Antioxidant and antigenotoxic properties of Alpinia galanga, Curcuma amada, and Curcuma caesia

2021-07-25AnishNagRiteshBanerjeePriyaGoswamiMaumitaBandyopadhyayAnitaMukherjee

Anish Nag, Ritesh Banerjee, Priya Goswami, Maumita Bandyopadhyay, Anita Mukherjee✉

1Department of Life Sciences, CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Bangalore, India

2UGC-CAS, Department of Botany, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Zingiberaceae; Antioxidants; Anti-genotoxic;Curcuma amada; Alpinia galanga; Curcuma caesia; Phytochemicals

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress, induced by various free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS), plays a vital role in the development of chronic diseases such as cancer, vascular diseases, hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy,neuro-genetic diseases, diabetes, aging, etc.[1,2]. Synthetic antioxidants are still controversial as they are thought to be linked with toxicity[3],leading to the mutation of genetic materials. The recent upsurge in the interest and popularity of natural antioxidants encouraged the food industry to continually look for natural antioxidants, with low toxicity and enhanced functional properties that can be consumed as a part of a balanced and healthy diet. Plants are rich in natural antioxidants and can significantly improve the quality of human life[4]. In this backdrop,plant-derived antioxidants are believed to be more potent and safe to use as they are harmless and readily available in nature.

The family Zingiberaceae comprises 53 genera and over 1 200 species. It is considered the powerhouse of active phytochemicals,which exhibit a wide range of biological effects, including antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, anti-aging, and anticancer activities[5]. The rhizomes are extensively used in traditional medicines and are also globally consumed as condiments and spices. Alpinia galanga (A. galanga), Curcuma amada (C. amada),and Curcuma caesia (C. caesia) are aromatic rhizomatous members of this family and were given particular emphasis by numerous researchers due to their vast range of active constituents phenolics,curcuminoids, and terpenoids, etc[6]. A. galanga is commonly known as ‘Kulanjan’ and has been used in folk medicines and food products. Mango ginger (C. amada) and black turmeric (C.caesia), on the other hand, are two prominent members of the genus Curcuma which are widely distributed in the tropics of Asia to Africa and Australia and traditionally used as spices and medicines by tribal communities. Recent studies on these plants have confirmed their various medicinal properties, which include antibacterial,antifungal, anti-inflammatory, and central nervous system depressant roles[7,8]. The correlation between their cytotoxic, genotoxic, and anti-genotoxic activity has been scarce despite the availability of the data associated with the role of these plant extracts as natural antioxidants. Nevertheless, oxidative damage to the DNA or other biomolecules such as protein, lipids may lead to severe implications for human health, even to cell death. Therefore, it is deemed essential to assess these plants’ genotoxicity and anti-genotoxicity to ensure their safety and efficacy.

Our present study was aimed to investigate the anti-genotoxic properties of ethanolic extracts of A. galanga, C. amada, and C.caesia rhizomes. The study also includes in vitro safety assessment as well as antioxidant profiling of the extracts to decipher the protective mechanism against oxidative stress. Moreover, an in vivo study was also conducted to validate the anti-genotoxic potential of the most active extract in the Swiss albino mice. Finally, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) analyses were performed to identify the potential bioactive compounds in the C. amada rhizome extract.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl free radical (DPPH, CAS no.1707-75-1), 2,2’-azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS) (CAS 30931-67-0), 2,4,6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) (CAS 3682-35-7), cyclophosphamide(CP) (CAS no. 6055-19-2), triton X-100 (CAS no. 9002-93-1),methyl methanesulfonate (MMS), Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA), Rhodamine 123, acridine orange, ethidium bromide, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ethanol was obtained from Merck Specialities (Pvt.) Ltd., India. Dimethyl sulfoxide was obtained from Qualigens, Mumbai, India. Normal melting point agarose and low melting point agarose were purchased from Invitrogen(Carlsbad, CA, USA). Other reagents like gallic acid, Evans blue,ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), tris buffer were purchased from Hi-Media, Mumbai, India. All other chemicals like hydrogen peroxide (HO), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), and sodium carbonate(NaCO) were purchased locally and were of analytical grade.

2.2. Plant materials and extraction

Plant material was collected from the medicinal garden of North Bengal University and the botanical garden of Calicut University,Calicut and maintained in the experimental garden of the University of Calcutta, Kolkata. Dried voucher specimens were submitted to the North Bengal University Herbarium with the accession numbers 09701 (C. amada), 09709 (C. caesia), and 09697 (A. galanga).

A total of 100 g of the dried rhizomes of C. amada, C. caesia,and A. galanga were soaked in 1 L of ethanol at room temperature(35.5 ℃) and kept in the dark for 7 d. The extracts were filtered and evaporated to dryness by a rotary evaporator[9]. After extraction, the extract yield was calculated using the following formula;

Extract yield = (EW/DW) × 100 Where EW is the extract weight, and DW is the dry weight. The yields after extraction are 6.99% for C. amada, 7% for C. caesia, and 9.56% for A. galanga. Dried extracts were collected in an airtight receptacle and stored at -20 ℃ for further experiments. For each extract, all the experiments were carried out in triplicates at each concentration.

2.3. Quantification of total polyphenol content (TPC)

The TPC of the extracts was determined according to the method of McDonald et al.[10] and Roy et al.[11] with minor modifications.A total of 0.5 mL rhizome extract (50 μg) of C. amada, C. caesia,and A. galanga was mixed with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent (5 mL,1:10 dilution with double distilled water) and further neutralized by aqueous NaCO(4 mL, 1 M) solution. The reaction mixture was then allowed to stand for 15 min at room temperature. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was read at 765 nm using a UVvisible spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). A standard curve was prepared using solutions of gallic acid (standard) in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-35 μg/mL, with different gallic acid concentrations (μg/mL) at x-axis and absorbance value at y-axis. The TPC was expressed in terms of mg of gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per g of extract (mg GAE/g), using the equation y= 0.088 7x-0.132 5, R=0.99.

2.4. Antioxidant properties

2.4.1. Ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) assay

The FRAP assay developed by Benzie and Strain[12] was performed with some modifications[13]. FRAP reagent (10 mL of 300 mM Naacetate buffer, pH 3.6; 1 mL of 10 mM TPTZ in 40 mM HCl and 1 mL of 20 mM FeCl) was prepared and pre-warmed at 37 ℃. Then 3 mL of this reagent was mixed with 100 μL of rhizome extracts from C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga (50 μg/mL). The reaction mixture was thoroughly vortexed, kept for 4 min, and the absorbance was read at 593 nm (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). A standard curve was prepared using solutions of ascorbic acid (standard) in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-10 μg/mL, with standard concentrations (μg/mL) at x-axis and absorbance value at y-axis. The FRAP value was expressed as mg of AAE per g of extract(mg AAE/g) from the standard curve equation y=0.012 4x-0.024 6,R=0.96. Each experiment was carried out in triplicates.

2.4.2. DPPH radical scavenging assay

The DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined using the method described by Lu et al[14]. Briefly, 10 μL of the rhizome extract (30, 60, and 120 μg/mL) was mixed with 3 mL of 6 × 10M DPPH in ethanol. After 30 min of incubation in the dark at room temperature, the absorbance at 517 nm was read (Beckman Coulter,CA, USA). The radical scavenging capacity (R%) of DPPH radical was calculated according to the formula:

R% = [(A- A) / A] × 100

Where, Ais the absorbance of the control solution (containing only DPPH), and Ais the absorbance in the presence of extracts.A standard curve was prepared using solutions of ascorbic acid(standard) in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-4 μg/mL. DPPH value was expressed as mg of AAE per g of extract (mg AAE/g) with the standard curve equation y=2.400 2x-9.909 6, R=0.95, where x= concentrations of the standard (μg/mL) and y= absorbance value at 517 nm.

2.4.3. ABTS radical scavenging assay

ABTS radical scavenging assay was carried out according to the method of Hassan et al.[15] with modifications. ABTS solution (7 mM) and potassium persulfate (2.45 mM) were mixed and allowed to stand for 14 h in the dark to generate an ABTScation solution.The mixture was diluted with 0.05% ethanol to obtain an absorbance of (0.70±0.02) at 734 nm. To 2 mL of this working ABTScation solution, 200 μL rhizome extract of C. amada, C. caesia, and A.galanga was added, and the mixture was vortexed for 45 s. The resulting absorbance was read at 734 nm using a spectrophotometer(Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). A standard curve was prepared using solutions of ascorbic acid (standard) in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-5 μg/mL. The ABTSscavenging activity was expressed in terms of mg of AAE per g of extract (mg AAE/g) from the standard curve equation y=0.474 2x+3.056 6, R=0.98; where x= concentrations of the standard (μg/mL) and y= absorbance value at 734 nm.

2.4.4. Hydroxyl radical scavenging (HRS) assay

HRS assay was performed according to the method of Halliwell and Gutteridge[16] with modifications[17]. The reaction mixture(1 mL) contained 100 μL of 28 mM 2-deoxyribose (dissolved in KHPO-KHPObuffer, pH 7.4), 500 μL of rhizome extracts from C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga in phosphate buffer (2.5, 5 and 10 μg/mL), 200 μL of 200 μM FeCl, 1.04 mM EDTA (1:1 v/v), 100 μL HO(1.0 mM) and 100 μL ascorbic acid (1.0 mM). All solutions were freshly prepared. After 1 h incubation at 37 ℃, the extent of deoxyribose degradation was measured by the TBA reaction. Then 1 mL of TBA (1% in 50 mM NaOH) and 1.0 mL of 2.8% TCA were added to the reaction mixture and heated at 100 ℃ in a water bath for 20 min. After cooling, the absorbance was read at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). The percentage inhibition (I %) of sugar degradation was calculated by the formula:I% = [1 - ( A/ A)] × 100 Where Ais the absorbance value in the presence of extracts,and Ais the absorbance value of the fully oxidized control. A standard curve was prepared using quercetin (standard) solutions in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-5 μg/mL. The hydroxyl radical scavenging value was expressed in terms of mg of quercetin equivalent (QE) per g of extract (mg QE/g) from the standard curve equation y=13.415x+5.691 3, R=0.95,where x= concentrations of the standard (μg/mL) and y= absorbance value at 532 nm.

2.4.5. Principal component analysis (PCA)

The TPC and antioxidant values (for example DPPH) were used as input variables for the analysis. The result of PCA discerned the relationship between the variables.

2.4.6. Hierarchial clustering analysis

The single coloured heat map and hierarchical clustering analysis were performed by Molecular Experiment Viewer 4.9.0 (MEV 4.9.0). Similar to the PCA, TPC and antioxidant values were used as inputs. The relationship among different variables was established in clusters, based on Pearson correlation principle.

2.5. Cell-free protection assays for biomolecules

2.5.1. Lipid peroxidation inhibition

To measure the inhibition of lipid peroxide formation upon exposure to extracts on egg yolk homogenate as lipid-rich media,a modified thiobarbituric acid reactive species assay was carried out[18]. Briefly, 0.5 mL of egg homogenate (10%, v/v) and 0.1 mL of each rhizome extract (C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga) at 30, 60, and 120 μg/mL concentrations were mixed, and the volume was made up to 1 mL with double distilled water. A total of 0.05 mL FeSO(0.07 M) was added to initiate lipid peroxidation, and the mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 30 min.Ascorbic acid (8 μg/mL) was used as a reference compound. After incubation, 1.5 mL of 20% acetic acid (pH 3.5) and 1.5 mL of 0.8%(w/v) TBA in 1.1% SDS were added. The resulting mixture was vortexed and then heated at 95 ℃ for 60 min in a water bath. After cooling, butan-1-ol (5 mL) was added to each tube and centrifuged at 3 000 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the organic upper layer was recorded at 532 nm using a spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter,CA, USA). Inhibition of lipid peroxidation (%) of the sample was calculated by the following formula:

Percentage inhibition of lipid peroxidation (%) = [(1 - E/C)] × 100

Where C is the absorbance value of the fully oxidized control, and E is the absorbance value in the presence of the sample. Further,a standard curve was prepared using solutions of ascorbic acid(standard) in ethanol with final concentrations in the reaction mix ranging from 0-8.5 μg/mL. The value was expressed in terms of mg of AAE per g of extract (mg AAE/g) with the standard curve equation y=5.744 3x+5.977 7, R=0.91, where x= concentrations of the standard (μg/mL) and y= absorbance value at 532 nm.

2.5.2. Protein oxidation inhibition

Inhibition of protein oxidation was evaluated following the method of Hu et al.[19] with modifications. BSA was oxidized by HO/Fe/ascorbic acid system. The reaction mixture (1 mL) containing 0.45 mL of C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga rhizome extract (2.5, 5 and 10 μg/mL in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), 0.2 mL BSA (10 mg/mL),0.2 mL of FeCl(1 mM), 0.05 mL of HO(80 mM), and 0.1 mL of ascorbic acid (4 mM) were incubated for 12 h at 37 ℃. Quercetin (100 μM) was used as a reference compound. After incubation, the reaction mixture was analyzed by electrophoresis in 10% SDS PAGE gel using a standard protocol, as mentioned by Sambrook et al[20]. The gel was stained with a brilliant blue R staining solution for 2 h and visualized under the Gel documentation unit (Bio-Rad Lab., CA, USA). Band area was calculated using ImageJ software. The result was expressed using the formula:

(Band area/Band area) × 100

Where, Band areais the band area of the control solution(without oxidizing system), and the Band areais the band area in the presence or absence of extracts.

2.6. In vitro toxicity assessment in human peripheral blood lymphocytes

2.6.1. Isolation of human peripheral blood lymphocytes

Human blood was obtained from 3 healthy male volunteers between 20 and 30 years of age (nonsmokers and not under any medications) after their consent. Lymphocytes were isolated from fresh blood, according to Bøyum[21], with slight modifications.

2.6.2. Trypan blue dye exclusion test

Effect on the viability of human lymphocyte cells by individual rhizome extract (C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga) at various concentrations (2.5 to 10 μg/mL) was studied by the trypan blue dye exclusion test[22]. Lymphocytes (1 × 10cells/mL) were incubated at 37 ℃ with different concentrations of the three plant extracts in RPMI-1640 media. After 3 h, cells were washed by centrifugation, and fresh media were added. The lymphocytes were stained with trypan blue dye (0.4% w/v). The numbers of viable and dead cells were scored under the light microscope with Neubauer’hemocytometer.

The viability of 3 × 100 randomly chosen cells was analyzed,averaged, and expressed as % of control using the following formula:Viability (% of control) = T/C × 100

Where T= Viable lymphocytes treated with different concentrations of extracts; C= Viable lymphocytes without treatment.

2.6.3. MTT reduction assay

Cytotoxicity of the extracts (C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga)at various concentrations (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) was evaluated using MTT assay, according to Mosmann[23]. Lymphocytes (1 ×10cells/mL) were incubated with the different concentrations of the three plant extracts (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) in RPMI-1640 media for 3 h at 37 ℃. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS by centrifugation at 2 000 rpm for 5 min. Lymphocytes were resuspended in RPMI-1640 media and seeded in a multi-well plate with each well containing 100 μL of cells. Ten μL of 0.5 mg/mL of MTT solution was added and maintained at 37 ℃. Then 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide was added and mixed thoroughly to dissolve the dark blue crystals. Formation of formazan was quantified on iMarkMicroplate Absorbance Reader (BIO-RAD, CA, USA) at 570 nm,with 630 nm as a reference wavelength. Results were expressed as the percentage (%) of viability with respect to control according to the following formula:

(A/A) × 100

Where A= Absorbance of the treated cells and A=Absorbance of the control cells.

2.7. Determination of intracellular ROS generation

Intracellular ROS generation upon exposure to rhizome extracts of C. amada, C. caesia, and A. galanga was quantitated using the fluorescent probe DCFH-DA in human blood lymphocytes according to Sinha et al[24]. The lymphocytes were incubated with rhizome extracts (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) at 37 ℃ for 3 h and were finally collected by centrifugation (1 000 rpm for 5 min). After that,the cells (1 × 10cells/mL) were resuspended in PBS with 25 μM DCFH-DA. The suspension was incubated in the dark for 30 min at 37 ℃. The samples were analyzed using a flow cytometer (FACS Aria Ⅲ with cell Sorter, BD, San Jose, CA, USA). Approximately 20 000 events were recorded from each sample, and processing was performed with FACS Diva software.

2.8. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential(Δψm MMP)

The effect of rhizome extracts of C. amada, C. caesia, and A.galanga on MMP of lymphocytes was assessed using Rhodamine 123 fluorescent dye following the method of Kim et al[25].Lymphocytes (1 × 10cells/mL) were incubated with the different concentrations of the rhizome extracts (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) in RPMI-1640 media for 3 h at 37 ℃. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS by centrifugation at 2 000 rpm for 5 min.Lymphocytes were suspended in 10 μM of Rhodamine 123 dye for 30 min at 37 ℃. Fluorescence was read using flow cytometry (BD,San Jose, CA, USA) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm.Results were expressed as the percentage (%) of MMP with respect to the control according to the following formula:

MMP (%) = (F/F) × 100

Where F= Fluorescence of the treated cells and F=Fluorescence of the control cells.

2.9. In vitro genotoxicity and anti-genotoxicity

The single-cell gel electrophoresis or comet assay was performed to assess the anti-genotoxicity of each of the extracts (C. amada, C.caesia, and A. galanga) at various concentrations (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL). For comet assay, the procedure of Singh et al.[26] was followed with minor modifications[24]. To study the anti-genotoxic effect of the individual extract, two different types of treatments were performed: (i) Lymphocytes were simultaneously exposed for 3 h to MMS (35 μM) and rhizome extracts at different concentrations; (ii)for HO, control cells or lymphocytes pretreated with the extracts for 3 h were embedded in agarose gel and either exposed to HO(250 μM) for 5 min on ice in the dark or processed without HOtreatment. Short-term HOtreatment at 0 ℃ was done to minimize the DNA repair process.

DNA damage was visualized under a fluorescence microscope(Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with appropriate filters. The tail DNA (%) was analyzed by the image analysis software Komet 5.5(Kinetic imaging, Andor Technology, Nottingham, UK).

2.10. Modulatory effect of C. amada on CP-induced DNA damage in vivo

2.10.1. Animals and treatments

Adult (5-6 weeks) Swiss albino male mice (23 ± 2) g, bred in the animal facility of the University of Calcutta, Kolkata, were maintained at a controlled temperature under alternating light and dark conditions. Standard food and drinking water were provided ad libitum.

The animals were divided into 6 groups of 5 mice each as follows:Vehicle control receiving 0.05% ethanol; CP group receiving a single intraperitoneal injection of CP (20 mg/kg body weight); two C. amada alone groups administered with 2.5 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg body weight of C. amada extracts, respectively; C. amada (2.5 mg/kg body weight) + CP (20 mg/kg body weight); C. amada (5 mg/kg of body weight) + CP (20 mg/kg body weight). Mice were treated with C. amada extracts for seven consecutive days and injected intraperitoneally with CP (20 mg/kg body weight) on the 7th day 18 h before sacrifice.

2.10.2. Antigenotoxicity

Antigenotoxic effects of C. amada (2.5 and 5 mg/kg body weight) against CP (20 mg/kg)-induced DNA damage in the bone marrow cells of Swiss albino mice were studied using alkaline comet assay following the method of Singh et al.[26] with minor modifications[24]. The lymphocytes of the genotoxicity test and MMS experiments were centrifuged and re-suspended in 1.0% low melting point agarose. A volume of 100 μL of the cells suspension was spread on a base layer (1% normal melting point agarose in water) on a microscope slide. When the agarose had solidified, the slides were transferred in a lysis mixture for 1 h at 4 ℃ to remove cellular proteins. Lysing (1 h at 4 ℃ in a Coplin jar) was followed by 20 min unwinding (1 mM EDTA, 300 mM NaOH) and 30 min electrophoresis at pH > 13. After electrophoresis, the slides were rinsed thrice with 400 mM Tris buffer, pH 7.5, to neutralize the excess alkali, air-dried at room temperature, and stored inboxes.Each slide was stained with 80 μL ethidium bromide (20 μg/mL) for 5 min, dipped in cold water to remove excess stain, and covered with a coverslip.

The comparative inhibition of tail DNA (%) was calculated by using following formula:100-[(z-x)/(y-x) × 100]

Where x= % tail DNA of the negative control; y=% tail DNA of CP group (20 mg/kg body weight), z=% tail DNA of CP+C. amada extract groups (2.5 and 5 mg/kg body weight).

Bone marrow cell viability of all the treatment conditions was checked using MTT reduction assay.

2.11. Chromatographic separation and identification of major constituents

2.11.1. HPLC analysis of curcuminoids

HPLC analysis was carried out using a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography apparatus equipped with an Agilent DAAD detector(Agilent, USA). The mobile phases were (A) 0.1% phosphoric acid and (B) acetonitrile with a linear gradient from 94% to 92.5% A for 4 min; stand at 92.5% for 3 min, from 92.5% to 10% A for 8 min, from 10% to 6% A for 5 min and 6% A for 5 min followed by washing with B and re-equilibration of the column for 5 min. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, and the injection volume was 20 μL.UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded on-line from 190 to 600 nm during the HPLC analysis. Reference standard curcumin (Sigma-Aldrich Co., USA) was used for identification and quantification.The DAAD detection was conducted at 425 nm. The compound was identified by comparing both retention time and UV-Vis spectrum with the reference standard. Percentage estimation of curcumin content was performed based on peak area (%) measurement.

2.11.2. GC/MS analysis of aromatic compounds

GC/MS analysis was performed on Agilent GC interfaced with a Quadrupole mass spectrometry using HP5 column with the oven temperature ranged from 70 ℃ to 260 ℃. The method was programmed at 5 ℃/minute ramping with an initial hold time of 1 min and a final hold time of 10 min. The carrier gas was He at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The injection port was set at 250 ℃. MS operating parameters include electron impact ionization at 70 eV with a mass range of 50-600 amu. Identification of compounds was accomplished by Kovats retention indices from literature and computer-aided search using the mass spectral library. Match and reverse match parameters for the identification of compounds set as >800 in the NIST mass spectral library. The percentage of the identified compound was computed from a total ion chromatogram.

2.12. Statistical analyses

All assays were carried out in triplicate for all the experiments. The results are expressed as mean and standard deviation values (mean ±SD) and were analyzed by Sigma Stat 3.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL,USA). Differences between means were determined by the analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests. The level of significance was established at P < 0.05 compared with the negative controls. Multiple Experiment Viewer (MEV 4.9.0) was used to construct a heat map and hierarchical tree for TPC and antioxidant assays and Minitabstatistical software to perform multivariate PCA.

2.13. Ethical statement

All experiments were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Calcutta (Approval No. #889/ac/06/IHEC, Date:18/07/2019), Kolkata, India. All the ethical issues strictly followed the guidelines of the ethical committee, University of Calcutta,Kolkata.

3. Results

3.1. TPC and antioxidant activity

The TPC of ethanolic extracts of A. galanga, C. caesia, and C.amada were ranged from (4.58 ± 0.33) to (65.91 ± 3.39) mg GAE/g of extracts, respectively (Figure 1A). The highest phenolic content was found in C. amada followed by C. caesia (35.23 ± 3.06) mg GAE/g of extract and A. galanga.

The antioxidant activities of the extracts were evaluated using multiple endpoints and demonstrated as a heat map in Figure 1A.The highest radical scavenging activity was observed in C. amada,which showed the highest colour reduction, followed by C. caesia.The ferric reducing values of the extracts ranged from (1.31 ± 0.02)to (43.08 ± 2.83) mg AAE/g of extract. C. amada showed the highest FRAP activity while the least activity was observed in A. galanga.The antioxidant potential of the extracts was further evaluated by ABTSradical scavenging assay and HRS assay. ABTS activity of the extracts ranged from (1.61 ± 0.30) to (34.21 ± 1.98) mg AAE/g extract. The highest ABTS activity was found in C. amada extract followed by C. caesia. In HRS assay, the ICvalues of the extracts ranged from (5.54 ± 0.27) to (18.06 ± 1.02) μg/mL. C. caesia showed a higher activity than C. amada. Furthermore, plant extracts showed varying lipid peroxidation inhibition activities with (46.45 ± 2.39)to (63.51 ± 5.96) mg AAE/g of extract. C. caesia and C. amada both showed almost similar inhibitory activity.

Heat map generated by MEV software clearly showed C. amada as the most potent antioxidant among the three extracts studied.The hierarchical tree placed TPC, FRAP, ABTS, and DPPH in one cluster, while HRS, and lipid peroxidation were placed in another. However, we observed proximal distance between TPC and other antioxidant assays (such as DPPH), indicating their close relationship while TPC as well as HRS and lipid peroxidation are placed at extreme ends, revealing distant relationship between them.

Considering the limitation of one statistical method, we further applied multivariate analysis tool-PCA to determine the correlation among variables (Figure 1B). The first component explained 99.4%of the variance, and the second component explained 0.6% of the variance. Together two components could explain 100% of the total variance. In agreement with hierarchical tree analysis, the results suggested that TPC as well as HRS and lipid peroxidation were distantly related, possibly indicative of the effect of other variables/phytochemicals class on this antioxidant property. Nevertheless,DPPH, FRAP, and ABTS were found to be highly correlated with TPC.

Plant extracts also significantly inhibited the oxidation of BSA restoring the band area of oxidized BSA similar to that of the control.A. galanga, C. amada, and C. caesia restored BSA band intensity significantly within the range of 72.04% to 77.46%, 77.74% to 88.11%, and 70.97% to 86.55% of the control, respectively (Figure 2).

3.2. In vitro cytotoxicity assessment in human peripheral blood lymphocytes

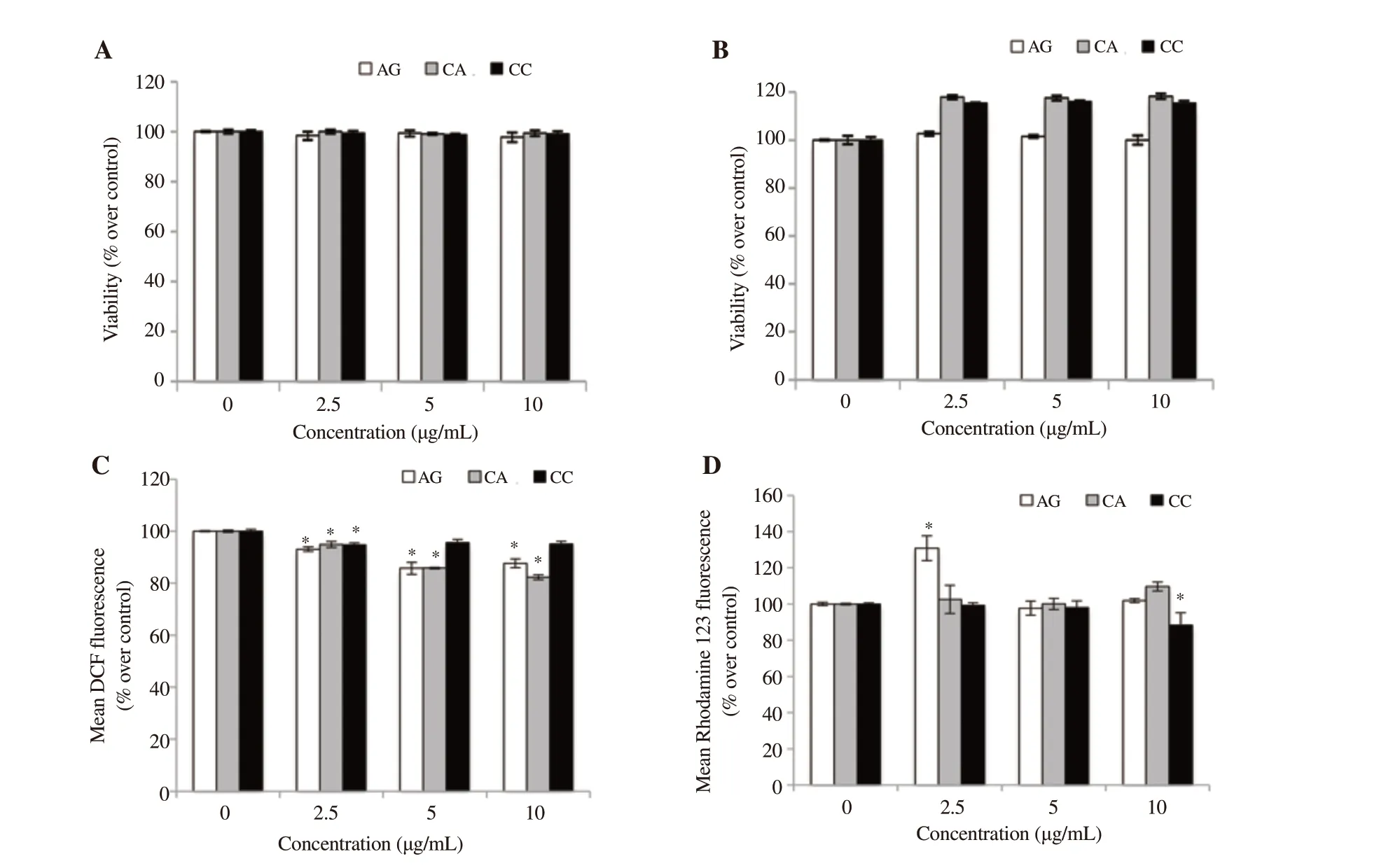

The cytotoxicity of the extracts on human lymphocytes was evaluated by the Trypan blue dye exclusion test and MTT assay. The Trypan blue dye exclusion test showed that the extracts at 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL exhibited >90% cell viability (Figure 3A).

MTT assay demonstrated that the extracts did not alter the cell viability of lymphocytes at tested concentrations (Figure 3B).

Figure 1. Antioxidant activities of Alpinia galanga extract (AG), Curcuma amada extract (CA), and Curcuma caesia extract (CC). (A) Heat map showing multiple endpoints of antioxidant activities of AG, CA, and CC; (B) Principal component analysis showing correlation among different parameters of antioxidant activities. TPC: total phenolic content, FRAP: ferric reducing antioxidant power assay, DPPH: 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl assay, ABTS: 2,2'-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) assay, LPO: protection against lipid peroxidation assay, HRS: hydroxyl radical scavenging assay.

3.3. Effect of plant extracts on intracellular ROS generation

The effect of plant extracts on the generation of ROS in human lymphocytes was assessed by flow cytometry using DCFDA dye.The plant extracts at all tested concentrations were found to be safe and did not generate any basal ROS. C. amada and A. galanga at all concentrations and C. caesia at 2.5 μg/mL significantly reduced basal ROS in lymphocytes (Figure 3C).

3.4. Effect of plant extracts on MMP

The effect of the extracts on MMP of lymphocytes was evaluated using fluorescent dye Rhodamine 123 by a flow cytometer. The results indicated no significant decrease in fluorescence intensity at all tested concentrations of the extracts except 10 μg/mL concentration of C. caesia (Figure 3D).

3.5. In vitro genotoxicity and anti-genotoxicity

Single-cell gel electrophoresis (comet assay) was performed to observe the genotoxic and anti-genotoxic potential of the extracts in human lymphocytes. The result showed that the extracts were nongenotoxic per se at all tested concentrations and were able to reduce DNA damages induced by MMS and HO(Figure 4A-C).

Figure 2. Inhibitory effect of plant extracts (A: AG, B: CA, C: CC) on protein oxidation. BSA was oxidized as described in Methods and stained with a brilliant blue R staining solution. Values are expressed as mean ± SD, * statistically significant difference from control (P < 0.05). AA: Ascorbic acid, Que: Quercetin.

Figure 3. In vitro toxicity assessment of AG, CA, and CC in human lymphocytes. (A) Trypan blue dye exclusion test, (B) MTT assay, (C) Bar diagrams showing quantification of DCF fluorescence at different concentrations of rhizome extracts, (D) Bar diagrams showing quantification of Rhodamine 123 fluorescence. Values are expressed as mean ± SD, *statistically significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

The extracts A. galanga (5 μg/mL) and C. amada (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL) significantly inhibited MMS-induced DNA damage in human lymphocytes. On the other hand, HO-induced DNA strand breaks were significantly inhibited by A. galanga (2.5 μg/mL), C.amada (2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL), and C. caesia (5 and 10 μg/mL).Comparative analysis (Figure 4D) showed that C. amada was most effective among all three extracts and showed 51.6% and 64.41%inhibition against MMS- and HO-induced DNA damage at 10 μg/mL, respectively.

3.6. Modulatory effect of CA on CP-induced DNA damage in vivo

The result showed that CP caused remarkable DNA damage.However, C. amada conferred protection against CP-induced DNA damage in bone marrow cells and DNA damage was significantly inhibited at 2.5 mg/kg of C. amada (Table 1). Besides, all treatment conditions were non-toxic to the cells (viability >90%), as shown by the MTT cytotoxicity assay.

3.7. Identification of major constituents by HPLC and GCMS analyses

The HPLC analysis identified curcumin and demethoxycurcumin as principal constituents in C. amada (Figure 5A and B). The GC-MS analysis identified caryophyllene, a sesquiterpene, as the principal constituent in the hexane fraction of C. amada (Figure 5C & D and Table 2).

Table 1. % tail DNA and % inhibition of cyclophosphamide-induced DNA damage in mouse bone marrow cells by Curcuma amada.

Table 2. List of compounds in hexane fraction of Curcuma amada ethanolic extract by GC-MS analysis.

4. Discussion

Antioxidant properties of plant extracts have been extensively exploited for their medicinal potentials for ages. The family Zingiberaceae constitutes a large number of aromatic members with significant antioxidant attributes. Plants such as mango ginger (C.amada), black turmeric (C. caesia), and galanga (A. galanga) are well known as traditional healers against various health issues and consumed globally as spices, especially in the southern part of Asia.In the recent era, people are more exposed to multiple mutagens and carcinogens through the environment, foods, or medicines. These compounds are capable of causing severe DNA damage, leading to several diseases, including cancer. Although literature established a link between antioxidant and medicinal properties of Zingiberaceous plants, anti-genotoxic data on such compounds are scarce, especially in the animal system.

In this background, our preliminary study was attempted to screen the antioxidant properties of ethanolic extracts of C. amada,C. caesia, and A. galanga rhizomes. The antioxidant mechanism in biological systems differs significantly and may include the pathways such as chelating of transition metal ions, quenching of free radicals to terminate the radical chain reaction, reducing the oxidants, or stimulating the antioxidant enzyme activities[27]. Given this complexity of antioxidant mechanisms prevailing throughout the plants, we considered four cell-free in vitro antioxidant assays,namely DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and HRS in the present study. The data from these assays demonstrated the ability of the extracts to donate electrons to reactive radicals, converting them into more stable and non-reactive species. The members of Zingiberaceae are well documented for their significant antioxidant properties in agreement with our work[28,29].

Interestingly, except HRS assay, C. amada was found to be the most potent antioxidant in all other assays. Siddaraju and Dharmesh reported antioxidant activities of free and bound phenolic constituents of C. amada rhizome in terms of DPPH radical scavenging and reducing potentials[7]. Although all other extracts showed good antioxidant potentials, the weak activity of A. galanga was evident in our study. An earlier report by Mahae and Chaiseri[30]indicated that the extraction with a high percentage of ethanol (95%)might lead to the weak antioxidant activity of A. galanga rhizome.

The hydroxyl radical (OH) is an extremely reactive free radical in biological systems and has been implicated as a highly damaging species in free radical pathology. This phenomenon was exploited in our study in the form of Fenton’s reaction (to generate OHradicals)to assess the protective activity of the extracts using biomolecules,i.e., lipid and protein substrates. Plant extracts have been reported to have significant protective activities against Fenton’s reaction generated hydroxyl agent[31,32]. All three extracts had shown considerable radical scavenging properties in our study as well.

Figure 4. Anti-genotoxic potential of AG, CA and CC extracts (A-C) against DNA damage induced by methyl methanesulfonate (MMS, 35 μM) and H2O2 (250 μM) in human lymphocytes by comet assay. (D) Comparative analysis of DNA damage inhibition (%) by rhizome extracts. Values are expressed as mean ± SD,*statistically significant difference from control, P < 0.05.

Figure 5. Phytochemical analysis of CA extract. HPLC chromatogram of (A) curcuminoid reference standard: curcumin [1] and demethoxycurcumin [2], (B)CA showing curcumin [1] and demethoxycurcumin [2] at the wavelength 425 nm, (C) total ion chromatogram of hexane fraction of CA by GC-MS analysis, (D)mass spectral comparison of sample peak caryophyllene as one of the major components of CA (As per National Institute of Standards and Technology Mass Spectral Library-NIST).

Plant extracts are the complex mixtures of secondary metabolites,phenolic compounds among those receiving unique attraction due to their prominent antioxidant potentials. Various authors have extensively studied the nature of phenolic compounds in different plant extracts. In Zingiberaceous members, the direct correlation between their phenolic constituent and antioxidant properties has been established by researchers. Krishnaraj et al.[33] investigated the phenol content and antioxidant activity of two non-conventional Curcuma sp., namely, C. caesia and C. amada. Policegoudra et al.[8]reported significant phenolic constituent in Curcuma sp. In line with these findings, we found that C. amada is rich in phenolics and also the highest in content among the studied three extracts.

Multivariate data analysis in the form of PCA has been utilized by peer investigators to understand the underlying correlation among different variables, e.g., antioxidant parameters in our case. Wong et al.[34] established an overall correlation among different antioxidant properties and total polyphenol content, taking 25 edible plants into account. Our study comprising three alcoholic extracts revealed statistical correlations among the TPC, FRAP, DPPH, and ABTS variables, clearly showing the influence of phenolics in determining the antioxidant potentials of plants. Interestingly, we found HRS and lipid peroxidation are not correlated with the phenolic constituent,indicating the probable influence of a different class of secondary metabolites other than phenols. A similar observation was also found while the hierarchical clustering method was applied.

The biological effect of plant extracts is often contradictory. Various literature previously indicated that extract might pose a significant cytotoxic effect. Hence, it is imperative to assess the cytotoxicity of the plant extracts. In the preliminary study, the concentrations of three extracts are selected as 2.5, 5, and 10 μg/mL based on the trypan blue exclusion test and MTT assay. Mitochondrial activity is closely associated with cellular health. Further, crude extracts at toxic concentrations impart oxidative stress to the cellular system through the mechanism of oxidative stress. In the current study, the selected concentrations of the extract did not exert any cytotoxic effect on human lymphocytes, as evident by flow cytometry-based MMP and DCFH-DA assays.

MMS is extensively used as an experimental model to act as a classical DNA damaging agent[35]. It is a monofunctional alkylating compound capable of breaking the DNA strands directly by electrophilic attack[36]. The mechanism underlying the protective effect against MMS-induced DNA damages by cashew nut extract in V79 cells was attributed to the desmutagenic property of the extract[37]. Desmutagens inactivate mutagens or their precursors irreversibly by direct chemical interaction. A similar co-treatment protocol resulted in significant inhibition of MMS-induced DNA lesions in the human lymphocyte cells in vitro, indicating the desmutagenic effect of the extracts in the current study. HOis a member of the ROS family that mimics the radiation like effect by promoting DNA strand break[38]. In several scientific studies, HOwas used as a positive compound for inducing cellular oxidative stress to elucidate the anti-genotoxic properties of extracts and essential oils[24]. While all extracts were capable of significantly inhibiting the DNA damage induced by both MMS and HO; all three concentrations of C. amada showed the highest protective activity against those genotoxins.

In recent years, the goal of pharmaceutical research has focused on the concept of the application of in vitro-in vivo correlation[39].CP is an alkylating agent extensively used as a chemotherapeutic drug. Cytochrome P-450 mixed oxygenase system metabolically activates this drug and produces metabolite acrolein in this process.This compound is known to induce oxidative stress causing DNA strand excision in healthy cells[40]. As C. amada was found to be the most potent antioxidant and anti-genotoxic agent in our study, it was further selected to perform in vivo study against CP. The extract offered protection towards the CP-induced DNA damage in bone marrow cells of Swiss albino mice, which impart the antioxidant mechanism.

Chemically, extracts are the complex mixtures of numerous compounds and exert their biological functions such as antioxidant and anti-genotoxic activities either separately or synergistically.The rhizome of C. amada was reported to contain considerable amounts of phenolic acids and terpenoids[8]. In the present study,the high contents of total polyphenol and flavonoids were estimated in agreement with the previous findings. While investigating the phytochemical compositions of C. amada, significant content of curcuminoids (curcumin and methoxy curcumin) was detected by HPLC. Curcuminoids are the natural class of phenols, which include curcumin and its derivatives. Our results were in agreement with the previous finding, which declared curcuminoid as one of the major components in the extract of C. amada rhizome[41]. In addition to that, the substantial presence of terpenoids was also detected in C.amada. Phytochemicals chiefly including phenolics and terpenoids are proposed as potential antioxidants and thereby, in part, contribute to the anti-genotoxic property of a plant. Antioxidants chemically are classified into two types, namely phenolics and β diketones.Phenolics and β diketones act as hydrogen and electron donors,respectively. Being a unique conjugated structure comprising phenols and β diketone groups, curcumin and its derivatives are potent antioxidants with excellent radical scavenging and antilipid peroxidation capacities[42]. A promising antioxidant potential of C. amada found in this study was in support of the finding of Abrahams et al.[43] who exhibited substantial antioxidant activities of curcuminoids. The possible influence of anti-genotoxic property of C. amada in our study might be attributed to the strong anti-genotxic potential of curcumin[44]. A study by Nagavekar and Singhal[41]indicated that additional compounds contributed to the antioxidant capacities of tropical ginger extracts and curcuminoid. Terpenoids detected during this investigation might support this assertion. These compounds are the major constituents of plant essential oils and are reported to possess significant antioxidant and anti-genotoxic properties[24]. The presence of a high amount of terpenoids might be correlated with the inhibitory activities of lipid peroxidation and HRS, which showed no correlation with the phenolic constituents of the extracts in statistical analysis. However, in the case of the biological properties of C. amada, the participation of other phenolic compounds could not be ruled out.In conclusion, the present study investigates the antioxidant activity and anti-genotoxic potential of A. galanga, C. amada, and C. caesia ethanolic extracts. Results showed that all three extracts did have antioxidant properties as revealed by in vitro antioxidant and antigenotoxic assays. However, C. amada was found to be the most potent antioxidant when compared with the other two plant extracts.Furthermore, in the in vivo study, C. amada could protect CP-induced DNA damages in bone marrow cells of Swiss albino mice, which might be due to the phytochemicals present in the mango ginger as determined by HPLC and GC-MS. However, as this is a preliminary report based on a few selected parameters, further investigations with extensive parameters are warranted.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Prof. M. Sabu of the University of Calicut, Calicut for providing us A. galanga rhizome. We extend our gratitude to Dr.Mousumi Poddar Sarkar of University of Calcutta, Kolkata, for her expert guidance in GC-MS analysis.

Authors’ contributions

AN designed the study, performed the experiments and prepared the manuscript. RB and PG performed parts of the experiments together with AN, and helped in data analysis and preparing the manuscript.AM and MB corrected the manuscript, supervised the experiments and provided valuable suggestions to improve the study.杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Anti-viral and anti-inflammatory effects of kaempferol and quercetin and COVID-2019: A scoping review

- Valencene-rich fraction from Vetiveria zizanioides exerts immunostimulatory effects in vitro and in mice

- Bitter gourd extract improves glucose homeostasis and lipid profile via enhancing insulin signaling in the liver and skeletal muscles of diabetic rats

- Cytotoxic effects of Thai noni juice product ethanolic extracts against cholangiocarcinoma cell lines