在原生态的村里,遥想当年

2020-02-14郭闻

郭闻

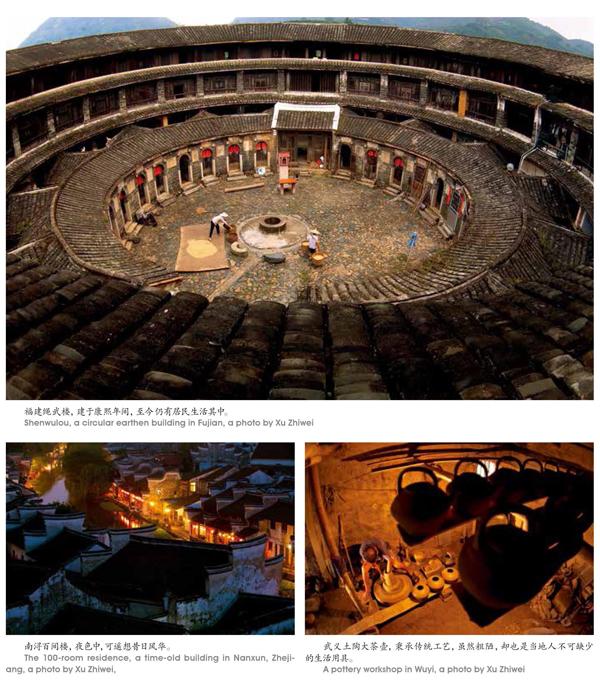

半年来,从他的微信里可以看到,他正自由地奔跑在中国的大地上,去敦煌拍莫高窟,去山西五台山拍寺庙,去福建拍土楼……认识中国文化,认识传统乡村,认识我们的乡愁,认识我们的来处与去向。

中国有句古话,叫“四十不惑”。许志伟,这个40岁出头的杭州男人,在这个年纪找到了自己余生的方向,毅然辞去很多人眼中的“金饭碗”,用相机记录中国的传统文化。

前20年从警,守护世间平安;以后的日子,他想用自己的力量守护中国的文化传承。

(一)

许志伟是个狠人,做事、做人都很认真的狠人。

有一年,七月的烈日暴晒下,准噶尔盆地地表温度突破50摄氏度,空气都因高温而隐隐扭曲、模糊。一个男人背着几乎遮住整个背的摄影包,往远处的一个土坡走去……

我知道,这一场景会成为我一辈子的回忆,不会遗忘。

15年前,我和许志伟一起去新疆采访,路过准噶尔盆地卡拉麦里保护区的时候,他看见路边一土坡上有许多小洞,洞口隐隐出没着旱獭的小脑袋。素来喜爱动物摄影的他立刻要求停车去拍摄。

7月的戈壁荒漠,烈日炙烤,一览无余,在露天喘口气都会觉得嘴里的水分在飞速地蒸发。

我说:“不如你摇下车窗用长焦拍吧,外面太热了。”

他想了想说:“我还是下去拍吧,你在车里等我。”

于是,我躲在開着空调的车里,啃着西瓜,隔着窗呆呆地看着他远去。等到他再回到车上的时候,整个人已经晒成了红壳虾,撤下包,背上的衣服已浸透汗水。一坐下来一瓶水就全喝完了。吐出口气,他郁闷地说:“没拍到,看我走近,这些小东西全钻进洞里了。”

(二)

许志伟喜欢把事情做到极致。刚认识他的时候,他正痴迷于野生鸟类摄影。但他不像别人那样,只追珍稀动物。总觉得,相对于能够拍到珍稀动物,他更享受这种追逐拍摄的过程。

做过动物摄影的人都知道,相比其他门类,拍动物要艰苦许多。除了对器材要求更高外,需要摄影师有更多的耐心、更多的爱心、更强的体能、更镇定的心理,越挫越勇的意志力……那段时间,他总喜欢和我说拍摄过程中碰到的事。

大过年的,他晃荡在徽州山野,就为了邂逅白腿小隼——传说中“会飞的大熊猫”。

“我跟你说啊,这种小肥鸟实在太可爱了,从表情到形象都像大熊猫。粗短的毛茸茸的腿,能想像它们会飞吗?你看你看这一家子,小鸟在向爸爸妈妈讨吃的,表情多生动……”他手点着照片,絮絮叨叨地说着,就好像那一窝小鸟是他家养的。

所以,在新疆广袤的戈壁奔驰的时候,他时而一指头顶:“看,燕隼!”还没等我从明晃晃的天空中找到芝麻般大的鸟儿,他又一指路边:“等我,我要拍一下。”那是只新疆岩蜥,它出来晒太阳了。蜥蜴是冷血动物,会随着外界气温变化而变化体温。戈壁早晚温差大,这会儿是中午,它就会出洞来晒太阳,让体温上升,活动开手脚后就可以吃东西了。随着他的解说,我看见蜥蜴抬起右脚晒了晒脚底心,隔了一会儿,又抬起左脚晒脚底。

过沙漠的时候,耳边总传来蝉的鸣叫声。我疑惑地望望地上一丛丛的梭梭草,看看远处稀落的红柳,奇怪地问:“怎么会有蝉呢?”“那是响尾蛇尾巴发出的声音,用于警告。”和他出行,就是这么的长见识。只是,见识总是不那么容易得来。

(三)

慢慢地,许志伟又开始从风光摄影和野生动物摄影转向人文摄影,并且,开始成为一个坚定的传统文化的记录者和守护者。

转变的起因,在我看来,还是源于他一次次地去徽州地区拍小鸟、拍老房子、拍油菜花……

“你不知道啊,有一年大过年的,我在山里转,想拍传统的过年风俗。村民碰到我的时候都很同情我,以为我有什么事想不开独自在山里转悠。有个老大爷硬是邀请我去他家过年……”

去了无数次后,他熟悉了那里的乡村,找到了那儿的乡野美食,也找到了流传千百年却渐渐没落的耕读传家、田园理想。

“我去拍老房子,能找到的成片古民居,一年比一年少。心里总是担心,下次再去,这些老房子是不是还在……”许志伟说,这些年,他拍的许多照片都成了“绝片”。与世界各地面临的状况一样,那些曾经散落在乡野间的廊桥、民居、老手艺,那些渐行渐远的乡土中国,那些可以把酒话桑麻,最具体、最地道的人间烟火,或是因为洪水等地质灾害,或是因为无人继承等原因,渐渐消失、失传。

忽然有一天,他的微信上晒出了一封辞职信,脱下了穿了20年的警服,在人到中年之时,离开了自己熟悉的领域,任着性子去做自己喜欢的事情。在很多人眼里这是件充满不确定性的事,但他却说,人生的出场顺序的确很重要,但其实只要不中途退场,尽管去努力好了,最坏的结果不过是大器晚成。

他从手机里翻出一张图表,上面是中国传统村落名单,足足4000多处。“我已经跑了1000多个了。”他说,如果不辞职,就需要认真地上班,那要到几时才能拍完这些村子呀?

(四)

在行走乡村的过程中,许志伟渐渐从一个中国传统文化的门外汉,进化成为专业者。

2014年的时候,他做了个人公号“守艺”,记录他采访和拍摄过的古居建筑、民间手工艺、器物,上至被列入世界保护名录的非遗项目,下至乡野流传千百年的乡村民俗。他说,应该致敬的是,在这个飞速发展的世界里,依然愿意听从内心安排的匠人们,是他们让中国传统手作中的唯一和隽永被重新认知;也应该感谢生活的安排,让我们尚能遇到那些或简约清雅或锦瑟侬华的老房子。它们能幸存下来,有天意百般眷顾,有百姓拼尽人事。哪怕离家千里,数代之后,这些古建筑的存在,总能提醒我们,不忘祖宗来处,记得子孙去向。

一种文化,它展现出的是对生活的全方面渗透。所以,了解和传承中国传统文化,光是关注于器物建筑或是非遗的保护都是远远不够的。

他还是个吃货,他曾经一脸夸张地跟我说:带你去徽州,吃最地道的徽菜,看最原生态的村子,遥想当年风物,山水如斯,伊人不改。

是的,他有資本说这句话。春天的时候,他去乡野采风给我捎来一捆腊笋,炖肉吃后怎么形容呢?就一个字:香。

半年来,我从他的微信看到,他正自由地奔跑在中国的大地上,去敦煌拍莫高窟,去山西五台山拍寺庙,去福建拍土楼……

如果你有他的微信,你会在他的微信上认识中国文化,认识传统乡村,认识我们的乡愁、认识我们的来处与去向。

(本文图片由许志伟拍摄)

I have known photographer Xu Zhiwei for many years. hard working is his most outstanding aspect of his personality as testified by a scene of fifteen years ago I remember so clearly. Xu and I were on an assignment in Xinjiang. We were driving past the Kalamaili Nature Reserve at the edge of East Junggar Basin when we spotted some marmots peeping out at us from a row of small holes in a slope not very far from the highway. It was July and it was scorching. Xu wanted to photograph these lovely rodents. He turned down my suggestion that he stay in the car and take shots through the car window. He stepped out and walked slowly toward the slope. He carried a huge backpack inside which were his camera and other equipment. When he came back into the car, he looked sunburned. His back was all drenched with sweat. He drank a whole bottle of water without a stop. He said disappointedly he had not taken a single shot. The marmots disappeared inside the holes and stayed unseen after seeing him approach.

When I first met Xu Zhiwei, he was a policeman, but he neither patrolled streets nor cracked crime cases. He did a desk job. It was his hobby to take nature photos. Back then he spent a lot of time photographing wild birds. He says what he likes most about outdoor journeys is not the photos he can show. He likes the process. He says a wildlife photographer needs patience, courage, a strong body and a calm psyche. I have learned a lot about his trips and about wildlife.

However, Xu Zhiwei shifted his attention from nature and wildlife to culture a few years now. Part of his attention now focuses on villages that are disappearing. The first step he took in this shifting occurred in the southern Anhui Province some years ago. It was during the Spring Festival time. He was journeying thorough a mountain in a bid to photograph how local people celebrated the traditional Chinese New Year. Villagers he encountered at first looked at him with sympathy, thinking he was wandering aimlessly simply because he had run into some difficulties in life. A grandpa even forced him into home to take part in some Spring Festival festivities. After numerous visits to the region, he became intimately acquainted with local lifestyle. He fell in love with the lyrical rural landscape.

To his alarm, he noticed that it was becoming more and more difficult to photograph complete rows of old houses as they were dismantled at a fast rate. Some old villages he photographed have disappeared or deserted. Many of his village photos are the only ones of their kind in this world. Some photos are the only visual records of the villages that have vanished. He isnt happy about these photos. “Id rather I didnt have them. They had been there for hundreds of years even before the invention of photography. Why cant they continue to exist? If we cant foresee what lies ahead, we need to understand where we came from,” Xu thinks.

Xu Zhiwei has long since become a specialist of Chinese culture. In 2014, he started a public account on a social media where he regularly publishes photos of ancient villages, folk arts and crafts, and objects from rural life.

After working at the police department for 20 years, he made up his mind in the middle of a meeting in August 2019 to resign in order to devote himself to his mission. In his mobile phone is a list of about 4,000 traditional villages across China. He has visited about 1,000. He aims to visit them all. “How could I photograph them all if I hadnt resigned?” He is racing against time, for he has learned from somewhere that averagely 1.6 villages disappear per day in China. With these villages disappearing at this rate, he knows that he wouldnt have the time to cover them all. He hopes to do what he can. Of course, what he wants to photograph is more than these villages. He has a lot to catch up as a full-time photographer. Even before his resignation, he did not have time to photograph some big historical places such as Dunhuang.

Over the past six months, I have followed his journeys across the country. I marvel at what he sees and experiences. Of all the thoughts I have about Xu Zhiwei, one thing is clear: It isnt his capability that makes what he is. It is his choice.