Reflection:A Critical Look at Escaping Secondary Traumatic Stress Experienced by Law Enforcement Officers

2021-02-19JamesC.Shumpert,FrederickM.G.Evans

James C.Shumpert,Frederick M.G.Evans

Despite the stigma that is associated with law enforcement officers receiving mental health resources and treatment to combat secondary traumatic stress, it is widely the most effective form for recovery and having a fulfilling career. Law enforcement officers are superheroes and, they are known for saving the day. That is why it is critical for mental health offerings to be normalized in law enforcement agencies and constant evaluation of the psychological and cognitive well-being of officers. Unfortunately, the stress of the profession will not go away, but having resources and incentives to address several factors that officers face will assist with their overall feeling about the important work they do. As such, it is recommended that law enforcement agencies adopt programs to treat secondary traumatic stress, such as Critical Incident Stress Debriefing, Peer-Support Program, and Crisis Intervention Team. While there is no perfect program, these programs are designed to reduce the risk of serious injury or death during an emergency interaction between citizens and law enforcement officers. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of those charged with protecting law enforcement officers to understand the stress and how it affects the mind and body of those officers in managing life, work, and citizens.

Keywords: secondary traumatic stress, mental health, stress, critical incident stress, crisis intervention

Overview

In todays civilized society, policing requires more presence than it did during the Wild West. There is no questioning the fact the law enforcement officers help to protect and serve the community, and without them, our daily lives would be threatened. According to the Gramlich (2020) PEW Research that tracks the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) crime statistics, there are 2,109.9 property crimes per 100,000 people, compared with 379.4 violent crimes per 100,000 people. While one is more significant, there is a high cost mentally and physically on the lives of law enforcers that often lead to added harmful stress. Accordingly, Selye (1950), founder of the stress theory and the general adaptation syndrome theory, stress contributes to every disease known to man. Selve maintains that failing to address stressors could produce diseases of adaptation.

Research on the harmful effects of stressors on police officers found that 74% reported recurring memories of incidents, 62% experienced recurring thoughts or images, and 47% experienced flashbacks (Conn, 2016). Such stressors are considered linked to secondary traumatic stress disorder are believed to be a threat to the psychological well-being of law enforcers. The weightiness of stressors that law enforcement officers face is oftentimes hard to cognize and conceptualize. According to research endorsed by the US Department of Health and Human Services, secondary traumatic stress is a disorder associated with compassion fatigue, a natural but disruptive by-product of working with traumatized clients. Further, secondary traumatic stress is a set of observable reactions to working with people who have been traumatized and mirrors the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (Osofsky et al., 2008).

In a study conducted by Quieros (2013) and his team, they posit that policing as an occupation was not only stressful, but more importantly, impactful on police officers mental and physical health, performance, and interactions with citizens. Quieros et al. (2013) research and others with similar results are troubling because inevitably first responders are exposed to circumstances and incidents of a critical nature. Such occurrences can evoke adverse emotional reactions and affects their job performance, health, decision-making, and family life. Being aware of the effects some crimes have on the lives of officers while understanding the need for the services of law enforcement cannot be ignored. As such, measures must be identified and put in place that recognizes the potentially detrimental effects of stress-induced by traumatic incidents. Research suggests that such health issues can be dealt with successfully when identified early and referred to the appropriate care (Chiappo-West, 2017). The purpose of this reserach is to identify and draw a conclusion on the impact of work-related stress and its outcome on law enforcement officers.

Work Stressors

The dangers associated with protecting the lives of citizens, unfortunately, added stress to the lives of law enforcement officers beyond the workday. Selyes (1974) classic The Stress of Life describes the effect of long-term environmental threats he calls “stressors.” He maintains that the unrelieved effort to cope with stressors can lead to heart disease, high blood pressure, ulcers, digestive disorders, and headaches (Selye, 1976). According to Selye, stressors in police work fall into four categories: (a) inherent, (b) practices and policies; (c) externally from the criminal justice system and the society at large; and (d) internally from within individual officers. Several sources of police work stressors have been identified and involve danger and job risk, administrative organization, and lack of organizational support (Violanti et al., 2017).

In an article written for high-powered leaders, four types of stress were identified for those who are managing big businesses: time stress, anticipatory stress, situational stress, and encounter stress (Albrecht, 1979). While those stressors were identified to help leaders determine their major cause of stress, law enforcement officers would be faced with all of these in one situation. Encountering stressful occurrences are the nature of the job and expectations inherent in police work.

Stress Inherent in Police Work

Scenario 1:

911: What is your emergency?

Caller: Hi. I hear a noise in the alley. It may be a cat, but it has been whining for a while and I cant sleep. Can you send a police officer?

911: We will send someone out there. What are your name and address?

(Less than five minutes later they were at the scene).

Two police officers arrived at the scene. Together they entered a dimly lit back alley with their flashlights shining high and low for signs of trouble. The smell of spoiled food and urine was almost overpowering. Both had walked this beat many times, yet tonight something seemed different. Instinctively, both withdrew their weapons with the skill of a synchronized swimmer. As they cautiously move toward the back of the alley, they could vaguely hear a sound. Officer Moses recalled that it did not sound like that of a cat. The moaning sound was coming from the backside of a large trash container. The cry for help was barely louder than a whisper. Officer Clarkequickly directs her flashlight in the direction of the container. The beat of her heart stops upon seeing a young child 10 or 11 years old, crouched in a ball with a t-shirt hanging around her neck. She laid helplessly on a stained cardboard box barely audible echoing the words “stop, stop, stop, stop, …” continuously. Before either officer can reach the child, a man jumps from the other side of the container and lunges at Officer Moses with a broken beer bottle. Officer Clarketurns only to see the man stabbing his partner. He fires one shot, and the man goes down.

The event does not end there. Many would ask, “What happened to the child?” “What happened to officer Moses?” Yet few would think to ask, “What happened to Officer Clarke?” Officer Clarke, during the final seconds of this scenario, was faced with time stress, anticipatory stress, situational stress, and encounter stress. The job of police officers working a daily beat can be multiple times stressful than that of a CEO due to the stress inherent in the work that they do daily. In this scenario, instant decisions were made without the luxury of consultation. Imagine the psychological affects any part of this would have on both officers.

Police officers are faced witha volatile situation that can escalate from one stressful situation to even higher demands in their work. Stress from the unknown often when officers stumble on a crime and are the first to approach victims. In this scenario, Officer Clarke at a moments noticewas torn between helping the victim, helping his partner, restraining the suspect, or calling for backup. The scenario suggests that police officers encounter events or conditions considered highly stressful. The results are consistent with research where chronic exposure to stressors is associated with secondary traumatic stress (Chiappo-West, 2017).

Alarmingly enough, these stressors occur at a higher and increased rate depending on the nature of the calls to crime scenes. For example, an officer who continually is exposed to seeing violent crimes such as homicide may be at greater risk for psychological and secondary stress trauma.This scenario points to stressors inherent in police work that is consistent with stressful workplace exposures and the impact on the mental and physical well-being of officers (Violantiet al., 2017). Much of what is inherent in workplace stressors for officers can be linked to policies and practices on the police force.

Policies, Practices and Workplace Stress

Inherent to police work is the daily practice of extremely stressful conditions in often higher occurrences than most other occupations (Jaramillo et al., 2005). Policies and practices are created to ensure the safety of officers in doing their jobs to avoid such inherent stressors. Policies generate the foundation for all functions in law enforcement. From law enforcement interactions to operational standards, policies are designed to guide and protect the officers in upholding the law while fulfilling their jobs (Cunningham, 2020). Whereas the practices in law enforcement are carefully crafted due to the nature of police work to provide practical steps and safety measures for carrying out the policies. Conducting the business of the law without proper training will set police up for failure. Instituting and employing sound policy is a critical part of training police officers to making sound decisions in critical situations.

Satula and Sparger (2020) reviewed a study on the importance of the law enforcement procedures manual. They theorized the importance of both policy and procedures for police officers to conduct their work. They maintained that policies without carefully designed and implemented procedures will lead to ineffectiveactions.“Policies set the expectation and procedures outline how the expectation will be met” (Satula & Sparger, 2020, p. 1). While procedures can differ between agencies, they require immense attention to detail to ensure they are properly implemented, thus avoiding undue stress to workplace situations.

Systemically, community policing emphasizes the need for police departments to restructure and rebuild their relationship within communities. Stressors are attached to law enforcement officers from multiply perspectives as it relates to how they interact with the community. Based on the revelations of numerous current and past events, stressful situations are being realized in unlawful and lawful situations as to how and why certain events are happening (Solomon, 2016). The case of George Floyd is just one example of many that police are dealing with internally and publicly that accounts for undue stress. Such situations require police officers to modify their attitudes, biases, and behaviors toward citizens and policing practices (Mentel, 2012). At the foundation of community policing is the belief that the efficacy of police departments can be improved significantly by increased engagement with citizens, as well as include in their efforts to eradicate crime thoughtful analyses of the precipitating causes of the offenses (Braga, 2015). Hence, the concept of community policing encompasses two complementary core components: community partnership and problem-solving (Irwin& Pearl, 2020).

While this might seem like an easy feat for law enforcement officers to build partnerships and problem solve, it takes an emotional toll on officers, especially with the present climate with injustices to the community by some law enforcement officers (Irwin & Pearl, 2020). Often time law enforcement officers are not receiving counseling, debriefing, and /or some other treatment to help with the relief of symptoms or coping skills to deal with these stressors. As aforementioned, it is challenging for them to execute their duties appropriately. This is not evidenced to prove community policing does not work, this example is only to highlight the one program that may increase stress for law enforcement officers.

Several personal attributes have been associated with stress-reactivity. Anshel (2000) found officers who maintained increasedistrust, pessimism, hardness, and persistence were more prone to higher levels of stress. Much of these behaviors are linked to perceived control andconnectedto an inability to resist stress. Regardless of the source of the stressor, once a situation is perceived as threatening or challenging, law enforcement officers and encountering some form of stress, and in most cases, it is secondary traumatic stress.

Secondary Traumatic Stress

Scenario 2: Two rural police were conducting regular policing of an area in a neighborhood subdivision. Upon arrival, they noticed a vehicle parked in the middle of the roadway. When we exit the patrol car, Officer Tanny asked the young lady why she was parked in the street. She replied, “My boyfriend has my keys.” They headed toward the house that she indicated the boyfriend was inside. As they walked toward the house, Officer Green advised the crowd of 5 or 6 individuals standing by a fire in the yard of an abandoned house to leave the premises. All but one of the men walked toward the road away from the yard. Officer Green noticed this individual was making his way to the porch of the abandoned house. By this time, two additional deputies pulled up and spoke to the young lady that was still in the vehicle. Unbeknown to Tanner and Green, the additional deputies were responding to a possible kidnapping. After an officer spoke to the lady, he casually walked over to Tanner and Green and advised them that girl was being held against her will. Deputy Green was sure it was the man who had just entered the abandoned house. that the boyfriend as the same individual was making his way to the porch had kidnapped her. At this time, Green revealed that he knew from another incident and felt he would be able to apprehend the suspect. As the deputy turns to walk toward the abandoned house and up the stairs, his mouth is dry, his heart feels as if it will pop out his chest, his head begins to ache, and tension mounts in his shoulders. As he walks, his breathing is labored, and sweat breaks out all over his body. Before Deputy Green get to the door, his body is preparing for what may lie ahead, and the dangers that may lie ahead. When he pushes open the door, he finds the man hanging from a rope in the center of the room.

Initially, Deputy Green was experiencing a critical incident situationthat is inherent in a high-risk situation. The body tends to transition into multiple stages when entering a situation that may be harmful and risky that require quick decisions to be made (Andersen & Gustafsberg, 2016)

McCarty (2016) refers to Greens behaviors before pushing open the door as the fight-or-flight response. The fight-or-flight response was developed by Cannon when he studied the secretion of epinephrine from the adrenal gland of lab animals. Selye (1974) proposed three universal stages of coping with a stressor, one of which is the fight-or-flight response, in addition to the general adaptation syndrome, and alarm reaction. Once he opened the door the shock of the experience changed to secondary traumatic stresswhich usually happened to officers when facing disturbing images.

The job of a law enforcement officer at any level has been widely recognized as being inherently stressful(Skogstad et al., 2013). However, those who serve in that capacity are excepting of the exposure to trauma as an occupational hazard and with limited preventive measures to the exposure to traumatic events (Birch et al., 2017). Figure 1 provides a list of varied outcomes that can happen from secondary traumatic stress over a period. These perceived outcomes impair law enforcement officers from being able to fully carry their duties and assignments with fidelity.

For this article, the concept of “secondary traumatic stress” is defined by Bride and Kintzle (2011) as “Secondary traumatic stress refers to the occurrence of posttraumatic stress symptoms following indirect exposure to traumatic events” (p. 22). Having a vocabulary of those outcomes will demonstrate how secondary traumatic stress can impact a law enforcement officer. Law enforcement officers are commonly well-known for executing esteemed and distinctive meaning within todays society. Because of the style of their work, they are susceptible to facing incomparable types and high intensities of stress than any other profession. Law enforcement officers under these stressful conditions may manifest secondary traumatic stress. Furthermore, being exposed to excessive and inapt use job-related stress, which ultimately results in an adverse impact upon the community, many officers tend to become burned-out in their perceptions, which negatively affecting themselves, their families, and the performance of service to the community.

Cause/Effects

The mental health decline for untreated stress in law enforcement (like many in the helping profession) grows great concern. In the United States, two-thirds of officers involved in shootings suffer intermediate or rigorous problems, with about 70% deciding to leave the profession within seven years of the incident. Police are readily admitted to hospitals at considerably higher rates than the general population and rank third amongst occupations in early death rates (Sewell et al, 1988). Interestingly, however, despite the rate of divorces among police marriages, there is no evidence for a disproportionately high divorce rate (P1 First Person, 2020). One recent police event associated with both divorce and suicide happened recently in Lafayette Parish, New Orleans. On February 1, 2021, Deputy Clyde Kerr III took his own life Monday outside the Lafayette Parish Sheriffs Office (Gagliano, 2021). He left these haunting final words in a series of social media videos.

In Kerrs videos, he talked directly to the camera on a range of issues, from police brutality against Black people and mental health needs in policing, to division in society and childrens exposure to murder, violence, and other negative or traumatic influences. He also describes his struggle to reconcile his identity as a Black man with his profession while hinting at his impending suicide. … The videos show a man who professed he was upset by the state of society: “Ive had enough.” (Gagliano, 2021, p. 1)

Perhaps the most tragic form of police casualty is suicide (De Similien & Okorafor, 2017).

Twice as many officers, approximately 300 annually, die by their hand. These startling statistics lead one to ask the question, what best practices are in place to help treat secondary traumatic stress in law enforcement officers? Although law enforcement officers at times work in concert with mental health professionals, there is still a vulnerability and mistrust that law enforcement officers have with the stigma of receiving mental health services for what they are facing. Many fear that the disclosure of how data/reports will be used will adversely impact their career long-term. Despite the discomfort in speaking with mental health professionals, some agencies have created opportunities for officers to combat secondary traumatic stress in police officers.

Combating Secondary Traumatic Stress

As crises and tragedies become prevalent, the need for effective crisis response resources becomes apparent for addressing stressors. Combating secondary traumatic stress must be tackled if those charged with protecting the lives of citizens will continue as law enforcement officers. For those in crisis or who know someone in crisis, there are numerous resources available. The Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act was signed into law in January 2018, recognizing that law enforcement agencies need and deserve support in their ongoing efforts to protect the mental health and well-being of their employees. Good mental and psychological health is just as essential as good physical health for law enforcement officers to be effective in keeping our country and our communities safe from crime and violence (Violanti et al., 2017).

Under the Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act, resources were designed to help officers immediately after this have experienced some sort of trauma. One resource for immediate help is the Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) (Harrison et al., 2014; Mitchell & Everly, 2001). Another resource is designed to provide help via peer support. Peer-support has been widely accepted as a confidential outlet for police officers to speak to other police officers free from judgment and the sharing of private information. Another resource that is used to help with the de-escalation of stress is Crisis Intervention Training embedded with support for mental health treatment. Although mental health has been traditionally frowned upon by officers, more and more are seeking mental health services.

Critical Incident Stress Debriefing

Critical incident stress debriefing was developed as a therapeutic technique to be used with first responders after exposure to an excessively stressful or horrific critical incident, the primary goal being to facilitate adaptive coping mechanisms following the critical incident. (Burchill, 2019, p. 1)

Combating secondary traumatic stress requires immediate action and attention to the officers in dealing with traumatic incidences. Critical Incident Stress Debriefing (CISD) is designed to monitor the effects on officerslivelihoodto begin the restorative process for the traumatized sufferers. There is little doubt that law officers who witness or participate in a traumatic incident may experience psychological effects that hinder their ability to work effectively and add pressure on their family life (Mitchell & Everly, 2001). Thus, the traumatic experiences prohibit their ability to experience pleasure in their professional or personal life (Harrison, Lawton, & Stewart, 2014). CISD is a formed interference designed to promote the emotional processing of traumatic events through the airing and normalization of reactions, as well as a precaution for possible future experiences (Mitchell & Everly, 2001).

Comprehensive thought has been included in the structure for the CISD program. The trauma team is comprised of at least one mental health specialist, one or more work-related peers, and a trained CISD emergency service worker. The 2-to-3-hour single group process occurs 24 to 72 hours after the critical incident (Anderson et al., 2020). Anderson and others maintained that CISD is a necessary technique connected with efficient and effective management of current and future stress.

In most situations, CISD is a component of the Critical Incident Stress Management (CISM), a multi-component intervention system (Barboza, 2005). While this intervention has been used extensively following traumatic events, its efficacy is under much debate (Bledsoe, 2003; Cannon et al., 2003). Presently, there is a controversy as to whether it helps with initial distress and if it does prevent post-traumatic symptoms(Barboza, 2005). While CISD and CISM maybe meeting some of the needs of law enforcement organizations, numerous studies show adverse effects or little to no release of traumatic stress disorders (Brewin et al., 2000; Howell, 2016). Theoretically, CISD and CISM might sound powerful and humane, but some studies contend that it lacks empirical support that utilizing the approach reduces psychological illness caused by the trauma (Barboza, 2005). Yet, some studies support the use of CISD and CISM, since many officers maintain the process was helpful (Everly et al., 2000).

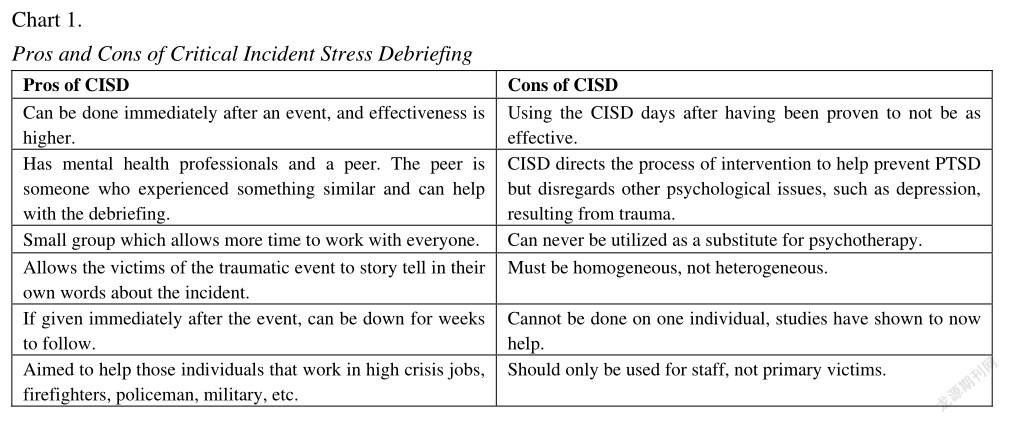

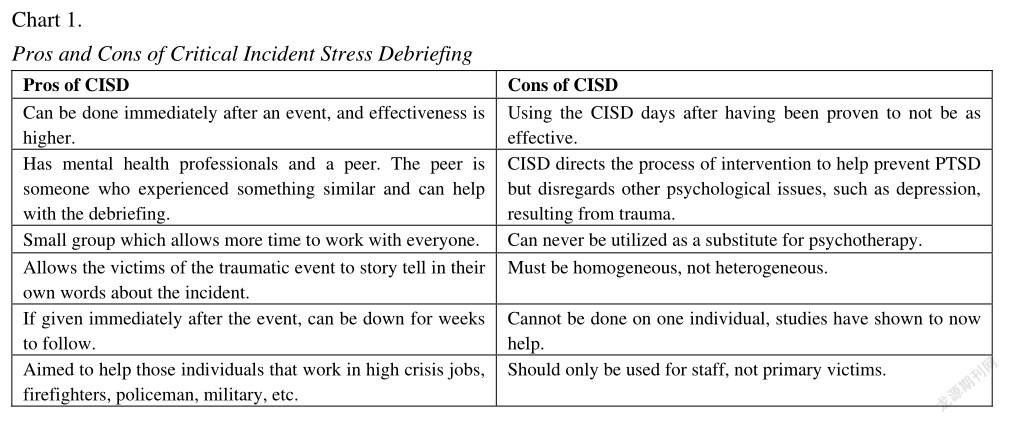

Based on the research conducted for this article, it is recommended that law enforcement organizations do continue research when considering CISD and any other programs for law enforcement officers who have experienced traumatic events on and off the job (Everly et al., 2000). Barboza (2005) examined the CISD approach and created a chart outlining the pros and cons regarding the efficacy (Chart 1). The information was compiled based on critical incidents for stress debriefing (Davis, 2004; Mitchell, 2003).

Peer-Support Program

Peer-support, a process used to combat secondary traumatic stress, provides police officers with an opportunity to share their experiences with other officers. This process is considered important since fellow officers are perhaps best able to relate to their colleagues experiences in the line of duty. Peer-support has been widely accepted as a confidential outlet for law enforcement officers to speak to other officers free from judgment. Further, the process helps officers with empowerment and self-efficacy (Burke et al., 2018). Further, officers working with peers have found limited effects of internalizing stigma. The peer-support program provides officers an outlet that lets them know they have others who understand the circumstances because they have been in similar situations (Creamer et al., 2012). Promoting the sense that police officers are not alone and encouraging the idea that there is no shame in seeking help both contribute significantly to bringing about changes in the current criminal justice culture.

In the law enforcement workplace, peer-support is about officers helping one another through confidential discussions. Without the utilization of peer-support, the mental health of officers problems can affect their job performance and, ultimately decrease their ability to function (Milliard, 2020). The main objective of a peer-support program is to resolve employee and workplace problems before they escalate to crisis levels by providing an extra network of support in the workplace (Wallace, 2016).

In Ontario Canada, the police department created a peer support program due to the elevated levels of suicide and other mental health issues seen within the police force (Milliard, 2020). However, the peer support program was not implemented until the department conducted a study to ascertain information on the overall effectiveness of peer-support programs on police officers mental health (Milliard, 2020). The police department in Canada thoroughly examined the Mental Health Commission of Canada Peer-Support Guidelines and a National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace Guidelines but determined that neither plan embraced support for first responders. The department created its police peer-support programs to address the “safety-sensitive” positions police officers encountered (Weible &Sabatier, 2018).

The Canadian Police Departments peer support program was highlighted to share their strategy for creating a program that was specific to meet their needs. The other programs were used as guides but did not have the required component necessary to address the traumatic experiences that police officers in their area faced. The intent of this article is for each law enforcement agency to do their due diligence in finding the program that is best for those officers having secondary traumatic stress.

Crisis Intervention Team

There has been an increase in mental health crisis services across the United States. However, according to the National Alliance of Mental Illness (2020), the available services have not sufficiently addressed the need for law enforcement officers serving as first responders to most crises. In Memphis, TN, the fatal shooting of a man suffering a mental health crisis by a police officer led to the creation of the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) to improve safety in police encounters (Rogers et al., 2019). Therefore, the CIT program that currently operates in more than 2,700 communities was created as a community-based approach to link the services of law enforcement, mental health providers, hospital emergency services, individuals with mental illness, and families of the mentally ill. The CIT model provides a greater understanding of the nature of mental health issues and provides a way to better understand the culture of law enforcement agencies. When officers know and recognize the indicators or warning signs associated with mental illness, they can prevent an impending crisis by utilizing skills to talk to someone with mental illness, thus saving lives and themselves from undue stress (Watsonet al., 2008).

Studies and extensive research have been conducted to explore interventions within mental health and the criminal justice fields because of the national attention given to mental illness and fatalities (Rogers et al., 2019). In 2018, in the United States, there were more than 1,000 police fatalities of which, 25% were those suffering from mental illness (Saleh et al., 2018). Studies have found little significant difference between CIT-trained officers and untrained officers in terms of the diversion to emergency services for certain psychological illnesses, while other studies have shown a consistent reduction in the risk of death during emergency police interactions(Taheri, 2016). Examining the literature and research studies specific to the goal set by individual police agencies will avoid disappointments when implementing a program targeted to meet a special need.

Conclusion

Conducting extensive literature reviews and examining several studies provided context as to why local law enforcement agencies must do their due diligence in delivering support and resources to combat secondary traumatic stress within law enforcement. While few agencies conduct the research necessary in identifying the program specific to their needs, it is recommended that agencies examine the process used by the Canadian Police to determine what issues need to be addressed before adopting a one size fits all model. Finally, it is imperative to create a provincial mental health standard, or, at the very least, to provide guidelines for peer-support in police organizations, again like that of the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) in Ontario, Canada. There, they supported the creation of peer-support guidelines to ensure best practices and a level of risk management.

References

Albrecht, K. (1979). Stress and the manager. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/135050767901000316?journalCode=mlqa

Anderson, G. S., Di Nota, P. M., Groll, D., & Carleton, R. N. (2020). Peer support and crisis-focused psychological interventions designed to mitigate post-traumatic stress injuries among public safety and frontline healthcare personnel: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7645. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33092146/doi: 10.3390/ijerph17207645. PMID: 33092146; PMCID: PMC7589693.

Andersen, J. P., & Gustafsberg, H. (2016). A training method to improve police use of force decision making: A randomized controlled trial. SAGE Open, 6(2), 215824401663870. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016638708

Anshel, M. H. (2000). A conceptual model and implications for coping with stressful events in police work. Criminal Justice and Behavior. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0093854800027003006

Barboza, K. (2005). Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD): Efficacy in question. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 3(2), 49-68.

Birch, P., Vickers, M. H., & Kennedy, M. (2017).Wellbeing, occupational justice and police practice: An “affirming environment”? Police Practice and Research, 18(1),

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- Overlapping or Reshaping:Chinese Image in Lin Yutang’s Trans-creation Works

- The Contribution of Blended Teaching Approach to the Promotion of Learner Autonomy

- A Corpus-based Study on the Existing Comments of the Literature Works:Hemingway’s A Clean,Well-Lighted Place

- The Female Dilemma in The Grass Is Singing

- An Analysis of the Relation Between Phase,Situation and Aspect Suffix“LE”in Chinese

- Study on Chinese“Internet New Idioms”