诗歌教育的演进

2020-05-29高曙光

高曙光

詩歌的世界是无边无际的,在漫长的发展过程中,它也经历了起起伏伏。

难词探意

1. articulate /ɑ r t kjule t/ v. 清晰地发(音);明确有力地表达

2. crib /kr b/ n. 婴儿床;栅栏

3. lullaby / l l ba / n. 摇篮曲;催眠曲

4. strand /str nd/ n. 线;串

5. unsanctioned / n's k nd/ adj. 未批准的;未经认可的

6. marginalize / mɑ rd n la z/ v. 排斥;忽视;使处于社会边缘

7. reinvigoration /'ri:in,viɡ 'rei n/ n. 重新振作

The American poet William Stafford was articulating what many poets believe: that the roots of poetry (rhythm, form, sound) go far back—both personally and culturally— “to the crib” and “to the fire in front of the cave.”

No surprise, then, that children delight in the pleasures of lullabies, nursery rhymes, chants and jingles. Yet as they get older, their delight in poetry often fades. Their pleasure in language and form lessens.

How have schools been part of this evolution, and what can they do to bring back delight

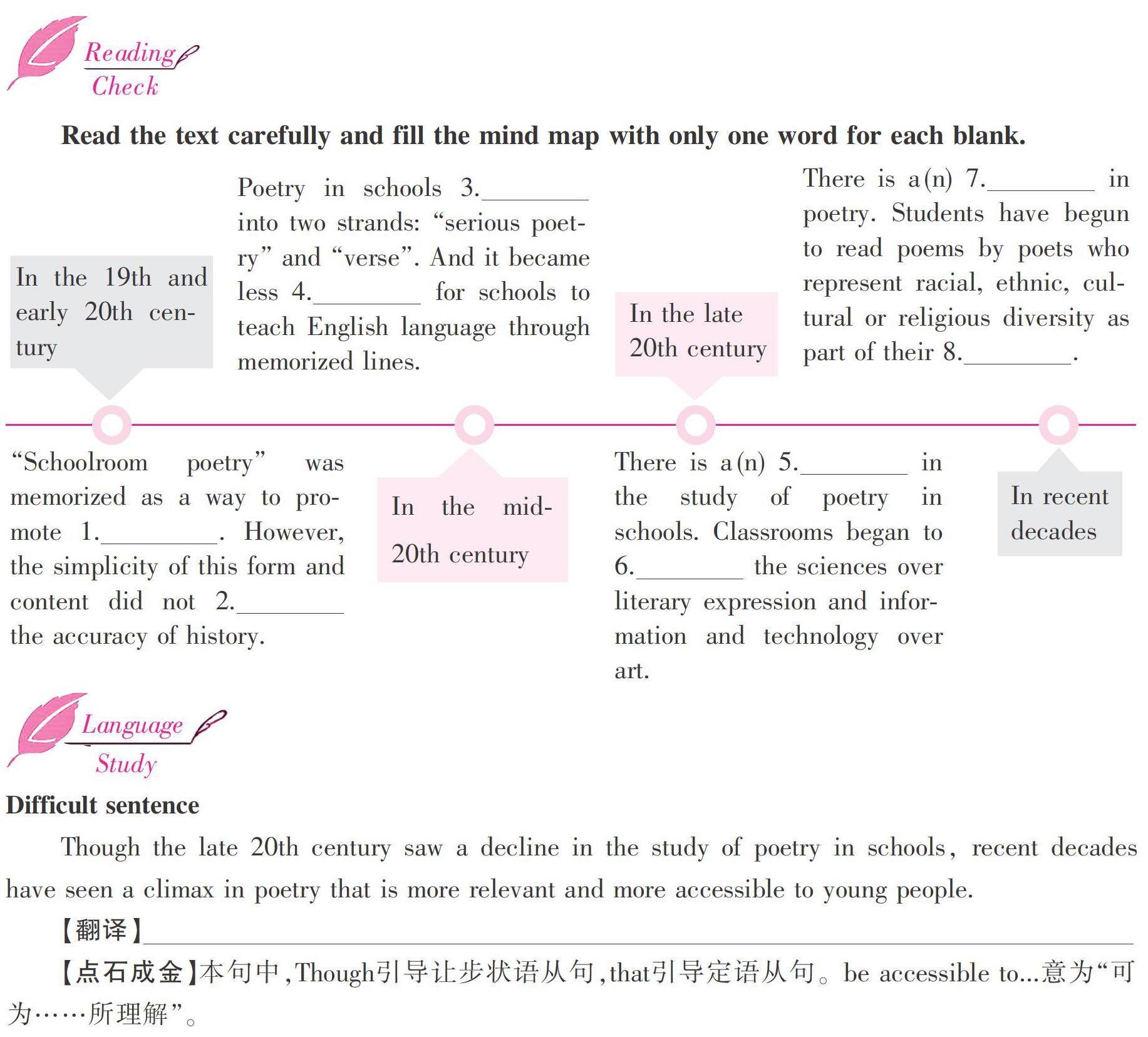

Historically, poetry has played an important role in the curriculum of U.S. schools. In 19th- and early 20th-century classrooms, “schoolroom poetry” was memorized and performed as a way to promote citizenship, to create a shared sense of community, to develop an American identity and to assist with language acquisition—particularly among immigrants. This ease of form and content was not, however, matched by historical accuracy. Writers sometimes rewrote history into poems that celebrated American values.

In the mid-20th century, it became less important for schools to make citizens or teach English language through memorized lines. Instead, poetry in schools separated into two strands: “serious poetry” and “verse.” Serious poetry was studied; Verse, on the other hand, was unsanctioned—playful, irreverent and sometimes offensive. It was embraced by children for the sake of pleasure and delight.

By the late 20th century, classrooms and curricula began to value the sciences over literary expression and information and technology over art. The study of any poetry—serious or not—became marginalized.

Though the late 20th century saw a decline in the study of poetry in schools, recent decades have seen a climax in poetry that is more relevant and more accessible to young people. For instance, if in the past, schoolchildren learned poems written almost exclusively by white men glorifying a sanitized version of American history, recently students have begun to read poems by poets who represent racial, ethnic, cultural or religious diversity as part of their heritage.

In addition to writing poetry in their classes, todays young writers are appearing on numerous poetry websites and are circulating poems – their own and those of others – through social media. As a poet, educator and scholar, I am heartened by the current reinvigoration of the field. Young people are growing their own voices, falling in love with words, writing and performing their own poems.