Associations between serum uric acid and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer: A cohort study

2021-01-13ChongFeiHuangJunJunHuangNingNingMiYanYanLinQiangShengHeYaWenLuPingYueBingBaiJinDuoZhangChaoZhangTengCaiWenKangFuLongGaoXunLiJinQiuYuanWenBoMeng

Chong-Fei Huang, Jun-Jun Huang, Ning-Ning Mi, Yan-Yan Lin, Qiang-Sheng He, Ya-Wen Lu, Ping Yue, Bing Bai, Jin-Duo Zhang, Chao Zhang, Teng Cai, Wen-Kang Fu, Long Gao, Xun Li, Jin-Qiu Yuan, Wen-Bo Meng

Abstract

Key Words: Uric acid; Liver neoplasms; Pancreatic neoplasms; Gallbladder neoplasms; Biliary tract neoplasms; Cohort studies

INTRODUCTION

Hepatobiliary-pancreatic (HBP) cancer includes liver cancer, biliary tract cancer, gallbladder cancer and pancreatic cancer[1-3]. The number of new cases of HBP cancer worldwide in 2018 was approximately 1.85 million, accounting for 10% of all newly diagnosed cancer cases and resulting in a great financial burden[4,5]. Due to the large number of HBP cancer cases, from the perspective of prevention[6,7], identifying highrisk populations has become an urgent public health issue[8-10].

Serum uric acid (SUA) is the final product of purine nucleotides that are ingested or endogenously synthesized and mainly metabolized by the liver[11]. Because of its function of inhibiting reactive oxygen species formation, SUA was considered a protective factor against cancer[12], and studies have indicated that elevated SUA was associated with low cancer mortality[13,14]. However, subsequent experiments revealed that SUA was associated with inflammatory mediators, which act as cancer-promoting factors[15,16]. A meta-analysis conducted in 2019 that included eight cohort studies investigating cancer incidence, and SUA suggested that high SUA levels increased the risk of all cancers[17].

However, few previously published studies have focused on the SUA levels and the incidence of cancer at specific sites, and none of these studies highlighted HBP cancer. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate the associations between SUA and the HBP cancer risk based on the UK Biobank cohort.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and population

The UK Biobank is a national and international health resource with over 500000 participants aged 40-69 years recruited from all over the United Kingdom from 2006-2010. More details of the UK Biobank are available elsewhere[18]. The UK Biobank has received ethical approval from the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee, the England and Wales Patient Information Advisory Group and the Scottish Community Health Index Advisory Group. All participants provided written informed consent. In this analysis, we excluded 26868 participants with any cancer prior to recruitment (except for non-melanoma skin cancer 10threvision of the International Classification of Diseases C44) and 31197 participants with missing SUA data (Figure 1). Eventually, 444462 participants were included in the final analysis and were grouped by quartiles of SUA (Q1-Q4).

Data collection

The baseline characteristics were collected by self-completed touch-screen questionnaires, computer-assisted interviews and physical measurements. The data retrieved for the analysis included age, gender, education, ethnic group, family history of cancer, annual household income and lifestyle habits such as fruit and vegetable intake (more than five portions or not), alcohol consumption, smoking status, physical activity (categorized according to the standard International Physical Activity Questionnaire guidelines[19]as high, moderate or low) and body mass index [body mass index (BMI), calculated as weight divided by height squared, kg/m2). Approximately 45 mL of blood and 9 mL of urine were collected to measure specific biomarkers by using the latest analytical methods in a dedicated facility in Stockport. The samples were stored separately for the subsequent detection and stored at -80 °C and -180 °C[20]. SUA was measured by a Beckman Coulter AU5800 (BC, United States) using enzymatic determination (Uricase PAP).

Diagnosis of cancer cases

Information regarding the cancer diagnoses in the UK Biobank is provided by the National Health Service (NHS) Digital and Public Health England for participants residing in England and Wales and the NHS Central Register for participants residing in Scotland. The general classification of the cancer cases was based on the 10threvision of the International Classification of Diseases codes. The primary outcomes in this study were liver cancer (C22), gallbladder cancer (C23), biliary tract cancer (C24) and pancreatic cancer (C25).

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics are presented as numbers (percentages) for the categorical variables and means (standard deviations) for the continuous variables. Cox regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the association between SUA and HBP cancer. The potential confounders were adjusted gradually in three models. In model 1, we adjusted for the general demographic characteristics (gender, age, education, ethnic group and family history of cancer). Then, we further adjusted for lifestyle factors (alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, physical activity, fruit and vegetable intake) in model 2. Because obesity is closely related to the SUA levels and cancer risk, in model 3, we adjusted for BMI separately in addition to the variables included in model 2. The potential nonlinear associations between the SUA levels and the HBP cancer risk were investigated by fitting restricted cubic splines in a fully adjusted Cox regression model. In addition, considering the large gender difference in the distribution of SUA, we also conducted a gender-stratified analysis.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to verify the stability of our results by excluding participants with less than 2 yrs of follow-up from the fully adjusted Cox regression models. All statistical analyses were conducted by using R software (version 3.5.0, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

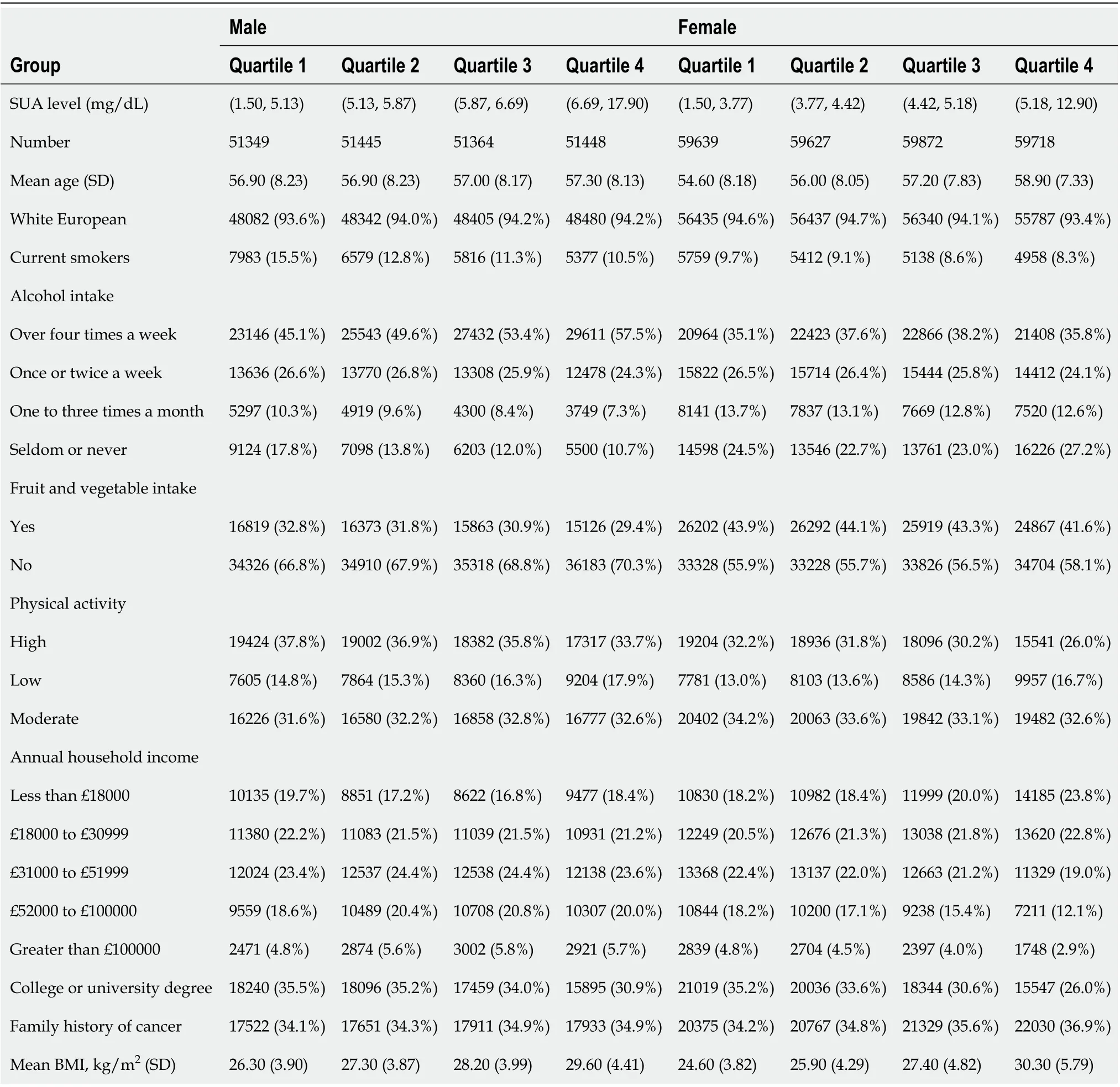

This study included 444462 participants (Tables 1 and 2). There were fewer males in the quartiles with higher SUA levels and fewer females in the quartiles with lower SUA levels. As the SUA level quartiles increased, the participants tended to be older, have a higher BMI, consume more alcohol, consume less fruit and vegetables and have fewer college or university degrees.

我像疯了一样跑到医院,妈的手脚已经被绑在床上了,身上插满了管子,脖子上还挖了一个洞。大夫说怕妈乱抓管子,就把她绑起来了。

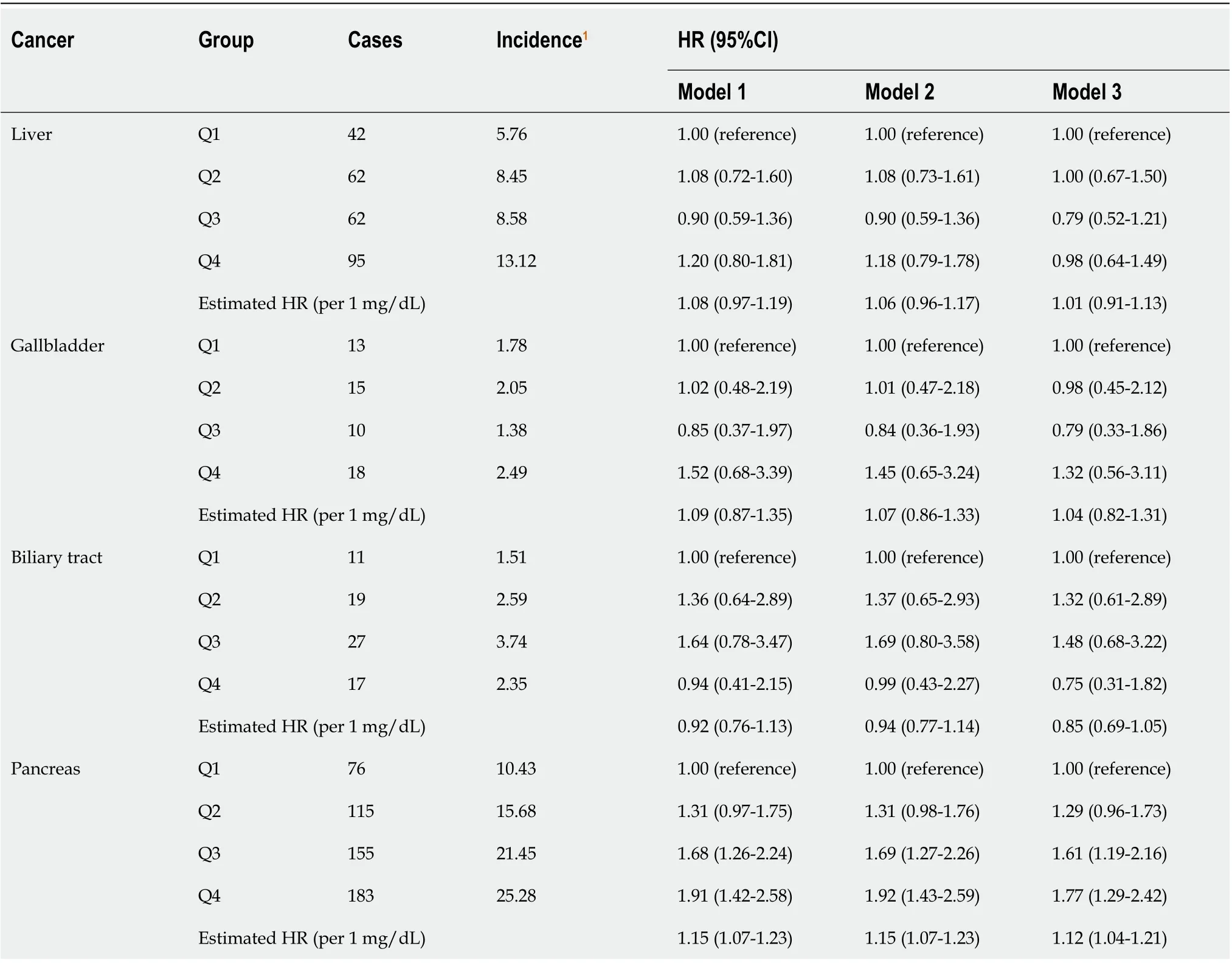

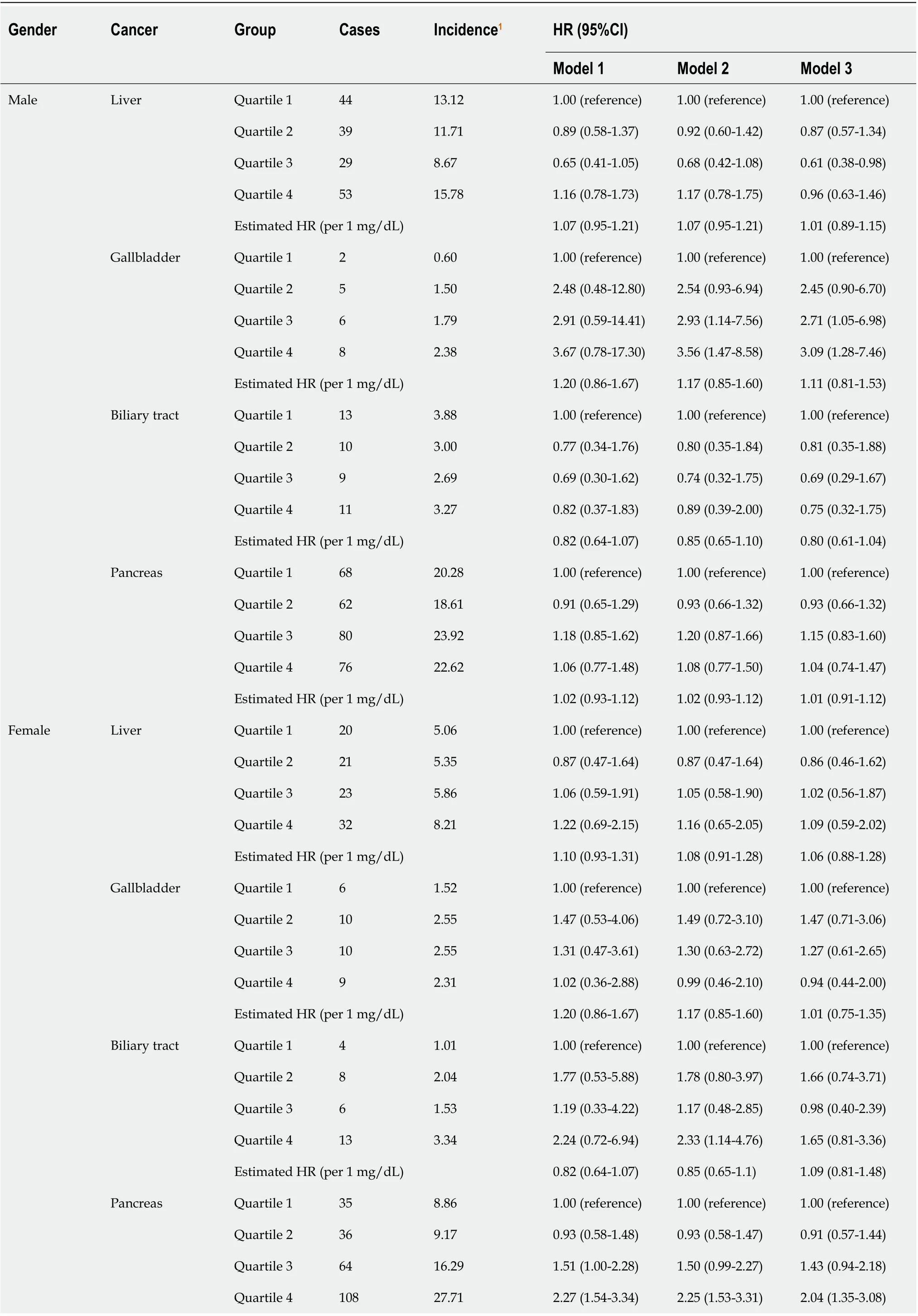

In total, 920 participants developed HBP cancer during a median of 6.6 yrs of follow-up. The risk of pancreatic cancer tended to increase with the SUA levels (adjusted HR per 1 mg/dL increase in SUA = 1.12, 95%CI: 1.04-1.21). In model 1, the HR of the pancreatic cancer risk was 1.91 (95%CI: 1.42-2.58) in the highest quartile (Q4) of SUA compared with the lowest quartile (Q1). After adjusting for potential confounders, the HR was gradually attenuated, but the association still existed in model 3. The risk of pancreatic cancer in the highest quartile of SUA increased by 77% compared with that in the lowest quartile (HR 1.77, 95%CI: 1.29-2.42, Table 3).

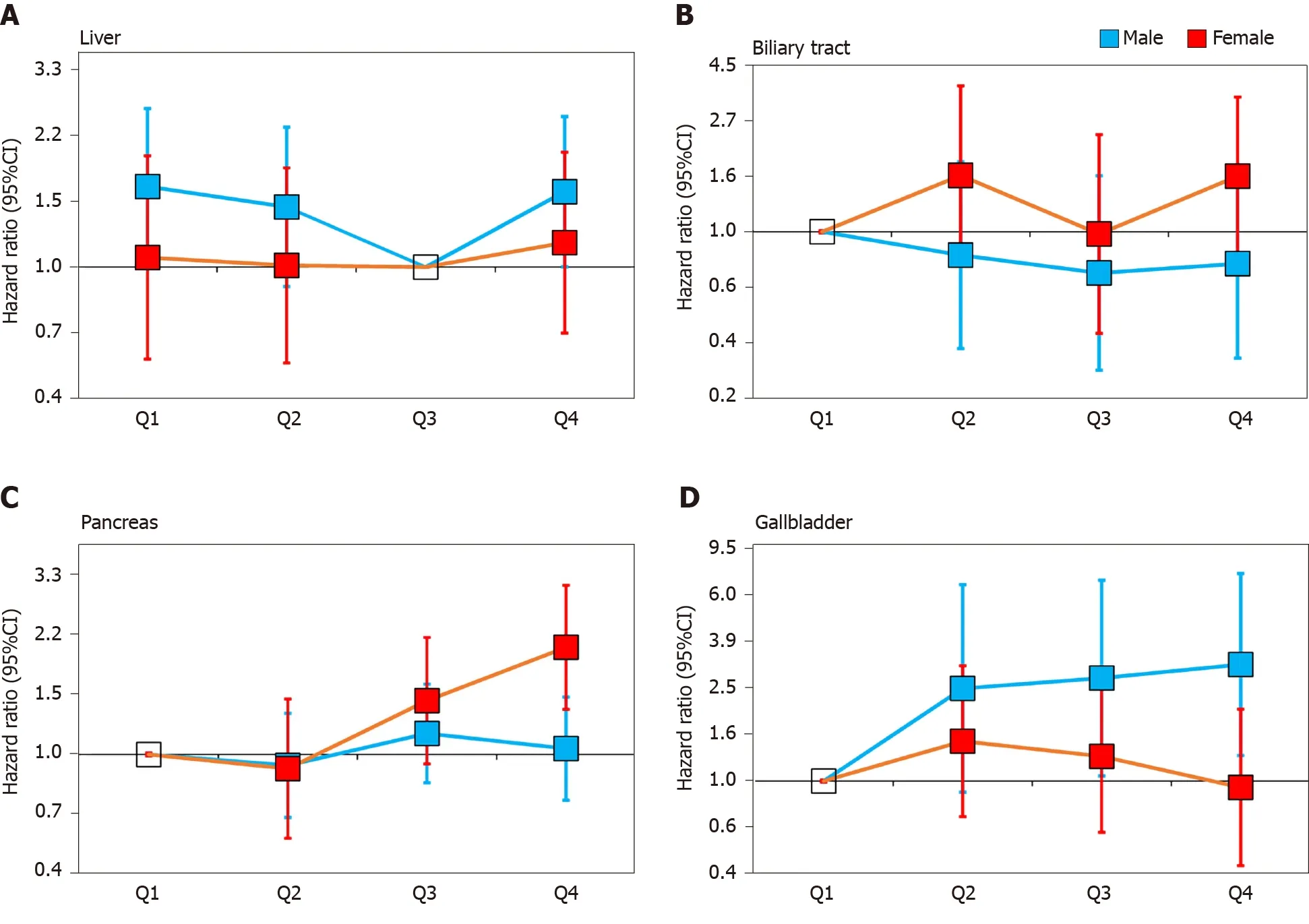

The stratified analysis results showed that SUA had different effects on HBP cancer between the males and females. In the male population, after fully adjusting for potential confounders, the risk of liver cancer decreased in the second quartile (HR 0.87, 95%CI: 0.57-1.34) and the third quartile (HR 0.61, 95%CI: 0.38-0.98) compared with that in the lowest quartile. However, in the highest quartile (HR 0.96, 95%CI: 0.63-1.46), the HR of liver cancer was increased compared with that in the third quartile (Figure 2A). In contrast to liver cancer, the risk of gallbladder cancer in the second quartile (HR 2.45, 95%CI: 0.90-6.70), the third quartile (HR 2.71, 95%CI: 1.05-6.98) and the highest quartile (HR 3.09, 95%CI: 1.28-7.46) were all higher than that in the lowest quartile (Figure 2D). The risk of biliary tract cancer and pancreatic cancer did not differ between the lowest and other quartiles (Figure 2B).

In the female population, no difference was found between the lowest quartile and the other quartiles of the SUA levels in gallbladder cancer and liver cancer. Regarding the biliary tract cancer risk, the HR of the highest quartile of SUA was 2.33 (95%CI:1.14-4.76) compared with the lowest quartile in model 2 (Table 4). However, after additionally adjusting for BMI in model 3, the risk was attenuated (HR 1.65, 95%CI: 0.81-3.36). Regarding the pancreatic cancer risk, the risk increased by 1.33 times per 1 mg/dL SUA level in model 3 (HR 1.33, 95%CI: 1.21-1.47, Table 4). After an additional adjustment for potential confounders, the highest quartile still showed an increased risk compared with the lowest quartile (HR 2.04, 95%CI: 1.35-3.08, Figure 2C).

Table 1 Baseline characteristic

Figure 3 shows the evaluation of the potential nonlinear relationship with HBP cancer. A strong linear dose-response relationship was observed between the SUA levels and the risk of pancreatic cancer (P-nonlinear > 0.05,P-overall < 0.0001, Figure 3). After the stratification by genders, the SUA levels exhibited a linear doseresponse relationship with the risk of pancreatic cancer in both the male and female populations, but the effect was much stronger in the females than in the males (Pinteraction < 0.0001, Figure 4). The liver cancer risk showed a U-shaped relationship with the SUA levels (P-nonlinear < 0.05,P-overall < 0.0001, Figure 3); however, a nonlinear relationship with the risk of liver cancer was observed only in the males (P-nonlinear < 0.05, Figure 5). Additionally, regarding the SUA levels and the risk of gallbladder cancer and biliary tract cancer, a linear dose-response relationship was observed.

Table 2 Baseline characteristic stratified by gender

These results suggest that high SUA levels are associated with an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in females and gallbladder cancer in the males. Moreover, the risk of liver cancer showed a U-shaped association in the males as both too high and too low levels of SUA were associated with an increased risk. We did not observe sufficient evidence of an association between the SUA levels and biliary tract cancer.

In the sensitivity analysis, by excluding cases that were documented in the first 2 yrs, we did not observe major changes in the primary results (Tables 5 and 6).

DISCUSSION

As a very common metabolite, SUA has multiple effects on the human body, and high SUA levels have been considered harmful. Previous studies have found that elevated SUA levels are associated with gout, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia,obesity[21-25]and cancer[26-28]. Kolonelet al[29]conducted a prospective cohort study including 7889 males and indicated that high SUA levels were associated with a high prostate cancer risk. Denget al[30]included 8274 patients with type 2 diabetes from the Shanghai Diabetes Registry and found that in female diabetic patients, SUA was positively associated with the cancer risk. Another Mendelian randomization study analyzed 86210 individuals from the Copenhagen General Population Study and indicated that high SUA levels were associated with an increased cancer risk[31]. In our research, we also found a relationship between high SUA levels and an increased risk of pancreatic cancer in females and gallbladder cancer in males.

Table 3 Effect of serum uric acid on hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer

SUA has been found to be associated with inflammatory stress, which is closely related to the occurrence of cancer. Components of the inflammatory microenvironment, such as adiponectin, C-reactive protein, leptin and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), which are closely related to SUA, were found to be associated with cancer development[15,32]. In addition, in our study, the SUA levels were positively correlated with pancreatic cancer and gallbladder cancer, and COX-2 was widely expressed in tumor tissues[33,34]. Xieet al[35]conducted anin vitroexperiment examining the effect of COX-2 on the angiogenesis of pancreatic cancer cells and indicated that COX-2 was positively associated with the microvascular density, promoting pancreatic cancer cell growth. Celecoxib, a selective COX-2 inhibitor, was found to enhance the effect of chemotherapeutic drugs on pancreatic cancer and inhibit the proliferation of gallbladder cancer cells[36,37]. Ohtsuboet al[38]confirmed that SUA regulates the expression of COX-2 through XOR inin vivoandin vitroexperiments, which may explain the association between SUA and cancer. Based on the evidence from previousepidemiological and experimental studies along with our findings, high SUA levels are likely to lead to an increased risk of cancer in various sites, suggesting that we should pay attention to reducing the SUA levels to reduce the risk of cancer.

Table 4 Effect of uric acid on hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer stratified by gender

Estimated HR (per 1 mg/dL)1.02 (0.93-1.12)1.02 (0.93-1.12)1.33 (1.21-1.47)Model 1 adjusted for age, education, ethnic group and family history of cancer. Model 2 adjusted for age, education, ethnic group, family history of cancer, alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity. Model 3 additionally adjusted for body mass index based on model 2.1Per 100000 person years. HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Table 5 Sensitivity analysis

Although many studies have shown that high SUA levels are a risk factor for cancer, some evidence suggests that the SUA levels should not be too low. Ameset al[12]. first proposed the hypothesis that SUA might act as a protective factor against cancer due to its antioxidant function and its function as a scavenger of singlet oxygen and free radicals. Some epidemiological studies also supported this hypothesis. Tilmanet al[39]conducted a population-based study of endogenous antioxidants, including albumin, bilirubin and SUA, and indicated that a high SUA level was associated with a low risk of breast cancer and low mortality of all cancers. Patients with oral cancer and lung cancer also had lower SUA levels[40,41]. The results of a cohort study confirmed that low SUA levels were associated with lung cancer[42]. In our study, we found that as the SUA levels increased, the risk of liver cancer first exhibited a downward trend. Male participants in the third quartile had a 39% decreased risk of liver cancer (HR 0.61, 95%CI: 0.38-0.98) compared with those in the lowest quartile, possibly due to the protective function of SUA. However, as the SUA levels further increased, the risk of liver cancer also increased. In the highest quartile, the risk of liver cancer was notably higher than the risk in the third quartile, revealing a U-shaped relationship. Strasaket al[43]conducted a population-based study involving Austrian men and suggested a Jshaped effect of SUA on the risk of overall cancer incidence, which is similar to our results in liver cancer, indicating that SUA within a proper range is better in thecontext of liver cancer, and too low or too high levels of SUA represent a risk factor for liver cancer. Similarly, COX-2 is overexpressed during the development of liver cancer and tumor tissues, while normal liver tissues scarcely express COX-2[44,45]. Chenet al[46]showed that COX-2 was a leading factor related to liver cancer in a spontaneous liver cancer mouse model that overexpressed COX-2 specifically in the liver. As the SUA levels increase, the cancer-promoting effect of COX-2 overexpression may be stronger, leading to the U-shaped association between SUA and liver cancer.

Table 6 Sensitivity analysis stratified by gender

Figure 2 Associations between uric acid and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer stratified by gender. Adjusted for age, education, ethnic, family history of cancer, alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity and body mass index. A: Liver; B: Biliary tract; C: Pancreas; D: Gallbladder. CI: Confidence interval.

In the gender stratified analysis, we found that only gallbladder cancer and liver cancer were associated with SUA in males, and that pancreatic cancer was related to SUA in females. This finding might be related to the reduced number of cases after the stratification as the statistical power was insufficient. In addition, we found that the risk associated with SUA in biliary tract, gallbladder and liver cancer in the female participants was generally higher than that in the male participants. Similar results were found in previous studies. A Chinese cohort study found that high SUA levels were associated with cancer risk in diabetic female patients[30]. Yanet al[47]conducted a systematic review and suggested that high SUA levels were associated with a high cancer risk, especially among females. Further analysis suggested that SUA and gender had an interactive effect on pancreatic cancer because sex hormones may lead to different sensitivity to SUA. More research is still required to reveal such gender differences.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to focus on the association between SUA and HBP cancer. The main strength of our research is the large sample size. We included over 0.44 million participants in this analysis, allowing us to discover the relationship between the SUA levels and HBP cancer at multiple levels. Additionally, the UK Biobank comprehensively collected data related to established HBP cancer risk factors, allowing us to sufficiently control for potential confounders. We also investigated the potential nonlinear relationship, which provided insight into the carcinogenicity of SUA and contributes to individualized cancer prevention.

This study has limitations. First, as an observational study, we cannot confirm the causal-relationship between SUA and HBP cancer. Second, due to the limited number of cases, we were unable to conduct further stratified analyses of some variables. Third, in the UK Biobank, most included people were white Europeans, and the role of SUA in other races is unclear. More research is needed to compensate for the above limitations.

Figure 3 Dose response of uric acid and hepatobiliary-pancreatic cancer risk. Adjusted for genders, age, education, ethnic, family history of cancer, alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity and body mass index. The reference uric acid level for these plots (with hazard ratio fixed as 1.0) was 4.0 mg/dL. CI: Confidence interval.

Figure 4 Association between uric acid level and pancreatic cancer with effect modification by gender. Adjusted for age, education, ethnic, family history of cancer, alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity and body mass index. The reference uric acid level for these plots (with hazard ratio fixed as 1.0) was 4.0 mg/dL.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, SUA is likely to have gender-specific effects on HBP cancer. High SUA levels represent a risk factor for gallbladder cancer in males and have a strong effect on pancreatic cancer in females. SUA levels that are too high or too low are associated with an increased risk of liver cancer in males. In clinical and public health practice, the management of either too high or too low SUA levels may contribute to the prevention of HBP cancer. Future research is required to confirm our conclusion and investigate the mechanisms underlying these associations.

Figure 5 The effect of uric acid on hepatobiliary cancer stratified by gender. Adjusted for age, education, ethnic, family history of cancer, alcohol intake, smoking status, annual household income, fruit and vegetable intake and physical activity and body mass index. The reference uric acid level for these plots (with hazard ratio fixed as 1.0) was 4.0 mg/dL.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

猜你喜欢

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Prognostic value of changes in serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels for preoperative chemoradiotherapy response in locally advanced rectal cancer

- Development and validation of a three-long noncoding RNA signature for predicting prognosis of patients with gastric cancer

- Use of the alkaline phosphatase to prealbumin ratio as an independent predictive factor for the prognosis of gastric cancer

- Active tuberculosis in inflammatory bowel disease patients under treatment from an endemic area in Latin America

- Prevalence and predictors of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in South Asian women with polycystic ovary syndrome

- COVID-19 in a liver transplant recipient: Could iatrogenic immunosuppression have prevented severe pneumonia? A case report