Primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the right posterior tongue

2020-12-17YuZhouHangChengZhouHuiPengZhiHongZhang

Yu Zhou, Hang-Cheng Zhou, Hui Peng, Zhi-Hong Zhang

Yu Zhou, Hui Peng, Zhi-Hong Zhang, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230001, Anhui Province, China

Hang-Cheng Zhou, Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230001, Anhui Province, China

Abstract

Key Words: Small cell carcinoma; Neuroendocrine carcinoma; Oral cavity; Head and neck; Extrapulmonary

INTRODUCTION

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (SNEC) is the most common type of pulmonary neoplasm and is an aggressive malignant tumor with a high tendency for regional and distant metastasis. Extra-pulmonary SNECs account for 2.5%-5% of all SNECs, of which head and neck SNECs account for 10%-15%[1]. The first case of SNEC in the head and neck was reported in 1963, and the larynx is the most common site, followed by the salivary glands and the sinonasal region[2]. Primary SNEC in the oral cavity is extremely rare and to date only 11 primary SNECs occurring in the oral cavity have been reported in the English literature[3-13].

The management of extra-pulmonary SNECs has not been standardized, but is extrapolated from pulmonary SNEC due to their similar clinicopathologic features[14,15]. In addition to chemotherapy as an effective therapeutic modality, radical surgery and radiation therapy may also play an important role depending on the primary site and clinical stage of the tumor[16]. The current report presents a rare case of primary SNEC arising in the right posterior tongue. The clinicopathologic characteristics of this rare tumor are discussed and the relevant literature is reviewed.

NEW CASE OF SCNC

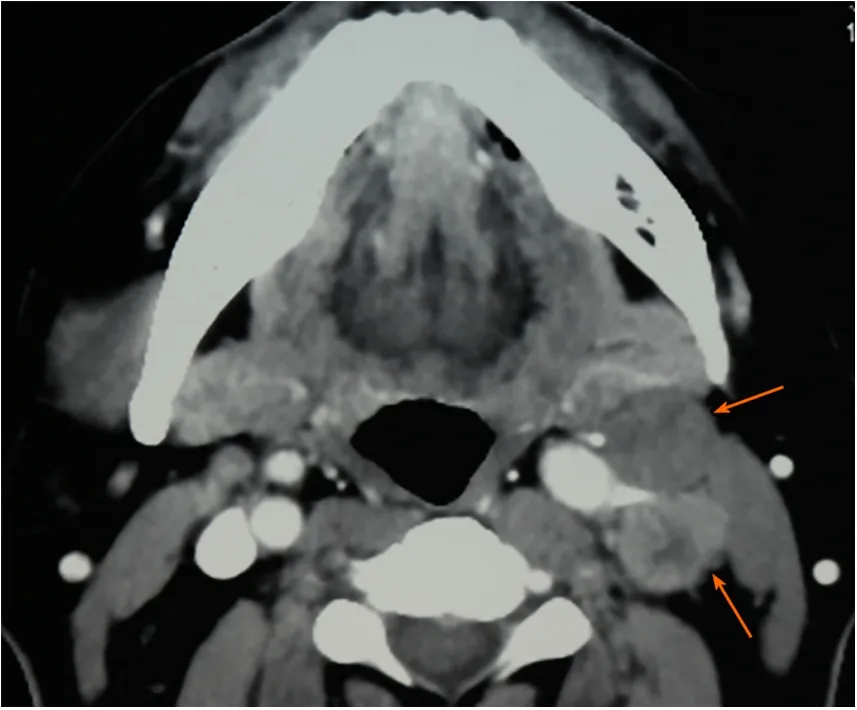

A 46-year-old man, who had a 30-year history of smoking and alcohol consumption, presented to the oral and maxillofacial department in September 2013 with a painful mass which grew rapidly of the right posterior tongue during the previous 3 mo and a painful mass in the contralateral upper jugular area for 1 mo. Physical examination identified a hard polypoid mass of the right posterior tongue, measuring 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm, with obvious tenderness and low mobility (Figure 1). A painful mass with low mobility, measuring 2.0 cm × 3.0 cm, in the contralateral upper jugular area was also identified.

Computerized tomography (CT) scanning showed an ill-defined mass with heterogeneous enhancement in the right posterior tongue and contralateral cervical lymph node enlargement (Figure 2). A CT scan of the chest and abdomen and a positron emission tomography-CT scan revealed no abnormalities. Findings from laboratory examinations, including routine blood, blood biochemistry and urine analysis, were within normal limits. An incision biopsy under local anesthesia was performed. Microscopically, round and spindly small cells presented with ovoid or spindle shaped nuclei, fine granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm, forming broad nests, sheets or cord shapes (Figure 3). Immunohistochemically, these cells were positive for synaptophysin (referred to as syn), N-CAM (CD56), chromogranin A and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 (Figure 4). The proliferation index evaluated by Ki-67 labeling was 90% (Figure 5). The cells were negative for human melanoma black45 (referred to as HMB-45), cytokeratin 20 (referred to as CK20), vimentin, S100 protein, leucocyte common antigen, CD99, smooth muscle actin and thyroid transcription factor1.

A combined modality therapy was approved by multidisciplinary discussion. After two cycles of chemotherapy (cisplatin 75 mg/m2, day 1 and etoposide 100 mg/m2, day 1-3, 3 wk per cycle), the primary tumor and cervical lymph nodes partially decreased according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors. Radical resection, including extensive resection of the primary tumor with contralateral radical and homolateral functional neck dissection and reconstruction of the tongue with a left free forearm flap was performed. The diagnosis of SCNC was confirmed by postoperative pathology. A 60 Gy dose of radiotherapy was administered after surgery. The patient remained tumor-free for 20 mo before his death due to gastrointestinal metastasis.

Figure 1 Clinical photograph showing the gross appearance of tumor in the right root of tongue.

Figure 2 Preoperative computerized tomography scan showing contralateral cervical lymph nodes enlargement (orange arrows).

DISCUSSION

According to the World Health Organization Blue Book 2017, neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) are now classified into three categories: Well-differentiated, moderately-differentiated and poorly-differentiated, which is additionally divided into two subtypes: SNEC and large cell NEC[17]. Primary NECs in the oral cavity have been subclassified into typical carcinoid, atypical carcinoid, large cell NEC and SNEC[18]. The synonyms for SNEC include “small cell carcinoma”, “oat cell carcinoma” and “anaplastic small cell carcinoma”[19]. Primary SNEC occurring in the oral cavity is extremely rare and has a poor prognosis. Positron emission tomography-CT and CT images confirmed that the current patient had a rare primary SNEC of the oral cavity, and not a metastatic SNEC arising from the lung.

Figure 4 Immunohistochemical analysis showed positivity for (A) synaptophysin, (B) chromogranin A, and (C) cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Magnification: × 200.

Figure 5 About 90% of the tumor cells showed Ki67+ nuclear staining, suggesting a high proliferation activity.

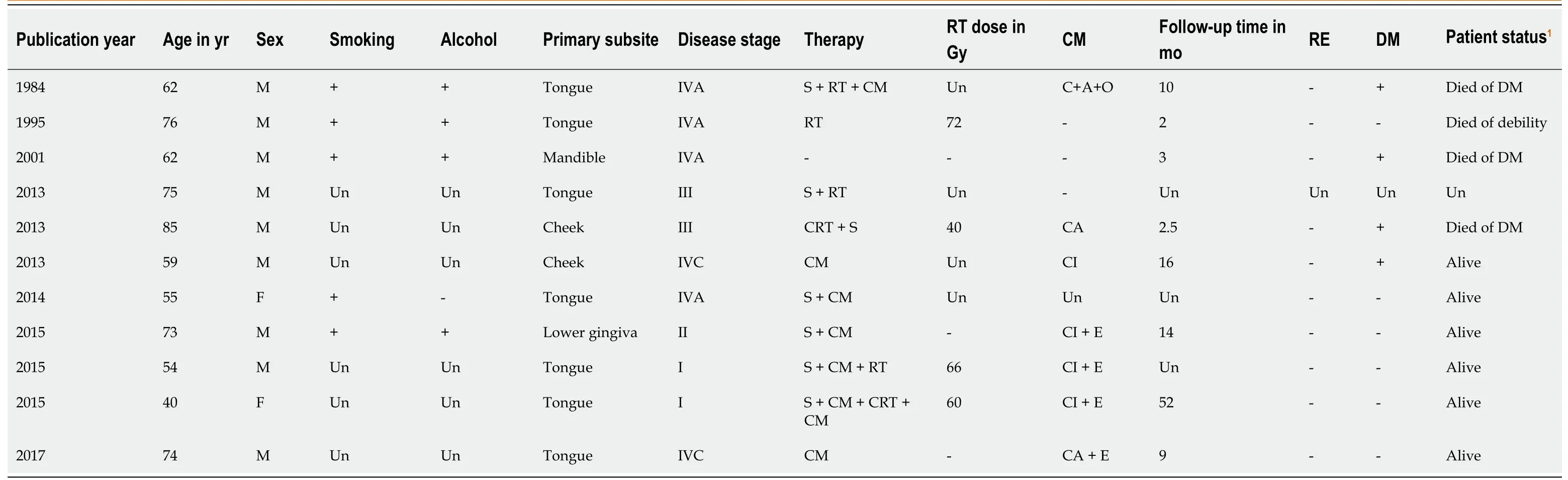

The clinical characteristics of these rare cases reported in the English literature are shown in Table 1. Most of the patients were men (81.8%). The median age of the patients was 67.5 years (range: 40-83 years). Smoking and alcohol abuse, as the major risk factors, were also common among these patients. These results are similar to those of NEC in the head and neck[10]. The tongue was the most common subsite (63.6%). Minor salivary glands may be the prevailing origin of primary SNEC in the oral cavity[11]. Most of the patients had lymph node and distant metastasis with stage III, IVA, IVB and IVC tumors (72.7%), which are also similar to the results of previous studies on extra-pulmonary SNEC in the head and neck. In patients with positive cervical lymph nodes, the recurrence rate is high and distant metastasis frequently occurs. In addition, these patients have a poor median survival of 10.0 mo and a 2-year survival rate of 15.7%[16]. Therefore, a comprehensive examination is mandatory to exclude distant metastasis. The outcomes of the previously reported 11 patients were as follows: 3 died of tumor, 1 died from other causes, 6 showed no evidence of disease, and the status of 1 patient was unknown.

The definite diagnosis of SNEC depends on histopathology and immunohistochemistry analyses. Morphological examination showed extensive proliferation of round and spindly small cells with ovoid-to-spindle shaped nuclei, fine granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli and scant cytoplasm, which could help in the differential diagnosis of typical and atypical carcinoids and large cell NEC[8]. These small cells formed broad nests, sheets or cord shapes. Necrosis is typically extensive and the mitotic count is high. The presence of electron-dense and neurosecretory granules is distinctive in SNEC[20]. The cells are distinctively positive for neuroendocrine markers including syn, N-CAM (CD56) and chromogranin A[17]. High Ki-67 labeling (90%) indicates high proliferative activity of tumor cells[8].

Immunohistochemical staining is crucial for the differential diagnosis of SNEC from other malignancies. Extensive mitotic index and necrosis can distinguish SNEC from typical and atypical carcinoids. In contrast to SNEC, large cell NEC contains cells witha relatively large cytoplasm and vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Primary cutaneous high-grade NEC, which mainly develops due to ultraviolet light exposure, is termed Merkel cell carcinoma. Primary mucosal high-grade NEC, which typically develops because of heavy smoking and alcohol abuse, is called SNEC. In addition, CK20 is commonly positive in Merkel cell carcinoma, and is negative in SNEC[21]. HMB45 and S100 are special markers for malignant melanoma and malignant lymphoma. They can be used for detecting metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung when thyroid transcription factor1 is positive[11]. Cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and P63 staining is helpful in identifying a basal cell carcinoma or a squamous cell-originated tumor[6,10,11].

Table 1 Clinical characteristics of the primary small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas in the oral cavity

Due to the paucity of primary SNECs in the oral cavity, the lack of definitive treatment recommendations is a challenge for clinicians. The appropriate treatment strategies for extra-pulmonary SNECs are extrapolated from their pulmonary counterparts[14]. A variety of therapeutic modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and chemoradiotherapy, are thought to be appropriate treatments[16,22]. Surgery could be curative when SNECs are limited within the primary sites. In addition, surgery is the main treatment of NECs at different body sites and has been reported to significantly improve overall survival, over other single-modality treatments. To decrease local recurrence of SNECs, a wide excision is mandatory (up to 3 cm)[7]. In our case, the patient underwent extensive surgical excision of the primary tumor.

As SNEC is an extremely aggressive malignancy with high rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis, multimodal therapy is required. For patients without distant metastasis, chemotherapy can reduce tumor size and decrease the risk of distant metastasis. In early and locally advanced SNECs of the head and neck, chemoradiotherapy is also an effective treatment[16]. In patients with extensive SNEC, chemotherapy is recommended to prolong survival and improve prognosis[6,12]. The combination of cisplatin and etoposide is the first-line chemotherapy regimen for SNEC[23]. In recent research, chemotherapy in combination with first-line atezolizumab prolonged survival rate compared with chemotherapy alone in the treatment of extrapulmonary SNECs with distant metastases[2].

Furthermore, a few novel therapeutic strategies for small cell carcinoma of the lung which are unsuccessful, including mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, breakpoint cluster region–Abelson tyrosine kinase inhibitors, epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, deoxyribonucleic acid repair inhibitors, immunotherapies, and anti-delta-like protein 3 antibody-drug conjugates, have been introduced[24,25]. Of the 11 patients with primary SNEC in the oral cavity, 1 patient received radiotherapy only, due to his poor physical condition. Chemotherapy was the most common treatment in the majority of patients (75%). In the current case, the patient showed partial remission after two cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. However, the patient died when gastrointestinal metastasis occurred 20 mo after treatment.

CONCLUSION

Primary SNEC occurring in the oral cavity represents a rare clinical entity, and is aggressive with a poor prognosis. The diagnosis of SNEC requires morphology and immunohistochemistry analyses. Due to its highly metastatic characteristics, a comprehensive clinical examination of the neck, chest, abdomen and bone is mandatory in SNEC patients. Multimodal therapy may be an effective treatment strategy for SNEC of the oral cavity. However, more effective treatments to improve the survival rate of patients with SNEC in the oral cavity are required.