“虚空间”还是“宇宙另一方”:音乐歌单因疫情而变化

2021-07-06司马勤

司马勤

要是平常日子的话,遇到这个问题我一点都不会觉得奇怪。每当好友栩然发消息给我,让我就她工作时听什么音乐给点建议时,我就会寻找点这些日子的新发现跟她分享。一直以来,我都认为音乐评论这个范畴本质上只不过是为朋友们特别炮制的歌曲混音合集的一种文字形式的呈现罢了。说真的,即使现在我们讨论的是推荐播放歌单,但筛选原则都是一样的。

对于我的推荐,栩然的回复通常都是“不可以啊,如果我听这首乐曲,就会什么都做不了……”或者“在办公室里听这类音乐太诡异了。好像有人在身后悄悄逼近我一样”。(她在金融公司工作,会产生那种咄咄迫人的疑虑并非空穴来风……)她以往对我推荐的那些跨流派的实验性作品的反应都是:“你是认真的吗?”

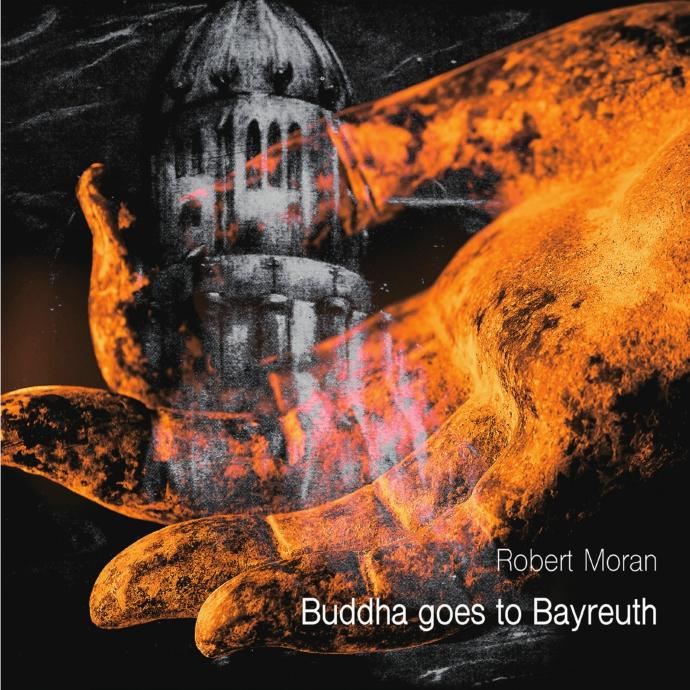

但我发现她偶尔洞悉音乐的直觉以及评论的角度,要比受过训练的专业乐评人更尖锐。这次,我在这个特殊的“大礼包”里打包了什么给她呢?首先,一首打击乐协奏曲,名为《打雀英雄传之又见东风》,独奏家运用的打击乐器包括一副麻将牌。还有,乔纳森·凯恩(Jonathan Kane)与戴夫·索迪埃(Dave Soldier)两位音乐人合作的新专辑,那令我想起多年前中提琴演奏家约翰·凯勒(John Cale)同期参与摇滚乐手路·瑞德(Lou Reed)组建的地下丝绒乐队(Velvet Underground),以及极简主义者拉蒙特·杨(La Monte Young)的前卫音乐。最后,我在歌单中加了罗伯特·莫兰(Robert Moran)的《佛祖到拜罗伊特去》(Buddha Goes to Bayreuth)。瓦格纳生前曾构思想要写一部以佛学为主题的歌剧,可惜没有实现。莫兰用了《易经》中的占卜法选出《帕西法尔》歌剧中一些和声,然后再套上佛经经文。我们行内人用“高概念”(high concept)来形容这类艺术行为。

够怪诞了吗?说实话,如果栩然想听大众化的乐曲,她大可以坚持使用流媒体音乐服务平台“声田”(Spotify)。

正如我刚才暗示过的,今年一点都不寻常。在过去12个月里,大家很少有机会听得到现场演出。这个状况让我们有充分时间来深思自身与艺术的关系。对我来说,高居问题榜首位的就是一直令我感到矛盾的录音制品。曾来过我家的人肯定都会取笑我,因为他们进门后直接映入眼帘的就是一叠又一叠的CD碟。多年来,我曾担任《留声机》大奖(Gramophone Awards)的评审,这是英语区古典音乐圈中最受推崇的獎项。曾几何时,我特意飞到伦敦去,换上礼服参加星光熠熠的颁奖典礼。然而回首一望,我也不再怀念那些日子了。

朋友问我为什么会撰写录音评论,我通常回答说,光整天坐在家里听录音不像是个“成熟”的维持生计的工作。当然,事实不仅如此。从小我就演奏乐器,还参加合唱团,但在今天的社会里提及这些活动会显得古板而与时代脱节,这种认知令我毛骨悚然。自从黑胶唱片(LP record)发明之后,音乐就再不是你参与创造的了,而是你双手可以抓住的实物。现在我们已经进入了互联网下载的年代,人与音乐的关系甚至连实物的联系也消失了。对于非专业人士来说,演奏和唱歌这些本来属于人类的主动行为差不多也快销声匿迹了。

对我来讲,情况显得更糟糕。商品化的社会通常引致物资泛滥饱和,好好的产品因为随处可见就变得一钱不值。我对日本语中“间”(日语发音ma,与汉语中的“留白”相似)这个概念特别感兴趣——英语翻译通常是“虚空间”(negative space)——即可感知的内容之所以有意义,主要是因为它周围的空白。从音乐的角度来说的话,即音乐的意义来自它出现之前的静寂以及乐曲奏罢之后的静寂。

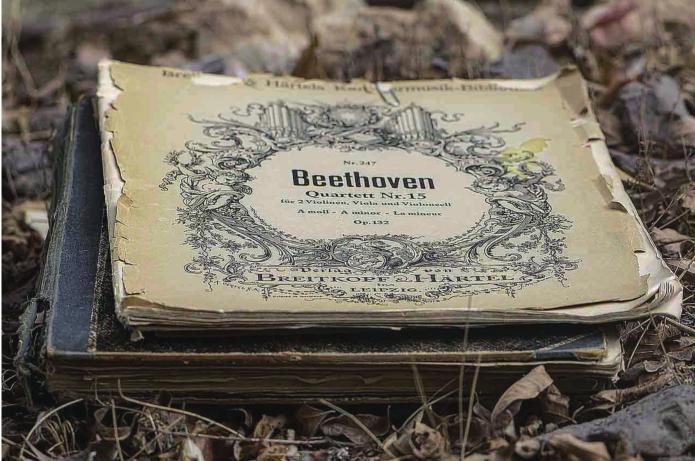

你想找出古典音乐中宣扬这种哲学的代表人物吗?很简单,我们就来看看那位出生在波恩的“乐圣”吧。大部分作曲家并不单刀直入,但贝多芬从一开始就明白静寂的重要性。他的第五交响曲的头5秒是西方古典音乐历史上最著名的开场白。反过来,如果你听听他《第九交响曲》最后的30秒,也可以领略到那是所有传统古典交响曲中最完美之作。这位伟大的作曲家懂得如何真正掌控乐曲的结尾。

但是,哲学理论中正反两面的论点,往往都是不相伯仲。我还记得有一次排练巴赫的赞歌,指挥听到我们过分强调乐句的开头,令他的耳朵受不了,连面部肌肉都开始抽搐。他停了一阵,整理思绪,然后抬起头教导合唱队:“想象一下,在宇宙的另一边,有人正在演唱这首赋格曲,而你们准备加入其中。”

几百年来,音乐价值观就像个钟摆一样徘徊于两个极端之间,直到20世纪才实现了和平共处。音乐厅、歌剧院或任何可以举行现场演出的场地都是“间”哲学最自然、最有归属的地方。录音、点播流媒体与其他任何方式的媒体都属于“宇宙另一方”那个派系。数十年来,你可以每天早上在床头柜打开收音机,在工作的地方听到广播,在任何公共场合也听得到音乐。因此,一整天都有无间断的音乐声轨的存在。

想当年,主动聆听(与周围环绕充斥的背景音乐刚好相反)必须要依赖有限的资源,而这些资源的量度以时间与空间为主。我还记得有一年的圣诞节,老朋友弗兰克送了一份包装精美的礼物给我,就是1968年《艾灵顿公爵第二场神圣音乐会》(Duke Ellingtons Second Sacred Concert)的黑胶唱片。“只值3美元,”他当年的夫人轻蔑地加了一句。弗兰克立刻反驳道,“这不是多少钱的问题!我足足花了6个月的时间才找到这张唱片!”

时至今日,我肯定栩然即便身处香港,也只需在敲击几下电脑键盘就可以寻到艾灵顿公爵第二场神圣音乐会的音频资料。差不多从她孩提时代到现在为止,任何关于音乐历史的资讯,想要搜索,一上网就垂手可得,通常还都是免费的。可前提是,她必须知道有那些作品的存在。说真的,音乐下载实在很难全部打包。

***

這一段日子,劳德维克·奥登司(Lou Ottens,1926~2021,发明盒式磁带的工程师)的粉丝悲伤不已。这位伟人3月初逝世,享年94岁。诚然,很多人未必知道他的名字,但他毕生的成就,在世界各地——从柏林到波士顿再到北京——都带来极大的回响。1960年代初期,奥登司为录音科技引进革命性的突破:他找到一个有效的方法,把笨拙的盘式磁带置入容易携带的小塑料盒之内。

大家都留意到这里一丝的反讽。当年没有人喜欢盒式磁带(或称卡式磁带)。盒式磁带的音响效果远逊于黑胶唱片,且磁带也保存不久。如果你把盒式磁带摆在任何有磁性的物体附近,磁带就会失效,上面的东西会永远消失。大概四分之一个世纪后,当CD唱片开始流行,盒式磁带因而淘汰消失,没有人对此感到惋惜。

这个状况所代表的不仅仅是关于盒式磁带,而是它当年代表的社会形态:成本更低、携带更轻便(尤其是后期磁带录音机的体积变得越来越小),而且最重要的是,录音过程简单直接。突然间,音乐爱好者们不用再被唱片出版行业牵住鼻子走。只要手中有空白的盒式磁带,你就可以决定你要听的音乐内容。

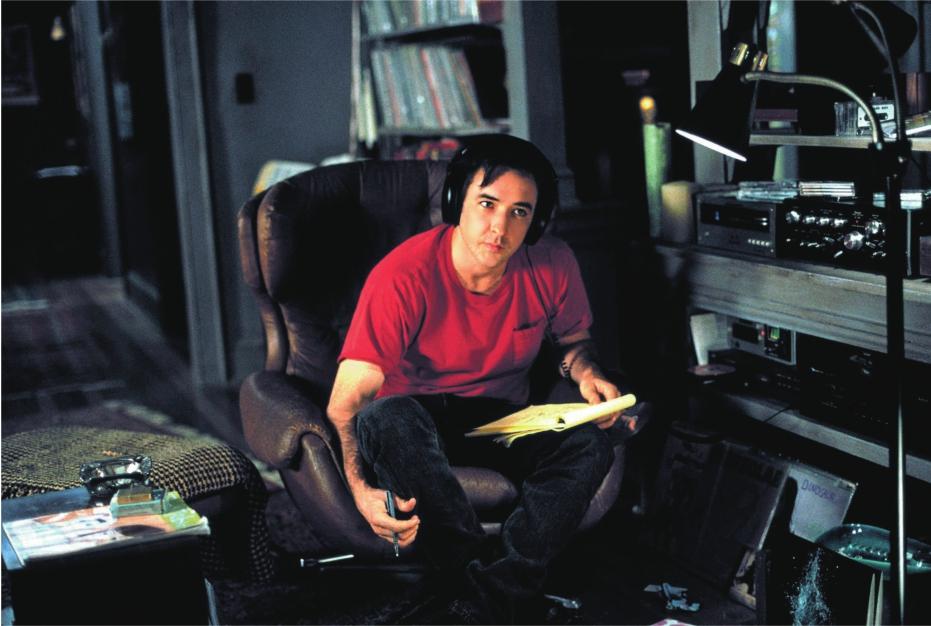

盒式磁带的兴起也许未必对鼓励人们自己表演音乐起到多大的作用,但这个轻便的科技发明却让一代的音乐爱好者成为活跃的“音乐策展人”。你可以拼凑一个围绕特别主题的歌曲或乐章——对了,就是所谓的“歌曲合集混音带”(mixtape)——宣扬你的品位,跟朋友讨论彼此的爱好,甚至诱惑情人。小说家尼克·霍恩比(Nick Hornby)在他的处女作《失恋流行榜》(High Fidelity)中编纂了“混音带”美学。小说的主人公描述自己为新认识的目标情人付出“很多个小时,把盒式磁带录好……就像写信一样——写下来了又删掉又再构想,然后从头来过”。

同样,就像写信一样,即使铅笔被电脑键盘所取代,我们似乎也保持了原则的完整性。自从可擦写模式的CD进入市场,我就再不怀念盒式磁带。今时今日,我也勉强接受了播放清单这个概念,因为它的确使用方便。要把CD邮寄到香港,速度慢得无法想象。

***

起初,栩然找我是因为她太久没有机会进入剧场或艺术中心看歌剧现场演出。我,或者任何人,都无法带她去看歌剧,所以她唯有满足于看莫兰解构《帕西法尔》的那部作品。不知何故,这个选择又显得很合适。正因这一年来,整个音乐世界基本上就像是崩溃了,再次拼贴起来的时候又显得纷乱如麻。

让我们静下来梳理一下来龙去脉吧:在声名狼藉的混音磁带与互联网音乐播放清单之间,音乐爱好者们有机会运用自己的“策划自由”(在尊重法律和版权,还有其他事项的基础上),但这也意味着唱片公司与演奏家的收入大减。因为盗版的影响以及流媒体平台付出的糟糕透顶的费用,唱片公司与流媒体平台都怂恿音乐家们不要指望录音可以带来收入。录音只能被视为推广工具,或是吸引粉丝买票看现场演出的促销机制。

有一段时间里,每个人似乎都很幸福——不是说完全快乐,而是那段有现场演出的日子至少还可以正常地工作。在过去一年里,现场演出全被取消,或恢复了又被叫停,录音业因此再次复兴——艺术家在录音棚里对着话筒就可以表演了。在世界各地,音乐爱好者们对新事物有着更大的渴望,他们可以在自己的家中尽情享受和探索。

疫情期间的日志记录者们经常歌颂音乐如何让他们的生活延续下去。然而,并非所有的音乐都表现得这么好。失败者?贝多芬就是其中之一。在过去的演出季中,贝多芬本应是全球最受公众追捧的作曲家,因为2020年是他诞辰250周年。然而有趣的是,有关他的现场音乐演出数量,亚洲要比他老家德国与奥地利多得多。

但是我们应该考虑到,问题不只是现场演出数量少那么简单。相反,世界的审美平衡似乎完全转向了另一个方向。夺得压倒性胜利的大赢家是约翰·塞巴斯蒂安·巴赫——不仅是那些注定极受欢迎的圣诞节复活节,连因为疫情公众士气最低潮的时候,巴赫那些令人深思的大提琴或键盘独奏作品,也给数以百万计的听众带来慰藉。大家从音乐找到安慰,也因观赏独奏家受到疫情限制仍然可以奏出美妙音乐而备受鼓舞。

是因为巴赫自己也经历过类似的灾难吗?1723年,巴赫撰写的康塔塔25号,正是马赛因为疫情导致10万人死亡的第二年。这部康塔塔的歌词没有署名,描述的情景包括“整个世界变成一个医院”以及“孩子因病而躺在床上”。的确,巴赫的同理心是非同寻常的,但我猜今天的听众经历了过去一年后必定也会感同身受。

现在可以点播的流媒体太多了,音乐确实总是在宇宙的某个地方响起。我想起大学时代那位指挥合唱的教授,对这段记忆忍俊不禁,突然间他那充满委屈不知怎么就变成了巴赫本人的形象——他就在“宇宙的某一边”,正在弹奏羽管键琴,并期待着我们加入其中。

Normally Id think nothing of it. When someone like my friend Bella asks me to send her something to listen to, Id immediately start sifting through some recent discoveries. Ive always thought of music criticism as little more than a literary form of making mixtapes for friends. Even if its all playlists these days, the principle is still the same.

Bellas responses often run along the lines of “Nope, cant listen to this and get anything else done…” Or,“Too eerie to listen to at the office. Felt like someone was always creeping up on me.” (She works at an investment bank, so that part may actually be true...) Her usual reaction to experimental cross-genre stuff is, “Seriously?”

But sometimes she nails something that even a trained professional would find hard to describe. So what did I send in this particular gift basket? First, a percussion concerto entitled Its the East Wind Again, where one of the solo instruments happens to be a set of mahjong tiles. Then a duo album by Jonathan Kane and Dave Soldier harking back to the days when violist John Cale could alternate between rocker Lou Reed in the Velvet Underground and avant-garde minimalist La Monte Young without batting an eye. And finally, Robert Morans Buddha Goes to Bayreuth, imagining the Buddhist opera that Wagner contemplated (but never wrote) by setting Buddhist mantras to random chords from Parsifal rearranged by consulting the I Ching. This is what we professionals call “high concept.”

Was this too weird? Really, if Bella wanted normal stuff she wouldve stuck with Spotify.

As I hinted earlier, though, this year is hardly normal. Not having much live music in the past 12 months has given us all plenty of time to ponder our relationship to the art, and high in my own thoughts has been my long-held ambivalence toward recordings. This is probably laughable to anyone whos stumbled over the stacks of CDs in my apartment. For years, I was on the jury for the Gramophone Awards, the most prestigious honors for classical recordings in the English-speaking world. I even flew to London and got dressed up for the ceremonies a few times. But I really dont miss it.

When people ask, I usually say that sitting around the house all day listening to recordings didnt seem to be a terribly grown-up way to make a living. But it was actually more than that. Having grown up singing and playing music, part of me bristled at how quaint this now seems. Ever since the LP, music was no longer something that you did but something that you held. In the age of downloads, most people have no physical relationship to music at all. For the nonprofessional, music has been largely erased as an active human experience.

The more I thought about it, the worse it seemed. Commodification generally leads to abundance, and nothing cheapens a commodity like ubiquity. Ive always been fascinated by the Japanese concept of ma—or as we call it in English, “negative space”—the idea that that perceptible content has meaning mostly because of the emptiness around it. In musical terms, that means that music means something only when it emerges from and retreats into total silence.

Anyone searching for a poster boy for this way of thought need look no further than the bard of Bonn. Many composers take a while to get the point; Beethoven bounds right from the starting gate. The first five seconds of his Fifth Symphony is the most famous opening in western music. Conversely, listen to the last 30 seconds of his Ninth, which is practically the last word in the whole symphonic tradition. Now theres a guy who could write an ending!

But as with so many philosophies, the converse can also be true. I remember rehearsing a Bach motet when our conductor winced with distaste at the inappropriately aggressive attacks in our opening phrases. He paused for a moment to collect his thoughts, then looked up. “Just imagine that this fugue is always unfolding somewhere in the universe,” he said. “Youre only joining it now.”

For hundreds of years, musical values have swerved between these two extremes, reaching a peaceful coexistence only during the 20th century. Concert halls, opera houses or any other venues for live performance are the natural home of the ma school. Recordings, on-demand streams and pretty much any other form of media make up the “somewhere in the universe”school. For decades, you could move through your day from the radio on your nightstand to the workspace and any public space inbetween to a constant musical soundtrack.

Active listening, though—as opposed to omnipresent background stuff—was restrained by limited resources, mostly measured in space and time. I fondly remember one Christmas when my friend Frank presented me with a gift-wrapped LP of Duke Ellingtons Second Sacred Concert from 1968.“It only cost three dollars,” his then-wife sniffed dismissively. Frank snapped back, “Its not about the money! Its about the six months it took to find it.”

Today, even though she lives in Hong Kong, Bella couldve found Ellingtons Sacred Concerts in a couple of keystrokes. For most of her life, the entire spectrum of music history has been readily available on the internet, often for free. But shed have to know that its out there. And really, a music download is hard to wrap.

***

This was a sad month for fans of Lou Ottens, who died in early March at the age of 94. Admittedly, few remembered him by name, but its safe to say that his work was known from Berlin to Boston to Beijing. Back in the early 1960s, Ottens revolutionized the recording industry by figuring out how to fit clumsy reel-to-reel tape into a portable plastic container.

We should all note the irony here. Despite all the nostalgic mourning, no one really liked the cassette tape. The audio quality was notably inferior to an LP, nor did it last as long. If you put a cassette near anything magnetic, the content would disappear forever. After CDs came out a quarter-century later, the cassette basically disappeared and nobody noticed.

So it was always less about the cassette itself than what it represented: lower cost, supreme portability(especially as players got smaller), and above all, ease of recording. Suddenly, music lovers were no longer so tethered to the whims of the recording industry. Armed with blank tapes, they could determine the content.

The rise of the cassette may not have done much to encourage people to perform music themselves, but it turned a generation of music fans into active curators. By fitting specific songs or pieces around certain themes—yes, the notorious mixtape—people could proudly proclaim their tastes, argue with friends, seduce lovers. Author Nick Hornby practically codified the esthetics in his first novel High Fidelity.“I spent hours putting that cassette together,” says Hornbys protagonist, describing a tape for a new love interest. “[its] like writing a letter—theres a lot of erasing and rethinking and starting again.”

And also like writing a letter, we seem to have kept the principles intact even after the pencil gave way to the computer. I havent missed cassettes since CDs became rewritable, and thanks to online convenience I even grudgingly accept the idea of playlists. Mailing a CD to Hong Kong would take forever.

***

Initially, Bella had asked me for music because she missed seeing live opera. Since there was nothing I—or anyone else—could take her to, shes going to have to settle for Morans deconstructed Parsifal. Somehow it seemed appropriate, since the whole music world essentially imploded this year and pulled itself back together more orless at random.

Lets ponder a bit about where we came from: somewhere between the infamous mixtape and the internet playlist, greater curatorial freedom among music fans (legal and otherwise) has meant less income for record labels and musicians. Thanks to piracy and generally abysmal payment from streaming platforms, musicians have recently been strongly urged—not least by record labels and streaming services—to treat recordings as a loss leader, a promotional mechanism to lure fans to live concerts.

For a while, everyone seemed to be—well, not exactly happy, but at least functional. At least while there were still concerts. For the past year now, as live performances have either sputtered or ground to a halt, recordings have once again been in ascendance. In the studio, artists only need to get close to the microphone. Around the world, music lovers had an even greater hunger for new things they could enjoy and explore in the privacy of their own homes.

Diarists during this years pandemic have frequently waxed poetic about how music has sustained them. Not all music has fared so well, however. The losers? Well, Beethoven, for one. During the past season, Beethoven was supposed to be feted publicly across the world in honor of his 250th birthday. Funnily enough, his music received more live performances in Asia than it did his own homelands of Germany and Austria.

But it wasnt just the lack of live performances. Rather, the esthetic balance of the world seemed to shift in the other direction entirely. The winner, by what appears to be a landslide, is Johann Sebastian Bach—not just during Christmas and Easter, when his popularity is a given, but also during the darkest points of the year, when the more contemplative solo works for cello or keyboard gave uplift to millions of people, whether from the music itself or a heartening example of what one person can achieve in confinement.

Is it because Bach went through similar experiences himself? His Cantata No. 25 from 1723—one year after the city of Marseille suffered 100,000 deaths from the plague—is entitled “There is nothing healthy in my body,” with an opening tenor recitative declaring “the whole world is nothing but a hospital”where “people and even children in their cradles lay in pain and sickness.” Indeed, Bachs empathy was extraordinary, but the newfound resonance in his music says just as much about us as listeners today.

With so much streaming on demand available these days, music is indeed always going on somewhere in the universe. Recently, as I was laughing at the memory of my collage choral conductor, his aggrieved face began morphing into a vision of Bach himself. There he sat, furiously playing his fugues at the keyboard, waiting for us to join him.