Cultural Orientations of ELT:The Perspectives of Chinese EFL Students and Teachers

2021-02-19LIUJun-shuan

LIU Jun-shuan

This paper reports on part of the findings of a study that explores the perceptions of Chinese ELT stakeholders on native speakerist practices in ELT. Data related to this paper were collected through questionnaire surveys of 817 Chinese EFL students and 26 Chinese EFL teachers, of whom 26 students and 14 teachers attended follow-up interviews. Data analysis via a critical lens suggests that the majority of the participants uphold Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English and the reference model of ELT. These suggest the continuity of native speakerist ideology in Chinas EFL education. Future studies are expected in view of the finding that an unneglectable proportion of the participants maintain a neutral stance on these issues.

Keywords: cultural bedrock of English, cultural reference, cultural threat; students, teachers, ELT in China

Introduction

The conventional English Language Teaching (ELT) expects learners not only to acquire native speaker (NS) linguistic norms, but also to acculturate into NS culture (Baker, 2011; Dewey, 2015; Rose & Galloway, 2019). However, the global expansion of English in history and particularly over the past few decades has given birth to many English varieties, changing the ownership of English and its cultural base, which have been granted to Inner Circle countries (Kachru, 1985), and demanding an epistemic break from the traditional native speakerist ELT practice (Kumaravadivelu, 2012). In addition, a limited number of studies have been found to explore how ELT stakeholders perceive cultural orientations of ELT (see liu & Li, 2019). In light of this situation, as well as the current gigantic size of Chinas ELT industry, a large-scale study was conducted on the perceptions of three groups of Chinese ELT stakeholders—students, teachers and EFL program administrators—on native speakerist practices in China. This paper will report on part of the findings, i.e., the views of Chinese EFL students and teachers about cultural orientations of ELT in line with the following three questions.

(1) How do Chinese EFL students and teachers think about the cultural bedrock of the English language in the current era of English globalization?

(2) What culture(s) do they expect to teach or learn as the reference model(s) in teaching or learning English?

Methods

Data pertainning to this article were gathered through questionniare surveys with Chinese EFL students (817) and teachers (64), and through semi-structured interviews with 26 students and 14 teachers sampled from those questionnaire participants. When the study was conducted, allof the participants were engaged in College English education—an EFL program for non-English-major undergraduate students in China. The students come from different disciplinary areas; the teachers are different in professional title, academic degree, and length of work. All of these factors contribute to the representativeness of the participants.

Two questionnaires and two sets of interveiw questions were designed for students and teachers. One multi-item scale of each questionnaire, as well as three items in each set of interview questions, are aimed at soliciting the opinions of the students and teachers on cultural orientations of ELT. The questionniare survey for students were conducted in class while that for teachers was operated through email. The interviews were conducted individually via face-to-face conversation and email exchange at the convenience of the participants.

The mean, percentage and frequency of the multi-item scale were calculated to assess the overall cultural orientation tendency of the students and teachers. Attention was also paid to statistical values of individual question items. After the descriptive analysis, an Independent Samples t-test was conducted to explore the mean difference between the two participant groups. In the meantime, the effect size in the line with Cohens d was calculated to assess the magnitude of the mean difference. The assessment followed Cohens criteria that propose 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 as the numeric representation of small, medium and large effects respectively.

The interview data were analyzed through the approach of critical discourse studies (CDS; see van Dijk, 2008), coupled with thematic analysis method (Bryman, 2012, pp. 580-581). Specifically, the interview transcripts are dividedinto broad thematic groups in reference to research questions and the traditional Self versus Other ideology in applied linguistics and ELT; those classified were then categorized into sub-thematic cohorts, which were further assorted into smaller thematic clusters. In this process, I sought high-frequency remarks that either support or counter the conventional native speakerist cultural orientation of ELT, and attempted to interpret and explain these remarks in reference to the social, historical and political contexts surrounding global ELT, particularly EFL education in China. Presented as follows are how the students and teachers perceive cultural bedrock of English, cultural reference of ELT, and the cultural oppression or discrimination discourse.

Findings

Opinions on Inner Circle Culture as the Bedrock of the English Language

Data collected from the multi-item scale in the questionnaire for students (see Table 1) indicates that the majority of the student participants are trapped in the conventional native speakerist ideology concerning the cultural basis of English. This is evident from the mean for the four question items (3.48±0.802) as well as the average total percentage (51.4%) for the students in (strong) support of Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English. The pro-nativenesspsyche is most visible from the responses to Item 1, which gains support from 60.2% of the students. However, this mentality seemed to decrease when Outer and Expanding Circle cultures are mentioned, as can be inferred from the statistics for the stances of the students on the other three Likert scale statements, particularly Item 3. Notably, an average of 39.0% of the students selected the “Not sure” answer, an interesting finding that warrants further study.

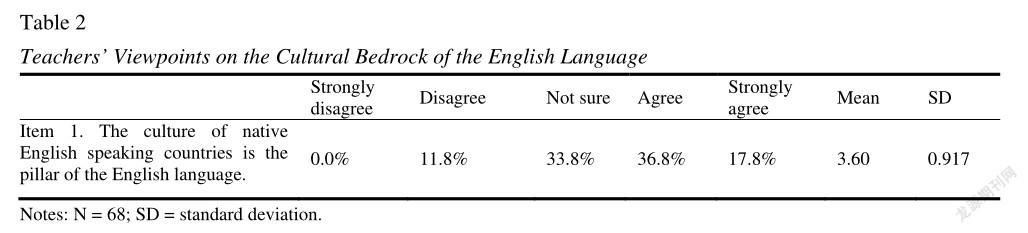

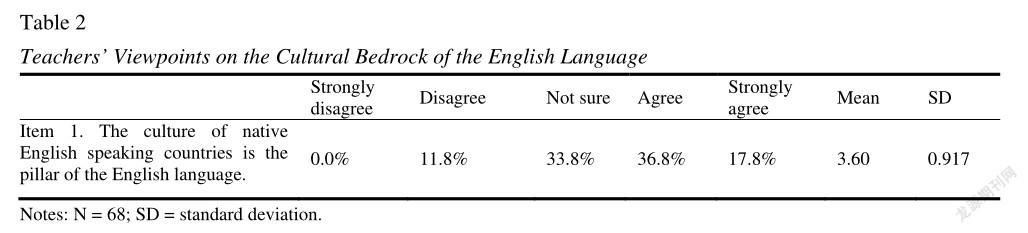

Data collected from Item 1 in the questionnaire for teachers (see Table 2) indicate that most teachers also bought into the conventional native speakerist ideology regarding the cultural basis of English, as can be inferred from the mean (3.60±0.917) and the percentage (54.6%) for the teachers who expressed (strong) agreement on the Likert scale statement. It is noted that no one expressed strong disagreement, but 33.8% of the teachers chose the “Not sure” answer.

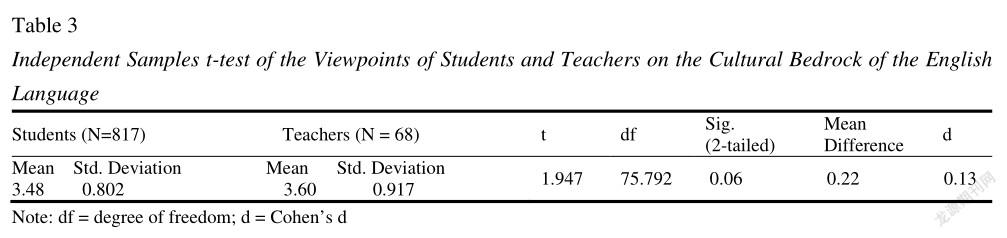

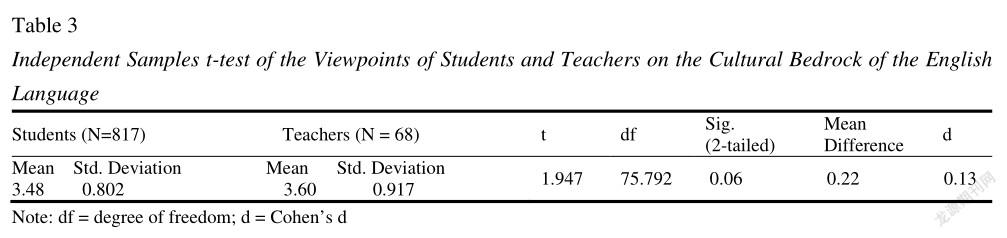

Despite the intergroup similarity, the difference in average mean between the students (3.48±0.802) and the teachers (3.60±0.917) seems to indicate a discrepancy in degree to which the two groups identified with Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English. However, the results of the Independent Samples t-test (see Table 3) suggest that the numerical disparity is of no statistical significance (p > 0.05; d = 0.13).

The interviews with the students and teachers also indicate a strong pro-nativenessmindset. 88.5% (23) of the 26 student interviewees regarded it as a given that Inner Circle culture serves as the pillar of English, as is represented by the unmodified predicates as well as the matter-of-fact statements, such as those initiated by “It is well known” and “It is natural” (Student-12). In justifying their stance, they frequently utilized metaphorical words that convey a sense of historical validity, such as “origin”, “source” or “root” to describe Inner Circle countries in relation to the English language. Furthermore, they attempted to seek proof from the traditional well-established anthropological episteme on the inseparability between languages and culture (see Brown, 1994, p. 165). As Student-12 put it,

It is well known that English originated from Britain and further developed in other native English-speaking countries. Since language cannot be separated from culture, they are a unity, [and] it is natural that English is rooted in the culture of those countries. (Student-12; Emphasis added)

Similar discursive strategies and linguistic forms are apparent in the perceptionsof 71.4% (10) of the 14 teacher interviewees on the relationship between NS culture and English. In the exemplifying excerpt below, the episteme on the language-culture inseparability is also adopted as a given, from which Teacher-8 started to elaborate on her support of Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English.

Since language is entwined with culture, of course, English is deeply rooted in native English-speaking countries, particularly Britain or America. English originated from these countries … it represents their social, political, economic culture [and] the everyday life of people living in these countries. Therefore, these countries are the soil where English grows and develops. (Teacher-8; Emphasis added).

Observed from these excerpts, the overarching logic followed by the students and teachers resonates with the traditional essentialist view on the nation-language-culture trinity (Anderson, 2006). To be specific, English derives from Inner Circle countries, which have their own culture; the inseparability between language and culture makes Inner Circle culture the natural bedrock of English. In this sense,this finding, in tandem with the statistical discoveries, reinforces to a great degree the traditional polarization of NS and nonnative speaker (NNS) cultures in relation to the English language (Kumaravadivelu, 2012; Mckay, 2012).

Viewpoints on Inner Circle Culture as the Reference Model in Learning English

In the questionnaire for students, Items 5-6 were intended to investigate the viewpoints of the students in relation towhose Circle culture serving as the point of reference in learning English. According to the statistics reported in the Table 4, an overall pro-nativeness ideology was found prevailing within the student group. Supportive of this ideology is the average mean (3.58±0.970) for this question cluster and the average total percentage (66.4%) for the students who are convinced that one should take the sociolinguistic or pragmatic norms of NSs as the point of reference in learning English. For these students, it seems that learners of English would only contact Inner Circle NS in the future. Notably, only 9.3% of the students expressed oppositions, but about one-fourth (24.3%) of the students selected the “Not sure” answer.

The perceptions of the teacher participants on this rhetoric are also observable from their responses to two Likert scale statementsin the questionnaire for teachers (Items 2 and 3).

Data presented in Table 5displaya strong pro-nativeness stance among the teachers, as is evident from the average mean (3.62±0.916) for these two questions as well as the average total percentage (63.3%) for the teachers in (strong) support of adhering to NS cultural norms. Interestingly, 29.3% of the teachers displayed a“Not sure” stance.

Observed from Tables 4 and 5, a similar pro-nativeness attitudinal tendency seemed to exist among the students and teachers. This is confirmed by the results of the Independent Samples t-test (Table 6), which suggest that the statistical difference in mean between these two groups bears no statistical significance (p > 0.05; d = 0.02).

The pro-nativeness mindset among the students and teachers is more evident from interview data. Specifically, all of the 26 student interviewees and 14 teachers considered it normative to lay emphasis on learning Inner Circle culture.

When justifying this viewpoint, most of the student interviewees developed their arguments in line with the logic of rationality and altruism (see van Leeuwen & Wodak, 1999). On the one hand, they resorted to the well-established anthropological episteme, namely, language is inseparable from culture, as they did in arguing for their support of Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English. On the other hand, they claimed that a good knowledge of Inner Circle culture is beneficial for students to learn English. In other words, to learn Inner Circle culture is a rational act because English is rooted in Inner Circle culture; to take it as the reference model can bring benefits to students because it can deepen their understandings of the English language. Following this line of thoughts, it seems necessary to take Inner Circle culture as the reference. In addition, those students presented their arguments in a state-of-the-fact manner, which is represented in the modal word, “must”, and the auxiliary word, “will”, that predicts the undesirable learning results. As Student-26 put it,

To learn a language, you must learn its culture. Otherwise, your knowledge of the language will be like the water without a source or a tree without a root, and you will not be able to understand the connotation of the language. You will only know the how without knowing the why. This is a great pity for language learners. (Student-26; Emphasis added)

Most of the teacher interviewees also justifiestheir standpoints from these two perspectives. In addition to acquiring the English language, 50% (7) of the 14 teachers claimed that a good knowledge of Inner Circle culture is conducive for English learners to develop intercultural competence and minimize the chances of “cultural shocks” (Teacher-7) and communicative breakdowns. It seems that those teachers forget the role of L1 culture in facilitating intercultural communications (see Savignon & Wang, 2003). In the words of TI-2,

Language is a special social and cultural phenomenon. It becomes conventionalized through peoples long-term social practices … Each language is produced and developed in a particular social and historical context … each language reflects the cultural phenomenon that is unique to the countries or nations that use the language in specific social environments and historical phases. The lack of background knowledge and cultural awareness will easily lead to breakdowns in language communication. (TI-2; Emphasis added)

Observed from this excerpt as well as the others in this subsection, the two groups of interviewees as a whole agreed on taking Inner Circle culture as the reference model in learning English. This attitudinal tendency, in tandem with the statistical findings resonates, to a great degree, with the traditional monocultural tenet in ELT, namely, learners need to acculturate to L2 culture or acquire L2 linguacultural norms (Schumann, 1986). It seems that most of the participant did not realize or refuse the accept the current globalization of the English language, resulting in the reinforcement of the hegemony of Inner Circle culture within ELT and beyond.

Discussion

This article explores the viewpoints of two groups of ELT stakeholders on cultural orientations of ELT in China, in addition to intergroup attitudinal (dis)similarities. As regards the relation between Inner Circle culture and English, the majority of the participants upheld Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of the English language and the point of reference in learning English. Major reasons for this stance were found residing in the conventional anthropological episteme about the inseparability of language and culture (Brown, 1994), the ideology of the nation-language-culture trinity (Anderson, 2006), and the belief that a good knowledge of Inner Circle culture is facilitative for learning English. No significant difference was found between the students and the teachers.

In terms of the predominant support of Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of the English language, it seems that they did not realize the globalization of the English language. Currently, English has developed into an international language or a worldwide lingua franca (Jenkins, 2007, 2015; McKay, 2012) and “can be used by anyone as a means to express any culture heritage and any value system” (Smith, 1987, as cited in Alptekin, 1993, p. 140). At the same time, most communications in English are conducted between or among nonnative English speakers (NNSs) with different cultural identities, and in contexts or settings that bear no relevance to Inner Circle Culture (Cogo, 2012; McKay & Bokhorst-Heng, 2008). It follows that to uphold Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English and as the point of reference in learning and teaching English contradicts this sociolinguistic reality.

The endorsement for Inner Circle culture as the learning/teaching reference and target, whether explicitly or implicitly, can be attributed to the legitimacy that has been granted to Inner Circle scholarship in ELT convention. Traditionally, ELT theories are dominated by the anthropological episteme on the inseparability of language and culture (Brown, 1994, 2007) as well as expert discourses, such as Communicative Competence(Hymes, 1972), Acculturation Model (Schumann, 1986) and Integrative Motivation (Gardner & Lambert, 1972). Underneath these theoretical purports, however, lurks a native speakerist ideology, which upholds Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English and the reference model of ELT. Due to the historical-present academic hegemony of Inner Circle countries, all of these theories have been adopted indiscriminately as an authoritative guide or a legitimate yardstick for ELT research and practice in China. According to Gong (2011, as cited in Gong & Holliday, 2013), 95% of the ELT research articles published in China from 2005 to 2010 take the cultivation of students competence in intercultural communication simply as introducing to them Inner Circle culture; and most EFL textbooks are edited in accordance with Anglo-American culture. All of these discourses and practices inevitably have led to the constant reproduction of the pro-nativeness ideology, making the conformity to Inner Circle culture in ELT natural, normal and commonsensical. This may help explain why the majority of the participants in this study regarded Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English and the reference point in ELT.

Conclusion

All of the major findings presented in this article suggest the prevalence of a strong pro-nativeness ideology in relation to cultural orientations of ELT among the two participant groups, who, as an entirety, seemed to subjugate themselves to the nativespeakerist specter. However, an unneglectable percent of the students and teachers selected the “Not sure” answer to the Likert scale statements in praise of Inner Circle culture as the bedrock of English and the reference model in ELT. Arguably, this finding represents the ambivalence of those students and teachers produced by the conflicts between the traditional native speakerist discourse in support of Inner Circle culture and the discourse on the glocalization of English and cultural politics in ELT. That those students and teachers were lack of the knowledge on this issue may also lead to the central choice tendency (Chan, 2017). All these findings suggest that there is still a long way to go before the awake of ELT stakeholders on the cultural politics in ELT.

References

Alptekin, C. (1993). Target-language culture in EFL materials. ELT Journal, 47(2), 136-143.

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Refelctions on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised ed.). London: Verso.

Baker, W. (2011). From cultural awareness to intercultural awareness: culture in ELT. ELT Journal, 66(1), 62-70.

Brown, H. D. (1994). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford university press.

Chan, J. Y. H. (2017). Stakeholders perceptions of language variation, English language teaching and language use: The case of Hong Kong. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 38(1), 2-18.

Cogo, A. (2012). English as a lingua franca: Concepts, use, and implications. ELT Journal, 66(1), 97-105.

Dewey, M. (2015). Time to wake up some dogs! Shifing the culture of language in ELT. In Y. Bayyurt & S. Akcan (Eds.), Current perspectives on pedagogy for English as a lingua Franca (pp. 121-134). Berlin: De GruyterMounton.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972).Attitudes and motivation in second-language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Gong, Y., & Holliday, A. (2013). Cultures of change: Appropriate cultural content in Chinese school textbooks. In K. Hyland & L. L. C. Wong (Eds.), Innovation and change in English language education (pp. 44-57). New York: Routledge.

Hymes, D. (1972). On communicative competence.In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269-293). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Jenkins, J. (2007). English as a lingua Franca: Attitude and identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua Franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), 49-85.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2012). Individual identity, cultural globalization, and teaching English as an international language. In L. Alsagoff, S. L. Mackay, G. Hu, & W. A. Renandya (Eds.), Principles and practices for teaching English as an international language (pp. 9-27). New York: Routledge.

Liu, J., & Li, S. (2019). Native-speakerism in English language teaching: The current situation in China. Newcastle upon Tynne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

McKay, S. L. (2012). Teaching materials for English as an international language. In A. Matsuda (Ed.), Principles and practices of teaching English as an international language (pp. 70-83). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

McKay, S. L., & Bokhorst-Heng, W. D. (2008). International English in its sociolinguistic contexts: Towards a socially sensitive EIL pedagogy. New York: Routledge.

Rose, H., & Galloway, N. (2019).Global Englishes for language teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Savignon, S. J., & Wang, C. (2003). Communicative language teaching in EFL contexts: Learner attitudes and perceptions. IRAL, 41(3), 223-250.

Schumann, J. H. (1986). Research on the acculturation model for second language acquisition. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 7(5), 379-392.

vanDijk, T. A. (2008). Discourse and power. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

vanLeeuwen, T., &Wodak, R. (1999). Legitimizing immigration control: A discourse-historical analysis. Discourse studies, 1(1), 83-118.

杂志排行

Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- The Beatific Vision as Described by Blaise Pascal,Friedrich Nietzsche and Carl Jung

- Research on the Reading Comprehension and Aesthetic Experience of Poster Design Based on Gadamer’s Philosophy

- Children’s Picture Book is a Powerful Method of Cultural Communication of Zhuang Folk Tales

- Feasibility Investigation and Development Exploration on Popularizing the Method of English Fragmented Mobile Learning of Undergraduates

- The Establishment of Female Authority of Voice in The Company of Wolves

- A Study of Verbal Humor in Public Speech from the Perspective of Relevance Theory and Cooperative Principle—Taking TED Talks as An Example