Paths out of poverty:An eclectic and idiosyncratic review of analytical approaches

2021-03-23

International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI),Washington,D.C.20005,USA

Abstract This paper briefly reviews different debates about approaches for paths out of poverty,considering several views,from the analysis of specific policies to more general or systemic considerations. The contribution of this paper is to present a broad outline of those debates and to serve as an illustration of the complexity of analyzing paths out of poverty. It discusses in sequence,the more microeconomic approach of evaluation of individual policies for poverty alleviation; then it moves to broader issues of growth and development strategies,and macroeconomic policies,and their links to the persistence or reduction of poverty; and finally discusses the topic of institutions,related to how policy decisions are made and enforced in societies at the previous three levels. Finally,the concluding section argues that a successful program to eliminate poverty must integrate all levels of individual policies,macroeconomic programs,development strategies and good institutions.This paper hopes to contribute to that crucial work.

Keywords:poverty,economic growth,macroeconomics,microeconomics,randomized control trials

1.Introduction

On October 14,2019,the Royal Swedish Academy of Science announced that the winners of that year Nobel Prize in economics were Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo(Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) faculty and spouses),and Michael Kremer (Harvard professor). The rationale for the distinction was the use of rigorous statistical methods to assess the impacts and effects of specific policies and other interventions to reduce poverty. The approach utilized by the 2019 Nobel Prize winners focuses on individual policies at a more microeconomic level,but they certainly recognize that poverty is also related to more general and systemic aspects (including the relevance of institutions,a topic that led to the Nobel Prize for Douglass North).

Besides micro policy evaluation and the analysis of institutions’ role,debates about policies for poverty alleviation have focused on more general topics,such as development strategies and macroeconomic management(which were also covered by several of the other Nobel Prize winners over the years).

Therefore,in this paper we will try to briefly review,in an eclectic and idiosyncratic way,different debates about approaches for paths out of poverty,considering several views,from the analysis of specific policies to more general or systemic considerations. Hopefully,the contribution of this paper is to present a broad outline of those debates and to serve as an illustration of the complexity of analyzing paths out of poverty. The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses mainly the type of work done by the 2019 winners,focusing on individual policies at a more microeconomic approach. After that,we discuss in separate sections the topics of,development strategies,macroeconomic policies,and the operation of institutions. In other words,we are moving from microeconomic questions about the paths out of poverty to broader policy issues affecting trends and cycles in growth and development,and finish with institutional considerations about how the related policy decisions are made and enforced in societies. A final section concludes.

2.Randomized control trials (RCTs) and our understanding of paths out of poverty

Randomized control trials (RCTs),an experimental research approach to evaluate the effectiveness of specific policies by randomly allocating units of analysis into treatment and control groups,have steadily gained recognition as the ideal methodfor determining causal effects of interventions in development settings. As in other fields of science,the use of RCTs in development economics research has spread widely,becoming what some have called thegold standardmethodology to inform evidence-based development policy. Decisions on continuing or scaling-up projects are done based on the information collected in these types of studies,and a non-trivial amount of funding budgeted for those projects is spent on this type of evaluation activities.The potential of RCTs to generate unbiased and eventually impactful estimates of program effects has become generally accepted among academia,a recognition that materialized in the 2019 Nobel Prize of economics.

It can be argued that the starting point for the use of RCTs in development interventions goes back to the evaluation of PROGRESA,a national-level conditional cash transfer(CCT) program targeting the poor and ultra-poor launched by the Mexican government in 1997. The evaluation,put in practice by a team of researchers from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI),showed positive effects of PROGRESA on school enrollment,education levels and health outcomes,which motivated the expansion and continuation of the program. Backed-up by the results of several additional RCT-based impact evaluations,PROGRESA,and similar programs with different names,have continued until recently in Mexico (where they are being replaced now),and its CCT mechanism has been replicated in a total of fifty-two countries in Latin-America,Asia and Africa (World Bank 2014).

As the example of PROGRESA shows,results drawn from RCT studies can determine institutional decisions on how to combat poverty in its different manifestations. The increase in the use of CCTs by governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) as development tools is a good example of this influence (FAO and UNICEF 2016;Ravallion 2018). With now twenty years of implementation of these types of studies,we can ask two questions:first,how have RCTs influenced the way we approach poverty eradication programs; and,second,what may be the main drawbacks and criticisms of the method and how those are being overcome. The rest of this section provides a brief summary of how these questions have been responded in the development economics literature.

Answering how the widespread use of RCTs has influenced the field of development economics in a concise way is not easy. Banerjeeet al.(2016) try to do that by compiling a set of areas on which RCTs have had impact according to the authors. Those areas can be divided in two big groups:one that refers to how the use of RCTs has changed the way on which development studies are conducted methodologically; and the other that discusses the actual influence of RCT studies on governmental and non-governmental development interventions. The first group primarily alludes to the methodological refinements in how development research is conducted,particularly regarding how identification strategies1Identification strategy refers to the approach used in the empirical analysis of data to be able to determine causality from the estimation results of econometric models.are defined and implemented. Improvements in seeking natural experiments and the use of quasi-experimental designs such as differences-in-differences,propensity score matching or weighting,regression discontinuity and instrumental variables,all of which aim to generate conditions as close as possible as randomization with a non-randomized sample,serve as examples of that influence. The series of papers of LaLonde (1986),Dehejia and Wahba (1999) and Smith and Todd (2005) provide a good illustration of such an influence on the quasi-experimental research design. Papers such as Angrist and Krueger (1991) and Ludwig and Miller (2007)are good examples of refinements in identification strategies by searching natural experiments in observational data.

With respect to the second group (the influence of RCT studies on development interventions),Banerjeeet al.(2016) provide several examples. There are two main distinctions to make here,one referring to the evaluation of packages or policy programs,and the other focusing on the effectiveness of individual interventions. We have already given an example of a policy evaluation impact,the case of PROGRESA,which led to the continuation and scaling-up of the CCT program. With respect to the other group around single intervention mechanisms for development,the authors provide examples of how RCT tested mechanisms under the United States Agency for International Development(USAID) Development Innovation Ventures (DIV),such as the use of chlorine dispensers or biometric monitoring,have been adopted by private firms,NGOs and governments,each individually reaching more than 1 000 000 people,therefore influencing poverty eradication strategies.

Now,the widespread introduction of RCTs in development economics and the policy research agenda has not come without warnings about its limitations and correct application. For instance,Angus Deaton,another Nobel Prize winner,has cautioned about the potential harmful consequences of the abandonment of theorization and structuration of prior knowledge that can derive from the theoretical simplicity of RCTs (Deaton 2018). The gist of the argument is that insights of the results of these studies are just useful if understood under a structured theoretical body of prior knowledge,especially when dealing with the extrapolation to contexts different to the ones where the experiment took place. This type of criticism is also shared by Barrett and Carter (2010,2020) emphasizing the need of theorization to also correct for the in-sample heterogeneity among different individual types or population subgroups that will cause the estimated treatment effect to be a weighted average of the heterogeneous effects,precluding a correct interpretation of the estimate. The issue of heterogeneity,for instance,becomes very important to understand the effects of those common intervention mechanisms that involve information dissemination or influence the recipient’s expectations. The ability of each participant to comprehend and interiorize the information given in the intervention can cause the non-random allocation of the treatment among the targeted population,the source of heterogeneity coming from unobserved characteristics that likely influence also the measured outcomes of interest.

Other criticisms towards the use of RTCs in development include ethical concerns from both the deprivation of much needed resources to control groups and the nuances behind the implementation of informed consent in different contexts and types of experiments (Barrett and Carter 2010).Some other methodological issues have been also pointed out,such as the spurious significance of treatment effects due to the Fisher-Behrens problem2The Fisher-Behrens problem can occur in the estimation,through parametric procedures (typically two-sample-t-statistic tests),of the differences in the means of two populations that have different standard deviations. If variances are not equal,the t-statistic does not follow a t-distribution,but the Behrens-Fisher one. If estimation is not adjusted to correct for this,the problem can lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis of both means being equal less often than the predetermined significance level,therefore increasing the probability of finding significant differences between groups (Deaton 2018).or the complication of determining treatment effects between population subgroups defined by their ranking in a determined variable distribution,when the distributions of treatment and control groups although equal asymptotically in mean,differ in shape (Deaton 2018).

To conclude this section,the expansion of RCTs to generate knowledge about the poverty eradication impact of single mechanisms and intervention packages is unquestionable,as noted in the previous reference to being called the gold standard of evidence-based policy.Borrowed from other science fields where RCTs were first implemented,such as medicine,their introduction to the development economics research emerged as a cure to the skepticism about the capacity of observational studies to control for observable (but unnoticed by the researcher)and unobservable confounding factors,all of which may bias the interpretation of the impacts of specific interventions.However,unlike in the field of medicine,the absence of a well-informed and structured theory about the impact mechanisms is common in economics,generating doubts on both the internal and external validity of the experiments,in part due to lack of understanding of heterogeneous impacts.On the other hand,the influence of RCTs on the refinement of identification strategies is of great value,and RCTs can be a very useful research complement when accompanied by a well-developed theory that supports the experiment design. But no methodology by itself can provide a full answer to every policy issue,and,therefore,the approach should be a wholistic and comprehensive understanding of the cumulative knowledge that we have about the problem at hand and possible solutions.

Furthermore,the implementation and outcomes of evidence-based policies at the micro level may also depend on the operation of institutions and the general performance of the country in other macroeconomic indicators,all topics that are discussed in the next sections.

3.Growth and development strategies,and paths out of poverty

There is a general consensus that,all things equal,higher trend growth leads to lower poverty (Dollar and Kraay 2001;Ravallion 2004). Therefore,a powerful path out of poverty is to ensure sustained growth. High and sustained growth also helps strengthen the fiscal position of governments,and those public resources can be used to finance policies and programs that favor the poor. On the other hand,low growth punctuated by crises weakens the fiscal position of countries and may lead to cuts in public programs in support of economic growth,social needs,and the poor. In general,it is crucial not only to sustain high average trend growth that is income-distribution neutral or,better,pro-poor,but also to avoid economic crises that might inflict long-lasting damage to the already low levels of human and physical capital of the poor and vulnerable (Lipton and Ravallion 1995).

3.1.Growth fundamentals or structural transformation

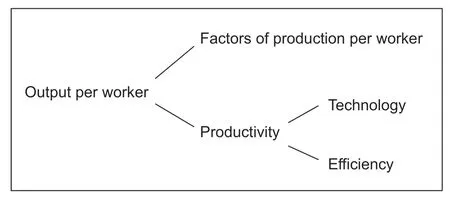

Traditional growth theory focuses on certain “fundamentals”as in Fig.1,from Weil (2009),which is mostly a narrative from the supply side,based on the traditional Solow–Swan model.

Demand is less relevant in this setting,3Solow (2005) has acknowledged the omission of demand considerations as a weakness of the growth theory based on this model.given that it is assumed that some variation of Say’s Law would be operating. Then with aggregate supply defined byQ=f(Physical capital,K; Labor/Human capital,HK;Technology/Productivity,A),the path out of poverty requires accumulation of physical and human capital,plus improvements in productivity. The latter depends on technology (the available knowledge about how factors of production can be combined to produce output) and efficiency,a residual,not explained by factors of production or current technology. This residual may depend on other aspects,related to policies and institutions (but the latter may affect accumulation factors of production and technological developments).

Therefore,the path out of poverty in this setting is to accelerate growth through the general policies and institutions that affect the fundamental aspects of factor accumulation and productivity as shown in Fig.1.

Fig.1 Growth fundamentals. Source:Weil (2009).

A different view in development analysis (as exemplified in Rodrik 2016),is the one based on the notion of“structural transformation,” starting with the models of the dual economy (Lewis 1954; Fei and Ranis 1966). They differentiated between a traditional sector (“agriculture”)and a modern sector (“industry”) of the economy. In this approach accumulation,innovation,and productivity growth would take place in the modern sector,while the traditional sector,was backward and stagnant. Growth in this view depends on moving resources (labor and capital) from the traditional sector (with lower productivity) to the modern and more productive sector.

3.2.Industrialization strategy and sectoral approaches

Based on those ideas,many developing countries after World War II followed policies that saw the role of agriculture as subordinated to the needs of the industrialization. In the classical analysis of Johnston and Mellor (1961) agriculture would help industrial development by transferring labor to industry; providing food (or “wage goods”) and agricultural raw materials; generating savings from rural households that could be used to finance investments in industry; and providing foreign currency through exports to import the machinery and intermediate inputs needed by the industrial sector.

Industry was supposed to have different positive political and social externalities for the society (discussed,for example,in Kerret al.1964) as well as economic ones.Economic arguments in favor of industrialization included avoiding what was considered declining terms of trade for countries exporting agricultural products (or primary products in general) compared to countries exporting industrial goods (Prebisch 1950,1968; Singer 1950). Also,what has been called “high development theory” (Krugman 1994) considered that industrialization generated positive outcomes such as economies of scale,technological spillovers,backward and forward linkages,and strategic complementarities. Another issue was macroeconomic stability:policymakers considered that industrialization was going to make the economy less vulnerable to external shocks,thus avoiding macroeconomic crises (a topic discussed later).

In summary,according to these arguments,growth and the path out of poverty depended on industrialization,while agriculture played only a subordinated role. Some of these ideas were embedded in what was called import substitution industrialization (ISI),an approach that a variety of developing countries followed during the 1950s,1960s and 1970s. It should be noted that such industrialization was focused mainly on the domestic market (hence,the notion of “import substitution,” different from industrialization for exports,discussed later).

But the ISI strategy led to early concerns about the adequacy of a development strategy that appeared to discriminate against the agricultural sector by maintaining low agricultural prices to help urban populations and further the process of industrialization. Schultz (1964)argued that farmers in developing countries reacted with economic rationality to changes in prices and incentives(they were “poor but efficient”). With agricultural resources efficiently utilized,there were no gains by transferring labor and savings to other sectors. A better strategy would be to support the agricultural sector through investments in technology and physical and human capital formation in rural areas. The Green Revolution of the 1970s was based on the idea that there is a technological solution to the rural problem,emphasizing better productivity.

This idea led to the creation of the national centers of agricultural research as well as the international counterpart that eventually conformed the Consultative Group in International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The Green Revolution also overshadowed in good measure the other two main approaches of dealing with poverty in the rural areas at that time:agrarian reform (the redistribution of land that would create family farms that favor labor intensive farming methods) and community development (a political rather than economic approach,that emphasized participation and organization at the local level,through cooperative efforts based on self-help and mutual aid to solve poverty; Holdcroft 1976).

Other studies in the 1970s evaluated critically the overall development approach (Littleet al.1970; Balassa 1971). Those studies argued that the ISI strategy,by not following comparative advantage,slowed growth and led to more macroeconomic instability. Also,the notion of deteriorating terms of trade was disputed (for an overview of those debates at that time,see Balassa 1989). Further,it was also argued that poverty alleviation in developing countries was impaired by policies that protected capitalintensive industrialization and discriminated against agriculture,negatively affecting employment and income distribution.

The obvious fact that poverty in many developing countries was concentrated mainly in rural areas led to the conclusion that greater attention should be given to agricultural and rural development. Cheneryet al.(1974)presented the case for an investment program centered on the poor,especially in rural areas. This led to the territorial rural development projects (which were called Integrated Rural Development) of the 1980s. Another influential book (Lipton 1977) criticized the “urban bias” in policies and investments,arguing that the poor remained poor in developing countries because public expenditures and economic policy in general benefited urban groups who were better positioned to pressure governments to defend their interests.

However,in many cases,the specific approaches focusing on the rural poor (agrarian reform,community development,and integrated rural development) still operated within the context of the ISI strategy,which according to its critics,was the main reason for low growth and the persistence of poverty. A period of revision of development strategies ensued.

3.3.Structural adjustment,export-oriented industrialization,and the revalorization of agriculture

The policy consensus moved towards changing the broader development strategy by eliminating inefficient industrial protection and changing a macro-trade regime that was considered to operate against the agricultural sector,while revamping the inefficient and many times contradictory sectoral agricultural interventions (World Bank 1986). Those ideas became the substance of structural and sectoral adjustment programs implemented by many developing countries in the 1990s.

Also,the experience of mostly Asian developing countries that both supported agriculture and followed an export-led strategy of industrialization provided a counterexample to the ISI strategy with a subordinated agriculture. The structural transformation in Asian countries found adequate demand at the global level,particularly in the United States and other developed countries. In particular,such development strategy allowed China to move about 900 million people from poverty. A similar strategy for other developing countries may now be more constrained in the current context of global trade disputes.

Another aspect of the debate was the revalorization of agriculture for a pro-poor development strategy. Empirical studies showed that agricultural growth seemed to have larger positive multiplier effects on growth in general,but also had larger effects on poverty reduction than growth in other sectors (Lipton and Ravallion 1995; Eastwood and Lipton 2000; Christiaensenet al.2010).4There were exceptions to these findings,such as developing countries with large inequalities in landholdings (Eastwood and Lipton 2000). Also,the correlation between agricultural growth and poverty reduction weakens in richer countries.

Growth in agricultural activities appeared to help reduce poverty through different channels,which were also relevant for food security:(1) increases producers’income; (2) generates more employment opportunities in rural areas; (3) helps to stabilize food supply and prices for net buyers; and (4) produces general multiplier effects on the rest of the economy from agricultural growth and demand (on the multipliers see Haggbladeet al.2007).5It should be noted,however,that an agricultural-based strategy for low-income developing countries is not without doubters:some consider that the sector cannot generate the necessary dynamic effects (see Haggblade and Hazell (2010),Chapter 1,for a review of the debate related to Africa; and Christiaensen et al.(2010) for a consideration of the issue in developing countries in general).

Therefore,for many low-income developing countries,where agriculture continues to be very important for production,employment,and exports,and where most of the poor work,agricultural development was again considered crucial for poverty and hunger alleviation. A relevant line of work within this tradition has been the ranking of impacts on growth,productivity and poverty of different types of investments in and for the agricultural sector (see Fan 2008).

3.4.“Basic needs” approach

So far,we discussed the impacts on paths out of poverty of the level and sectoral composition of growth. A different development strategy for poverty alleviation was the “basic needs” approach,which emerged in the late 1970s. It was argued that objectives such as growth,or even employment and income redistribution,were means to the more concrete objective of attending to the specific basic needs of the population (mostly defined by non-financial indicators,such as the level of education or mortality rates,and including both “material” and “immaterial” components),especially for the poor and vulnerable (Streeten and Burki 1978).The basic needs approach implied an important role for the public sector in the provision of certain public services and required improvements in the provision and access to effectively reach the poorest sectors. This approach led to the creation of the index of Human Development by the United Nations,which highlighted other dimensions of social improvement in addition to growth and incomes,and later inspired the Millennium Development Goals and the current Sustainable Development Goals.

In the second half of the 1990s it also led a new type program began to be implemented in Latin America (such as the case of Mexico’s “PROGRESA,” already mentioned).Although the details vary,they basically consist in income transfers given mostly to women heads of households,but with specific requirements related to attendance at school and health check-ups for their children,attempting to break the intergenerational transfer of poverty within the family.They have been complemented by other institutional and policy changes related to education,health and labor markets,trying to improve the existing supply of services that cover the target population.

In the agricultural sector,these programs are currently being expanded to include not only income transfers for poverty reasons,but also grants for productive and environmental purposes for poor farmers.

4.Crises,macroeconomic management,and poverty

Even if governments follow adequate development strategies and microeconomic policies (the topics of the two previous sections),poor people are affected by many shocks,6For instance,Sinha et al.(2002) consider that poverty is associated to what they call “damaging fluctuations”:(1) violence (wars,civil strife,community violence,and domestic violence); (2) natural disasters; (3) harvest failure; (4) disease or injury; (5) unemployment or under employment; and (6) shocks that worsen the relative prices of food,especially when compared to income. This section focuses on macroeconomic aspects linked to (5) and (6).some of which are policy related.

In this section we discuss shocks related to macroeconomic crises,with their consequence of declines in production and employment,dramatic devaluations of the local currency,and high inflation,all of which are major causes of poverty and food insecurity (Díaz-Bonilla 2008).

Much of the work on those topics has focused on domestic macroeconomic policies,but it is necessary to also consider the conditions prevalent in the international economy,such as the impact of world recessions and volatility in world commodity prices and trade and capital flows (Díaz-Bonilla 2015).

4.1.Domestic macroeconomic problems

The main domestic macroeconomic problem from the point of view of poverty is how to manage aggregate demand to ensure stable growth,avoiding economic crises. If this is not done properly,the economy may experience recessions(if aggregate demand is below aggregate supply) or inflationary pressures and balance of payments crises (if aggregate demand significantly exceeds aggregate supply).Consequently,the economic policies included in these programs are mainly monetary,fiscal,exchange rate,and trade measures aimed at aligning the levels of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. In addition to the alignment of aggregate demand and aggregate supply,another macroeconomic policy issue is how to ensure adequate values for macro prices (such as the exchange rate).

Economic crises,with their different fiscal,financial,trade,and social components,are particularly dramatic manifestations of imbalances between aggregate demand and aggregate supply and/or of misalignments in macro prices. Crises tend to affect long-term growth prospects and increase poverty and food insecurity because they impair installed productive capital,and their recurrence increases uncertainty,thereby reducing investment and future capital. Crises also negatively affect poverty more directly than only through lower overall growth. For instance,higher unemployment and its persistence over time deteriorate the human capital of the poor,now and in the future (as is the case when children are taken from school to help support the family). Health,nutrition,and education indicators usually worsen during economic crises,further affecting the human capital of the poor and contributing to the persistence of poverty (Dercon and Hoddinott 2005). Crises may compromise the limited productive capital of the poor,if,for instance,assets like livestock must be sold to help small farmers face economic shocks (Lipton and Ravallion 1995). The poor depend more heavily on public services that could be cut by economic crises. Crises can worsen income distribution,making it more difficult for the growth recovery to reduce poverty (Lustig 2000). All those negative effects on the poor also affect the performance of the whole economy,which is an additional justification for the provision of publicly funded safety nets (Lustig 2000).

The negative effect of economic volatility (as a recurrence of economic slowdowns and crises) on poverty seems to be more noticeable in the low-income developing countries of Africa but has also affected middle-income countries suffering from financial crises. The Inter-American Development Bank (1995) estimated that if Latin America have had a level of macroeconomic stability similar to industrialized countries,the poverty headcount would have been reduced by one-quarter in the 1980s and 1990s.Also,episodes of hyperinflation or very high inflation have been accompanied by large increases in poverty and food insecurity (see Díaz-Bonilla 2008,2015).

Another important channel of influence for macroeconomic policies is through government revenues,which decline in recessions,negatively affecting the possibility of implementing safety nets (such as food subsidies or other poverty-oriented programs) and financing public services and investments in health,education,and related areas.Crises also tend to leave a legacy of public and private debt,weakening fiscal accounts and banking and financial systems,all of which impacts negatively on growth,efficiency,and equity.

Many of the economic crises in developing countries result from inadequate domestic macroeconomic policies,such as large fiscal deficits,in part financed by excessive money creation,and fixed exchange rates that end up being grossly overvalued; in turn this combination leads to balance of payment problems,which force sharp devaluations,affecting the banking system (particularly if it is “dollarized”),and generating unemployment and inflation (Díaz-Bonilla 2015).

4.2.International macroeconomic developments

However,not all macroeconomic crises are of domestic origin. World economic downturns and recessions,such as those experienced in 1975,1982,1991–1993,and 2009,led to increases in poverty in a variety of developing countries,and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is expected to cause even worse outcomes. Also,volatility in global capital flows,interest rates,and prices of commodities affects growth and poverty in developing countries.

In the case of Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC),there were also important negative effects on poverty during the debt crises of the 1980s. The average poverty headcount ratio increased by about 6 percentage points using domestic poverty lines (Lustig 2000). In terms of the impacts on other social variables,Paxson and Schady(2004) found that the 1988–1992 crisis in Peru led to increases in infant mortality and obvious deterioration in nutritional conditions among children. A second wave of debt crises erupted in developing countries during the 1990s,first in Mexico in 1995 and then in East Asia (1997),Russia (1998),Brazil (1999),and Argentina (2001). The percentage of poor people increased in LAC and sub-Saharan Africa (SSA),and also in specific Asian countries more affected by the financial crisis (such as Indonesia,the Philippines,South Korea,Malaysia,and Thailand) (see Lustig 2000 for data on LAC; and Fallon and Lucas 2002 for specific Asian countries; Díaz-Bonilla 2008). Besides the immediate impact on poverty,another issue is whether there have been other more lasting effects on the human capital of the poor as a result of reductions in health and education investments by households and the public sector(as documented by Lustig (2000) for LAC and Fallon and Lucas (2002) for some Asian countries).

The commodity cycles also affect developing countries,although with clear differences across regions (the share of primary products is smaller in Asian countries and larger in SSA and Middle East and North Africa,and the commodity composition also varies; see Díaz-Bonilla and Robinson 2010). This debate has a long history in development theory,from the Prebisch-Singer theory of the declining terms of trade (Prebisch 1950,1968; Singer 1950) through the price stabilization schemes of the 1970s to the debates during the price spikes of 2008 and 2011. Different studies have analyzed the impact of commodity prices on developing countries,and have shown important effects (for instance Deaton and Miller (1995) and the decline in growth in SSA from 1970–1975 to 1980–1985; Collier (2005),for a subset of commodities in a sample of 56 developing countries during the period 1970–1993; and Díaz-Bonilla (2015) with a review of different studies).

In summary,any discussion of the effects of policy must consider domestic and international factors,and the interaction between them,both for the start and management of crises. This is particularly the case during the current pandemic.

4.3.Macroeconomic policies

What can developing countries do to maintain growth and help the poor in the face of those external shocks?Basically,they should always be prepared for external shocks (recessions,changes in capital flows,gyrations in commodity prices,etc.),and try to soften the blows,moderating the internal impact. For exogenous economic shocks that are in line with history,the common policy prescriptions include the following:

1) Strengthen the fiscal position of the public sector,reducing debt ratios and building countercyclical funds during good times.

2) Avoid rigid and appreciated real exchange rates.Overvaluation of the exchange rate leads to trade deficits and is also associated with excessive accumulation of foreign debt,low growth,and widespread adoption of a foreign currency (or “dollarization of the economy”). It often ends up in damaging economic,financial,and balance-ofpayment crises,which increase poverty and food insecurity.

3) Monetary,financial,and exchange rate policies must be considered in an integrated framework that defines a realistic inflation target,utilizes the different monetary instruments in a coordinated manner,and ensures that the exchange rate is properly valued.

4) Maintain reasonable levels of reserves in the central banks as a precaution against possible global declines in growth and commodity prices,as well as reversals in capital flows.

The current crisis linked to the coronavirus pandemic is a different and more dangerous exogenous shocks that will more likely require unconventional monetary policies to expand domestic liquidity in local currency,and segmentation through controls of the markets for domestic and foreign currencies (Díaz-Bonilla 2020).

5.Institutions and poverty

5.1.Institutions:meaning,importance and emergence

To be able to disentangle the effect of institutions on determining the prevalence of poverty,we should first define what is an institution. Douglass North,the pioneer in this field,argued that “institutions are the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction.They are made up of formal constraints (e.g.,rules,laws,constitutions),informal constraints (e.g.,norms of behavior,conventions,self-imposed codes of conduct),and their enforcement characteristics. Together they define the incentive structure of societies.” (North 1994:p.360). The necessary next question is why should institutions concern us in the discussion about poverty? In general,the answer is that “good institutions” allow more people to contribute to,and benefit from,improvements in societal conditions. For instance,they facilitate creativity and innovation; support exchange and trade,which leads to the division of labor and specialization and the emergence of economies of scale; encourage investment,as well as cooperation and sharing information; lead to stability and less uncertainty,and even peace. At a minimum,good institutions limit negative outcomes,such as physical damage,expropriation,rule of the stronger,coercion,uncertainty,instability,and violence.

A well-known example of the institutional approach is the book by Acemoglu and Robinson (2013). They criticize explanations about prosperity and poverty that are based on geography,culture,and ignorance about better policy options,and emphasize the role of institutions:a country with institutions that they call “extractive” (where oligarchies govern only in their interests and at the expense of large sections of the population) is not going to design and implement good policies that help develop its economy and reduce poverty,while developed countries are those that have “inclusive” institutions (where more diffuse power and popular participation lead to policies that are more conducive to the common good).

But the argument seems somewhat circular:almost by definition the countries that are currently developed would have had inclusive institutions with good policies,while the undeveloped countries would have had extractive institutions and bad policies. The authors include some caveats about the prospect of growth happening under extractive regimes (but they consider that growth would be short lived),and the possibility of paralysis under inclusive institutions.7Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) only briefly consider the case when inclusive institutions become “excessively” so (but without explaining the reasons for that condition or what would be “excessive”),and the negative impacts for development that condition may have,when it leads to paralysis in the decision-making system or to violent clashes between opposite groups.

A more important point is that,with exceptions,the literature on institutions,either takes them as a given,or has superficial explanations regarding how they emerged and evolved. There are authors with more relevant explanations of where institutions come from,such as Diamond (1997),which has global coverage,and Engerman and Sokoloff(1994,2002),which focus on the Americas. These authors show how the endowment of natural resources,climate,and geography are important factors that define the productive structure (particularly the agricultural sector),which,in turn,shapes the institutions (see also Moore 1966; Landes1998).8Quoting Engerman and Sokoloff (2002):“We highlight the relevance of stark contrasts in the degree of inequality in wealth,human capital,and political power in accounting for how fundamental economic institutions evolved over time. We argue,moreover,that the roots of these disparities in the extent of inequality lay in differences in the initial factor endowments … The clear implication is that institutions should not be presumed to be exogenous; economists need to learn more about where they come from to understand their relation to economic development.” (pp.35–36).

The next level of analysis after the discussion about the origins of institutions is on the influence of institutions on the “quality” of public policies,as defined by six features:1)stability,2) adaptability,3) coherence and coordination,4)effective implementation,5) orientation towards the public interest,and 6) efficiency. Some analysts contend that these characteristics may be more important for development and poverty alleviation than the specific content of the policies. It is also argued that the process through which policy measures are debated,approved and executed (the institutions of the process of making public policies or PMP)has a strong impact on the quality of public policies (Inter-American Development Bank 2006; Spiller and Tomassi 2008; Stein and Tomassi (eds) with Spiller and Scartascini 2008).

In this analysis,public policies in developing countries are of low quality due to the functioning of the PMP:Those policies result from a non-cooperative game with short-term horizons; with few of the continued interactions that would help build confidence and stability; without institutional frameworks for reaching agreements and consensus; and with too many “players” or agents. Also,such short horizons favor what has been called “the winner takes all,” as well as leading to policies that try to over-expand consumption in the short term,which usually is unsustainable and ends in economic crises. In addition,if the time in public service is short,there is the temptation of taking advantage of the moment of being in government to get rich.

5.2.Policies and the policy-making process

The previous sections discussed microeconomic and macroeconomic issues related to “good policies” that can achieve positive results to combat poverty; but following the arguments in this section that “good institutions” are needed to design and implement “good policies,” the main question then is what can poor countries do to develop the right institutional setting.

Banerjee and Dufflo (2011),reacting to the criticism that they are answering only “small questions,” argue that their micro perspective is nonetheless helpful:first,even within“bad” overall institutions there is margin to improve specific individual policies (and they argue that we all owe the poor to do that); and second,that improving what seem “small”policy interventions may have some “upward” influence,as people become more aware of what works and thus exercise pressure to change more general institutions and policies.

Other authors,such as Easterly (2008),criticize the attempts at imposing institutions from developed countries onto the social and political fabric of developing countries.9It can be argued that the expansion of the European Union has been a successful case (at least until recently) where countries that want to get in to receive the economic advantages of forming part of the Union must adjust their institutions according to some specific guidelines (Schimmelfennig 2005).This line of analysis mainly assumes that,given political and economic freedom,people in developing countries would create the institutions that are more adequate for them. But it is also true that ensuring political and economic freedom would also require strong institutions that limit the power of oligarchies and mediate the inevitable conflicts of interests and values in any human society.

Another approach to the large question about “good institutions” leading to “good policies” is the literature that focus,more narrowly,on the process of designing,approving,and implementing public policies -the PMP mentioned before. This line of analysis focuses on the characteristics of the PMP that prevent the prevalence of policies that favor the dominant actors of the moment and ignore others,and may lead to more effective,sustainable,and flexible policies. An appropriate PMP that leads to more cooperative outcomes (with whatever form of government)is one that,borrowing from the theory of repeated games,have the following characteristics:1) the number of key political actors is neither too large nor too small; 2) they have longer time horizons and more frequency in their interaction (i.e.,strong intertemporal linkages that require to maintain a “good reputation” with other actors); 3) there is public information about policy and political moves,which then become widely observable; 4) there are institutional arenas in which they can interact (which may be legislatures or cabinet meetings,or outside the government,councils for public-private consultations); 5) there are enforcement mechanisms that bind political actors to their commitments;and 6) the short-run payoffs from noncooperation are not too high (Stein and Tommasi 2008).

Presumably,a PMP with those characteristics may help design and implement adequate individual interventions,development strategies and macroeconomic policies. Still,the question of how to build such PMP remains.

6.Conclusion

This paper tried to provide an overview,admittedly eclectic and idiosyncratic,of the policy debate about paths out of poverty. The somewhat unsatisfactory answer is that we need to consider all the levels analyzed to eliminate poverty. Certainly,it is necessary to rigorously evaluate the impacts of individual policies as the 2019 Nobel Prize winners and other following that approach have shown.But those individual policies are embedded within broader development strategies and macroeconomic frameworks.And institutions,or at least the nature of the policy making mechanism discussed,seem relevant for the design and implementation of “good policies.” An integrated approach to ensuring that the poor could,finally,have adequate paths out of poverty must articulate all levels of individual policies,macroeconomic programs,development strategies and good institutions. From the point of view of policy analysis there is a vast area of research not only within each one of the four topics discussed but also regarding the interactions across them. We hope that this paper may be useful to place that crucial future work in a broader context. Finally,it should be noted that the current COVID-19 pandemic will certainly require that developing countries utilize all policy instruments at their disposal to avoid a tragic increase in global poverty.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

杂志排行

Journal of Integrative Agriculture的其它文章

- Paths out of poverty:lnternational experience

- Elite capture,the “follow-up checks” policy,and the targeted poverty alleviation program:Evidence from rural western China

- Income effects of poverty alleviation relocation program on rural farmers in China

- Do rural highways narrow Chinese farmers’ income gap among provinces?

- Does poverty-alleviation-based industry development improve farmers’ livelihood capital?

- lmpacts of formal credit on rural household income:Evidence from deprived areas in western China