历史性视角下后工业区景观认知及实践变革研究

2020-02-25卢卡玛丽亚弗朗西斯科法布里斯李梦一欣

(意)卢卡·玛丽亚·弗朗西斯科·法布里斯 李梦一欣

0 前言

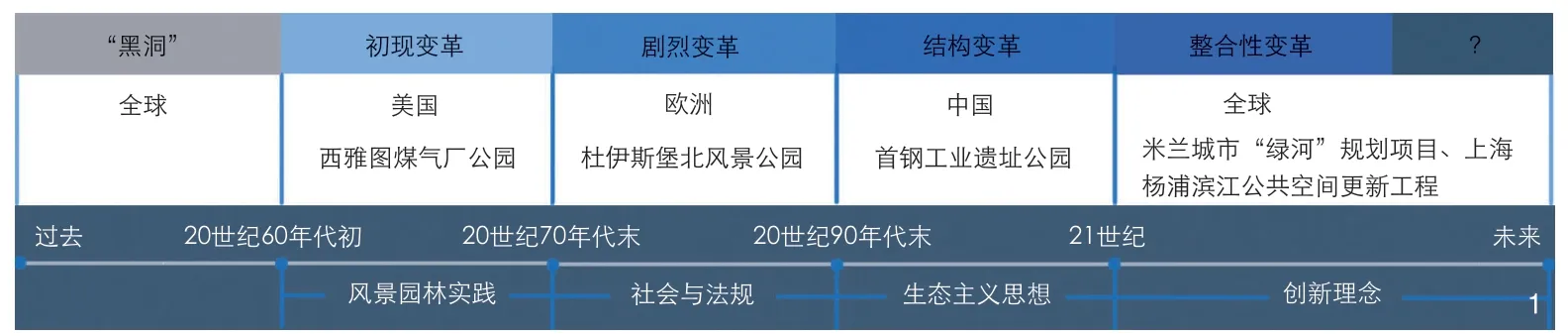

20世纪60年代以前,工业废弃地被视为城市结构中潜藏的“黑洞”。随着工业景观的历史性变革,后工业区已反身成为城市发展和区域环境改善的最大机遇之一。笔者以时间为轴线,剖析全球视野下后工业景观发展的历史脉络和更新过程。在历史与当下互观的研究视角下,对具有划时代意义的研究案例进行切片,映射不同历史分期景观理论与相关设计实践的共轭演变。以史镜鉴,为当下后工业景观理论与实践探索提供依据。

将具有变革性质的后工业景观解读为历史对象,属于一种历时性研究和解释性分析。历史是一种思维方式[1],彼得 拉茨(Peter Latz)[2]提出景观本质上是由多层“信息”叠加累积而成的历史,在时间的流动中“信息密度”演化为历史的厚度。对历史的研究就是拆解“信息”的过程,着重关注历史对象的3个维度:1)不同理念认知下的后工业景观历时性分析;2)对后工业景观变革内涵的挖掘;3)在把握内涵的基础上,对后工业景观里程碑案例进行重新诠释(图1)。

1 以时间为轴线的“历史分期—变革内涵—里程碑案例”研究脉络The “historical phase evolving connotation case milestones” research context in the timeline

1 后工业区景观变革历史分期

纵观后工业景观变革的历史,由初期生态危机引发的工业废弃地与社会、环境问题,发展到生态主义思想、环境治理法规、美学范式转向等因素影响下的后工业区转化与更新,再到创新理念下的工业废弃地与城市、区域综合发展。其关键动力涉及4个方面:1)风景园林设计实践;2)社会与法规;3)生态主义思想;4)创新理念。在此基础上,笔者提出后工业景观变革的4个历史分期:初现变革、剧烈变革、结构变革和整合性变革。整个历程充分揭示了景观变革思想从萌芽到成熟的过程,“景观”已成为解决社会、环境等复杂问题的科学手段之一,而工业废弃地也因此被视为探索后工业景观的试验场,承载着理念、策略的实施与检验。

1.1 第一阶段:初现变革

20世纪60年代初—70年代末,被视为后工业景观变革的开端。由于产业结构转型和工业生产技术创新,美国率先思考陈旧工厂设备的利用问题,初步探索后工业区更新。随着生态主义思想的兴起,特别是受到蕾切尔 卡逊(Rachel Carson)《寂静的春天》(Silent Spring,1962年)的影响,生态主义者对人类行为所造成的严重威胁自身生存的生态环境危机进行了广泛探讨[3]25。然而,处于发展初期的生态主义思想并未对后工业区更新实践产生直接影响。风景园林师开始关注废弃地更新问题,但整体认知相对粗浅,很难预想到对大规模废弃工业设备的保存及永续利用,也几乎没有针对土壤环境修复的详细研究。处理工业废弃地的基本做法是将其纳入待激活的城市肌理,或是直接归入土地吸引力等级较差区域,禁止人们使用。初现变革阶段,理查德 哈格(Richard Haag)的西雅图煤气厂公园(Gas Work Park,1971年)成为独树一帜的项目案例,通过设计实践寻找后工业区更新的发展途径,首次将跨学科知识运用到废弃土地修复中,展现了风景园林师对后工业景观的初步探索。

这一时期体现了后工业景观变革的初阶性特征:1)后工业区更新是产业转型的必然结果;2)生态危机影响下的废弃地更新问题逐渐引起人们的关注,风景园林师对后工业景观的认知处于起步阶段,面对复杂的现实问题,试图通过跨学科的实践手段进行更多的专业性探索。

1.2 第二阶段:剧烈变革

20世纪80年代初—90年代末,后工业区更新发展迅猛,相关理论研究与实践探索遍及整个欧洲大陆。产业工人失业率增加、重工业厂区永久关闭、生态主义运动全面发展等因素共同激发了后工业景观的剧烈变革。社会、生态、法规层面的干预措施相继出现,工业废弃地更新实现了人为干预与生态过程相互协调的变革历程。在后工业区,当人为影响力(管理养护强度)锐减,自然逐渐接管了场地,“工业自然”(“第四类自然”)作为一种新的自然观被提出,它成为后工业景观被感知的原点:一种工业之“荒颓”与自然之“野”的交融在这场变革中得以清晰呈现[4]9。由此,景观美学借由社会变革实现了范式转向,工业废墟美学开始进入人们的视野。

这一时期最具代表性的案例就是令人瞩目的德国国际建筑展埃姆舍公园项目(IBA Emscher Park),通过“批判性重建”解决工业废弃地引发的社会、生态、经济、文化等一系列区域问题[5]。在欧洲范围内,它创造了一系列可转译的项目模式。在政府、非营利组织、民众等多方势力引导下,景观作为重要的空间发展策略促使整个区域系统被重新激活。生态修复、再自然化过程、生态网络、绿色廊道、公共绿色空间系统等成为埃姆舍地区景观更新计划的关键要素[6]。在成熟的生态主义思想影响下,基于自然的解决方案(Natural Based Solutions, NBS)已被应用于多尺度的欧洲环境设计实践。

这一变革时期的特征是:1)基于复杂的社会、环境条件,后工业区更新开始有了跨区域的整体发展策略,形成连贯的绿色空间网络,景观成为激活区域空间发展的手段; 2)区域、城市规划等相关法规的颁布促使后工业景观变革具有了规范性和约束力;3)处于理论化、系统化阶段的生态主义思想深深地影响了后工业区更新的设计和实施手段,促进了景观美学的新发展、环境的再生与生态恢复、绿色空间的更新等。

1.3 第三阶段:结构变革

21世纪初,受到全球后工业景观变革快速化进程的影响,中国成为第三阶段结构性变革的主要代表。20世纪80年代末,中国步入国际工业化市场。科学研究与技术创新引领下的新型机械制造水平大幅提升,工业设备的生命周期(从建造到淘汰的过程)明显缩短,几十年间工业废弃地更新需求明显增加。随着生态可持续原则的应用和生态文明建设纲领的提出,中国已开始实施一系列重大生态举措,将生态文明观作为城市发展的重要政策性内容。相比欧美发达国家的变革历程,中国自上而下的绿色空间政策对后工业区更新产生了前所未有的积极影响。在这一前提下,社会、生态、文化、政治等因素干预下的后工业场地得以重塑。景观也因此成为调整区域空间、修复工业废弃地的结构性工具。其中,北京首钢工业遗址公园成为结构变革中的典型案例。

这一阶段展现了后工业区景观变革的特殊性:1)在生态文明制度体系下,数十项绿色改革措施极大地促进了后工业区更新的规模和速度;2)景观成为后工业区开发、更新的结构性工具;3)自上而下的生态环境保护动力促使工业废弃地成为景观更新的试验场。

2 西雅图煤气厂公园中的后工业遗迹A view of the Gas Work Park with its post-industrial relics

1.4 第四阶段:整合性变革

近年来,随着生态可持续概念的发展,城市韧性、城市新陈代谢等创新理念开始融入风景园林设计之中,这使得全球背景下的后工业景观变革呈现出明显的整合性特征。城市被视作一个复杂且开放的有机体,社会、经济、环境等因素及其相互关系通过物质循环和能量流动与城市系统耦合,形成一个连续的时空动态过程。基于这一视角,城市景观是对自然自生演替系统及城市自主发展过程的表征,具有流动性、异质性、自组织性、隐喻性等特征。这一景观认识论上的转变使得场地潜藏的各种信息、要素及其动态关系不断被纳入后工业景观更新之中,以促进城市、人、自然等关系的和谐健康发展。在国土空间范围内,不同尺度下的后工业区更新视角、维度、内容因而变得更加全面、开放,面向未来呈现出多元发展趋势。其中,米兰城市“绿河”规划项目与上海杨浦滨江公共空间更新工程成为解析后工业景观整合性变革的先锋案例。

历史研究视角下,不同变革阶段显现出工业文化在时空循环和跃迁中的不断发展,揭示了工业废弃地更新在不同文化语境中的内涵演变和影响因素。对于风景园林师来说,必须珍惜每一个重要历史遗存,才能让景观生长的土壤更加肥沃[7]。

2 后工业区景观变革内涵

基于对研究对象的历时性分析,笔者将深入剖析后工业景观变革的4个主要方面:风景园林实践、社会与法规、生态主义思想、创新理念。它们不仅作为不同变革阶段后工业景观发展的驱动因子,而且为解析标志性案例提供了理论依据。

2.1 风景园林实践

自20世纪70年代以来,风景园林逐渐被视为融合各类专业知识(从建筑学到城市规划,从地理学、植物学、生态学到水文学等)的复杂性学科。对风景园林的认知实现了由多学科定义、跨学科发展到交叉学科共融的变化过程。伊恩 麦克哈格(Ian McHarg)的《设计结合自然》(Design with Nature,1969年)是这一系列转变的起点,成为风景园林实践变迁的理论基石。兼顾理论性与可操作性,通过生态设计的思想和适宜性分析的生态规划方法,在现代风景园林设计中开拓了崭新的领域[3]147。

这一内涵体现在初现变革阶段的西雅图煤气厂公园案例中(图2),不仅通过真实的项目实践方式推动后工业景观理论的发展,而且成为后工业景观跨学科协作的开端。由此,当代风景园林实践不再局限于自然、如画的造景方式,而是面对复杂的现实世界,运用多学科知识,创造自然、人类技术与人工制品(及其生命周期)共生的真实环境[8]。

2.2 社会与法规

1)社会层面。田园美学的发展阐释了人类、技术与工业化之间的矛盾,持续的去工业化过程引发了风景园林师对新的工业废墟美学的专业性探讨,以及对自然、技术和景观三者关系的重构。在景观美学转向的背景下,人们开始批判性地思考工业废弃地、生态修复、日常生活介入和城市野境美学之间的系统性关系。

2)法规层面。根据联合国报告《我们共同的未来》(Our Common Future,1987年)所提出的生态可持续理念,在剧烈变革阶段欧洲各国相继颁布多项法规以促进后工业区的发展与更新,主要涉及区域和城市规划、可持续建筑、景观规划和生态等方面。其中,《欧洲风景公约》(European Landscape Convention, 2000年)在环境治理层面对后工业景观变革和欧洲绿色空间设计产生了深远影响。这一具有规范性和指导作用的法规提出景观须“按原貌”呈现新理念,表明欧洲文化语境下的景观内涵是对人的行为活动和具体政策的反映与表达[9]。这一定义颠覆了以传统美学为导向的景观认知,将错综复杂的社会、文化等因素融入后工业景观设计之中。

2.3 生态主义思想

在结构变革阶段,随着中国生态文明建设的不断推进,尊重自然、顺应自然、保护自然的生态文明理念已作为伦理生态构建的重要内容。从战略高度,中国在政策与制度层面重申了景观的美学、生态、环境、文化以及伦理价值内涵,使景观作为“美丽中国”的空间载体和系统解决城市生态环境的综合途径[10],明确生态主义思想是空间规划发展的科学工具。强有力的制度保障在很大程度上超越了欧美生态主义思想从初步发展、全面成熟到多元化、系统化的一般发展过程。在借鉴西方发达国家过去30年实践经验的基础上,中国后工业区更新初步具备了赶超欧洲设计模式的发展潜力,开始出现一些高质量的风景园林设计作品。

2.4 创新理念

在整合性变革阶段,全球工业废弃地更新成为人类共同面临的任务与挑战,而摆脱千篇一律的城市景观模式是这一进程中的关键问题。对此,各国风景园林师须深刻理解韧性城市、健康城市等创新理念,通过风景园林设计积极将城市作为开放、复杂的生命有机体,利用不同学科知识和各种环境设计要素激活工业废弃地,并视具体情况制定和调整景观解决方案[11]。同时,探索不同文化语境下多元的后工业景观的地域性表达,使城市空间具备抵抗灾害冲击、有序恢复和提质增效的适应能力。在此基础上,创造更多具有实验性、探索性的实践项目,激发新的区域文化景观特征。事实上,这一过程很有可能成为未来后工业景观持续变革的新方向。

3 里程碑案例

3 20世纪70年代初西雅图煤气厂公园的生物修复工程The bioremediation works at Gas Work Park in the early 1970s

4 德国杜伊斯堡北风景公园中的“工业自然”之美The beauty of “industrial nature” in Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park

5 斯蒂法诺 博埃里建筑事务所提出的米兰“绿河”计划Milan “Green River” Plan proposal by Stefano Boeri Associati

历经50年的后工业景观变革涌现了许多优秀的风景园林设计案例。基于对历史分期和变革内涵的研究,一系列里程碑案例被重新诠释,它们分别是:理查德 哈格及其合伙人(Richard Haag Associates)设计的美国西雅图煤气厂公园(1971年)、彼得 拉茨设计的德国杜伊斯堡北风景公园(1995年)、北京首钢工业遗址公园(2016年)、斯蒂法诺 博埃里建筑事务所(Stefano Boeri Associati)设计的米兰城市“绿河”规划项目(2018年),以及上海杨浦滨江公共空间更新工程(2018年)。这些世界范围内极具影响力的后工业景观案例作为风景园林理论与实践相融的典范,揭示了后工业区历时性变革中的关键因素。

3.1 西雅图煤气厂公园

西雅图煤气厂公园是后工业景观初现变革阶段的首枚案例,标志着世界范围内“工业废弃地转向城市公园”成为一种明确的景观模式。以跨学科实践为导向,设计师理查德 哈格首次聚集了不同学科的专业技术人员。在与化学工程师理查德 布鲁克斯(Richard Brooks)的合作中,他们发现了地表除污方法,即通过翻耕锯末、灌溉污水淤泥和其他有机物来激活本土微生物(图3),利用非常规技术手段解决了工业废弃地的土壤污染问题。作为首次尝试生物修复技术的后工业景观案例,它证明了受污染土地可以在较短时间内得到修复和再生。总之,这一项目揭示了后工业景观探索初期,一个勇敢的研究者在该领域所付出努力的最显著成果。自此,跨学科的协作方式被普遍应用,例如麦克格雷戈及其合伙人(McGregor + Partner)设计的悉尼英国石油公司遗址公园(BP Park in Sydney,2006年)[12]。

3.2 杜伊斯堡北风景公园

彼得 拉茨的杜伊斯堡北风景公园是后工业景观剧烈变革阶段的代表性案例,体现了景观变革在社会、法规层面的发展。

1)遵循场地历史轨迹,整个后工业区被一种野性的、反叛性的绿色所占据。由埃姆舍公园项目策展人提出的“工业自然”概念在杜伊斯堡北风景公园中得以实施,“工业自然”是将人们对城市自然的感知与荒野美学建立联系[13-14](图4),是一种无法用传统园林美学来包容的气质[4]9。德国风景园林不再致力于强调自然完美无瑕的美学特征,而是在后工业区阐释社会审美价值的转变,出现了一种将工业遗存的崇高性与自然过程并置的风景园林设计手段。

2)遵循德国《联邦自然保护法》(BNatSchG,1976年),“景观”应具备“美学性、特殊性、多样性和稀有性”特征[15]。在杜伊斯堡北风景公园中,通过风景园林师的“思想、内心、双手”三位一体地呈现出来,反映了对复杂人造场地的分析和结构化处理,展现了设计师对场地修复和再生的热情,对物质世界的塑造和构形[16]。这一法案还明确了“景观规划”作为一种跨区域的空间发展工具,旨在强调自然在城市环境中的意义和价值,通过自上而下的规划措施提升德国城市生态环境质量。而杜伊斯堡北风景公园成为区域尺度下实施景观规划方法与自然可持续发展原则的探索性案例。

3.3 首钢工业遗址公园

首先,在结构性变革中,首钢工业遗址公园充分体现了景观成为调整区域结构、整合绿色空间资源、修复工业废弃地的结构性工具。在北京市的总体规划中,首钢工业遗址公园位于长安街沿线的东西轴与西部绿色生态发展带交汇处,是构建首都核心功能区绿色空间的重要组成部分,将呈现出工业遗迹与绿色自然风貌交融的整体景观特征。通过整合首钢地区所依傍的永定河、石景山、三山五园等丰富的山水资源,构建以南北山水轴线为统领的首都山水文化生态公园,在区域尺度上完善北京城市公园绿色空间 网络[17]。

其次,该项目是自上而下生态主义思想指导下的城市再生与修复项目。在前期规划中,北京市城市规划研究院和首钢集团共同制定了全面的低碳城市发展与生态规划,使其成为中国第一个“C40正气候发展项目”,旨在证明城市能以气候友好和减少碳排放的方式发展[18]。在生态可持续发展理念下,绿色建筑、清洁能源、废弃物管理、水资源、绿色空间、工业遗址等要素成为首钢工业废弃地更新的重要手段。

3.4 米兰与上海的案例

在全球整合性变革中,韧性城市、健康城市等创新理念推动着后工业景观的多元化探索。其中,米兰城市“绿河”规划项目和上海杨浦滨江公共空间更新工程是城市面向未来可持续发展的先锋案例。

在米兰城市管理部门与意大利铁路局的共同开发下,新的绿色系统规划项目预计于2020年投入实施。这一系统被隐喻为城市的“绿河”,由斯蒂法诺 博埃里建筑事务所规划设计(图5)。项目通过环形绿廊连接米兰的7个城市火车站,整合了区域内大部分已转变为城市公园的后工业区,以实现空间一体化构思。大量被废弃的铁路货运场也被“绿河”连接,旨在创造联通城郊空间的新型绿色基础设施(图6)。“绿河”概念表明不同尺度下绿色空间措施的重要性,如同英国伦敦绿带或德国慕尼黑绿廊对城市空间发展产生的综合效应。基于城市历史肌理,这一空间再生项目创造了一种新的动态发展网络,通过土地“留白”而非占用的方式完善城市空间结构,提升城市韧性。其创新之处在于启动了一种缓慢且持续的城市景观更新方式,将对伦巴第大区(Lombard)城市未来空间诠释方式产生积极影响。总之,项目证明了城市作为生命有机体,在面向未来的开放区域中,景观将以自然为底成为空间记忆与区域变革的重要载体。

6 法里尼铁路货运场空间更新The spatial renewal of former Farini Railway-Yard

7 上海黄浦江西岸景观设计Western riverside landscape of Huangpu River in Shanghai

8 作为历史纪念物的工业遗产赋予景观设计新的特征The industrial heritage as historical monument giving a new character to the landscape design

在上海杨浦滨江公共空间更新工程中,后工业景观被视为城市、自然、人、工业遗存和各种环境设计要素相互交织、流动的有机界面。人们不再通过增加数百万立方米的城市构筑物来“征服”这条历史性河流,而是利用风景园林设计和多种生态技术手段开发一系列后工业场地。通过景观的软性介入,连接黄浦江右岸北部与南部①的新、旧基础设施 (图7)。人们在强有力的工业构筑物上嫁接出可永续利用的城市景观内容(图8);与此同时,以人为本的、丰富的绿色开放空间逐渐被赋予新的城市日常使用功能,后工业景观成为未来可持续发展的重要基础。

4 结语

通过历史分期—变革内涵—里程碑案例这一研究脉络,后工业景观历史性变革得以清晰呈现。以时间为轴线,潜藏在后工业区更新中的社会、文化、生态、政策、空间等各种信息被人们拆解、拼接、复合,一幅幅生动的景观图像在时空中叠加、交错、变化。景观成为这场变革的基础,也是后工业区复兴的关键。

后工业区景观变革从美国跨越欧洲,发展到中国,最终扩展到全球范围。这一过程揭示了地理空间转化下不同变革主体对后工业区更新的多样化探索。事实上,4个历史分期的内容并不具有明显的前后继承性,笔者认为它们只是这一复杂演变过程中亟待被抽离的重要历史切片,是在提取多层信息的基础上对不同变革阶段所进行的逻辑分析,旨在剖析不同动因下的后工业区更新:景观设计实践下的初现变革、社会与法规引导下的剧烈变革、生态主义思想统领下的结构变革、创新理念激发下的整合性变革。

在此基础上,本研究试图对当下中国后工业景观发展提供一些思路。1)设计实践是检验后工业景观理论的途径,也是中国借鉴国际成功经验、创造更多标志性案例的主要方式,更是展现文化自信与地域景观特征的最佳机遇。2)在社会和法规层面,尽管理论研究视角下的西方工业废墟美学已被大多数风景园林师所认知,但仍须对具有中国特色的“工业自然”概念进行分析与凝练,社会层面的审美转向也亟待发生。在法规层面,中国须制定、发展更多与后工业区更新密切相关的法律和政策,使工业废弃地设计与建造更具规范性。3)在中国生态文明建设中,自上而下的生态主义思想具有明显的制度优势,风景园林师须更多地关注、发现其本质内涵,借助后工业区更新这一契机,为“美丽中国”建设做出贡献。4)面向未来的后工业区更新需要具有包容性、整合性的创新思维:不同学科、多种环境设计要素都可以为废弃地改造提供开放、多元的处理方式,其关键在于以景观为手段发展地域化的具体解决方案。

注释:

① 黄浦江右岸北部由设计师张斌、Atelier z+负责监督和开发;黄浦江右岸南部由设计师章明策划。

图片来源:

图1由作者绘制;图2、4、7~8由作者提供;图3由RHA提供;图5~6由斯蒂法诺 博埃里建筑事务所提供。

(编辑/王亚莺)

Research on Post-industrial Area Landscape Cognition and Practice Transformation from a Historical Perspective0 Preamble

(ITA) Luca Maria Francesco Fabris, LI Mengyixin*

Before the 1960s, abandoned post-industrial areas were considered as black holes inside the urban fabric. With the historic transformation of industrial landscapes, they have turned into one of the greatest opportunities for urban development and regional environmental improvement. The article takes time as the axis to analyze the historical context and renewal process of post-industrial landscape development from a global perspective. From the perspective of the mutual view of history and present, the study discusses epoch-making cases, aiming to reflect the conjugate evolution of landscape theories and related design practices in different historical phases. Taking history as a mirror, the study provides the basis for the current post-industrial landscape explorations of theories and practices.

The article interprets the post-industrial landscape transformation as a historical object, which belongs to a kind of diachronic research and explanatory analysis. History is a way of thinking[1]. Peter Latz proposed that the landscape is basically the history of multiple layers of “information” superimposed and accumulated. In the flow of time, this “information density” evolves into the thickness of history[2]. The study of history is the process of disassembling “information”. The authors focus on three dimensions of historical objects: 1) Diachronic analysis of post-industrial landscapes under different cognitive concepts; 2) Digging into the connotations of post-industrial landscape transformation; 3) On the basis of grasping the connotations, re-interpreting some milestone case studies of post-industrial landscape design (Fig. 1).1 Historical Phases of Post-industrial Landscape Transformation

Through the history of post-industrial landscape transformation, the industrial wasteland, social, and environmental problems caused by the early ecological crisis have developed into the renewal of post-industrial areas under the comprehensive influence of ecological ideas, environmental legislations, an aesthetic paradigm shift, and then the innovative concepts. Among which, the key driving forces involve four aspect: 1) Landscape design practice; 2) Society and legislations; 3) Ecological thoughts; 4) Innovative ideas. On this basis, the authors propose four historical phases: soft, strong, structural, and merging post-industrial landscape transformations. The whole process fully reveals the landscape transformation evolving from embryo to maturity. Landscape has become one of the scientific means to solve complex social and environmental problems, and we can consider abandoned industrial areas as experimental laboratories where different strategies have been tested over time.

1.1 The First Phase: Soft Transformation

From the early 1960s to the late 1970s, it was regarded as the beginning of the postindustrial landscape transformation. Due to the transformation of industrial structure and the implementation of new production technologies, the USA took the lead in thinking about the utilization of obsolete industrial equipment and initially explored the renewal of industrial areas. With the rise of ecological thought, especially under the influence of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962), first ecologists have carried out extensive discussions of an ecological and environmental crisis that seriously threatens the whole biosphere survival compromised by human behaviors[3]25. However, the ecological ideas at the early stage did not have a direct impact on the post-industrial area renewal practice. Landscape architects began to pay attention to the problem of derelict area renewal, but the overall understanding is relatively shallow. They did not foresee the maintenance of the original artefacts for other use nor the reclamation and requalification of the soils, but directly the reintegration into the urban fabric of these areas such as portions to be reactivated through market laws or to be delimited and prohibited in the event of poor land attractiveness. In this first phase, Richard Haag's Seattle Gas Works Park (1971) is a unique project. Through the design practice, the development path of the post-industrial areas were renewed, and the interdisciplinary knowledge was applied to the decontamination and restoration of the abandoned land for the first time, showing the landscape architects' preliminary explorations of post-industrial landscapes.

This stage embodies the initial characteristics of post-industrial landscape transformation: 1) The post-industrial areas renewal is an inevitable result of industrial change; 2) Under the influence of ecological crisis, the problem of abandoned land renewal gradually aroused professionals' attention. Landscape architects had a tentative understanding of post-industrial landscape and facing complex practical problems, they tried to explore the post-industrial areas renewal through interdisciplinary means.

1.2 The Second Phase: Strong Transformation

From the early 1980s to the late 1990s, the postindustrial areas have been developing rapidly, and the related theoretical research and practical explorations have spread throughout the European continent. The coexistence of the end of work tragedy, with the closure of many heavy industrial plants, combined with the birth of the ecological movement, has stimulated drastic changes in the post-industrial landscapes. Intervention measures at the social, ecological and legislative levels have emerged. The renewal of industrial wastelands has achieved a coordinated transformation between human intervention and ecological processes. In the postindustrial areas, the sharp decline in human influence (management intensity) lead to nature taking over the site step by step. This brought to the concept of “industrial nature” (“the fourth nature”) proposed as a new view of nature, which become the origin describing the complete post-industrial landscape as perceived. The strong transformation presents clearly the blending of the “decadence” of artificial work (the industry ) and the “wild” of nature[4]9. As a result, the paradigm shift of landscape aesthetics from social and legislative changes has led to the industrial ruin aesthetics beginning to enter people's horizons.

The most representative case of this period is the remarkable German IBA Emscher Park, which through “critical reconstruction” solved the social, ecological, economic, cultural, and other regional problems caused by derelict areas[5]. Under the guidance of government, non-profit organizations, local people and other multi-party forces, landscape architecture immediately revealed itself as the element capable of constituting the solid foundation on which to articulate the whole system of activities able of reactivating the territory. Remediation, re-naturalization, ecological networks, green corridors, and nets of public green spaces were among the key elements of the IBA Emscher Park program[6], that we will then find in the following German IBAs and in other similar programs throughout Europe, where, it is useful to remember, the practices related to NBS (Natural Based Solutions) have become common practices of environmental design at all scales.

The characteristics of this period are: 1) Based on complex social and environmental conditions, the post-industrial area renewal began to implement a cross-regional overall development strategy, shaping a coherent green space network, and the landscape became the structural basis for reactivating regional spatial development; 2) The relevant regional and urban planning legislations have promoted the postindustrial landscape transformation to be normative and binding; 3) The ecological thought during the theoretical and systematic stage has profoundly influenced the design and implementation of post-industrial area renewal, and has promoted the new development of landscape aesthetics, the regeneration of environmental restoration, and the green space renewal.

1.3 The Third Phases: Structural Transformation

After the start of the second millennium, we must go to China to witness the third step of this revolution, which we can define as “structural”. As we all know, China has entered the international industrial market since the late 1980s and did so with an impetus that accelerated and condensed what happened in decades in other parts of the world in a handful of years. From construction to their obsolescence, industrial plants have a life cycle that has been reduced from various decades into a bunch of years and scientific research and technological innovation often led to the construction of new plants, even before dismantling or renovating the existing ones. But, on the wave of the increasing importance of the principles of ecology and sustainability, and with the launch of ecological awareness policies, in the great Asian country, a whole series of principles have been implemented allowing planners to reshape the industry and redesign the territory through multi-scalar interventions that have better recovered the models previously defined in Europe. Landscape architecture becomes the tool through which structural and recovery modifications can be made in cities and their compromised sectors. Among them, Beijing Shougang Industrial Park is a typical case in this structural transformation.

This period shows the particularity of the postindustrial landscape transformation: 1) Under the ecological civilization system, green space policies have promoted the scale and the speed of postindustrial area renewal; 2) The “landscape” has become a structural tool for the development and renewal of post-industrial areas; 3) The top-down driving forces of ecological and environmental protection promote the derelict areas as a laboratory for post-industrial landscape renewal.1.4 The Forth Phases: Merging Transformation

In recent years, as the innovative concepts of urban resilience and metabolism which evolved under the notion of sustainability integrated into landscape design, the post-industrial landscape transformation in the global context has shown merging characteristics. Our metropolis is interpreted as an open and complex organism always struggling to reach a perfect equilibrium that brings advantages not only to human inhabitants but to all the components that create a city. The social, economic, environmental and other factors as well as their interrelationships are coupled with the urban system through material circulation and energy flow to form a continuous spatiotemporal dynamic process. Based on this perspective, the urban landscape is a representation of the natural spontaneous succession system and urban autonomous development process, and has the characteristics of mobility, heterogeneity, self-organization, and metaphor. At the territorial and urban levels, perspectives, dimensions and contents of the postindustrial areas renewal are more comprehensive and open, presenting a diversified development trend toward the future. Among them, two different examples from two metropolitan cities (Milan and Shanghai) describe well what is now the state-of-theart produced by this global trend of transformation based on merging all the diverse subjects having as common element the relation with Nature.

From the perspective of historical research, the different stages show the continuous development of industrial culture in the spatiotemporal cycle and transition, revealing the connotation evolution and main influencing factors of industrial areas renewal in various cultural contexts. For landscape architects, every important historical relics must be cherished in order to make the soil for landscape growth more fertile[7].

2 The Connotations of Post-industrial Landscape Transformation

Based on the diachronic analysis of the research object, the authors will deeply explore different but inter-connected levels of the postindustrial landscape transformation in parallel with the four phases described in the previous chapter of this article: landscape design practice, society and legislation, and ecological and innovative ideas. These aspects not only serve as driving factors for the development of industrial landscapes in various stages, but also provide the theoretical basis for the analysis of case milestones.

2.1 Landscape Design Practice Level

Since the 1970s, landscape architecture has always been a complex subject combining different kinds of knowledge (from architecture to planning, from geography, botanical, ecology to hydrology and so on). This subject, born “multidisciplinary” by definition, evolved into interdisciplinary and then into a transdisciplinary dimension. The bookDesign with Natureby Ian McHarg (1969) was the starting point of this change and has become an important cornerstone of the changes in landscape theory and ecological planning practice[3]147, which opens up a new field in modern landscape design through the idea of ecological design and planning method of ecological suitability analysis.

This connotation is reflected in the case of one of the first examples, as the Gas Works Park in Seattle by Richard Haag during the phase of soft transformation (Fig. 2). This project innovated the professional practice and applied novel theoryby-doing methods, and becomes the beginning of interdisciplinary collaboration of post-industrial landscape. From then on scholars debating about contemporary landscape couldn't simply refer to mere a natural and pastoral approach, but had to face the interweaved interactions of the contemporary world where nature and human technologies and artefacts (and their cycle of life) coexisting have created a real world[8].

2.2 Social and Legislation Levels

1)At the social level, if we can agree that the development of the pastoral aesthetic expressed our conflicted relationship to technology and industrialization at a particular moment in history, the still on-going process of deindustrialization is provoking other discussions about the new landscape aesthetic emerging from industrial ruins, and the reimagining of our relationship to nature, technology, and landscape. In the context of aesthetical paradigm shift, these critical questions are essentially rethinking the systematic links between post-industrial sites and ecological environment restoration, daily life intervention, and urban wildness aesthetics.

2)At the level of legislation, according to the ecological sustainability concept put forward by the UN report “Our Common Future” (1987), European countries have promulgated a number of laws to promote the development and renewal of post-industrial areas during the stage of strong transformation. The laws included regional and urban planning, landscape planning, sustainable architecture, and ecology. Among which, theEuropean Landscape Convention(2000) has a profound impact on the post-industrial landscape transformation and European green open space design at the level of environmental governance. This normative and guiding legislation proposed that the novel concept of landscape “as it is”, with the meaning that people are living inside the landscape and landscape is a reflection of human activities and policies in the context of European culture[9]. This definition subverts the traditional aesthetic-oriented landscape understanding, and integrating intricate social and cultural factors into the post-industrial landscape design.

2.3 Ecological Level

In the stage of structural transformation, with the continuous advancement of China's ecological civilization construction, the ecological ideas of respecting, conforming to and protecting nature have become an important part of ethical ecology construction. From a strategic perspective, China has reaffirmed the aesthetic, ecological, environmental and ethical values of landscape at the institutional and political levels, making the landscape as a spatial carrier of “Beautiful China” and a comprehensive way to systematically solve the urban ecological environment[10]. A series of powerful institutional guarantees for the construction of ecological civilization have largely surpassed the general process of European and American ecological ideas from initial, comprehensive development to diversification and systematization. Successfully borrowing from the practical experiences of landscape design in western developed countries in the past 30 years, China's post-industrial area renewal has initially had the potential to catch up with the European design models, showing some high-quality post-industrial landscape design projects.

2.4 Innovation Level

In the stage of integrated transformation, the worldwide industrial wasteland renewal has become the common task and challenge faced by mankind. More than ever in the past, we all are now living in a global context where despite of borders, worldwide nations are experiencing situations that are more or less the same everywhere. Getting rid of the stereotyped urban landscape model is also a key issue in this process. In this regard, landscape architects from various countries need to have a deep understanding of innovative concepts such as resilient and healthy cities, that is, actively responding to cities as open and complex living organisms by landscape designs, using different discipline knowledge and various environmental design elements to active industrial wasteland, and formulating landscape solutions according to specific conditions[11]. In the meanwhile, it is necessary to explore the diverse regional expressions of post-industrial landscapes in different cultural contexts, so that urban spaces have the ability to resist disasters, orderly recovery, and improve spatial quality and efficiency. On this basis, more experimental and exploratory projects are created for inspiring new regional cultural landscape features. And this process is likely to become a new direction for the continuous transformation of postindustrial landscapes in the future.3 Cases-Study Milestones

Some representative landscape design projects well witness the post-industrial landscape transformation phases during this 50-year period. Based on the study of historical stages and the changing connotations, a series of case milestones need to be re-interpreted: the Gas Works Park in Seattle (USA) by Richard Haag Associates (1971); the Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park in Duisburg (Germany) by Peter Latz (1995); the Shougang Industrial Heritage Park in Beijing (China, 2016); and the Green River Project in Milan by Stefano Boeri Associati (2018) and the Recovery of Huangpu Riverside Public Space Development Project in Shanghai (2018). These highly influential projects have become and are prototypes models of the integration into landscape architecture theory and practice, revealing the key factors in the diachronic transformation of post-industrial areas.

3.1 Gas Works Park

The Gas Work Park in Seattle is considered as one of the first cases in the soft transformation of post-industrial landscape, which represents the prototype of former industrial areas reconverted as urban park. Guided by the interdisciplinary practice, Richard Haag gathered various professionals who brought together a series of different professional skills in order to verify unconventional techniques for solving the soil-pollution problem. Working together with the chemical engineer Richard Brooks, Haag came up with the solution of removing the contaminants from the surface by activating the indigenous bacteria by tilling sawdust, sewage sludge and other organic compounds (Fig. 3). As one the first examples of bio-remediation, this process proved that, in a relatively short time, contaminated areas could be safely reclaimed. In a word, this project reveals the fruit of the efforts made by a courageous researcher in the field during the early stage of postindustrial landscape exploration. Since then, direct descendants of the approach of interdisciplinary collaboration adopted here can be seen, for example, in the BP Park in Sydney by McGregor + Partner[12].

3.2 Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park

Peter Latz's Duisburg-Nord landscape park is a representative case of the strong transformation phase of post-industrial landscape, reflecting the development of landscape connotation changes at the social and legislation levels.

1)Following the historical trajectory of the site, the entire post-industrial area was occupied by wild and rebellious greenery. The notion of “Industrial Nature” proposed by the German IBA Emscher Park curators was implemented in the Duisburg-Nord landscape park. Industrial nature associates people's perception of urban nature with the wilderness aesthetics of post-industrial areas[13-14], and is considered as a temperament which could not be expressed through traditional garden aesthetics[4]9(Fig. 4). Landscape architecture was not more devoted to finding and highlighting the aesthetic beauty of the perfection of nature, but describes a shift in aesthetic judgment. The landscape design method juxtaposing the sublime of industrial heritage with natural processes has emerged.

2)According to theGerman BNatSchG(1976), “landscape” should have the characteristics of “aesthetic, particularity, diversity, and rarity”[15]. In the Duisburg-Nord Landscape Park, they are presented through the triple actions of “head, heart, hands”, with the head representing the analyzing, the structuring; through the heart, the passion, the human intensity of recovery and regeneration are demonstrated, through the hands the forming, the shaping the material[16]. In the meanwhile, this law also specifies “landscape planning” as a crossregional spatial development tool, which aims to emphasize the significance and value of nature in the urban environment, and improve the quality of German urban ecological conditions through top-down planning measures. This project has become an exploratory case for implementing landscape planning methods and natural sustainable development principles at the regional scale.

3.3 Shougang Industrial Park

In the structural transformation, the Shougang Industrial Park fully embodies how landscape has become a structural tool for adjusting regional structure, integrating green space resources, and restoring industrial wasteland. In Beijing's master plan, this project is located at the intersection of Chang'an Street and the east-west axis along the line, and the western green ecological development zone. It is an important part of building green spaces in the core functional area of the capital and will show the integrated landscape features of both industrial heritage and nature. By combing the abundant natural mountain-water resources such as the Yongding River, Shijingshan, and the Sanshanwuyuan, the Shougang area is rebuilt to be a landscape ecological park according to the north-south landscape axis for improving the green space network of Beijing urban parks at the regional level[17].

The Shougang Industrial Park became an urban regeneration and restoration project under the guidance of top-down ecological ideas. In the preliminary planning, the Beijing Municipal Institute of City Planning and Design and the Shougang Group jointly formulated a comprehensive lowcarbon urban development and ecological plan, making it as the first “C40 positive climate development project” in China. Under the concept of ecological sustainable development, it aims to prove that cities could develop in a climatefriendly manner and reduce carbon emissions[18]. Elements such as green buildings, clean energy, waste management, water resources, green space, and industrial sites have become important means of renovating industrial derelict areas.

3.4 Milan and Shanghai Cases

In the integrated transformation, innovative concepts such as resilient and healthy cities are driving the diversified explorations of postindustrial landscapes. Among them, the Planned New Green System of Milan in Italy and the the Huangpu Riverside Public Space Renewal Project in Shanghai are pioneer cases of the urban sustainable development in the future.

In Milan, the City Administration has developed together with the society that owns the Italian Railways System a project to be implemented by parts starting from 2020, the so-called Green River, designed by Stefano Boeri Associati (Fig. 5). The transformation projects starts from the divestment of 7 city railway stations and designs their interconnection through a circular green corridor that will integrate in the same network most of the industrial brownfields already recovered as public parks in in Milan. The former and unused railway-yards present in the Italian metropolis will be linked to create a new green infrastructure connecting the downtown with the city outskirts (Fig. 6). The Green River of Milan, although not innovative in itself — reader can remember the Green Belt of London or the Green Corridors of Munich as previous examples — is relevant because, for the first time in Europe, this kind of urban regeneration project has its roots in the de-growth and the de-colonization of a historical city fabric. The new green interconnection will be a real infrastructural network that will enrich the town through its emptiness and not through the occupation of land. Here lies the innovation of this project that wants to start a slow but continuous transformation of the urban landscape, which will have consequences both on urban planning and transport and on the way of interpreting the Lombard city and its future. The landscape becomes a place of memory and a place of transformation. In one word, Milan demonstrates that it is a resilient biotope and for this reason promotes a wide territorial program based on the interdisciplinary interconnections of knowledge and on a timeline ruled by nature.

In Huangpu Riverside Public Space Renewal Project, the post-industrial landscape is regarded as an interface where the city, nature, people, industrial heritage and various environmental design elements could interweave and flow. The refurbishment and the revitalization of the Huangpu riversides are not taking place through the imposition of millions of new cubic meters of buildings, but through the techniques of recovering and landscape architecture transformation of many abandoned formerindustrial areas. The northern part and the southern part of the Huangpu right riverside bank (Fig. 7), for example, are infrastructural elements that connect the new with the ancient, maintained as landmark key-points, through the lightness of the landscape (Fig. 8). The outcome is a series of human-scale places intended for collective leisure, but that has also a clear function and is useful. Open spaces that are fundamental elements on which to graft the new parts of the city still in evolution.

4 Conclusions

Through the research logic of historical phases — evolving connotations — case milestones, the historical transformation of post-industrial landscapes could be presented clearly. In the timeline, various information in terms of society, culture, ecology, policy, and space hidden in the post-industrial areas are dismantled, joint, and compounded, and the vivid landscape images are superimposed, interlaced and changed in the time and space. Landscape becomes the basis of changing as well as the key to the revitalization of post-industrial areas.

The post-industrial landscape transformation spanned from the United States to Europe, developed into China, and eventually expanded to the global scale. This process reveals the diversified explorations of post-industrial area renewal by different subjects under the changing of geographic space. As a matter of fact, the contents of the four historical stages do not have obvious inheritance before and after. The authors believe that these analyzed contents are only important historical slices which need to be extracted in the complex evolving process. Their logical analyses are based on the extraction of multiple layers of information for different phases, which aims to present the post-industrial area renewal under different causes: the soft transformation in the landscape design practice, the strong transformation under the guidance of society and legislations, the structural transformation under the leadership of ecological awareness, and the integrated transformation inspired by innovative ideas.

Based on these, the study attempts to provide some ideas for the current development of postindustrial landscapes in China: 1) The landscape design practice is a way to test post-industrial landscape theories, as well as for China to draw successful experiences from international practices to generate more iconic cases. And it is also the best opportunity to show cultural self-confidence and form regional landscape characteristics. 2) At the social and legislation levels, the western aesthetics of industrial ruins from the perspective of theoretical research has been recognized by most landscape architects. However, the concept of Industrial Nature with Chinese characteristics still needs to be analyzed and condensed. The aesthetic turn at the social level is also expected to be happened urgently in China. At the level of legislation, China needs to formulate and develop more laws and policies which are closed related to the renewal of post-industrial areas to make the design and construction of derelict areas more standardized. 3) In the construction of Chinese ecological civilization, top-down ecological ideas have obvious system advantages, to whom landscape architects should pay more attention to and discover the essential ecological connotations. The post-industrial area renewal as a good opportunity will contribute to the construction of “Beautiful China”. 4) The post-industrial landscape changing for the future requires an inclusive and integrated innovative thinking: different disciplines and multiple environmental design elements could provide an open and diversified treatment method for the derelict area transformation. The key lies in the use of landscape as a means to develop specific solutions for regionalism.

Notes:

① The modern art of the Huangpu right riverside bank is developed under the supervision of Zhang Bin and Atelier z+; the southern part of Huangpu right riverside bank is curated by Zhang Ming.

Sources of Figures:

Fig. 1-2, 4, 7-8 © the authors; Fig. 3 © RHA; Fig. 5-6 © Stefano Boeri Associati.