Availability of basic life support courses for the general populations in India, Nigeria and the United Kingdom: An internet-based analysis

2020-05-18AlexeiBirkunFatimaTrunkwalaAdhishGautamMiriamOkoroanyanwuAdesokanOyewumi

Alexei Birkun, Fatima Trunkwala, Adhish Gautam, Miriam Okoroanyanwu, Adesokan Oyewumi

Department of Anaesthesiology, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, Medical Academy named after S. I. Geor gievsky of V. I. Vernadsky Crimean Federal University; 295051, Lenin Blvd, 5/7, Simferopol, Russian Federation

KEY WORDS: Basic life support; Cardiopulmonary resuscitation; Courses; Training; India; Nigeria; United Kingdom

INTRODUCTION

The more people are trained in basic life support (BLS) in the community, the higher are the chances for bystander resuscitation to be commenced in a reallife emergency.[1]Efficient education of lay people in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is currently considered as a major determinant of survival in an outof-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA)[2]and set as a “primary educational goal in resuscitation”.[1]

Despite its critical importance, CPR training among the lay public is reported to be limited in many communities worldwide.[3-7]With that, little is known about the existing real opportunities for lay people to get trained in BLS in different countries.[8,9]

Exploratory investigations of available courses for BLS training, in terms of their quantity, geographical distribution, organization and cost, may help to determine national patterns, trends and weaknesses in training general public, and to set respective priorities for improving public CPR education and, consequently, resuscitation outcomes in cardiac arrest victims.

This study aimed to investigate availability, accessibility and characteristic features of BLS courses offered to the general public of India, Nigeria and the United Kingdom (UK).

METHODS

This was a cross-sectional study, with a singleday search using the Google engine. The countries for the study were selected based on the investigators’ citizenship. The country-specific search, eligibility screening and data collection processes were headed by investigators holding respective citizenship (India – AG, Nigeria – MO and AO, the UK – FT), and verifi ed by non-national investigators. The search was executed in English, being the official language and the default language of online activity in all three countries.[10]

Keyword selection

First, a source list of English keyword combinations, comprising 42 pairs of resuscitation and education terms, was mutually agreed by the investigators. Further, mean yearly popularity indices (December 2017–November 2018) were calculated for the combinations by country based on the Google Trends data. Top three keyword pairs for each country, produced a total of five unique search combinations: “first aid courses”, “first aid training”, “emergency courses”, “emergency training” and “CPR training”. Being less popular, the following combinations were still considered thematically relevant and were included into the final list at the discretion of investigators: “CPR courses”, “BLS training”, “BLS courses”. Finally, all selected keyword combinations were supplemented with respective country name: “India”, “Nigeria”, or “UK”.

Search

The search was conducted on December 14, 2018. Before searching, all browser (Google Chrome) history, was cleared, including cache and cookies. Then, respective country was selected in the Google search settings. For every search, only first 100 consecutive links (excluding ads) were reviewed, considering it is unlikely that the majority of people will review more results for a single search. Judging from the title and short description on the results page, obvious irrelevant links were excluded at this stage. Remaining links were cleared from duplicates and extracted for subsequent eligibility screening.

Inclusion criteria

A course description webpage resulting from each source link was reviewed to confirm course eligibility, applying the following criteria: the course is devoted to BLS, or contains BLS as part of a syllabus; the course is suitable for any adult layperson, irrespectively of their baseline knowledge, educational level and occupation (including unemployed); for classroom and blended learning approach, the on-site training is provided within the territorial boundaries of the respective country; the course is provided on an ongoing basis, and the participation proposal is active at time of the search.

Throughout this paper a “course” refers to a training program. Stand-alone videos, texts, photos, pictures were not considered to be courses, and were excluded. Both adult and pediatric BLS courses were screened for eligibility. Whenever multiple potentially eligible courses were found following the source link, all these courses were considered for inclusion.

Data collection

For eligible courses, the following data were searched on respective course description web pages and tabulated for subsequent analysis: course name, course organizer name and organizational form, teaching method (classroom, distance, blended), instructors (as declared by organizer), group size, training duration, cost per trainee, presence of automated external defibrillator (AED) training and knowledge/skills assessment in a syllabus, declared concordance with national or international CPR guidelines, certification of trainees and course geography. In the cases where information of interest was missing on the primary course description webpage, additional pages of the website were reviewed to retrieve necessary data. For harmonization purposes, geographic locations of the courses were further arranged according to the first-level administrative country subdivision.[11]

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed descriptively and presented as frequencies, percentages, and means. Costs in national currency were converted to US dollars according to the conversion rates as of December 14, 2018 (www.xe.com).

RESULTS

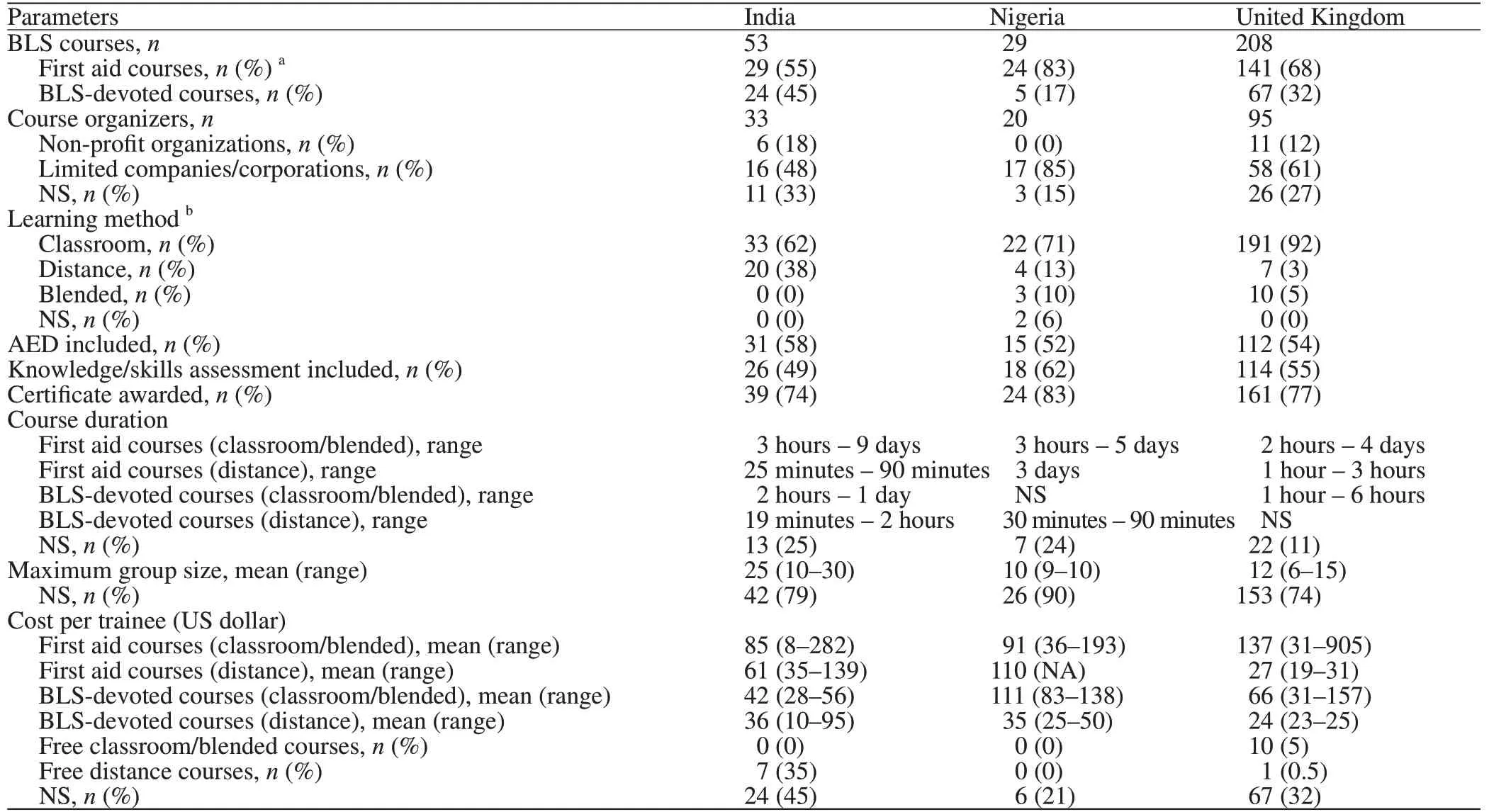

After excluding irrelevant links and duplicates, all potentially eligible websites were reviewed, producing a total of 53, 29 and 208 courses for India, Nigeria and the UK, respectively (Figure 1). The number of eligible courses proposed by a single organizer varied from one to eight. Main characteristics of the BLS courses included in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Study fl ow chart.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of the on-site BLS training courses in India by the fi rst-level administrative subdivisions. *: some courses are provided in multiple administrative subdivisions. NCT: National Capital Territory.

Figure 3. Geographical distribution of the on-site BLS training courses in Nigeria by the fi rst-level administrative subdivisions. *: some courses are provided in multiple administrative subdivisions. FCT: Federal Capital Territory.

Figures 2–4 show geographical distribution of the BLS courses with on-site training (classroom or blended learning method) by country. Maximum number of settlements where a particular course is offered reached 4 for India, 11 for Nigeria and 58 for the UK.

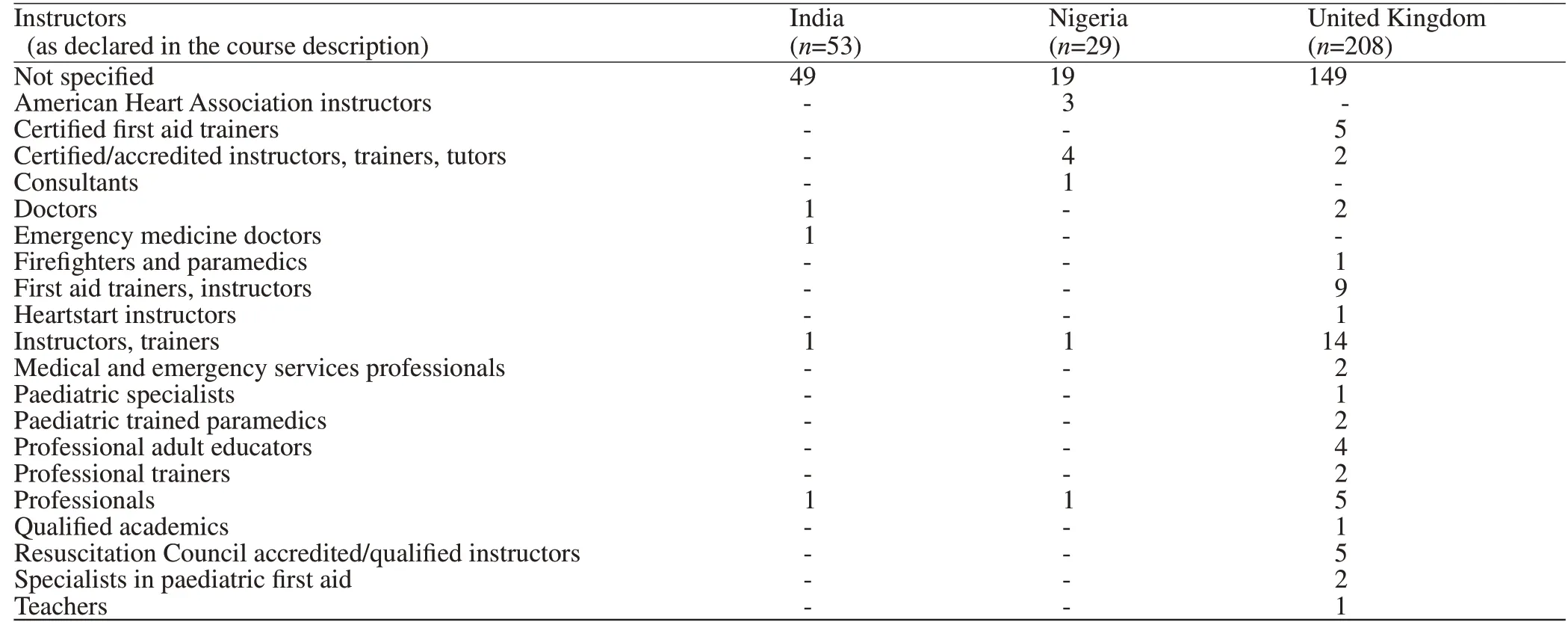

Tables 2–3 present data on conformity of the course syllabus with national or international CPR guidelines (Table 2) and on instructors’ qualifications (Table 3) as declared by the organizers in the course description.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we attempted to reconstruct the process that a layperson may use to find and access basic CPR courses in India, Nigeria and the UK.

The country-specific internet-search in English revealed significantly fewer web-based propositions for attending BLS courses in India and Nigeria when compared to the UK. With the population of India and Nigeria, respectively, 20 times and 3 times higher the size of the UK’s (Table 4), there are 4 and 7 times less unique offerings to get trained in CPR. Alongside this, the number of BLS courses per 10 million inhabitants is calculated to be 0.4 for India, 1.5 for Nigeria, and 31.5 for the UK, suggesting that the population coverage with BLS training in India and Nigeria is, respectively, 79 and 21 times lower compared to the UK, while in India it is 3.7 times lower than in Nigeria.

Figure 4. Geographical distribution of the on-site BLS training courses in the UK by the constituent countries and the crown possessions. *: some courses are provided in multiple constituent countries.

Besides the paucity, the search-derived opportunities for BLS training in India and Nigeria have a greatly limited and uneven geographical distribution. In India, the on-site CPR training for lay people is arranged in 8 of 29 (28%) states and 1 of 7 (14%) union territories (integrally 25% of the first level administrative country subdivisions). With that, about one fourth are located within the single state of Maharashtra. In Nigeria, BLS training is offered on-site in 11 of 36 (30%) states and in the Federal Capital Territory (in total 32% of the first level administrative country subdivisions), and more than one third of the trainings are organized in the state of Lagos. In the UK, the on-site BLS training is proposed in all constituent countries. Being most prevalent in England (73% of all UK’s courses), the training proposals are less distributed in Wales (14%), Scotland (8%) and Northern Ireland (2%). Additionally, the search revealed two BLS courses (1%) for one of the crown dependencies (Isle of Man), and no results were yielded for the British Overseas Territories. We suppose, additional offerings of the on-site CPR training may be found when performing the country-specific and territory-specific search, rather than searching for the UK in whole. Further, the UK search produced the highest number of on-site training courses with locations unspecifi ed (n=21).

Many characteristics of the CPR courses exhibit the similar trends for India, Nigeria and the UK. Course organizers are predominantly business entities, whereas the proportion of the non-for-profi t providers is generally less than one fifth (for Nigeria – 0%). BLS is mainly taught as part of the fi rst aid courses, with exact duration of the CPR training unspecified in the course syllabus. As declared by the organizers, about 50%–60% courses involve AED training, as well as some assessments of knowledge and/or skills. Over 70% award a certifi cate on completion of a course.

Table 1. Characteristics of the BLS courses by country

Table 2. Concordance of the course content with the guidelines for CPR

The prevailing learning method is a classroom training. Distance learning was most commonly found in the search results for India, being less frequent among the courses for Nigeria and the UK. Few courses for Nigeria and the UK are utilizing a blended learning approach.

The courses are highly variable in their declared duration (from 19 minutes for distance learning to 9 days for classroom training), maximum size of the training group (6–30 trainees), instructor qualifications and cost of participation. Mean cost per trainee for attending an on-site course (classroom or blended) in India and Nigeria (Table 1) is generally exceeding the monthly minimum wage per country (Table 4). With that, our search revealed no free of charge courses with on-site training for laypersons in India or Nigeria. As for the UK, about 5% of the on-site training courses are offered for free.

Information on conformity of the course content with national or international CPR guidelines is commonly missing from the course description. Where indicated, American Heart Association guidelines are most frequently declared for India and Nigeria, and guidelines of the Resuscitation Council (UK) for the UK. Further, there are instances where courses are declared to be concordant with outdated guideline editions.

Recent investigation of availability of BLS training for lay people in the Russian Federation revealed 55 webbased proposals to get trained,[9]exhibiting a profi le close to that of India and Nigeria in the present study. The vast majority of the Russian-language courses include BLS as a component of the first aid training program and utilize an on-site training approach. About 95% of the courses are paid. The courses are highly variable in the duration of training (1–36 hours), number of trainees per group (4–18 persons) and instructors’ qualifi cations. Geographical distribution of the courses is limited to 30 cities, corresponding to less than 2% urban settlements of the Russian Federation. Moreover, more than 80% of onsite courses are concentrated in the two cities – Moscow and Saint Petersburg.[9]

We suppose the paucity of CPR courses in India, Nigeria and Russia can be explained by relatively low demand of the populations for the BLS training, that, in turn, is attributable to the low personal income, insufficient awareness of the relevance of CPR training for lay people, and basically a lack of administrative regard and governmental control of community CPR training.

Table 3. Course instructors’ background and qualifi cations

Table 4. General characteristics of the countries under study

From among the countries under study, the UK demonstrates the highest rates of community CPR training and bystander resuscitation, comparable to those in other developed nations.[16-18]Recent survey revealed that almost 60% UK adults have ever received CPR training and 22% were trained in defibrillator use.[19]Of those trained in CPR, 53% completed their training at workplace.[19]The proportion of bystander-witnessed OHCA, where bystander CPR was given is 61% in England.[20]For Scotland, the rate of bystander CPR was reported to be 52% in 2007, demonstrating sustainable growth.[21]

The published data on epidemiology of OHCA and community CPR training are extremely limited for India and Nigeria. The survey of bystanders who witnessed OHCA and brought the victims to emergency departments in Kerala (India), showed that only 8 (2%) of 350 respondents performed bystander CPR before arrival to hospital, and lack of CPR training was reported as the most common reason (98%) for nonperformance of CPR in this study.[22]Krishna et al[6]investigated outcomes of CPR among 80 adult patients with OHCA in India, revealing bystander CPR rate of 1.3%. The authors highlighted urgent need for starting national initiative to improve bystander CPR rates and survival of OHCA events, including education of lay public in basic CPR.

We have found no publications reporting actual bystander resuscitation rates in Nigeria. Several studies from Nigeria showed null previous training and poor BLS knowledge among secondary school students[23]and school teachers,[24]as well as inadequate knowledge and sparse training in CPR among the healthcare professionals.[25,26]

Additional studies are required to investigate the existing proportions of the general public that have undergone BLS training in India and Nigeria, as well as to understand the populations’ attitude, willingness and barriers to get trained in CPR. This information may help to plan and implement targeted and resource effi cient interventions. Future studies are also deemed to be necessary to investigate the quality of available CPR education.

Low survival from OHCA, supported by low bystander CPR rates in developing countries necessitate immediate actions to increase availability of BLS training for lay people.[6]Use of alternative modalities of teaching BLS, including blended learning, self-instruction programs and peer-led training, may help to improve access to CPR training and satisfy the needs of various types of learners.[1]Another important way to boost the rates of bystander resuscitation is to include compulsory CPR training into school curriculum,[1]that hopefully will be achieved in the UK by the year of 2020,[27]but is yet to attain success in India[28]and Nigeria.[23,24]

Limitations

This study utilized the global country-level terms (India, Nigeria, the UK) to designate the search geography, thus possibly limiting the number of relevant resources identifi ed. Additional investigations by country subdivisions may advance the search precision and reveal more potentially eligible web-based proposals to get trained in BLS. Future studies are warranted in this direction.

Besides the English language search, additional search in Indian and Nigerian languages could bring more potentially eligible results.

Sources of information other than the internet (e.g., television, radio, newspapers, brochures) may potentially be utilized by organizers to advertise BLS courses. Searching these media, might reveal additional opportunities for CPR training within the studied countries.

Considering the dynamic nature of the internet, a repeated search utilizing the same methodology may produce different results, yet it is still unlikely to infl uence the conclusions.

This study explored BLS training courses offered for a lay person for voluntary participation, whereas local practices of BLS training at place of work or place of education were out of the scope of the study, limiting the generalizability of our results.

Relevant information (e.g., course participation cost, course duration, geography) was frequently missing from the course description. It cannot be ruled out, that factual evidence might have an effect on results and conclusions of the study.

CONCLUSIONS

Based on the internet search, in contrast to the UK, the opportunities to get trained in BLS for a lay person in India and Nigeria are extremely limited: available courses are few, uneven in their geographical distribution, expensive, and highly heterogeneous in organization and methodology. Being currently neglected, alternative methods of training, and BLS teaching in schools can increase the accessibility of highquality public CPR education. The study design can be utilized for investigating patterns of resuscitation training in other countries and communities.

Funding:This study did not receive any funding.

Ethical approval:Not needed.

Conflicts of interests:The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributors:AB determined the concept of the study and was a major contributor to the study design, data analysis, interpretation and manuscript production. FT, AG, MO and AO substantially contributed to the design, data collection and analysis, and assisted in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the fi nal manuscript.

杂志排行

World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- The importance of visualization of appendix on abdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of appendicitis in children: A quality assessment review

- Clinical characteristics and prognosis of communityacquired pneumonia in autoimmune diseaseinduced immunocompromised host: A retrospective observational study

- The life-saving emergency thoracic endovascular aorta repair management on suspected aortoesophageal foreign body injury

- Effects of intracoronary injection of nicorandil and tirof ban on myocardial perfusion and short-term prognosis in elderly patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction after emergency PCI

- Morbidity and mortality risk factors in emergency department patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia

- Prognostic value of intracranial pressure monitoring for the management of hypertensive intracerebral hemorrhage following minimally invasive surgery