《20世纪中国戏剧史》英文版译后所思

2020-09-26张强

张强

《20世纪中国戏剧史》英文版的海外合作出版机构是泰勒-弗朗西斯出版集团,该集团有着强大的全球市场销售和推广能力,旗下学术分社罗德里奇(Routledge)在国际市场更是具有极高的知名度及学术影响力。

一

中国戏曲学院傅谨教授花了20年功夫完成的专著《20世纪中国戏剧史》于2016年6月由中国社会科学出版社出版,一经见面,在中国戏剧界引起强烈的反响。

这部皇皇120万字的巨著,将20世纪中国戏剧以1949年为节点分上、下两段阐述,从1900年庚子事变导致的戏剧艺术变革写到2000年先锋戏剧《切·格瓦拉》,重新描述整个20世纪中国戏剧历史的改变变迁与演进历程。其史料详实,论述缜密,文风平实流畅。

不同于一般从“观念史、作品史”角度研究戏剧,该书的视野更为宽阔,将中国戏剧置于现代化的发展进程中进行考察,从政治、艺术、娱乐三个不同层面,从传统与现代、本土与西化、政治与艺术、城市与民间、人本与生态、演出与市场等多重辩证关系,探讨中国现代戏剧艺术发展的基本特征与规律、成就与教训、传承与发展等重大问题。

作者以恢宏的视野,全面叙述了整个20世纪中国戏剧各种剧种,尤其是话剧的发展、变迁与演化的历史进程。这是一部有关20世纪中国戏剧的权威著作,对于研究中国现、当代戏剧发展的国内外专家学者、戏剧工作者以及戏剧爱好者来说,是一本不可多得的文献资料。

学界非常重视这部专著。《20世纪中国戏剧史》在2016年面世后,第二年就被立项为“国家社科基金”项目。由此可见此书在中国戏剧界的巨大影响力。

二

这可能是国内第一部较全面、系统地向国外读者介绍中国现当代戏剧发展的专门著作。由于书中有大量的让我感到陌生的中国传统文化知识、戏剧专门知识与专业术语,我在接到翻译任务后,内心诚惶诚恐、如履薄冰,生怕自己学识简陋,力所难逮,辜负原著作者傅谨教授与中国社会科学出版社的厚望。因此,在动笔翻译之前,我认真阅读原著,对于自己不懂的专业知识与术语先记下,大量翻阅工具书与相关文献资料,存疑的地方一个不放过,把疑惑点一一弄清、弄懂后才动笔翻译。事实上,我花在查找、翻阅、学习相关资料的时间要比翻译所花的时间要多,力求译文能忠实地反映原著的内容,同时让国外的研究者、戲剧工作者与普通读者能看懂这种中国传统文化元素较为丰富的艺术,以求使戏剧工作者能够更好、更有效地进行东西方文化的交流。

由于世界各个民族生活在不同的地域,在发展的长河中,孕育出各民族不同的思想与道德观念、政治制度、历史与文化传统、社会习俗、生活习惯等,因此,在国际交往与对外文化交流中,翻译是极其重要的一个环节。然而,让外国人士借助于译文了解中国的事物并非易事。即使同为盎格鲁撒克逊人后裔的英国人与美国人,其所使用的同一种语言,在某些词汇的内涵与语言习惯上也都存在着差异。比如英语单词homely的内涵,在英国英语(British English)中,这个词有“善良、淳朴的意思”,但在美国英语(American English)中,homely的意思是“蠢笨的、难看的”。该词的意思在大西洋两岸用同一种语言的“亲戚”中就有了别样的意义。

汉语与英语源于不同的地域和不同的政治、文化、生活环境,是两种完全不同的语言体系,词汇的形成与来源截然不同,致使语言的使用方式、表达习惯大相径庭。我在翻译《20世纪中国戏剧史》时,充分意识到英汉两种语言在表达上的诸多差异性,在翻译实践中综合运用各种中西翻译理论,诸如“功能对等理论”“目的论”“译者主体论”“操控论”以及严复老先生的“信、达、雅”翻译三原则等,尽力使译文贴切于原著,忠实、顺畅而不机械、生硬。

在翻译过程中,我会遇上政治生态、文化生态、传统道德伦理、生活习俗等方面的因素。原文中某些表述,若直译,有可能言不达意,目的语读者会比较迷茫,不知所言。事实上某些词汇,具有词汇意义与文化意义两种功能,而词汇的文化功能在不同的民族中所涵括的意义是有差别的。譬如英语词“red”,在词汇意义这个层面上,在东西方表示的是一种“颜色”,没有差异性;但它在文化意义就有天壤之别。“红色”在西方人眼里,象征着“暴力、血腥、糟糕”等。如“red deficit”(“财政赤字”)、“red score”(“考试没及格”),有的西方政客把中国共产党领导下的“red army”视为洪水猛兽,污蔑为“赤匪”等等。但在中国的文化传统中,“红色”代表着“吉祥、喜庆、团圆”,结婚用“红双喜”图案贴窗花、布置婚房,小孩压岁钱用“红包”装,公司给员工额外奖励也用“红包”。

三

基于英汉两种语言诸多不同的表达方式与语言习惯,我在处理这些差异点时大多采用翻译理论中的“归化法”(domestication),顺应西方读者的阅读与欣赏习惯,使译文具有较强的可读性。下面是笔者在翻译该书时遇上的较普通,但较具代表性的案例。

新中国成立后,中央政府鼓励知识分子以及各行各业人员做到“又红又专”。这个口号自20世纪50年代至20世纪70年代末我念大学时,在各种宣传材料、书籍、杂志上,这个词汇的译文是一致的:“To Be Red and Expert”。在我们的政治生态中,“红”代表着“热爱党、热爱国家,全心全意为人民服务”,实际上这个译文没有把“red”的内涵表现出来。较合适的行文应该是这样:To be socialist-minded and professionally proficient。

原著中,京剧《沙家浜》里的新四军连长带领伤员在沙家浜养伤,赞叹太湖周边是块“鱼米之乡”。由于中国人几千年来都是深受农耕文化的影响,盛产“稻米与鱼”的地方就称为“鱼米之乡”。中国翻译家也理所当然认为是这样的,就直译为:A land abundant in rice and fish. 可是,西方在古代没有像中国那样高度发达的农业,他们很大程度上过着像匈奴人那样的游牧生活。因此,在西方人眼里的“鱼米之乡”就是:A land flowing with milk and honey.

漢语中的文化典故源于我们传统的文化生活,但许多生活与文化现象是全人类所共有的,发生在西方的有些事件与故事有时不免与我们的相类似。如越剧中的《梁山伯与祝英台》,讲的是一个美丽而凄婉的爱情悲剧,代表古代中国人对爱情的追求与向往,同时也体现了中国人的审美取向。无独有偶,几百年前的意大利也有一出反对封建礼教、崇尚爱情自由的悲剧故事,这个故事被欧洲文艺复兴时期英国大剧作家莎士比亚写成剧本《罗密欧与朱丽叶》。国内学者将“梁祝”剧翻译为“Butterfly Lovers”,意思为《蝴蝶恋人》,这会让老外与西方的歌剧《蝴蝶夫人》的情节产生不必要的联想。因而笔者将它翻译为“Chinas Romeo and Juliet”,这样让外国读者把这个中国戏剧与他们所熟悉的故事情节联系起来,容易让他们接受这个来自东方的故事。

有些源自我们中国人文化生活的习语,比如“吃醋”“绿帽子”等,它们源于日常生活事件,随之被人们根据情节的特征隐喻化后,转为代表同一类事物的委婉说法。因此,以上两个习语我们若直译为drinking vinegar与wearing a green hat,外国读者就难以明白其中的含义。我们要根据这类成语或习语的内涵,通过变通方法将其翻译为:to be jealous和to be a cuckold.

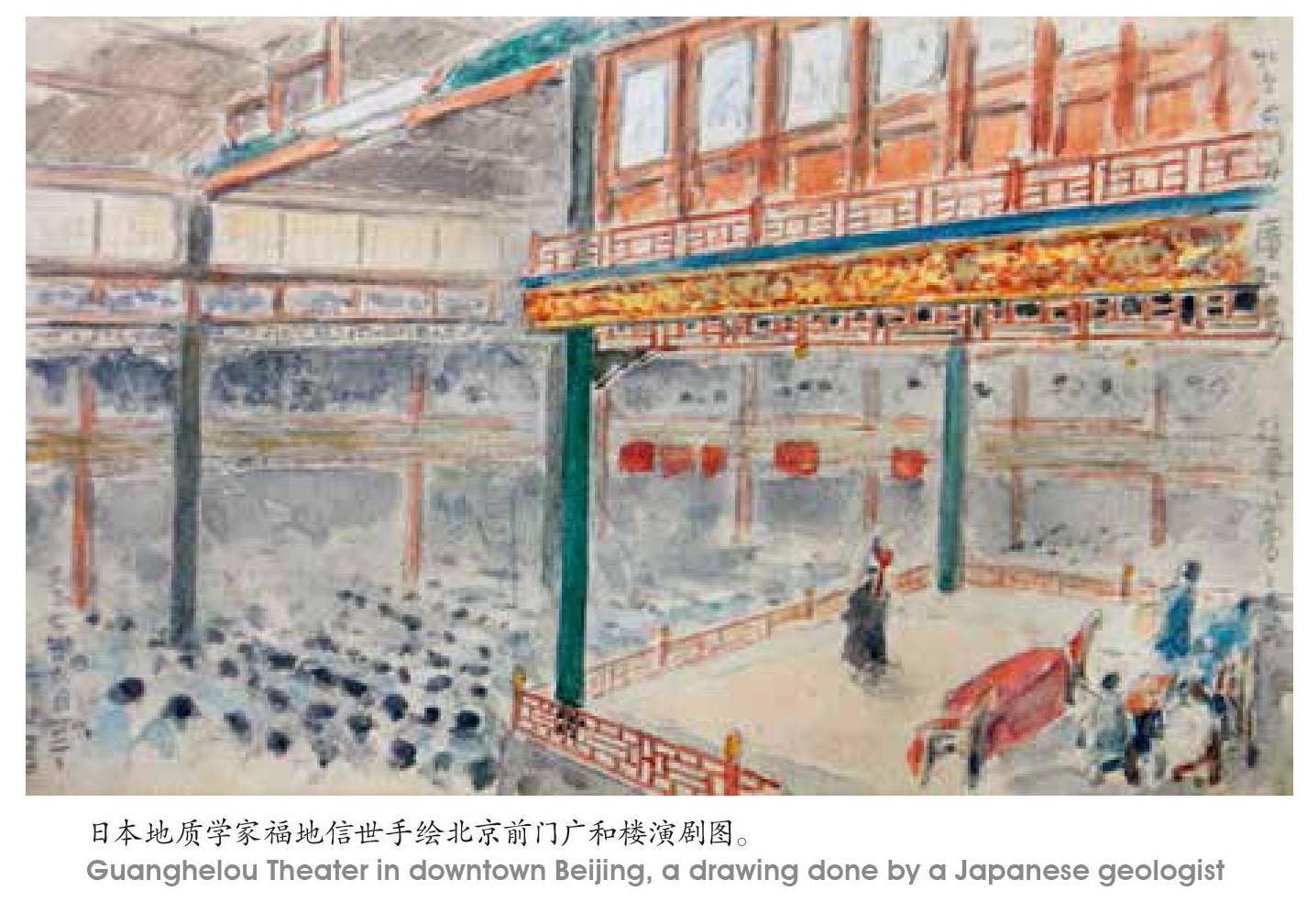

中国的戏剧源远流长,早在三千多年前的周朝,宫廷里就出现了专门为皇室表演的“俳优”。但中国戏剧的雏形要到北宋年间才确定,至元明时期达到第一个高峰。在随后的清代至20世纪,中国戏剧进入稳定发展的成熟期,形成了昆剧与京剧两大剧种以及200多个有地方性影响力的剧种和小剧种。各个主要剧种有其独特的专业术语,要把它们确切的内涵翻译出来并让国外同行看懂,是翻译这部戏剧史较难的部分,需要译者先查找相关材料弄明白后,经过一番推敲才能定下译文。

如“拆出戏”(selected episode)、“大同场”(grand full-length drama)、“关子”(ingenious suspense)、“老牌滑稽”(senior farce)、“勾栏瓦舍”(performing venue)、“话本”(scripts for story-telling)等,第一卷中有近1500个类似的术语。戏剧名称的翻译,有近半数不能望文生义,只有查找戏剧词典,了解其故事情节,才能按其内容翻译,如:《孽海花》(Romance between A Scholar and A Prostitute),《评雪辨踪》(Skeptical of His Wifes Virtue),《恨海难填》(The Tragedy of A Couple),《槿花之歌》(The Four Brothers of the Jin Family, Heroes of Resistant to Japanese Aggressors),《送女》(A Pearl Shirt)等等。全书谈及的剧本有2500部左右。

此次《20世纪中国戏剧史》英文版的出版发行,推进了中国戏曲的国际学术传播,深化了中外学术交流与对话。近年来,中国综合国力发展之快、对世界影响之大同样百年未有,中国正处于近代以来最好的发展时期。中国有许多传统的文化典籍与学术专著需要向国际社会介绍,以增强与中国经济繁荣相适应的影响力,让国际社会了解中国。美美与共,各美其美,从事翻译工作者的我们应有更多的责任与担当,需要我们更加努力,以水平更高的译文向世界介绍更多的中国文化。

Book One ofA History of Chinese Theater in the 20th CenturyTranslated and Published

By Zhang Qiang

I translated Book One of into English.

In July 2020, the English version of (1) was jointly released by Routledge and China Social Sciences Press. Book 2 is scheduled to be released in December 2020.

Background

Authored by Fu Jin, Professor of the National Academy of Chinese Theater Arts, the Chinese version was published in June, 2016 by China Social Sciences Press. The publication caused a big stir among scholars and the circles of theater in China.

The 2-book tome covers the 100-year period of the theatrical arts in China. It examines the century in two separate time capsules. The first explores how the theatrical arts began to transform themselves from 1900 to 1949, a turning-point when the Republic of China fell apart and the Peoples Republic of China came into being. The second part looks at how the theatrical arts evolved in the last 51 years of the 20th century.

Unlike some theater histories that illustrate concepts and works, Fu Jins magnum opus puts the evolution of Chinese theater in a broader perspective of Chinas modernization drive in the 100 years. It explores significant issues such as essential characteristics and patterns, achievements and lessons, tradition and development. It investigates the theater history in the vistas f politics, art and entertainment and looks at complex relations between tradition and modernity, Chinese characteristics and westernization, politics and arts, urban and grassroots theaters, concern with life and social ecology, shows and market.

What I Did

I was contracted to translate the book into English in 2017, one year after the release of the Chinese edition. To render this book into English successfully, I conducted a thorough research project. I read the original text from page to page, taking detailed notes and building a glossary. I then consulted reference books and relevant documents in order to find solutions to problems and difficulties in translation. In fact, I spent more time on researching and preparing than on translating. I aimed to recreate an English text that fully and accurately delivers what the author wants to say so that international researchers, theater professionals and scholars as well as common readers can easily and smoothly understand the traditional Chinese theater and the exchanges in Chinese theater between the east and the west.

The thorough researching and preparing was based on my understanding that it was a challenge to help promote cultural exchanges between Chinese readers and those who read English. Differences in worldview, ideology, political system, history, culture, tradition, social custom and life must be taken into consideration in order to deliver a readable English text. I know how English has evolved in different parts of the world and how some same English words and expressions present different meanings in different countries even though the language is an official language in these countries.

One big challenge I tackled in translating was the theatrical terms and play names that accumulated in the past 3,000 years. In the Ming (1368-1644) and the Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, there were over 200 kinds of regional operas across the country with Kunqu Opera and Peking Opera as the top two. Each of the major regional operas has its own system of theater terms. All of these terms add up to nearly 1,500. Moreover, I translated the titles of about 2,500 plays into English.

The publication of makes the academic book on Chinese theater available to overseas mainstream academic circles, promoting the international exchanges about Chinese theater and deepening exchanges and dialogs at an international level. In recent years, China has exerted unprecedented influence on the world as its comprehensive national power is increasing. I think this is the best time for translators to help share the Chinese culture with readers all over the world.