GAME OVER

2020-08-14

The controversy of wildlife consumption in Chinese cuisine and medicine

In the Chinese classic The Water Margin, when the outlaws of Liangshan try to take Daming city, heroes Xie Zhen and XieBao sneak past the guards disguised as hunters presenting wild game to noble lords.

This centuries-old dietary custom, controversial even in ancient history, is now officially ended: On February 24, Chinas National Peoples Congress adopted legislation banning the consumption of any field-harvested or captive-bred wildlife.

The change comes after years of campaigning by wildlife activists and medical experts on the environmental and health risks of Chinas wildlife trade. The masked civet, sold for meat in some markets in Guangdong province, had been identified as the intermediate host of 2003s SARS virus, and the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic has been linked with a seafood market in Wuhan where various species of exotic wildlife were being illegally sold as food.

The first definite record of wildlife consumption in China appeared 2,000 years ago. The Rites of the Zhou, a book on the customs of the Zhou dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE), states that the court chef was in charge of identifying and preparing food ingredients including “six birds (六禽), six domesticated animals (六畜), and six beasts (六獸).” Historians generally agree that the birds and beasts included elk, deer, bear, wild boar, wild goose, quail, pheasant, turtledove, and buttonquail.

Judging by historical records, wild animals could be found on ordinary tables as well. The QingbaiLeichao, an anthology of historiographical essays from the Qing period (1616 – 1911 CE), records many recipes involving wild animals, and snake was the most popular ingredient: “To go with liquor, cut the dried [snake] meat into round slices; eaten together with cat, its called ‘dragon-and-tiger; together with chicken, its called ‘dragon-and-phoenix.” Yexingchuan, a novel of the same era, even ranked the best wild game to eat: “Snakes are the most precious; rats come second; centipedes and sea-worm jelly come next.”

Scholar Lu Rong of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644) mentioned in his Notes on Shuyuan that officials in Xuanfu (in todays Hebei province) and Datong (Shanxi province) would offer local ground squirrels as tributes to the court. Qing scholar Yuan Mei praised the “uncommonly fresh” flavor of the masked civet, and detailed a dish in his Recipes from the Garden of Contentment.

However, the major reason for wildlife consumption in ancient times was food shortage. Usually, only royalty, officials, and rich families could regularly consume meat. According to the Guoyu, a historical record finished in the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 476 BCE), the emperor ate beef, mutton, and pork; princes ate beef, qing (high ministers) ate mutton, dafu (lower-ranked ministers) ate pork, shi (a social class between dafu and ordinary people) ate fish, and ordinary people only ate vegetables. When Song (960 – 1279) poet Su Shi was exiled to the island of Hainan, he wrote that the locals ate bats, toads, and rats because “it is very hard to get meat to eat” there.

Others preferred wild animals because it showed off high-end tastes. Qing dynasty scholar and gourmand Li Yu believed that wild animals that lived and moved freely in nature simply tasted better, writing “The meat of wild animals is not as rich as that of domesticated animals, but domesticated meat doesnt have the flavor.” Many wild animals were also prized as ingredients in traditional medicine: tiger bones were often used for healing fractures, rhinoceros horn could treat fever, and pilose antlers of young stags were made into a valuable tonic which is believed to nourish the kidney and activate blood circulation.

In Chinese cuisine, there were eight most prized food ingredients known as “Eight Treasures (八珍),” which were reserved for extravagant feasts. Though there were different versions of the list depending on times and regions, bear paw, deer tail, camel hump, and macaque head were often included (most of these have been listed as protected species since the late 1980s).

Even in ancient history, though, there were policies limiting or banning wildlife consumption. According to a historical record of the Zhou dynasty, in the 21st century BCE, Yu the Great, a legendary ruler of the Xia dynasty, forbade fishing in the third lunar month to allow fish and turtles to grow. In 1150 BCE, Emperor Wen of the Zhou dynasty issued a ban on harming all animals, with violators punished by execution. During the Ming dynasty, Emperor Renzong reprimanded officials who tried to collect the masked civet to present to the court, because it burdened the people and wasted money.

Ancient physicians also warned of the risk of wildlife consumption. In his Compendium of MateriaMedica, Ming physician Li Shizhen made a long list of wild animals unfit to eat, including peacocks, crows, mandarin ducks, snails, pangolins, jackals, weasels, and more. He pointed out that they could be harmful or even lethal to the body, alluding to cases of people poisoned after eating bats and toads.

During the SARS outbreak in 2003, Guangdong province, where the epidemic began, issued rules requiring people to “abandon the custom of eating wild animals” and protected species. But the same year, 12 government ministries including the State Forestry Administration published a “white list” of 54 terrestrial wildlife species that could be legally farmed and traded, including the masked civet. Thus, farmed animals of these species remained in markets and on restaurant menus.

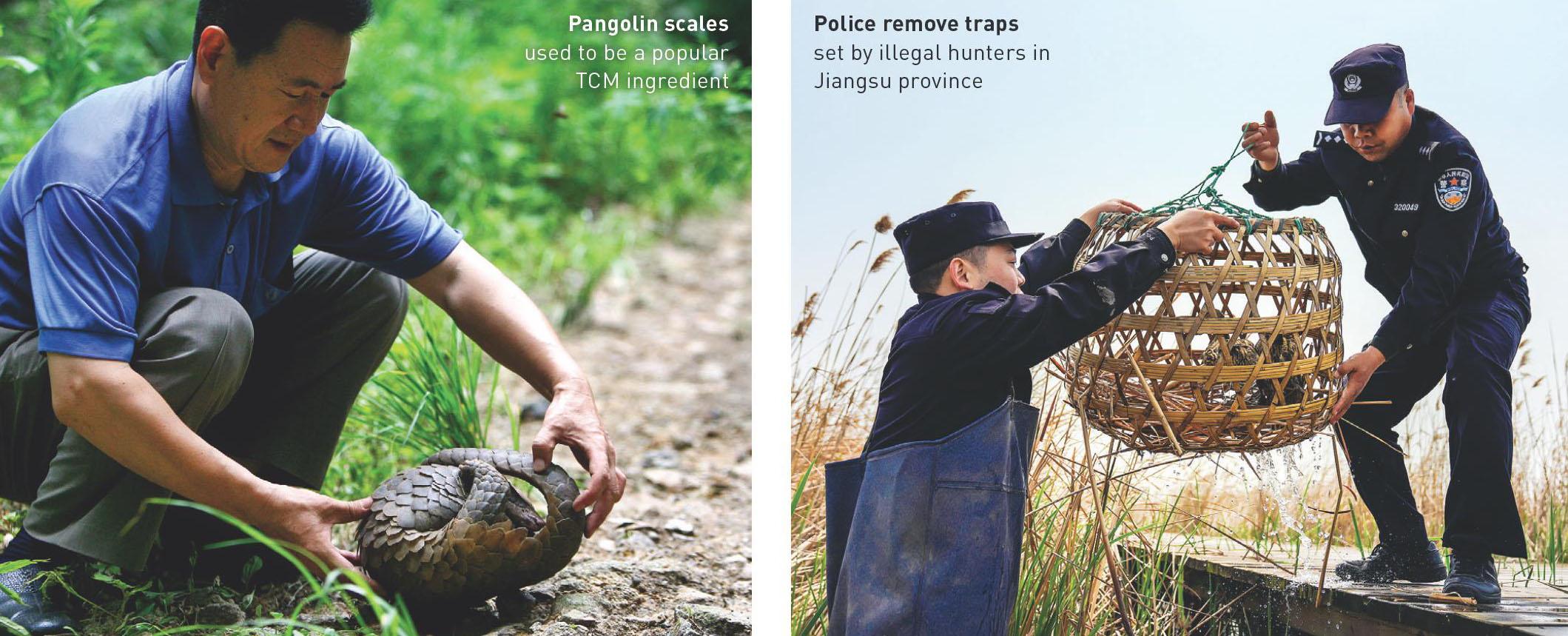

More optimistically, some policies were updated in 2020 to address the links between the wild animal trade and Traditional Chinese Medicine, closing a long-standing loophole in the legislation: In June, the pangolin was removed from the latest version of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia, the governments list of approved Chinese and Western drugs, meaning the endangered mammal can no longer be legally used as a TCM ingredient. Should more wild animals be taken off the list, it could be a sign of real change in attitudes—and not just laws—about wildlife. – SUN JIAHUI (孫佳慧)