印太交汇区海洋软体动物生物多样性研究进展*

2021-03-30张均龙张树乾焦英毅

张均龙 张树乾 焦英毅

印太交汇区海洋软体动物生物多样性研究进展*

张均龙1, 2张树乾1, 2焦英毅1, 3

(1. 中国科学院海洋研究所 青岛 266071; 2. 中国科学院海洋大科学中心 青岛 266071; 3. 中国科学院大学 北京 100049)

印太交汇区珊瑚礁大三角是全球海洋生物多样性最高的区域, 孕育了印度-西太平洋海域接近60%的软体动物种类, 同时也有很高比例的特有物种。该海域是全球软体动物生物多样性研究的热点区域。已有不同国家的学者相继对印太交汇区软体动物的多样性、分类与系统演化等方面开展了研究, 并取得了一系列重要的成果。基于此, 本文从软体动物的生物多样性格局、成因、以及其影响因素等角度出发, 对印太交汇区软体动物研究的主要方面进展进行了综述。先后有物种起源中心、积累中心、重叠中心、幸存中心等多种假说被提出以解释其多样性的成因。印太交汇区软体动物生物多样性分布格局与板块构造作用、海平面的变化、海洋环流以及暖池等密切相关。本文也指出了目前研究中存在的主要问题, 分析了未来的发展趋势及面临的挑战, 以期为今后的相关研究提供参考和思路。

印度-西太平洋; 珊瑚大三角; 软体动物; 多样性热点; 特有种; 物种形成

印太交汇区(Indo-Pacific Convergent Area)的珊瑚礁大三角(Coral Triangle)又称印马群岛(Indo-Malay Archipelago)或东印度群岛大三角(East Indies Triangle), 主要覆盖菲律宾、马来西亚、印度尼西亚、巴布亚新几内亚、所罗门群岛、东帝汶等国家和地区。该区域由于地处热带, 虽仅占全球海洋面积的1.6%, 却孕育着全球76%的造礁珊瑚。这些珊瑚礁继而为各种各样的海洋生物提供了良好的庇护和栖息场所, 使得该区域成为全球海洋生物多样性的中心, 素有“海中亚马逊”之称。因其较高的多样性和独特性, 该区域也被认为是生物多样性保护应优先考虑的重点区域(Roberts, 2002; Asaad, 2018)。印太交汇区软体动物物种丰富, 其多样性在全球最高, 被认为是全球软体动物尤其是珊瑚礁生活的软体动物的多样性中心或热点区域(Reid, 1986; Roberts, 2002; Paulay, 2006; Bellwood, 2009)。据估计, 印太交汇区珊瑚礁大三角内分布的软体动物种类接近整个印度-西太平洋种类的60%。软体动物是继珊瑚和鱼类之后, 在印太交汇区最受到研究关注的类群(Hoeksema, 2007)。软体动物在海洋生态系统物质循环和能量交换方面扮演着相当重要的角色, 同时, 该类群常被用来作为评估珊瑚礁生物多样性的指示类群(Wells, 1998)。因此, 对该区域的海洋软体动物生物多样性开展系统研究不仅有助于促进对印度-西太平洋乃至全球海洋软体动物生物多样性的认知, 而且对加深整个珊瑚礁生态系统的理解亦有重要作用。

1 软体动物生物多样性研究概况

软体动物门是无脊椎动物中的第二大门, 种类数量仅次于节肢动物门, 软体动物也是海洋中最大的动物门类(Williams, 2017)。由于多数种类具有石灰质的外壳, 软体动物又统称为贝类。目前, 世界上已报道的软体动物近10万种, 其中约一半的种类(43600±900种)生活在海水中(Rosenberg, 2014)。海洋软体动物不仅种类多, 且分布范围极广, 从两极到热带、从潮间带至数千米的深渊都有分布。软体动物一直是印太交汇区海洋生物多样性研究的关键类群之一。Gosliner等(1996)估算这一区域中有大约60%的无脊椎动物为软体动物。全世界平均每年报道近450个软体动物新种, 其中超过一半采自于印度-西太平洋热带海域(Bouchet, 2016)。Bouchet等(2016)甚至认为, 全球海洋软体动物的物种总数是由物种最丰富的热带印度-西太平洋驱动的。然而, 关于印太交汇区软体动物物种总数, 目前还没有较为准确的报道。Briggs(1995)估算浅海软体动物有6000种, 这个数字明显被低估了, 其种数应远远超过这个数字。Bouchet等(2002)通过宝贝和涡螺的物种数推算印度-西太平洋浅海软体动物种类在11904—99963种之间。

软体动物呈世界性分布, 生物多样性高, 是不同海区的优势类群之一, 特别是在珊瑚礁大三角海域, 显示出最高的物种多样性。数百年来, 该区域一直是世界海洋贝类多样性研究的热点和重点区域。早期有不同国家在印太交汇区开展了海洋生物多样性调查, 如荷兰的西博加(Siboga)探险队于1899—1900年在印度尼西亚海域开展的海洋调查航次, 共采集到腹足类近1200种(Prashad, 1932; Schepman, 1908a, b, c, 1911, 1913a, b); 此外, 代表性的航次还有美国的信天翁号(Albatross)在菲律宾开展的航次(1907—1910年)以及英国的挑战者号科学考察船(HMS Challenger)在西太平洋开展的航次。

该区域内仅部分海域或部分种类的软体动物有过详细研究报道, 大部分的海区和大量的类群尚缺乏研究。Wells(2000)认为, 印度-西太平洋超过60%的腹足纲分布在珊瑚礁大三角区域内。在印度-西太平洋分布的3400余种后鳃类①越来越多的证据表明, 后鳃类并非是一个单系群, 这一分类阶元现已不再使用。(Opisthobranchia)中, 有超过1000种是未经描述的新种, 有563种分布在菲律宾, 646种分布在巴布亚新几内亚。虽然分布在印度尼西亚的种类没有确切的数目, 但相关报道表明该区域的后鳃类生物多样性甚至高于菲律宾和巴布亚新几内亚(Gosliner, 1996; Gosliner, 2000)。Poppe(2008a, b, 2010, 2011, 2017a)在系列图谱《Philippine Marine Mollusks》中报道了分布于菲律宾海域的贝类5835种, 隶属于297科; Bouchet(2008)认为, 菲律宾还有大量的新种和新记录种未被发现和报道, 并估计菲律宾的海洋贝类种类在32000—35000种左右。Poppe(2017b)估计菲律宾软体动物共有10000—12000种, 这一数据应仅包含浅海的种类, 未对深海物种数进行估算。印度尼西亚的贝类种数到目前为止还没有确切的报道, Soegiarto等(1981)指出印度尼西亚海域已报道的双壳类有1000种左右, 腹足类有1500种左右, 其他类群未有详细报道。Kohn(2001)通过调查发现, 巴布亚新几内亚是芋螺科芋螺属生物多样性最高的区域。仅在巴布亚新几内亚东南部两次调查, 就采集到软体动物近1000种(Wells, 1998; Wells, 2003)。Bouchet等(2002)在新喀里多尼亚西部海岸295 km2范围内设置了42个站位, 采集到贝类2738种; 其中32%的种类仅采自于单个站位, 表明该区域的贝类种类具有明显的空间和生境异质性, 贝类物种多样性被严重低估。

相对于浅海, 关于深海贝类的调查和研究报道相对较少。自20世纪80年代起, 法国自然历史博物馆在西太平洋(包括印太交汇区)发起了一项“热带深海底栖生物调查项目(Tropical Deep-Sea Benthos Programme)”, 设置深海站位5000多个, 采集到了大量深海贝类, 尽管目前已发表了数百个新种, 但仍有数千个新种有待描述和发表(Bouchet, 2016)。仅在新喀里多尼亚100m以下就发现了1000多种软体动物, 其中接近60%是新物种, 已在南太平洋诸岛报道了近150个新种(Bouchet, 2008)。Bouchet(2008)估计菲律宾深海软体动物可达到20000种, 而且80%为未报道的新种。在新喀里多尼亚深海软体动物物种数将达到15000种, 而南太平洋将达到23000种(Bouchet, 2009)。Poppe等(2006)对菲律宾周边深海海域的贝类进行了采集, 报道了178种原始腹足目种类, 包括1个新属和70个新种; von Cosel等(2008)在印度西太平洋深海描述了满月蛤9个新属32个新种; 这一区域的小型螺Caecidae科中, 报道了超过80种, 发现新种24种(Pizzini, 2013; Vannozzi, 2019)。不断有深海的新种在此被发现并报道(e.g. Anseeuw, 2006; Hickman, 2012, 2016)。在马努斯热液区不同作者报道了16种软体动物新种(Warén, 2001; Schein, 2006; Sasaki, 2010; Zhang, 2017a, b)。Hickman(2016)认为印太交汇区也是深海软体动物的多样性热点区域, 甚至是深海生物的起源中心之一。Poppe(2017b)对菲律宾软体动物种类进行研究时认为, 200 m以浅的水域有30%的物种是未被报道过的新物种, 水深达到700 m时, 这一比例可上升到70%。相信随着采集范围的扩大以及采集强度的提高, 一定会有大量的未知种类被报道。

2 印太交汇区软体动物高多样性成因的假说

印太交汇区珊瑚大三角面积虽小, 却是全球海洋生物多样性最高的区域。该区域为何具有如此高的生物多样性, 目前仍然没有一个统一的解答, 存在着不同的假说。但各个假说均认为复杂的隔离事件, 尤其是冰期-间冰期海平面的上升和下降, 不断地促进着物种的隔离和分化。其中, 物种起源中心假说(center of origin or speciation)认为, 由于地质结构复杂、生境异质性较高、生物竞争激烈, 该区域的物种形成速率较高, 物种在该区域形成, 并不断向周围海域扩散; 物种积累中心假说(center of accumulation)认为, 在过去的25 Ma, 印太交汇区的气候和洋流不断发生着剧烈变化, 但区域内大量的岛屿始终扮演着避难所和扩散中心的角色, 周围海域的物种不断扩散并汇聚于此; 物种重叠中心假说(center of overlap)强调生境异质性(habitat heterogeneity)的作用, 认为该区域内的生境多样有利于物种的形成, 高生物多样性是印度洋与太平洋物种或周边海域的物种在此重叠分布的结果(Bowen, 2013; Briggs, 2013)。Bellwood等(2009)通过对珊瑚礁鱼类和宝贝的分析支持了幸存中心假说(center of survival), 认为这一区域物种灭绝速率低, 在物种庇护方面的作用比物种形成方面的作用更加重要。

这些假说均可在一定程度上解释该区域内高生物多样性的原因, 而且这些假说也并不是互斥的, 有人认为是多个假说共同造就的。例如, Sanciangco等(2013)的研究同时支持幸存中心假说和起源中心假说, 他们认为, 珊瑚大三角作为物种的“避难所”减缓了这一区域内物种灭绝的速率, 同时不断增加的物种形成速率也增加了物种的丰富度。多样性热点反馈模型(Biodiversity feedback model)认为多样性热点区既是物种起源中心, 又是汇聚中心, 生物由此起源扩散出去, 又返回汇聚于此(Leliaert, 2018)。也有人认为珊瑚大三角在不同时期对生物多样性作用不同, 对珊瑚礁鱼类生物地理历史的重建显示, 在古新世和始新世的时候为物种汇聚中心, 在始新世和渐新世以来为残存中心, 中新世以来为起源中心, 上新世到现代为物种输出中心(Cowman, 2013)。Williams(2007)通过对蝾螺的研究认为, 珊瑚大三角既是物种形成的“摇篮”(起源中心), 又是生物多样性的“博物馆”(汇聚中心)。Briggs等(2013)认同这种观点, 不过他们认为汇聚作用比物种起源更重要。Evans等(2016)对芋螺种群进化历史的研究认为, 这一区域既作为物种最初的起源中心, 又是幸存中心。

3 印太交汇区软体动物主要的物种形成模式

现代生物多样性格局是由物种的形成、灭绝、迁移扩散相互作用造成的。物种形成事件多发是导致高生物多样性的直接原因。在印太交汇区, 物种形成事件可能集中于物种多样性的中心(物种起源中心)或者在周边区域(物种积累中心)或零散分布于整个区域(物种重叠中心)。印太交汇区内软体动物的高多样性是多种物种形成方式共同造就的。值得注意的是, 不同的物种形成模式可能并没有绝对的界限, 尤其是对海洋生物来说, 偶尔的长距离幼虫扩散可以维持不相连的种群间的基因流(Paulay, 2006)。

3.1 异域物种形成

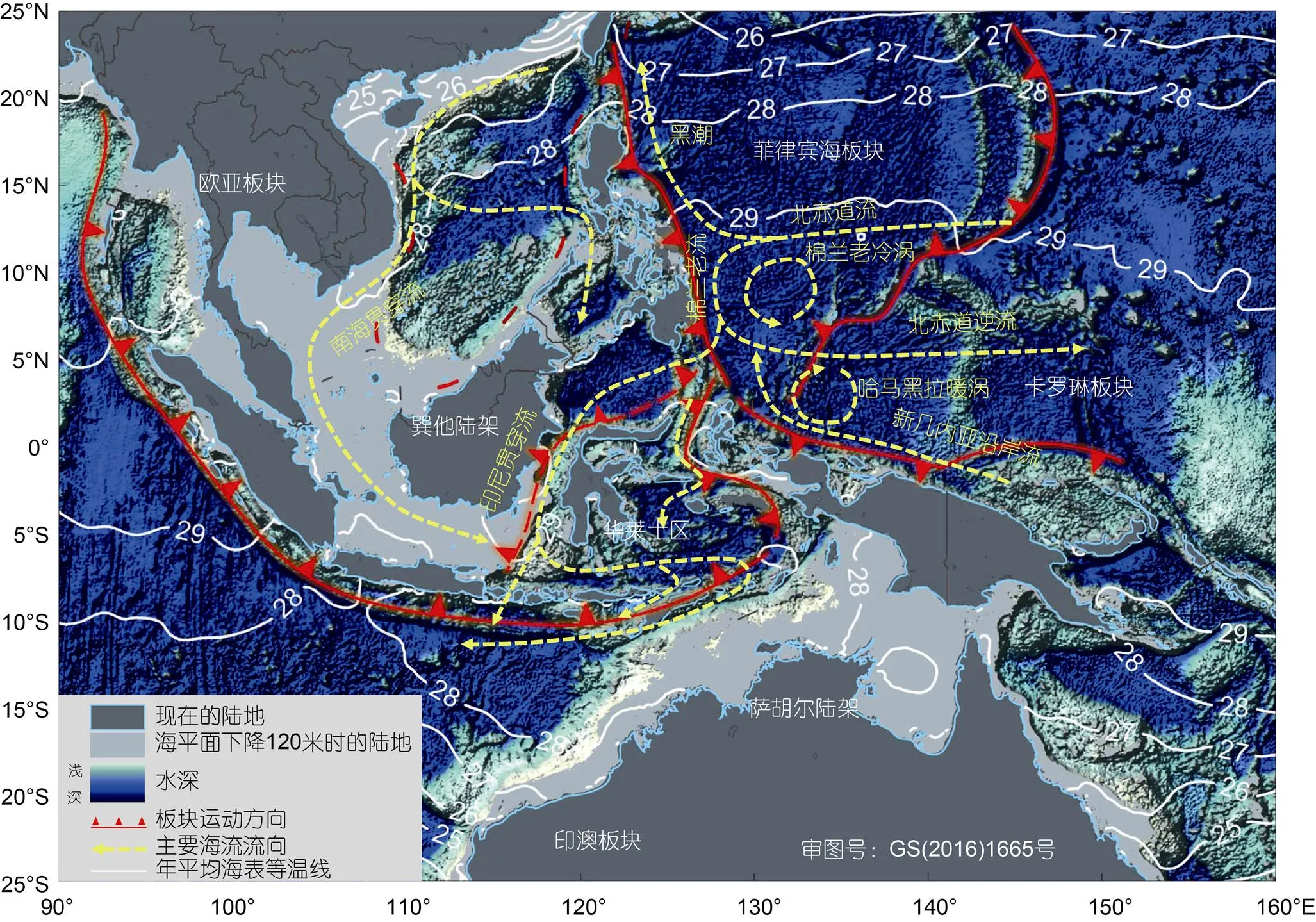

很多研究支持大尺度的地理隔离导致的异域物种形成(allopatric speciation)是该区域物种产生的主要模式。Williams等(2004)通过对滨螺的研究认为, 印度-西太平洋的物种起源于特提斯洋(Tethys), 中新世时特提斯水道(Tethyan Seaway)的关闭使其产生了隔离分化。到上新世-更新世期, 巽他陆架(Sunda Shelf)和萨胡尔陆架(Sahul Shelf)两个大陆架连接印度洋和太平洋, 冰川期海平面下降了120 m, 太平洋和印度洋之间的海盆间相互隔离(Voris, 2000), 在很大程度上阻断了印度洋和太平洋物种之间的基因交流(图1)。这也使得印太交汇区海洋中也可能存在同陆地生物区系一样的华莱士线(Wallace’s Line)(Barber, 2000; Lourie, 2004)。除陆架会对海洋生物造成隔离外, 海流也会对海洋生物产生隔离效应(Ravago-Gotanco, 2007; Carpenter, 2011)。

研究发现, 印太交汇区很多软体动物类群, 如宝贝(Meyer, 2003)、滨螺(Williams, 2004)、蝾螺(Meyer, 2005)、蜑螺(Frey, 2010)、菊花螺(Dayrat, 2014)等, 即便亲缘关系较近的物种, 其分布区没有重叠。Williams等(2004)认为姐妹种间分布区没有重叠或很少重叠, 这表明异域物种形成是主要的物种形成模式。虽然在很多后鳃类姐妹种中发现了同域分布(sympatric distribution)的现象(Gosliner, 1996), 这可能是由于物种的扩散导致。通过异域物种形成模式产生的物种, 最初具有明显的分布界限, 之后物种扩散可能使其分布界限变得模糊或将其分布区重叠(Gosliner, 1996; Kabat, 1996)。然而, 最近的分子研究表明, 很多通过异域物种形成事件产生的物种, 依然保持在原有的分布区(Dayrat, 2014)。即便在同域分布中也存在遗传分化, 或仅需要短暂的异域分布便可产生遗传分化。笠贝(Kirkendale, 2004)、滨螺(Reid, 2006)、砗磲(Kochzius, 2008; Hui, 2016)、蜑螺(Crandall, 2008)等一些物种在印度洋和西太平洋两侧的种群水平有明显的遗传分化。而种群水平的遗传分化正是物种间进化分化的开始(Bowen, 2016)。

图1 印太交汇区的海陆分布、板块构造与主要海流示意图

注: 温度数据来自World Ocean Atlas 2013

3.2 边域物种形成

地质尺度上海平面的变化导致滨海生境的出现与消失, 会加速物种扩散, 并对种群产生隔离作用, 并最终导致了新物种的形成。板块运动产生了一些连接印度洋和太平洋的边缘海盆(Hall, 1998), 由于冰期海平面的上升和下降, 这些边缘海盆与印度洋及太平洋之间曾出现多次的分离和再连接。海平面的下降产生了新的岩石生境或岛屿, 为蜑螺(Postaire, 2014)和小月螺(Williams, 2011)等潮间带生活的软体动物的扩散提供了“跳板”, 加速了种群的扩散, 增加了物种的基因连通, 但之后作为“跳板”的潮间带岩石和岛屿的消失会引起种群的隔离和分化, 产生了新的物种, 这种生境变化引起的边域物种形成(Peripatric speciation)导致了该区域的高物种多样性。除此之外, 海平面上升后, 新形成的珊瑚礁也会被当做物种扩散的“驿站”, 这使得即便幼虫浮游期较短的物种也可以长距离扩散(Jeffrey, 2007)。

3.3 邻域物种形成

除地理隔离或奠基物种(founder)的扩布(如物种在太平洋扩散到孤立的岛屿)可能导致的遗传分化而产生异域物种形成或边域物种形成外, 同一生物地理省内或生物多样性热点地区内的半隔离的邻域物种形成(parapatric speciation)或生态物种形成(ecological speciation)也是该区域软体动物多样性较高的原因(Bowen, 2016)。DeBoer等(2014)对砗磲的研究发现, 珊瑚大三角内生物地理的边界也会对物种基因流通造成隔离, 限制了遗传上的连通性。这一区域内生态梯度的差异增强了隔离效应, 很多物种通过邻域物种形成的方式产生。

4 印太交汇区软体动物多样性影响因素

最近基于分子系统演化研究表明, 印太交汇区中现代软体动物的多样性既有源于特提斯洋的远古分支, 因中新世特提斯海道关闭的隔离而存留在印太交汇区; 也有在晚渐新世或中新世物种适应辐射中形成的形态相似的新物种。印太交汇区软体动物生物多样性分布格局的形成与板块构造作用、海平面的变化、海洋环流以及暖池等密切相关。

4.1 地质历史事件对该区域生物多样性的塑造作用

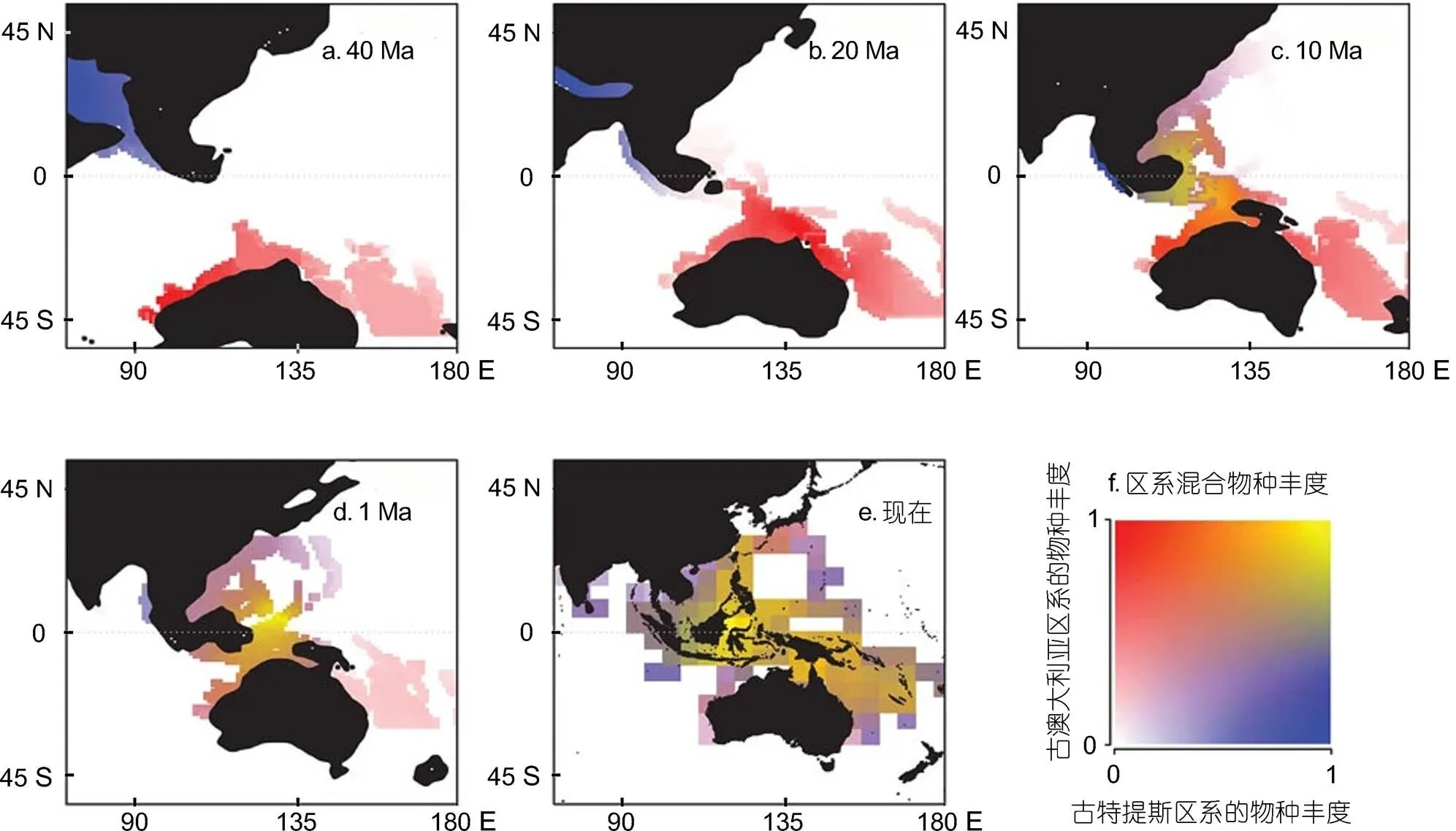

多方面的研究显示, 生物多样性中心在始新世时期位于西特提斯洋, 地质历史事件以及由此引起的海平面变化会造成物种的隔离和新生境的产生, 在促进印太交汇区海洋生物汇聚并加速区域内物种分化方面起着决定性的作用(Heaney, 1998)。澳大利亚板块与欧亚板块东南端在约25 Ma前的碰撞导致了印太交互区发生了较大的地质变化, 使得该区域内浅水区增加, 海岸线增长, 形成了成百上千的岛屿, 并产生了斑块分布的独特生境。同时, 板块的交汇也使得古特提斯区系的物种和澳大利亚区系的物种在此交汇(Leprieur, 2016)(图2)。随后一段时期(约25—20 Ma之间), 含虫黄藻的珊瑚快速分化产生新物种, 珊瑚礁的大量生成为热带软体动物提供了新的生境。到23.7—21.0 Ma以前的渐新世晚期到中新世早期, 该区域内软体动物大量产生新的物种(Williams, 2007; Williams, 2008, 2011)。对该区域内三类无亲缘关系的蝾螺、滨螺、芋螺软体动物的分子系统发育分析显示, 它们在这一时期物种形成速率达到最高峰(Williams, 2008)。中新世时特提斯水道关闭的隔离作用, 也是印太交汇区软体动物多样性的重要塑造因素(Williams, 2004)。更新世海平面变化导致的地理隔离也在一定程度上促进了物种的形成。珊瑚大三角区域是全球单位地理面积内拥有岛屿最多的海区, 许多半封闭的群岛本身就属于典型的异质性生境, 不断促进着物种的分化和形成。地质过程和海洋条件的改变引起的隔离, 使这一区域成为物种形成的中心, 并对整个印度-太平洋生物区系的起源有决定性作用(Carpenter, 2011)。

图2 印太交汇区生物多样性格局演变历史(自Leprieur et al, 2016)

注: 蓝色: 古特提斯区系物种丰度; 红色: 澳大利亚区系物种丰度; 黄色: 区系混合物种丰度

4.2 水文动力条件影响海洋软体动物的基因交流

印度尼西亚贯穿流(Indonesian Througflow)和南海贯穿流(South China Sea Throughflow)穿越印太交汇区, 将太平洋低纬西边界流和印度洋赤道流系连接起来(Wyrtki, 1961; Gordon, 1996; Fang, 2005; Qu, 2006; Schott, 2009), 这也是影响物种基因交流的重要因素(图1)。印太交汇区地形复杂, 海峡通道众多, 来自太平洋和南海暖而淡的海水经苏拉威西海、班达海、爪哇海、弗洛勒斯海, 以及望加锡、卡里马塔、龙目、翁拜等海峡和利法马托拉、帝汶通道, 蜿蜒流入印度洋。板块运动引起的海陆分布变化、气候变化引起的海平面升降等会直接影响海峡的开合, 从而改变海流的路径、流向、流速等, 而其多样的地形地貌结构会对海洋水文动力过程产生显著的影响。海峡是打破海盆间物种基因隔离的重要通道。海峡中的贯穿海流可通过对软体动物幼虫的输运作用介导物种的扩散, 从而增加物种的基因连通。Kochzius等(2008), Nuryanto等(2009), Hui等(2016)发现砗磲沿印尼贯穿流在苏拉威西海、望加锡海峡、弗洛勒斯海、班达海、帝汶海之间有较强的基因交流。而Ravago-Gotanco等(2007)的研究发现, 北赤道流(North Equatorial Current)的不同分支内分布的砗磲种群有显著遗传分化, 这是由于黑潮(Kuroshio Current)和棉兰老流(Mindanao Current), 限制了这两个种群间幼虫和基因的交流。但之前有研究发现, 砗磲在西太平洋基因流与表层海流的方向有很明显的不一致, 甚至基因流垂直于表层海流的方向(Benzie, 1995, 1997), 这可能与该海域上层环流的垂向结构复杂、表层与次表层海流之间显著不同有关。Jeffrey等(2007)对一种幼虫浮游期较短的鲍鱼的研究发现, 海平面的变化导致的隔离虽然使太平洋种群和印度洋种群间存在异域遗传分化, 而在印马群岛内由于海流的作用增加了物种基因的交流, 种群的快速扩张, 足以使这一生物地理历史事件几乎可以忽略不计。印太交汇区的软体动物幼虫发育模式与其分布范围(Meyer, 2005; Jeffrey, 2007)、物种形成方式(Paulay, 2006)、种群的谱系地理(Crandall, 2008)等相关, 而幼虫的扩散直接受海流的影响。物种的进化与发育模式, 会影响物种的分布和物种形成。Hickman(2016)认为, 对于深海海盆, 在海底地形约束下, 深海海流的方向和流速与浅海相比迥然不同, 这会对原始腹足类(vetigastropod)幼虫期扩散产生影响, 最终影响物种的分布和分化。

4.3 暖池对软体动物生物多样性的促进作用

海水温度也是影响海洋生物物种丰富度形成的一个重要因素。珊瑚大三角多样性的形成与暖池也有一定的相关(Sanciangco, 2013)。海水表层温度与多样的生境一样, 对造就该海域高物种多样性有重要作用。暖池维持了该区域表层水温较高的水平(图1), 这为塑造物种多样性提供了能量。印太交汇区热带海域被认为是蝾螺(Williams, 2007)、裸鳃类(Ekimova, 2019)等种类进化模式的源头, 温带甚至寒带的物种和种群也起源于此, 这为物种的扩散和分化提供了物种库。温度是影响物种形成速率的重要因素。温度影响进化速率的原因包括: 一方面, 温度与基因突变速率相关; 另一方面, 高纬度低温物种生长慢、生活时间长, 性成熟时间晚, 世代时间长, 进化就相对较慢。

5 印太交汇区软体动物高特有种的成因

印太交汇区软体动物多样性的另一个特点是有较高的特有种(endemic species)比例(Meyer, 2003; Williams, 2004; Meyer, 2005; Frey, 2010; Dayrat, 2014)。该区域软体动物具有高特有种的现象, 可能与其长距离的扩散有关。某些海洋软体动物可在很小的范围内形成新的物种, 当这些物种通过偶然的机会扩散到距离较远或孤立的栖息地时, 会与之前物种相隔离而产生新物种, 这就导致了印太交汇区周边岛屿有较高的特有种(Meyer, 2005)。广分布的物种在其分布边缘的遗传分化或许是物种形成的起点(Bowen, 2016)。珊瑚大三角作为生物多样性热点区被认为是生物多样性的产生中心, 而其周边的特有种较高的区域被认为是进化的终点, 即便偶尔会有少数物种扩散至此, 能够产生新的特有种, 但不会有进一步的物种进化辐射, 产生更多的物种(Bowen, 2016)。

特有种的出现与软体动物的发育方式密切相关。在菊花螺中, 直接发育的物种无浮游幼虫阶段, 其扩散范围就会非常有限, 就会成为特有种(Dayrat, 2014)。若有浮游幼虫的软体动物, 其可以随海流进行长距离扩散, 分布范围较远。印太交汇区软体动物很多物种的幼虫发育模式仍是未知的, 因此很难解释其在印太的分布模式。物种的发育模式可以从胚壳形态进行推断, 但有些种类的胚壳在成体时会发生磨损, 难以推断其发育模式。

特有种的形成还与地质历史事件引起的栖息地改变有关。在第四纪期间, 海平面频繁而大幅度的下降, 将大片浅海陆架暴露出来变为陆地, 显著改变了该地区的地质特点。有研究表明, 在这段时期内, 在巽他陆架(Hoeksema, 2007; Bellwood, 2012)、澳大利亚西北部地区(Kuhnt, 2004)以及西太平洋岛屿上(Paulay, 1990), 很多生物由于海平面下降导致的栖息地丧失而灭绝。但某些物种在“避难所”中存留下来, 成为该区域的特有种。有些小月螺自更新世的冰川期存活下来, 成为在澳大利亚西北部分布的特有种(Williams, 2011)。

也有研究发现后鳃类软体动物在印太交汇区特有种比例并不高(Gosliner, 1996)。一方面可能是物种后来的扩散使其分布区扩大并重叠, 掩饰了最初隔离形成的各自特有分布区。另一方面, 对这些后鳃类的研究尚不充分, 目前认为的广分布种内可能存在隐存种(cryptic species), 这些隐存种生活在不同的分布区内。印太交汇区内软体动物存在隐存种的现象比较普遍(Crandall, 2008; DeBoer, 2014; Huelsken, 2013)。

Hickman(2016)通过对印度尼西亚深海的瓣口螺的研究认为, 印太交汇区中的华莱士区(Wallacea)也是深海软体动物特有物种的中心, 深海瓣口螺科种类由此向外扩散并进化。欧亚板块和澳大利亚板块之间的碰撞、火山活动、板块俯冲、板块的聚合、深海海沟的形成等因素影响着浅海和深海洋流的运动和走向, 继而塑造着软体动物的多样性及分布格局。华莱士区深海的某些种类与西南印度洋的种类呈现隔离分布的情况(可能是有共同的祖先不同种), 这些种类被认为是新生代之前遗留下来的, 特提斯海道关闭后, 它们被不断隔离分化。但由于对这一区域深海缺乏调查, 缺少新鲜样品, 这一假说缺少解剖学和分子生物学证据。

6 存在的问题及展望

中国关于海洋贝类的研究起始于20世纪20年代, 到现在已有近百年的积累, 在海洋贝类分类学研究领域取得了长足发展与进步, 做出一系列开创性研究成果。然而, 这些研究大多集中于中国的潮间带或浅海水域。自2014年起, 先后对冲绳海槽热液区、马努斯热液区、南海冷泉区、马里亚纳附近的海山区, 以及深海平原和海沟等不同区域进行了调查, 获得了大量深海贝类标本, 其中包括许多未经描述的新种, 推动了我国深海软体动物分类学研究。但是, 总体来讲, 我国对于深海的软体动物分类学研究起步较晚, 研究基础差, 仍缺乏对深海贝类的系统性认知, 亟需继续加强相关调查和研究。当前, 从浅海到深海、从区域性研究到全球性研究已经成为国际研究的总体趋势。

印太交汇区是全球海洋生物多样性中心, 对该区域的贝类生物多样性开展系统研究有助于促进对印度-西太平洋乃至全球海洋贝类生物多样性的理解。然而, 该海区生物区系如何划分仍存争议, 目前该海域的生物地理区系划分多以海峡为界限, 普遍认同华莱士区是古特提斯区系和澳大利亚区系间的过渡区, 然而在海洋生物区系中是否确有华莱士线, 亦或是赫胥黎线(Huxley’s Line)、莱德克线(Lydekker’s Line)仍无定论。地质运动、水文动力环境的变化会对海洋生物产生何种影响?该区域深海生物多样性的起源、演化与扩布机制如何?深海生物的分布格局是否与浅海生物的分布格局相一致?深海类群和浅海类群存在着怎样的系统演化关系?目前, 尚缺乏这方面的研究。解答这些问题须从世界海洋的角度进行系统分析, 扩大研究区域, 通过加强国际合作交流, 进行多学科、跨领域的交叉融合, 从不同角度阐述深海贝类的物种多样性与区系特点、扩散与分化进程以及不同维度间的系统演化关系。

致谢 自然资源部第一海洋研究所徐腾飞博士提供了文中印太交汇区海洋环流特征等方面的资料, 并协助绘制印太交汇区海流示意图。中国科学院海洋研究所黄晶博士对文中印太交汇区地质历史事件等方面的内容给予了修改和帮助。二位提供了宝贵的建议和有益的讨论, 谨致谢忱。

Anseeuw P, Poppe G T, Goto Y, 2006. Description ofsp. nov. from the Philippines (Gastropoda: Pleurotomariidae). Visaya, 1(6): 4—8

Asaad I, Lundquist C J, Erdmann M V, 2018. Delineating priority areas for marine biodiversity conservation in the Coral Triangle. Biological Conservation, 222: 198—211

Barber P H, Palumbi S R, Erdmann M V, 2000. A marine Wallace’s line? Nature, 406(6797): 692—693

Bellwood D R, Meyer C P, 2009. Searching for heat in a marine biodiversity hotspot. Journal of Biogeography, 36(4): 569—576

Bellwood D R, Renema W, Rosen B R, 2012. Biodiversity hotspots, evolution and coral reef biogeography: a review. In: Gower D J, Johnson K, Richardson Jeds. Biotic Evolution and Environmental Change in Southeast Asia. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press, 216—245

Benzie J A H, Williams S T, 1995. Gene flow among giant clam () populations in Pacific does not parallel ocean circulation. Marine Biology, 123(4): 781—787

Benzie J A H, Williams S T, 1997. Genetic structure of giant clam () populations in the West Pacific is not consistent with dispersal by present-day ocean currents. Evolution, 51(3): 768—783

Bouchet P, 2008. The mighty numbers of Philippine marine mollusks. In: Poppe G T ed. Philippine Marine Mollusks, Vol. I (Gastropoda—Part I). Hackenheim, Germany: Conch Books, 8—16

Bouchet P, Bary S, Héros V, 2016. How many species of molluscs are there in the world’s oceans, and who is going to describe them? In: Héros V, Strong E, Bouchet P eds. Tropical Deep-Sea Benthos 29. Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, 208. Paris: Publications Scientifiques du Muséum, 9—24, https://www.researchgate. net/publication/308902446_How_many_species_of_molluscs_are_there_in_the_world%27s_oceans_and_who_is_going_to_describe_them

Bouchet P, Héros V, Lozouet P, 2008. A quarter-century of deep-sea malacological exploration in the South and West Pacific: where do we stand? How far to go? In: Héros V, Corwie R H, Bouchet P eds. Tropical Deep-sea Benthos 25, Mémoires du Muséum National D'histoire Naturelle, 196. Paris: Publications Scientifiques du Muséum, 9—40

Bouchet P, Lozouet P, Maestrati P, 2002. Assessing the magnitude of species richness in tropical marine environments: exceptionally high numbers of molluscs at a New Caledonia site. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 75(4): 421—436

Bouchet P, Lozouet P, Sysoev A, 2009. An inordinate fondness for turrids. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 56(19—20): 1724—1731

Bowen B W, Gaither M R, DiBattista J D, 2016. Comparative phylogeography of the ocean planet. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(29): 7962—7969

Bowen B W, Rocha L A, Toonen R J, 2013. The origins of tropical marine biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 28(6): 359—366

Briggs J C, 1995. Global Biogeography. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 454

Briggs J C, Bowen B W, 2013. Marine shelf habitat: biogeography and evolution. Journal of Biogeography, 40(6): 1023—1035

Carpenter K E, Barber P H, Crandall E D, 2011. Comparative phylogeography of the Coral Triangle and implications for marine management. Journal of Marine Biology, 2011: 396982

Cowman P F, Bellwood D R, 2013. The historical biogeography of coral reef fishes: global patterns of origination and dispersal. Journal of Biogeography, 40(2): 209—224

Crandall E D, Frey M A, Grosberg R K, 2008. Contrasting demographic history and phylogeographical patterns in two Indo-Pacific gastropods. Molecular Ecology, 17(2): 611—626

Dayrat B, Goulding T C, White T R, 2014. Diversity of Indo-West Pacific(Mollusca: Gastropoda: Euthyneura). Zootaxa, 3779(2): 246—276

DeBoer T S, Naguit M R A, Erdmann M V, 2014. Concordance between phylogeographic and biogeographic boundaries in the Coral Triangle: conservation implications based on comparative analyses of multiple giant clam species. Bulletin of Marine Science, 90(1): 277—300

Ekimova I, Valdés Á, Chichvarkhin A, 2019. Diet-driven ecological radiation and allopatric speciation result in high species diversity in a temperate-cold water marine genus(Gastropoda: Nudibranchia). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 141: 106609

Evans S M, McKenna C, Simpson S D, 2016. Patterns of species range evolution in Indo-Pacific reef assemblages reveal the Coral Triangle as a net source of transoceanic diversity. Biology Letters, 12(6): 20160090

Fang G H, Susanto R D, Soesilo I, 2005. A note on the South China Sea shallow interocean circulation. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences, 22(6): 946—954

Frey M A, 2010. The relative importance of geography and ecology in species diversification: evidence from a tropical marine intertidal snail(). Journal of Biogeography, 37(8): 1515—1528

Gordon A L, Fine R A, 1996. Pathways of water between the Pacific and Indian oceans in the Indonesian seas. Nature, 379(6561): 146—149

Gosliner T M, 2000. Biodiversity, endemism, and evolution of opisthobranch gastropods on Indo-Pacific coral reefs. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Coral Reef Symposium. Bali, Indonesia, 23—27, https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/229008075_Biodiversity_endemism_and_evolution_of_opisthobranch_gastropods_on_Indo-Pacific_coral_reefs

Gosliner T M, Draheim R, 1996. Indo-Pacific opisthobranch gastropod biogeography: how do we know what we don’t know?American Malacological Bulletin, 12(1—2): 37—43

Hall R, 1998. The plate tectonics of Cenozoic SE Asia and the distribution of land and sea. In: Hall R, Holloway J D eds. Biogeography and Geological Evolution of SE Asia. Leiden, The Netherlands: Backhuys Publishers, 99—131

Heaney L R, 1998. The origins and dimensions of biodiversity in the Philippines. In: Heaney L R, Regalado J C eds. Vanishing Treasures of the Philippine Rainforest. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History, 12—22

Hickman C S, 2012. A new genus and two new species of deep-sea gastropods (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda: Gazidae). The Nautilus, 126(2): 57—67

Hickman C S, 2016. New species of deep-sea gastropods from the Indo-West Pacific region (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda: Seguenzioidea: Calliotropidae) with a geologic and biogeographic perspective. The Nautilus, 130(3): 83—100, http://apps.webofknowledge.com/full_record.do?product=UA&search_mode=GeneralSearch&qid=1&SID=8DoGc3njM7WTyTPqT7C&page=1&doc=1

Hoeksema B W, 2007. Delineation of the Indo-Malayan centre of maximum marine biodiversity: the Coral Triangle. In:Renema W ed. Biogeography, Time and Place: Distributions, Barriers and Islands. Netherlands, Dordrecht: Springer, 117—178

Huelsken T, Keyse J, Liggins L, 2013. A novel widespread cryptic species and phylogeographic patterns within several giant clam species (Cardiidae: Tridacna) from the Indo-Pacific Ocean. PLoS One, 8(11): e80858

Hui M, Kraemer W E, Seidel C, 2016. Comparative genetic population structure of three endangered giant clams (Cardiidae:species) throughout the Indo-West Pacific: implications for divergence, connectivity and conservation. Journal of Molluscan Studies, 82(3): 403—414

Jeffrey B, Hale P, Degnan B M, 2007. Pleistocene isolation and recent gene flow in, an Indo-Pacific vetigastropod with limited dispersal capacity. Molecular Ecology, 16(2): 289—304

Kabat A R, 1996. Biogeography of the genera of Naticidae (Gastropoda) in the Indo Pacific. American Malacological Bulletin, 12: 29—35

Kirkendale L A, Meyer C P, 2004. Phylogeography of thegroup (Gastropoda: Lottidae): diversification in a dispersal-driven marine system. Molecular Ecology, 13(9): 2749—2762

Kochzius M, Nuryanto A, 2008. Strong genetic population structure in the boring giant clam,, across the Indo-Malay Archipelago: implications related to evolutionary processes and connectivity. Molecular Ecology, 17(17): 3775—3787

Kohn A, 2001. Maximal species richness in: diversity, diet and habitat on reefs of Northeast Papua New Guinea. Coral Reefs, 20(1): 25—38

Kuhnt W, Holbourn A, Hall R, 2004. Neogene history of the Indonesian Throughflow. InClift P, Kuhnt W, Wang Peds. Continent‐Ocean Interactions within East Asian Marginal Seas. Washington: American Geophysical Union, 299—320

Leliaert F, Payo D A, Gurgel C F D, 2018. Patterns and drivers of species diversity in the Indo-Pacific red seaweed Portieria. Journal of Biogeography, 45(10): 2299—2313

Leprieur F, Descombes P, Gaboriau T, 2016. Plate tectonics drive tropical reef biodiversity dynamics. Nature Communications, 7(1): 11461

Lourie S A, Vincent A C J, 2004. A marine fish follows Wallace’s Line: the phylogeography of the three-spot seahorse (, Syngnathidae, Teleostei) in Southeast Asia. Journal of Biogeography, 31(12): 1975—1985

Meyer C P, 2003. Molecular systematics of cowries (Gastropoda: Cypraeidae) and diversification patterns in the tropics. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 79(3): 401—459

Meyer C P, Geller J B, Paulay G, 2005. Fine scale endemism on coral reefs: archipelagic differentiation in turbinid gastropods. Evolution, 59(1): 113—125

Nuryanto A, Kochzius M, 2009. Highly restricted gene flow and deep evolutionary lineages in the giant clam. Coral Reefs, 28(3): 607—619

Paulay G, 1990. Effects of late Cenozoic sea-level fluctuations on the bivalve faunas of tropical oceanic islands. Paleobiology, 16(4): 415—434

Paulay G, Meyer C, 2006. Dispersal and divergence across the greatest ocean region: Do larvae matter? Integrative and Comparative Biology, 46(3): 269—281

Pizzini M, Raines B K, Vannozzi A, 2013. The family Caecidae in the South-West Pacific (Gastropoda: Rissooidea). Bollettino Malacologico, 49(S10): 1—78

Poppe G T, 2008a. Philippine Marine Mollusks: Volume I (Gastropoda, Part I). Germany, Hackenheim: ConchBooks, 759

Poppe G T, 2008b. Philippine Marine Mollusks: Volume II (Gastropoda, Part II). Germany, Hackenheim: ConchBooks, 848

Poppe G T, 2010. Philippine Marine Mollusks: Volume III (Gastropoda, Part III & Bivalvia Part I). Germany, Hackenheim: ConchBooks, 665

Poppe G T, 2011. Philippine Marine Mollusks: Volume IV (Bivalvia Part II, Scaphopoda, Polyplacophora, Cephalopoda & Addenda). Germany, Hackenheim: ConchBooks, 676p

Poppe G T, 2017a. Philippine Marine Mollusks: Volume V (New Records, Completing the Volumes I to IV). Germany, Hackenheim: ConchBooks, 628

Poppe G T, 2017b. The Listing of Philippine Marine Molluks V2.00. Visaya Net, 1—135

Poppe G T, Tagaro S P, Dekker H, 2006. The Seguenziidae, Chilodontidae, Trochidae, Calliostomatidae and Solariellidae of the Philippine Islands with the description of 1 new genus, 2 new subgenera, 70 new species and 1 new subspecies. Visaya, 2: 1—228

Postaire B, Bruggemann J H, Magalon H, 2014. Evolutionary dynamics in the southwest Indian Ocean marine biodiversity hotspot: a perspective from the rocky shore gastropod genus. PLoS One, 9(4): e95040

Prashad B, 1932. The Lamellibranchia of the Siboga expedition. Systematic part. II. Pelecypoda (Exclusive of the Pectinidae). Siboga Expedition Reports, Monograph, 1—353

Qu T D, Du Y, Sasaki H, 2006. South China Sea throughflow: a heat and freshwater conveyor. Geophysical Research Letters, 33(23): L23617

Ravago-Gotanco R G, Magsino R M, Juinio-Meñez M A, 2007. Influence of the North Equatorial Current on the population genetic structure of(Mollusca: Tridacnidae) along the eastern Philippine seaboard. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 336: 161—168

Reid D G, 1986. The Littorinid Molluscs of Mangrove Forests in the Indo-Pacific Region: The Genus(Mollusca, Gastropoda, Littorinidae). London: British Museum (Natural History), 1—227

Reid D G, Lal K, Mackenzie-Dodds J, 2006. Comparative phylogeography and species boundaries insnails in the central Indo-West Pacific. Journal of Biogeography, 33(6): 990—1006

Roberts C M, McClean C J, Veron J E N, 2002. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science, 295(5558): 1280—1284

Rosenberg G, 2014. A new critical estimate of named species-level diversity of the Recent Mollusca. American Malacological Bulletin, 32(2): 308—322

Sanciangco J C, Carpenter K E, Etnoyer P J, 2013. Habitat availability and heterogeneity and the Indo-Pacific Warm Pool as predictors of marine species richness in the tropical Indo-Pacific. PLoS One, 8(2): e56245

Sasaki T, Warén A, Kano Y, 2010. Gastropods from Recent hot vents and cold seeps: systematics, diversity and life strategies. In: Kiel S ed. The Vent and Seep Biota: Aspects from Microbes to Ecosystems. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 169—254

Schein E, 2006. A new deep-sea pectinid bivalve from thermal vents of Manus back-arc Basin (South-western Pacific),n. gen., n. sp. (Pectinoidea: Pectinidae), and its relationships with the generaand. Zootaxa, 1135(1): 1—27

Schepman M M, 1908a. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part I. Rhipidoglossa and Docoglossa. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 1—107

Schepman M M, 1908b. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part II. Taenioglossa and Ptenoglossa. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 108—231

Schepman M M, 1908c. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part III. Gymnologossa. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 233—246

Schepman M M, 1911. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part IV. Rachiglossa. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 247—364

Schepman M M, 1913a. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part V. Toxoglossa. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 365—452

Schepman M M, 1913b. The Prosobranchia of the Siboga Expedition. Part VI. Pulmonata and Opisthobranchia Tectibranchiata, Tribe Bullomorpha. Leyden, Netherlands: E. J. Brill. Siboga Expeditie, 453—494

Schott F A, Xie S P, McCreary Jr J P, 2009. Indian Ocean circulation and climate variability. Reviews of Geophysics, 47(1): RG1002

Soegiarto A, Polunin N, 1981. The marine environment of Indonesia. A report prepared for the Government of the Republic of Indonesia, under the Sponsorship of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Cambridge, England: University of Cambridge, 1—257

Vannozzi A, 2019. The family Caecidae (Mollusca: Gastropoda) from northern Papua-New Guinea. Bollettino Malacologico, 55(1): 72—104

von Cosel R, Bouchet P, 2008. Tropical deep-water lucinids (Mollusca: Bivalvia) from the Indo-Pacific: essentially unknown, but diverse and occasionally gigantic. In: Héros V, Cowie R H, Bouchet P eds. Tropical Deep-Sea Benthos 25, Mémoires du Muséum National d'histoire Naturelle, 196. Paris: Publications Scientifiques du Muséum, 115—213

Voris H K, 2000. Maps of Pleistocene sea levels in Southeast Asia: shorelines, river systems and time durations. Journal of Biogeography, 27(5): 1153—1167

Warén A, Bouchet P, 2001. Gastropoda and Monoplacophora from hydrothermal vents and seeps: new taxa and records. The Veliger, 44: 116—231

Wells F E, 1998. Marine molluscs of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. In: Werner T B, Allen G R eds. A Rapid Biodiversity Assessment of the Coral Reefs of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. Washington, DC: Conservation International, RAP Working Papers, 35—38

Wells F E, 2000. Centres of species richness and endemism of shallow water marine molluscs in the tropical Indo-West Pacific. In: Proceedings of the 9th International Coral Reef Symposium. Bali, Indonesia, 941—946, https://www. researchgate.net/publication/266879354_Centres_of_species_richness_and_endemism_of_shallow_water_marine_molluscs_in_the_tropical_Indo-West_Pacific

Wells F E, Kinch J P, 2003. Molluscs of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. In: Allen G R, Kinch J P, McKenna S Aeds. A Rapid Marine Biodiversity Assessment of Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea - Survey II (2000). Washington, DC, USA: Conservation International, RAP Bulletin of Biological Assessment 29, 39—45, https://www. researchgate.net/publication/228714843_A_Rapid_Marine_Biodiversity_Assessment_of_Milne_Bay_Province_Papua_New_Guinea_Survey_II_2000

Williams S T, 2007. Origins and diversification of Indo-West Pacific marine fauna: evolutionary history and biogeography of turban shells (Gastropoda, Turbinidae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 92(3): 573—592

Williams S T, 2017. Molluscan shell colour. Biological Reviews, 92(2): 1039—1058

Williams S, Apte D, Ozawa T, 2011. Speciation and dispersal along continental coastlines and island arcs in the Indo-West Pacific turbinid gastropod genus. Evolution, 65(6): 1752—1771

Williams S T, Duda Jr T F, 2008. Did tectonic activity stimulate Oligo-Miocene speciation in the Indo-West Pacific? Evolution, 62(7): 1618—1634

Williams S T, Reid D G, 2004. Speciation and diversity on tropical rocky shores: a global phylogeny of snails of the genus. Evolution, 58(10): 2227—2251

Wyrtki K, 1961. Physical oceanography of the Southeast Asian waters. NAGA Report Vol. 2, Scientific Results of Marine Investigations of the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand 1959-1961. La Jolla, CA: Scripps Institution of Oceanography, 195

Zhang S Q, Zhang S P, 2017a. A new genus and species of Neomphalidae from a hydrothermal vent of the Manus Back-Arc Basin, western Pacific (Gastropoda: Neomphalina). The Nautilus, 131(1): 76—86

Zhang S Q, Zhang S P, 2017b., a new species of pectinodontid limpet (Gastropoda: Pectinodontidae) from a hydrothermal vent of the Manus Back-Arc Basin. The Nautilus, 131(4): 217—225

PROGRESS ON MARINE MOLLUSCAN BIODIVERSITY IN THE INDO-PACIFIC CONVERGENCE REGION

ZHANG Jun-Long1, 2, ZHANG Shu-Qian1, 2, JIAO Ying-Yi1, 3

(1. Institute of Oceanology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; 2. Center for Ocean Mega-Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Qingdao 266071, China; 3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China)

The Indo-Pacific Convergence Region (IPCR) is recognized as the highest marine biodiversity region in the world, in which the “Coral Triangle” is included that is well-known for breeding numerous marine species and harboring nearly 60% molluscan species of the Indo-West Pacific. IPCR is an area of outstanding biological interest as a marine molluscan biodiversity hotspot, with exceptional high species richness and striking high endemism. Researches on biodiversity, classification, systematics, and evolution of molluscs in IPCR have been carried out and a series of important results been achieved. We summarized the main progress in this brief review. Hypotheses of the Center of Origin, the Center of Accumulation, the Center of Overlap, and the Center of Survival were proposed to explain the formation and evolution of the marine biodiversity. We believed that the rich marine biodiversity and endemism in IPCR are strongly associated with tectonic activity, sea-level fluctuation, oceanic circulation, and high sea surface temperature caused by warm pool, under which the habitat availability has been continually modified and the heterogeneity been increased. The abiotic changes over geologic time have altered the gene flow and species distribution, and led to the speciation due to geographic isolation, and eventually the molluscan biodiversity in IPCR is shaped. At last, we pointed out that many scientific issues associated with the biodiversity center should be re-explained in the future study.

Indo-West Pacific; Coral Triangle; molluscs; biodiversity hotspot; endemism; speciation

Q178.53

10.11693/hyhz20200700212

* 中国科学院战略性先导科技专项, XDB42030303号; XDA22050203号; “科学”号高端用户项目, KEXUE2020G02号; 中国科学院战略生物资源服务网络计划生物标本馆经典分类学青年人才项目, ZSBR-009号。张均龙, 博士, 副研究员, E-mail: zhangjl@qdio.ac.cn

2020-07-18,

2020-10-28