Indirect Request’s Processing Based on Force-Dynamic Theory

2021-03-03WUYi-mei,CHENZheng

WU Yi-mei,CHEN Zheng

This paper focuses on one of the indirect speech acts, indirect requests. This paper firstly introduced how force-dynamic theory works and analyzed the same situation of indirect request that involves different utterances by applying Talmy’s force-dynamic theory. It reveals how indirect request is processed between speakers and listeners by adopting patterns explanation, and also gives cognitive interpretation of it. Besides, from cognitive linguistic perspective, it was found that there are three factors that may influence the result of indirect request, which contain the strength of utterance’s illocutionary force, listener’s willingness and pertinence relation between utterance and speaker’s purpose. All the factors will appear when an indirect request is produced, however, there will be at least one of them at the prominent position. This paper partially uncovers how we operate at the cognitive level when indirect requests are delivered.

Keywords: indirect request, force-dynamic patterns, illocutionary force, language processing

Introduction

Since Speech Act Theory was prompted (Austin, 1962), which was further developed by Searl (1969, 1979), indirect request garnered the huge attention from scholars from various perspectives. Indirect request refers to the use of language to deliver a request to the listener(s) in an indirect way. For force-dynamic theory, proposed by Talmy (2000), it is one of the most concepts in the field of cognitive linguistics. For the reason that the conversations are usually indirect, there is a high frequency of implementing indirect request in humans’ daily life. Hence, force-dynamic theory was frequently applied to analysis indirect speech acts.

This paper aims to use Talmy’s Force-Dynamic Theory to explore why different indirect requests may have different complexity to be realized and how the progresses are processed.

Literature Review

According to Searl, the utterance such as “Shall we go to grocery store on foot?” should be regarded as an indirect request, since the request is performed in the form of another mood instead of imperatives. While, it was found that the directive interpretation of indirect request is processed by human beings as fast as that of imperatives (Nicolas et al., 2017), and Alba and Ricardo (2021) challenged the assumption of direct-indirect dichotomy and elaborated that the utterance we mentioned above can be classified into direct request with the help of a processing environment called FunGramKB which is developed based on the cognitively-oriented Construction Grammar view. However, if we focus on the formation of the utterance instead of from cognitive perspective, it is reasonable to assert the assumption of direct-indirect dichotomy, and thus, the conventionalized forms can still be classified as indirect, but in a different (stronger) illocutionary force.

Searl (1975) once classified indirect request into 6 types: (1) the utterance including the listeners’ ability to do something; (2) the utterance including the speaker’s willing to ask the listeners to do something; (3) the utterance including the listeners’ action; (4) the utterance including the listeners’ willing of doing something; (5) the utterance including the reason of doing something; (6) the utterance of one type mentioned above with the embedment of the other. However, this classification of indirect request is not comprehensive, since there is not any principle or standard throughout the whole progress (He, 1988). Soon after, He (1988) proposed another way to classify the indirect request with the consideration of the formation of the utterance, the content of the utterance and context of the conversation. According to He, request, as an illocutionary act, no matter in what way it is conducted, must contain three factors—speakers, listeners, and actions. Hence, indirect request can be classified from the points of these three factors combined with consideration of the formation and content of utterance and context.

However, in our daily life, it can be easily found that sometimes listeners need more time to process such unconventional utterances or even failed to understand speakers’ intention. Though there are different kinds of the classification of indirect request that we mentioned above, the factors that influence process of indirect requests can be various and complicated. Hence, this paper tends to apply Talmy’s Force Dynamic Theory to analyze the process that happens during cases of indirect requests.

Talmy’s Force Dynamic Theory

Force Dynamic Theory was primitively proposed by Leonard Talmy (2000) in the book Toward a Cognitive Semantics where he combined language with knowledge of physics.

According to Talmy (2000), the gist of this theory is that in language formulation there are two entities that lie in the relations of interaction. Just as entities in real world, there are also forces between utterances, such as when one (agonist) offers an invitation to the other (antagonist), s/he also applies a force to the listener. Besides, there are also 4 parameters: (1) the entities mentioned refer to the agonist and the antagonist; (2) the inner force tendency refers to the motion and rest; (3) momentum balance is associated with the stronger and weaker forces; (4) result of the process is motion or rest.

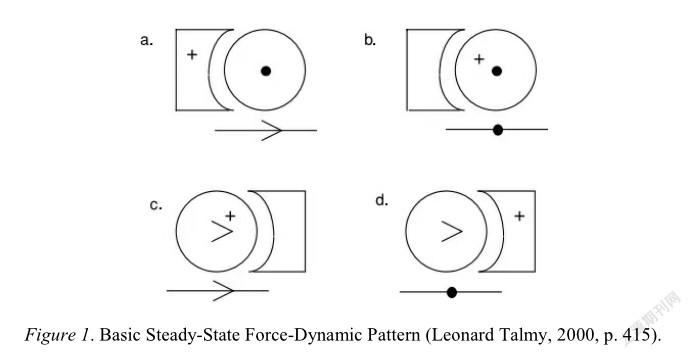

According to Force Dynamic Theory, there are 3 different modes. The one that is the most fundamental is called the basic steady-state force-dynamic pattern with the other two called shifting force-dynamic pattern and secondary steady-state force-dynamic pattern respectively.

Steady-State Force-Dynamic Pattern

Based on Force Dynamic Theory, the utterance of speaker can be viewed as the force coming from the outside, while the listener is regarded as the one who bears the force. Hence, the listener becomes the focal force entity which is called Agonist, and the utterance (or the speaker), called Antagonist, will be the force element that opposes the listener. In any force-dynamic pattern, the Agonist is represented as a circle and the Antagonist as a concave figure.

In Figure 1 (a), the point on the Agonist implies that the Agonist is in the state of rest, and the plus sign refers to a stronger entity, so in such condition, a stronger entity moves an originally static entity to the right. For (b), the originally static entity (Agonist) is still stay static since the force from Antagonist is weaker than that from Agonist, and (c) refers that the Agonist maintains the tendency of moving and moves to the right, since the force from the Antagonist, even though opposing the Agonist, is weaker; in (d), the Agonist that has a tendency of moving to the right becomes static because the force from Antagonist is stronger enough to stop this tendency.

Shifting Force-Dynamic Patterns

This kind of pattern is quite different form the basic one where a new force is added to the Antagonist to make it stronger, weaker, or even disappeared. In (2e), since the force of the Antagonist is not strong enough to move the static Agonist, another force was injected to make the Agonist to the right. In (2f), the force of the Antagonist is not strong enough to stop the Agonist, so another force is added to the Antagonist. In the next pattern, (2g), the original Antagonist that is blocking the Agonist which has a tendency of moving to the right, now is moved by another force and the Agonist can finally be released to manifest its tendency. Correspondingly, in (2h), the Antagonist which is forcing the Agonist to the right is moved away by another force, so the Agonist can come to rest.

Secondary Steady-State Force-Dynamic Patterns

This kind of pattern of secondary steady-state force-dynamic is related to the shifting force-dynamic pattern, while it does not have another force that works on the Antagonist. In the first pattern (i) in Figure 3, there is a stronger Antagonist which is not conducted on the Agonist, so the Agonist can maintain the tendency of motivation and moves to the right. In (3j), since a stronger force does not work on the static Agonist, the Agonist will stay static no matter how strong the force of Antagonist is.

Analyses of Indirect Requests by Force-Dynamic Patterns

In this part, the same indirect request will be analyzed by force-dynamic patterns in different situations where we focus on speaker and listener.

When different utterances are used as same purpose as indirect request, listeners may have different interpretations and give various reactions. For example, suffering in the hot summer, Xin, a teenager who went back home from outside, found the air conditioner wasn’t turned on, and she felt extremely sweaty, so there came the following conversation.

[1] Xin: It is burning hot.

Her father: Yeah. It’s almost 96 ℉ recently, and there’s no rain.

In this case, Xin got sweated and wanted to switch on the air conditioner, however, even though it was a hot day, Xin’s father didn’t turn it on because he wanted to save money. Thus, Xin delivered the utterance to make a statement of her own feeling, trying to suggest her father to turn on the air conditioner. What should be noticed is that there is no utterance with interrogative mood being made to ask the listener’s ability to function as an indirect request, like “Can you turn on the air conditioner, dad?” Instead, she delivered her request in a more polite and acceptable way. However, since there’s no marker in her utterance that refer to the object “air conditioner”, the illocutionary force is relatively not strong enough to reach her aim. On the other hand, her father’s willingness of turning on the air conditioner is not strong enough, so even though Xin’s father got sweated and received some information of Xin’s request, he still hasn’t turned on the air conditioner, which can be represented as the graph (1b) that we introduced above.

However, Xin then added following utterance as another indirect request, and persuaded her father to turn on the air conditioner.

[2] Xin: Dad? You really don’t mind such boiling temperature, right?

Here, since Xin’s father didn’t turn on the air conditioner, Xin delivered another indirect request which adds another force to her father to change his mind. It can be graphed as the picture (2e).

As we can see, when the illocutionary force of Xin’s first utterance was not strong enough, she immediately added another force (indirect request), so that the force of Agonist could be strong enough to move Antagonist. That is to say, after the second utterance of Xin, her father could finally interpret Xin’s request properly and get Xin’s intention. It can be found that utterance’s illocutionary force plays an important role in the progress of processing indirect requests.

While, Xin has another way to persuade his father.

[3] Xin: It won’t be costly even if we turn on the air conditioner.

As we mentioned above, the reason why her father didn’t turn on the air conditioner is that he wanted to save money. Hence, Xin can remove her father’s worrying. This process can be shown as (2g) in shifting force-dynamic pattern.

The Agonist stays static since there’s an obstacle which has an opposite force stronger than Agonist’s tendency. After a force pushed the obstacle away, did Agonist start to move towards right. In this case, Xin’s father was also sweated and had willingness to turn the air conditioner on, however, he worried about bill so he chose not to turn it on. After Xin told him it wouldn’t cost a lot, her father was finally persuaded. In this case, listener’s willingness was under the spotlight of this progress. Xin was trying to remove the worrying of her father and uncover her father’s willingness of turning on the air conditioner.

However, there could be chances that Xin’s father doesn’t give any response to Xin. If Xin says something that has little relation with wanting of turning on the air conditioner or her father cannot really get her intention, then the utterance produced by Xin will be useless. For example:

[4] Xin: Yeah, I even wear my shorts.

In this case, even though Xin emphasized she felt sweated, there’s obvious expression related with air conditioner. Hence, the illocutionary force of this utterance may work in a wrong direction, which means the father in this dialogue can be hard to recognize his daughter’s intention. This process can be shown by force-dynamic pattern (3j).

The Agonist stays static even after a stronger force of Antagonist started, because the force didn’t work on the Agonist. For this utterance, even though Xin’s expression has strong intention to show how sweated she is, it doesn’t manage to let her father turn on the air conditioner, since this utterance doesn’t show a strong intention of that, which means her illocutionary force doesn’t work on the right object, so her father still doesn’t take any action as response. Here, such pertinence relation between utterance and speaker’s purpose also plays a critically key role. When the pertinence relation is weak, even the force of utterance is strong, indirect request can be difficult to accomplish its mission.

According to the analysis, it was found that the utterance’s illocutionary force will influence the reaction of listeners. When the utterance of speaker does not have relatively strong illocutionary force, listeners may stick on their original tendency, even if they get the intention of speaker. Besides, listener’s willingness can be another factor. When listener’s willingness is analogous with speaker’s, s/he is more likely persuaded. Finally, there is also a factor that we call the pertinence relation between utterance and speaker’s purpose. If an utterance barely has pertinence relation with speaker’s purpose, the goal of speaker can be hard achieved. The factors mentioned above will appear as soon as an indirect request is produced, while there will always be at least one factor that play a critical role, which means strengthening one of the factors can facilitate speaker achieve his/her indirect request.

Conclusion

This paper firstly introduced how studies of indirect request developed and how it was classified. However, there are some indirect requests that are hard to be interpreted, and there are also some underlying factors that influence the process. Hence, this paper applied Talmy’s force-dynamic theory to analyze this process from cognitive perspective. It was found that the utterance’s illocutionary force, listener’s willingness and the pertinence relation between utterance and speaker’s purpose are three factors that have influence on the consequence of this process.

References

Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

He, Z. X,. (1988). Indirect requests and classification in English (In Chinese). Journal of Foreign Languages, (04).

Luzondo Oyón, A., & Mairal Usón, R. (2021). (Indirect) requests in Natural Language Processing: a preliminary theoretical proposal. Onomázein, (51).

Ruytenbeek, N., Ostashchenko, E., & Kissine, M. (2017). Indirect request processing, sentence types and illocutionary forces. Journal of Pragmatics, 119, 46-62.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, J. R. (1975). Indirect speech acts. Syntax and Semantics, 3, 59-82.

Searle, J. R. (1979). Metaphor. In A. Ortony (Ed.), Metaphor and thought. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Talmy, L. (2000). Toward a cognitive semantics. Concept structuring systems (Vol. 1). Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press.

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Study on Decorative Patterns of Ceramic Landscape Paintings in Qing Dynasty

- The Chinese-English Translation of Sun Tzu’s Art of War from the Perspective of Bourdieusian Sociology

- Multimodal Discourse Analysis—A Corpus-based Study

- The Media Images of Old Influencers on TikTok:A Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis

- The Desirability of Integrating Chinese Culture into College English Teaching:A Case Study

- Exploration and Reflection on College Online English Teaching in Henan Police College