gouverneur and Abdallah Tabet; Fig. 9©Rachel Ahern. Advisors:David Gouverneur and Abdallah Tabet; Fig. 10©Daniel Saenz. Advisors: David Gouverneur and Thabo Lenneiye;Fig. 11©Leonardo Robleto. Advisors: David Gouverneur and Thabo Lenneiye; Fig. 12©Kimberly Cooper, Rebecca Fuchs and Keya Kunte. Advisors: David Gouverneur and Trevor Lee.

(Editor / LIU Yuxia)