Knowledge of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) among healthcare providers:A cross-sectional study in Indonesia

2020-09-04KurniaFitriJamilWiraWinardiAmandaYufikaSamsulAnwarNurfanidaLibriantyNyomanAnandaPutriPrashantiTriNovitaWulanSariPrattamaSantosoUtomoTheresiaDwiameliaPutuPangestuCendraNathaSalwiyadiSalwiyadi1FebrivanWahyuAsrizal1IkramIkra

Kurnia Fitri Jamil, Wira Winardi, Amanda Yufika, Samsul Anwar, Nurfanida Librianty, Nyoman Ananda Putri Prashanti, Tri Novita Wulan Sari, Prattama Santoso Utomo, Theresia Dwiamelia, Putu Pangestu Cendra Natha, Salwiyadi Salwiyadi1,1, Febrivan Wahyu Asrizal1, Ikram Ikram1, Irma Wulandari1, Sotianingsih Haryanto1,1, Nice Fenobileri, Abram L.Wagner, Mudatsir Mudatsir, Harapan Harapan✉

1Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

2Medical Research Unit, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

3Tropical Disease Centre, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

4Department of Pulmonology and Respiratory Medicine, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

5Department of Family Medicine, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

6Department of Statistics, Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

7Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Public Health, Universitas Indonesia, Depok, West Java, Indonesia

8Bangli Hospital, Bangli, Bali, Indonesia

9Sungai Dareh Hospital, Dharmasraya, West Sumatra, Indonesia

10Department of Medical Education and Bioethics, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

11Panti Rahayu Hospital, Karangmojo, Yogyakarta, Indonesia

12Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Udayana, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia

13Department of Internal Medicine, Sanglah Hospital, Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia

14Department of Internal Medicine, Dr.Zainoel Abidin Hospital, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

15M Natsir Hospital, Solok, West Sumatra, Indonesia

16Dr H Yuliddin Away Hospital, Tapaktuan, Aceh, Indonesia

17M.Hatta Brain Hospital, Bukittinggi, West Sumatra, Indonesia

18Raden Mattaher Hospital, Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

19Faculty of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Jambi University, Jambi, Jambi, Indonesia

20Pariaman Hostiptal, Pariaman, West Sumatra, Indonesia

21Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

22Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh, Aceh, Indonesia

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS:COVID-19; Knowledge; Healthcare provider;Indonesia

1.Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was declared as pandemic on March 11, 2020, by the World Health Organization(WHO)[1].The earliest cases of COVID-19 were reported in December 2019 in Hubei Province of China when local health authorities reported several pneumonia cases of unknown etiology[2].Based on the COVID-19 Global Cases database[3], there were 665 616 confirmed cases and 30 857 reported deaths as of March 29,2020.The virus has high reproductive number (R0)[4]mainly because it has long incubation period[5,6], it is easily transmitted through human-to-human transmission via droplets and contact route[7,8],it persists on surfaces for a long time[9], transmission might occur from asymptomatic or presymptomatic cases[6,10], and there might be airborne transmission in some circumstances[11], although this is highly debated.Due to these reasons, COVID-19 has been reported in 177 countries as of March 29, 2020[3].

SARS-CoV-2 results in a syndrome leading in some cases to a critical care respiratory condition that requires specialized management at intensive care units (ICU)[5,12-15].A systematic review found that fever (88.7%), cough (57.6%) and dyspnea(45.6%) were the most prevalent clinical manifestations and decreased albumin, high C-reactive protein, and high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), lymphopenia, and high erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were the most prevalent laboratory results[16].Among 656 hospitalized patients, 20.3% required ICU,32.8% presented with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS),and 13.9% of had fatal outcomes[16].

In Indonesia, there were 1 155 confirmed COVID-19 and 102 deaths have been reported as of March 29, 2020[3].Indonesia is one of the countries with a high import risk estimate for COVID- 19[17- 19], and Jakarta, on Java island, and Denpasar, on Bali island, are the top two cities that have the highest risk[18].Moreover,a study found that the number of COVID-19 cases in the country was probably underdetected[19].Healthcare workers (HCWs) in Indonesia therefore need to be informed and knowledgeable to properly face the outbreak.This knowledge can be used not only to identify suspected cases but also to prevent health facility-related transmission.This study was conducted to assess the knowledge of COVID-19 among HCWs in Indonesia.This study is important to inform the government on the state of vigilance among frontline HCWs and to provide basic information to formulate strategies to manage the outbreak.

2.Materials and methods

2.1.Study design and setting

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 6 to March 25, 2020, in Indonesia to assess the knowledge of COVID-19 among HCWs, including doctors, nurses, and other staff.To recruit the participants, twelve hospitals were selected purposefully and stratified by Java-Bali and outside Java-Bali.Java and Bali were used as a sampling target because the two cities with the highest risk for COVID-19 outbreak, Jakarta and Denpasar, are located on those islands[18].The hospitals were also selected to include those located in capital city of provinces (an urban environment) and the capital city of regencies (a sub-urban environment).

2.2.Survey instrument

To assess the knowledge of COVID-19 among HCWs, a set of questions, developed based on existing facts from the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)[20]was used.The questionnaire assessed knowledge of transmission, symptoms,and prevention of COVID-19.The questionnaire also collected the characteristics of respondents, including sociodemographic,workplace, and professional details, exposure to COVID-19 information and training, and the local condition of COVID-19.The content of the questionnaire was evaluated by two medical microbiologists.The validity of questionnaire was tested among eleven HCWs with Cronbach's alpha 0.7, the minimal cut-off for good internal consistency[21].The questionnaire then was revised and finalized based on feedback from pretesters.

2.3.Data collection

Potential respondents were approached in hospitals and asked to participate in the study.Research staff provided a brief overview of the study aims, risks, and benefits.If the potential respondents were interested, they were asked to read and sign a written informed consent.While completing the questionnaire, respondents were given the opportunity to ask research staff about questions for clarification.

2.4.Study variables

The response variable in this study was the knowledge of COVID- 19 among HCWs.The questionnaire consisted of 13 questions assessing the knowledge on transmission, symptoms,and prevention of COVID-19.The possible responses to each question were “Yes” or “No”; a score of one was given for a correct response while zero for an incorrect response.For each respondent,the knowledge scores for each question were summed (i.e.ranged between 0 and 13) where higher scores indicated better knowledge.The levels of knowledge were then classified as good based on an 80% cut-off of this total score (i.e.a participant correctly answered at least 11 out of the total 13 questions).

Explanatory variables that could influence knowledge were collected and included demographic data, workplace characteristics,medical professional characteristics, exposure to COVID-19 information and training as well as the local condition of COVID- 19.Demographic data included gender, age, and marital status.Participants were grouped by age:those 30-year-old or younger and those more than 30-year old.For workplace characteristics, the respondents were asked:(a) the location of their current workplace(in Java-Bali or outside Java-Bali); (b) type of workplace (private or public hospital); (c) urbanicity of the current workplace (in the capital city of a regency (sub-urban) or in the capital city of a province (urban)); (d) department; and (e) the availability of protocol of triage and isolation for suspected COVID-19 patients.For professional characteristics, the respondents were asked:(a) their profession (doctor, nurse or others); (b) the length of medical experience (in years); (c) whether they were ever involved in any outbreak previously such as SARS, MERS, bird flu; (d) whether they have participated in any training course for dealing with COVID- 19 outbreak previously; and (e) whether they kept up to date on the latest information about COVID-19.In addition, the respondents were also asked whether confirmed COVID-19 case(s) had been reported either in their city or in their hospital.

2.5.Statistical analysis

In line with previous research[21-26], a two-step logistic regression was employed to assess the associations between the knowledge and the explanatory variables.In the first step, associations between knowledge and each explanatory were analyzed separately.In the multivariable analysis, to avoid loss of essential factors influencing knowledge, all explanatory variables with P≤0.10 in unadjusted analyses were included.A pre-assigned category for each explanatory variable was used as reference group and the estimated crude odds ratio (OR) and the adjusted OR (aOR) were interpreted in relation to this reference group.Significance was assessed at α=0.05 and analyses were conducted using Statistical Package of Social Sciences 17.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

2.6.Ethical approval

The protocol of this study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the School of Medicine, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh (041/EA/FK-RSUDZA/2020) and National Health Research and Development Ethics Commission (KEPPKN) of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia (#1171012P).Participation in this study was voluntary and participants received no financial incentive.Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

3.Results

3.1.Respondents' characteristics

Over the course of the survey period, the number of COVID-19 cases increased significantly in Indonesia.The survey, which was conducted in-person, was prematurely ended to reduce infection risk for study staff.During the survey, 297 HCWs completed the questionnaire in 12 hospitals across Java, Bali, and Sumatra.Nine respondents were excluded due to missing information leaving 288(97.0%) data included in the final analysis.

The participants' characteristics are presented in Table 1.The average age of the respondent was (31.5±7.4) years; almost 60% were aged 30 years or less and approximatively 65% were female.About 45% of the HCWs were working in the Java-Bali region and nearly equal percentages of surveyed HCWs were working in the capital city of regencies (51.4%) and provinces (48.6%).More than 75% of the respondents were working in public hospitals with an average length of medical practice of (6.8±7.6) years.In total, 75.0% of the surveyed HCWs stated that their hospitals had a protocol for triage and isolation for suspected COVID-19 cases.Less than 10% of respondents stated they were experienced in any outbreak prior to the survey, such as for SARS, MERS, bird flu, and diphtheria,and only 13.2% had participated in any COVID-19-related training course.Approximately 14.9% and 6.3% of the respondents stated there were confirmed case(s) COVID-19 in their city and their hospital, respectively.

Table 1.Unadjusted and multivariable logistic regression analysis showing predictors of knowledge about COVID-19 infection in general practitioners in Indonesia (good vs.poor) (n=288).

3.2.Knowledge on COVID-19 and associated determinants

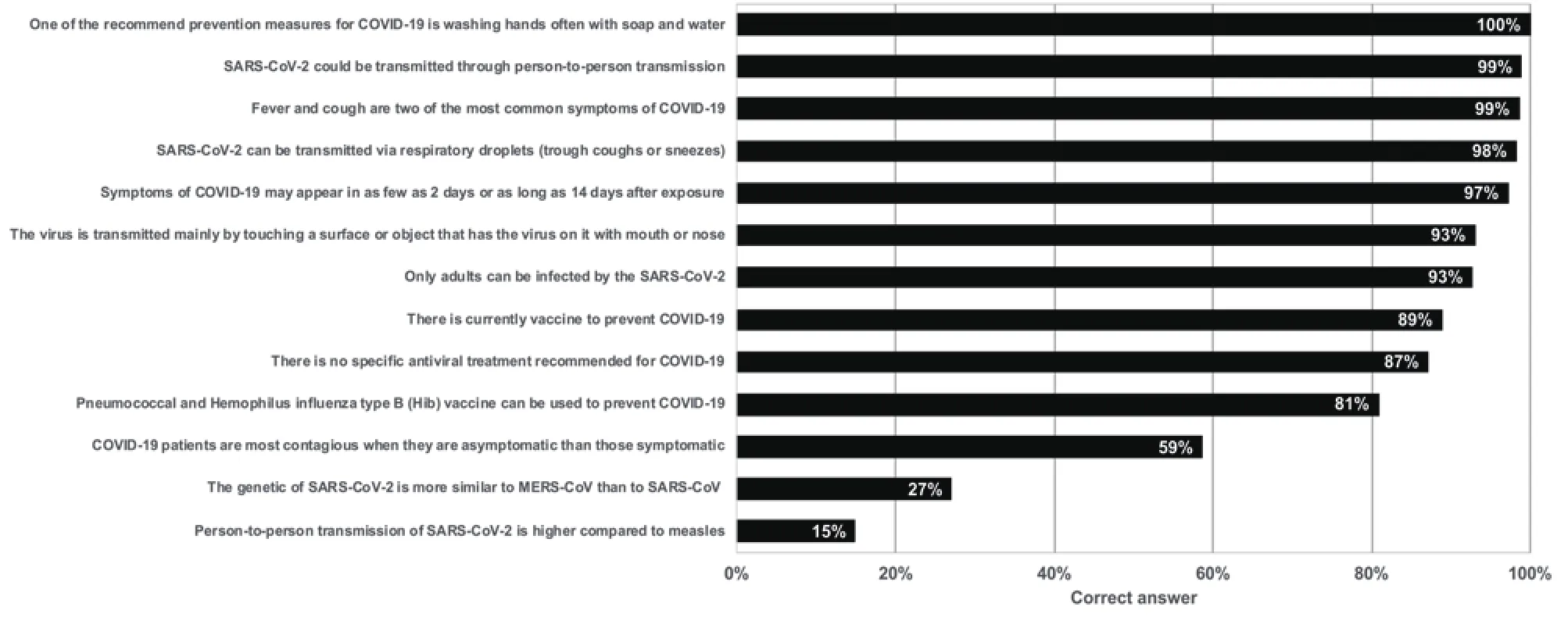

The mean and median score of knowledge of respondents was 10.3 and 11, respectively.Based on how we categorized the knowledge score, 149 (51.7%) of the surveyed HCWs had a good knowledge on COVID-19.Approximately 93% knew that one of the main transmission routes of SARS-CoV-2 was through touching the mouth, nose or eyes with contaminated hands and all respondents correctly answered that washing hands with soup and running water is one of the recommended measures to prevent COVID-19 (Figure 1).Although 87% and 89% of the surveyed HCWs mentioned that there was no specific treatment or vaccine for COVID-19, respectively, 85% of the respondents incorrectly stated that COVID-19 is more transmissible than measles and 41% incorrectly stated that the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is higher from asymptomatic COVID-19 patient compared to those who are symptomatic.

In the unadjusted analysis, gender, type of hospital, type of department, type of healthcare professional, and the length of medical experience were all significantly associated with knowledge.Having a confirmed COVID-19 in the city or in the hospital, having participated in any COVID-19-related training, and the availability of the protocol for triage and isolation for suspected COVID-19 were all not associated with the level of knowledge.Although the unadjusted analysis indicated that those who were working in public hospitals had better knowledge compared to those in the private hospitals, no association was observed after adjustment with other variables.

In the multivariable analysis, knowledge of COVID-19 was associated with type of healthcare professional, department and the length of medical experience (Table 1).Compared to doctors, nurses and other HCWs had lower odds of having good knowledge with aOR:0.38 (95% CI:0.20-0.72) and aOR:0.31 (95% CI:0.13- 0.73),respectively (Table 1).Those who have worked for more than 10 years also had reduced odds of good knowledge of COVID-19 compared to those who had medical practice experience of less than 5 years with the aOR:0.43 (95% CI:0.20-0.90).Respondents who were working in an infection department including respiratory departments had a better knowledge compared to those who were working in the emergency room, aOR:14.33; 95% CI:3.67-55.88.

4.Discussion

Adequate understanding of COVID-19 among HCWs is crucial to properly face the COVID-19 outbreak.Only with adequate levels of knowledge can doctors and nurses not only comprehensively identify, diagnose and manage the cases but also prevent the transmission of COVID-19 in healthcare settings.This study was conducted to assess how knowledgeable HCWs in Indonesia were of COVID-19.Our findings indicate that just over half of the surveyed HCWs had a good knowledge of COVID-19.This is not surprisingly because this is a new emerging infection and this study was started 4 days after the first two confirmed COVID-19 cases were reported in Indonesia[27].Although similar infections by coronaviruses have emerged and caused previous outbreaks, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Indonesia was not affected in a significant way.There had only been two probable SARS cases in the country[28]and no MERS cases[29].

Figure 1.Percent of correct response for each question used to measure the knowledge on COVID-19 among general practitioners in Indonesia (n=288).

One of the most important findings in this study was that the knowledge among HCWs who were working in the emergency department was lower compared to those in the infection department.This is especially worrying because HCWs in emergency departments are among the first group of HCWs to face suspected COVID-19 patients.Their lack of knowledge could contribute to COVID-19 patients not being tested or not being appropriately isolated.Therefore, efforts are urgently needed to improve this group, such as providing a short training course for not only doctors and nurses but for all HCWs.We also found that those who had longer medical experience (more than 10 years) were less knowledgeable about COVID-19.This finding could be because most of the information about COVID-19 comes from online and the younger generation is more familiar with using the Internet[30]and therefore has better access to COVID-19 information.A systematic review also found that longer experience in medical practice was associated with less knowledge[31].Because those with a longer medical practice are older, and the elderly have a higher risk for mortality from COVID-19[32,33], it is particularly important to inform older HCWs about COVID-19 and steps they can take to reduce their transmission risk.The need for this knowledge is highlighted by the fact that the number of deaths among HCWs in Indonesia has surpassed the number in China[34].

We hypothesized that exposure to the current COVID-19 outbreak such as having a confirmed case in the hospital or in the city would increase knowledge among HCWs as they may have better prepared themselves faced with this relatively personal risk.During the survey period, most of the confirmed cases were reported in Java and Bali,therefore we also hypothesized that those in Java-Bali would have better knowledge.However, our study found that none of these characteristics were associated with knowledge.This indicates a relatively homogeneous knowledge of COVID-19 across provinces of Indonesia and between those with and with exposure to previous diseases.The government should focus on enhancing the knowledge in areas where the outbreak is occurring.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution.The number of respondents was relatively low because the survey was ended earlier than scheduled due to health security reasons.Therefore, this study might not be representative for whole country but our study enabled us to highlight some important issues that need to be addressed.

In conclusion, knowledge of COVID-19 is low among HCWs in Indonesia during the early phase of the outbreak.Knowledge is relatively low among those who work in the emergency department,among nurses, and among those who have longer medical experience.Swift and structured strategies to enhance HCWs'capacities to respond to the outbreak are required for frontline healthcare providers.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to all hospitals that participated in this study.

Authors' contributions

KFJ, WW, AY and HH conceived and designed the study.NL,NAPP, TNWS, PSU, TD, PPCN, SS, SWA, II, IW, SH, and NF were responsible for data collection.SA and HH did formal analysis.ALW, MM and HH contributed to data interpretation.KFJ and HH drafted the manuscript.ALW, MM, HH, MM critically revised the manuscript.All authors have read the final manuscript.

杂志排行

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- COVID-19 and zoonosis:Control strategy through One Health approach

- Lymphopenia as a marker for disease severity in COVID-19 patients:A metaanalysis

- Performance and correlation of QuantiFERON-TB Gold, T-SPOT.TB and tuberculin skin test in young children with or exposed to tuberculosis

- Morphometric analysis of sand fly (Diptera:Psychodidae:Phlebotominae),Sergentomyia anodontis Quate and Fairchild, 1961, populations in caves of southern Thailand

- Soil-transmitted helminth egg contamination from soil of indigenous communities in selected barangays in Tigaon, Camarines Sur, Philippines

- Treatment for COVID-19 patients in Vietnam:Analysis of time-to-recovery