Plastic bronchitis associated with Botrytis cinerea infection in a child: A case report

2020-04-08YanRuLiuTaoAi

Yan-Ru Liu, Tao Ai

Yan-Ru Liu, Tao Ai, Department of Pediatric Respiratory Medicine, Chengdu Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital, School of Medicine, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, Sichuan Province, China

Abstract BACKGROUND Plastic bronchitis (PB) frequently occurs in children after the surgical repair of congenital cardiac defects or in the presence of inflammatory or allergic diseases of the lung. Accurate epidemiological data of this condition are still lacking.CASE SUMMARY A 5-year-old boy, with a clear medical history, presented to our hospital with persistent cough and pneumonia with segmental atelectasis on chest computerized tomography. He showed no significant improvement after 1 wk of amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium treatment. Bronchial casts were extracted using flexible bronchoscopy. Pathological examination of the dendritic cast confirmed the diagnosis of type I PB. Botrytis cinerea was detected by next-generation sequencing of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. After the removal of the airway obstruction and fluconazole treatment, the patient recovered and was discharged 14 d after admission without the recurrence of cough.CONCLUSION Botrytis cinerea pneumonia should be considered in children with PB who still have prolonged cough and atelectasis after a regular course of antibiotic therapy.Flexible bronchoscopy and etiological examination should be performed in a timely manner to determine the diagnosis, clear the airway obstruction, and target etiological treatment.

Key Words: Bronchial casts; Botrytis cinerea; Pneumonia; Children; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Plastic bronchitis (PB), which has been described many times, is characterized by the formation of bronchial casts in the airways for undefined etiology, resulting in bronchial obstruction, ventilation and gas transfer dysfunction, and respiratory and circulatory failure[1]. Although some reports have described PB in pediatric patients,such as PB withMycoplasma pneumoniaeinfection, influenza virus infection, adenovirus infection, asthma, and lung transplantation[2-6], reports of PB withBotrytis cinereainfection in humans are scarce in the literature.Botrytis cinereais considered an endophytic fungus that can cause disease in many fruit, flower, and leafy vegetable crops; it has no apparent host specificity and can infect more than 1000 plant species[7].Botrytis cinereais known to actively promote plant susceptibility by employing a variety of virulence factors[8]. To our knowledge,Botrytis cinereahas potential risks affecting human health[9]. We herein report a pediatric case withBotrytis cinereainfection associated with PB, and summarize its clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment, in the hope of providing new ideas for the etiological diagnosis and treatment of PB.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 5-year-old boy was hospitalized for persistent cough for 4 mo.

History of present illness

The patient’s parents reported the occurrence of recurrent cough over the past 4 mo,without hectic fever, expectoration, hemoptysis, night sweats, weight loss, or wheezing. Initially, the patient was diagnosed with cough-variant asthma in the outpatient department because of his impulse oscillometry examination result, which showed that the response frequency was 22.26 Hz before inhalation and decreased by 8.09% after inhalation. The intradermal allergen tests were positive for dust mites (++)and mycetes (++). He was treated with inhaled corticosteroid therapy for 3 mo, but his cough did not improve significantly.

History of past illness

The patient had a clear medical history, without allergies, eczema, or repeated wheezing. He had already received vaccines for bacillus Calmette–Guérin, hepatitis B,diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, and epidemic encephalitis B.

The patient lived with his parents since birth and was oriented to his parents. There was no history of psychological stress or substance abuse. There was no family history of hereditary disorders.

Physical examination

The patient had a body temperature of 36.2 °C, heart rate of 95 beats/min, respiratory rate of 27 breaths/min, blood pressure of 92/63 mmHg, and SpO2level of 98%. He was conscious, able to answer age-appropriate questions accurately, breathing slightly faster, and without circumoral cyanosis. He had bilateral grade 2 tonsils without exudate, no nasal discharge, and no conjunctivitis. His skin was warm and moist,without any lesions. The breathing sounds were rough in both lungs without moist rales or wheezes. No arrhythmia, enlargement of the liver and spleen, or palpable abdominal lump were observed. Physical examination of the nervous system showed no obvious abnormality. No signs of abuse were observed.

Laboratory examinations

The complete blood cell count test showed all components to be within the normal range, with the exception of increased eosinophils (10.5%). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and blood biochemistry parameters (including analyses of arterial blood gas, electrolytes, liver enzymes, creatinine, myocardial enzyme, and lactic acid)were normal. Serological testing for pathogens gave negative results for hepatitis viruses A, B, and C, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella virus, tuberculosis,Toxoplasma gondii, human immunodeficiency virus, varicella-zoster virus,Treponema pallidum, respiratory syncytial virus, coxsackievirus,Legionella pneumophila,Mycoplasma pneumoniae, adenovirus, influenza viruses A and B, parainfluenza virus,and Epstein–Barr virus. Blood autoantibodies and tuberculin skin tests showed negative results. Tests for humoral immunity showed normal results.

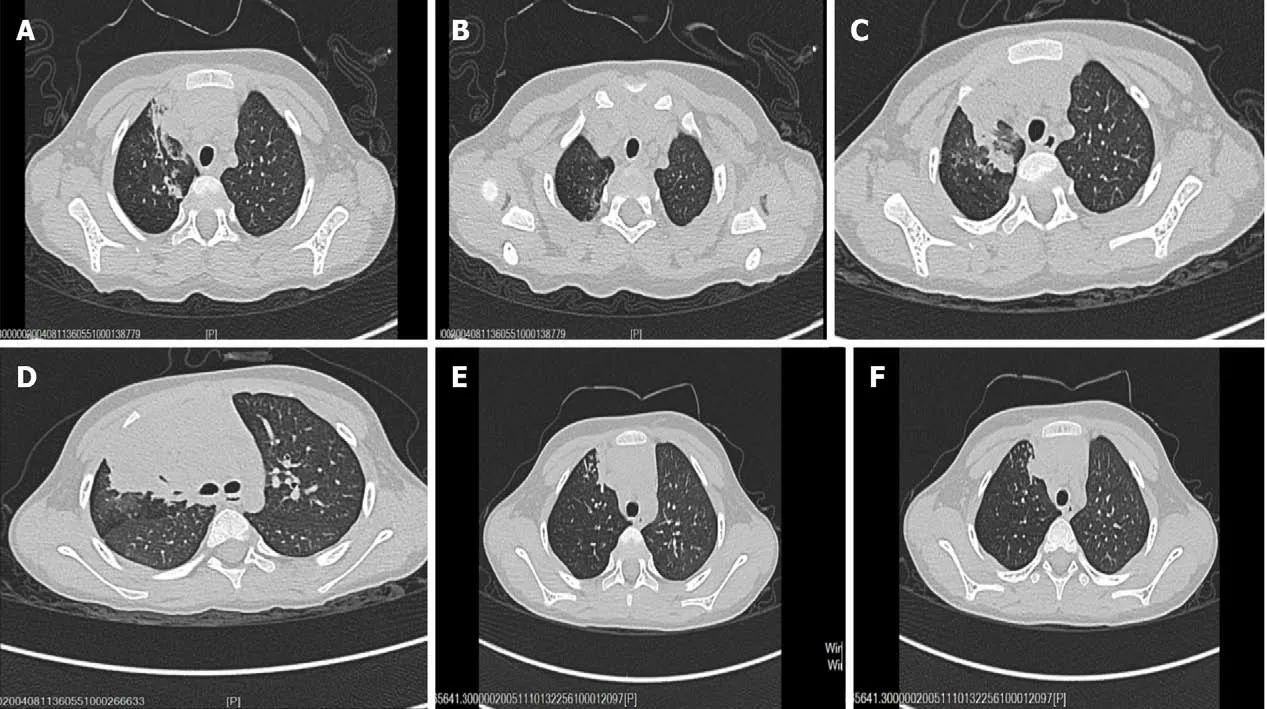

Imaging examinations

Chest computerized tomography (CT) showed right upper lobe pneumonia with segmental atelectasis (Figure 1A and B). Abdominal ultrasonography findings were normal. Electrocardiogram results were normal. Accordingly, our first clinical consideration was lobar pneumonia, and treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (iv 30 mg/kg once every 8 h) was initiated after sputum culture and blood culture were completed.

Further diagnostic work-up

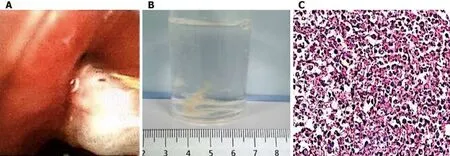

During hospitalization, the patient developed expectoration and had no significant improvement in cough symptoms. One week after treatment, although blood culture and sputum culture tests showed negative results, repeat chest CT results showed that the inflammatory lesions in the right upper lung were expanded and new lesions appeared in the right lower lung (Figure 1C and D). The patient was evaluated further by flexible bronchoscopy, histopathology examination, and next-generation sequencing of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Serological tests for schistosomiasis,lung flukes, cysticercosis, liver flukes, metacercaria,Trichinella spiralis, glucan (G test),and galactomannan (GM test) were performed. The results of flexible bronchoscopy showed bronchial casts and endobronchial inflammation (Figure 2A and B), nextgeneration sequencing of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid showed that it was positive forBotrytis cinerea, the serological G test was positive, the serological tests for parasites and the GM test were negative, and histopathology examination revealed an eosinophilic abscess (Figure 2C). Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with plastic bronchitis associated withBotrytis cinereapneumonia, and the subsequent treatment consisted of fluconazole and symptomatic and supportive treatment (detailed below).Following treatment, the patient showed substantial recovery, his cough and expectoration almost disappeared, and he was discharged home.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis of the patient was plastic bronchitis associated withBotrytis cinereapneumonia.

TREATMENT

Initially, we diagnosed the patient with lobar pneumonia and treated him with amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (iv 30 mg/kg once every 8 h). Then, we revised the diagnosis to plastic bronchitis associated withBotrytis cinereapneumonia according to the results of flexible bronchoscopy and next-generation sequencing of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in addition to his increased eosinophils, G test results,and pathological examination results. The patient was given fluconazole (po 6 mg/kg per day, 7 d), and symptomatic and supportive treatment was continued from admission until he was discharged home. After discharge, he continued to take fluconazole orally for a week (po 6 mg/kg per day, 7 d).

Figure 1 Radiological findings. A and B: Chest computed tomography (CT) images showing right upper lobe pneumonia with segmental atelectasis; C and D:Chest CT images showing that the inflammatory lesions of the right upper lung were expanded and new lesions appeared in the right lower lung; E and F: Chest CT images showing that the inflammatory lesions were diminished and the atelectasis was partially restored.

Figure 2 Bronchoscopic and histopathological examination findings. A: Flexible bronchoscopy showed complete obstruction of the right bronchiole by a white and elastic substance; B: A bronchial tree-like plastic dendritic cast was extracted using flexible bronchoscopy; C: Hematoxylin-eosin staining of the bronchial tree-like casts showed extensive eosinophilic infiltration (× 100).

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient was followed for 2 wk. At the time of the writing of this case report, his cough and expectoration had disappeared, his breathing was smooth, his breathing sounds were clear in both lungs, and repeat chest CT results showed that the inflammatory lesions were diminished and the atelectasis was partially restored(Figure 1E and F).

DISCUSSION

Most reports of BC have described it in association with PB. The clinical manifestations of PB are varied, including cough, shortness of breath, wheezing, severe respiratory or circulatory failure, and multiple organ dysfunction[3,10]. Even though CT scan may yield a finger-in-glove pattern or atelectasis, the detection of bronchial dendritic casts by flexible bronchoscopy is the gold standard for the diagnosis of PB. Cases of PB are classified into two types: Type I is caused by inflammatory disease and consists mainly of inflammatory cells and fibrin, while Type II (acellular) occurs only in patients with congenital heart disease and is mainly composed of mucin with little or without infiltration of cells[11]. Histopathological examination of our patient's specimen revealed fibrinoid and necrotic tissue with extensive acute inflammatory cell infiltration, and eventually, a diagnosis of type I PB was rendered. The definitive etiologies of PB are unknown, and most cases have been reported as a complication of congenital heart defect repair in children. New causes of PB have recently been identified, such asMycoplasma pneumoniaeinfection, influenza virus infection,adenovirus infection, asthma, and lung transplantation[2-6]. Interestingly, this patient's complete blood cell count test indicated eosinophilia rather than neutrophilia, and his histopathology examination revealed an eosinophilic abscess. On the basis of the results of the G test and next-generation sequencing of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid and effective fluconazole treatment,Botrytis cinereainfection should be considered.

To the best of our knowledge,Botrytis cinereais considered an endophytic fungus that can colonize the plant and exhibit facultative pathogenic behavior[7]. It was demonstrated thatBotrytis cinereadeploys sRNAs and effector proteins to inhibit the premature death and immune response of host cells, which enables the fungus to establish and accumulate biomass inside the host prior to the necrotrophic phase[12]. A recent study found thatBotrytis cinereacould be detected in the brain tissue of Alzheimer's patients by next-generation sequencing[9], suggesting that it has a potential effect on human health. In our case, this patient had a history of 3 mo of inhaled corticosteroid therapy, which may be a risk factor for infection. In addition, his intradermal allergen test was positive for mycetes, and we hypothesized that in addition to infectious factors,Botrytis cinereamay also induce allergic inflammatory reactions, which can be confirmed by his eosinophil elevation in his complete blood cell count and eosinophilic abscess in histopathology examination. Using flexible bronchoscopy to remove the casts and bronchoalveolar lavage are vital for treating PB[5]. Other treatments for PB have mainly focused on percutaneous thoracic intervention after the Fontan procedure[13]. In our case, the patient received fluconazole antifungal therapy in addition to the removal of the casts. Thus, in our opinion, in addition to timely removal of casts, etiological treatment is the key to improving the prognosis.

CONCLUSION

PB should be considered in children with prolonged cough and atelectasis.Botrytis cinereapneumonia should be considered as a differential diagnosis in children with PB who still have prolonged cough and atelectasis after a regular course of antibiotic therapy. Flexible bronchoscopy should be performed as early as possible to confirm the diagnosis, determine the etiology, remove the obstruction, and target etiological treatment.

杂志排行

World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary heart disease

- Remission of hepatotoxicity in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis patients after lowering trough concentration of voriconazole

- Endoscopic submucosal dissection as alternative to surgery for complicated gastric heterotopic pancreas

- Observation of the effects of three methods for reducing perineal swelling in children with developmental hip dislocation

- Predictive value of serum cystatin C for risk of mortality in severe and critically ill patients with COVID-19

- Sleep quality of patients with postoperative glioma at home