Unexpected encounter of the parasitic kind

2019-11-28HollyMatthewsFlorianNoulin

Holly Matthews,Florian Noulin

Holly Matthews,Florian Noulin,Centre for Applied Entomology and Parasitology,School of Life Sciences,Keele University,Keele ST5 5BG,United Kingdom

Abstract

Key words: Stem cells; Parasites; Transplantation; Therapeutic; Host pathogen interactions

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells are defined by their self-renewal properties,and their ability to differentiate into adult cells[1].They can be classified into two groups according to their biological properties:Pluripotent and multipotent stem cells.Pluripotent stem cells are able to differentiate into any cell type,and are found in the blastocyst,and early embryonic developmental stage[2].Pluripotent stem cells give rise to three germ layers (endoderm,mesoderm and ectoderm) that ultimately produce different organs:cardiac,skeletal muscle or red blood cells for the mesoderm,pancreatic or lung cells for the endoderm,and neuron or skin cells for the ectoderm (Figure 1).Multipotent stem cells are more limited with regards to their differentiating capabilities.While they can differentiate into multiple cell types,they are already polarised down a specific route and can be found in most adult tissues where they replace aged or damaged cells throughout the lifespan of the multicellular organism[3].

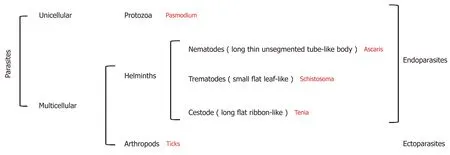

Parasites are organisms that survive by taking nutrients from another organism:their host[4].They represent more than 50% of all animal species[5]and can be broadly divided into three groups:Protozoa,helminths,and ectoparasites (Figure 2).The diseases they cause inflict huge health and socio-economic burden on low income countries[6].Indeed,parasitic infections were considered responsible for 7.2% of deaths globally in 2016[7].

The relationship between parasites and stem cells is becoming increasingly studied(Figure 3).The purpose of this review is to further examine the relationship between stem cells and parasites,specifically looking at parasitic stem cells,how the parasites influence the host’s stem cells,and how these interactions may be exploited clinically.

PARASITIC STEM CELLS

Although unicellular protozoan parasites do not have stem cells,the stems cells of other multi-cellular parasites such as helminths have been studied.Interestingly,one of the earliest references to the term “stem cell” was in relation to the parasitic helminthAscaris megalocephalain the late 19thcentury[8].Thus,it is perhaps unsurprising that some parasite’s stem cells have been used to better understand the regeneration system.

Echinococcus

The tapewormEchinococcusis one such parasite.This organism presents primarily as a zoonosis but can infect humans through animal transmission[9].While the infection can manifest in four distinct forms,only two are relevant to human health:cystic and alveolar.CysticEchinococcusinfection is caused byEchinococcus granulosusand is characterised by the development of hydatid cysts,typically in the liver and lungs.AlveolarEchinococcusinfection is caused byE.multilocularisand is initially asymptomatic,but a primary tumour-like lesion develops in the liver.This form is fatal if untreated.TheEchinococcuslife cycle begins when the adult (located in the intestine of the definitive Canidae host) releases eggs that exit the host in the faeces.Once ingested by an intermediate host,i.e.sheep,the eggs hatch and release oncospheres that pass through the intestinal wall and migrate into different organs.There,the larval forms develop into cysts containing protoscolices:the form that is ingested by the definitive host that evolves into protoscolex.Following ingestion,the protoscolices attach to the intestinal mucosa where they develop into adults.

Recently,Koziolet al[10]proposed to identify germinal cells inE.granulosus.For this,they treated the parasites cells with 5-Ethynyl-2´-deoxyuridine (EDU),a synthetic nucleotide that is incorporated into newly synthesised DNA,to identify cells in proliferation.They noticed that the germinal cells were less proliferative during the protoscolex stage but were reactivated when ingestion by a host was mimicked,highlighting the ability of these cells to remain quiescent while not in optimal conditions.To better characterise this cell population,they proposed to identify potential specific marker genes using the whole mountin situhybridisation(commonly known as WMISH) technique but unfortunately were unsuccessful in this attempt.Notably,germinative cells could not be fully eliminated after gamma radiation treatment and the parasite only showed a delayed growth defect.From all these observations,they concluded that some parasite cells are capable of self-renewal and differentiation into proliferative competent cells.

Figure 1 Diagram of the three human germ layers and lineage fates.

In further work focusing on mobile genetic elements,Koziolet al[11],identified a novel family of terminal-repeat retrotransposons in miniature (known as TRIMs) as potential germline cell markers.Using a computer modelling approach,they identified putative Taeniid (Ta-)TRIMs and confirmed,by using the WMISH technic,that their expression was strongly restricted to proliferative germinative cells.They concluded that Ta-TRIMs could be a good marker of germinative cells inE.granulosus.

Schistosoma

Schistosoma sppare trematode worms that infect mammalian hosts.Eggs are released into a water source in the faeces or urine of the definitive host.The eggs hatch,releasing miracidia that infect aquatic snails.Once there,the parasite develops into a sporozoite and produces cercariae.These are released into the water and penetrate the skin of the definitive host.The parasite then sheds its characteristic forked tail to become schistosomulae and migrates to the veins.The final venule location of the adultSchistosomais dependant of the species.The females lay eggs that migrate through the intestines to be excreted by either urination or defecation[12].

Collinset al[13]in 2013 produced the first report on adult somatic stem cells inSchistosoma mansoni.ComparingS.mansonito already documented worms (PlanarianandEchinococcus),they investigated the possible presence of neoblast-like cells in the parasite.Using EDU labelling,they observed a proliferating population in the mesenchyme of male and female parasites.Similar genes to the ones observed in planarian neoblasts were downregulated after gamma irradiation,which were correlated with a potential stem cell population in the parasite.They confirmed the self-renewal and differentiation potential of these cells using EDU/Bromodeoxyuridine labelling studies and noted that theSm-fgfrAgene seemed to promote the long-term maintenance of neoblast-like cells inS.mansonifollowing RNA interference experiments.In order to better characterise these cell populations,they investigated gene expression following gamma radiation and performed RNA interference[14].They identified 135 downregulated genes,most of which were involved in parasite’s surface cell populations.By focusing in more detail on a specific gene (tetraspanin,TSP-2),they observed that its expression disappeared a couple of days after stem cell population depletion.They proposed that neoblast differentiation was biased towards tegument cells,especially those expressingTSP-2+.

Recently,Wanget al[15]investigated the role ofS.mansonistem cells throughout the different parasite stages,including the snail hosting period (Figure 4).Using single RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) studies,they identified three distinct stem cell populations in the sporozoite stage based on the main expression ofkfl nanos 2andfgfrA,B genes:κ cells expressingkfl+ nanos 2+,cells expressing fgfrA,B+and δ cells expression bothkfl+ nanos 2+andfgfrA,B+.During the asexual stages in the snail,δ cells were found in the embryo,as well as κ cells that were also present in extraembryonic tissues,while the cells were mainly in the parasite’s outer layer and not in the daughter embryo.Notably,a fixed number of κ and δ cells seem to be kept by the parasite while in the mammalian host where they form the source of the previously described stem cells.Another subpopulation of stem cell derived from κ cells and expressingeledhgene (aSchistosome-specific factor) was found in juvenal parasites and named ε cells.These cells can give rise to germline or posterior somatic cells depending on the nanos-1 expression (germline if active).

Figure 2 Diagram of parasite classification.

Parasite and stem cell models

In addition to the study of parasite’s own stem cells,two worm species,PlanariaandCaenorhabditis elegans,although they are not or are only rarely parasitic,have served as important models for parasite stem cell and general stem cell biology,respectively,and will therefore be discussed further.

Planariaare flatworms that are only rarely parasitic.They are typically hermaphroditic but can reproduce by fission[16].These flatworms can be compared to the parasitic trematodeSchistosoma.One example of this is from Collinset al[17],who studied a bioactive peptide in the planarianSchmidtea mediterraneaand used this to identify novel pro-hormones inS.mansoni.

Planarian are able to fully regenerate as they have a population of stem cells named neoblasts[18].Rossiet al[19]identified a group of 60 genes specific to planarian stem cells using microarrays and WMISH,many of which are involved in epigenetics and regulation of transcription.Interestingly,the planarian seems to be a good model for human nervous system regeneration[20]due to the its high degree of conservation with vertebrates.Moreover,Onalet al[21]found that pluripotent genes in human stem cells were conserved in the planarian.Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting coupled with RNA-seq studies,they specifically identified octamer-binding transcription factor 4,NANOG,and sex determining region Y-box 2.This later study proved that planarian organisms are valuable models to better understand human stem cells.

C.elegansis a roundworm belonging to the nematode family.This organism is well known by scientists as it is one of the most studied and best models for fundamental research as summarised in Kevin Strange’s review[22].It has been extensively used as a parasite model[23,24].A better understanding ofC.elegansstem cell biology would allow a better understanding of stem cell biology in general[25].Among the many studies involvingC.elegansstem cells,we can cite the work from Seidelet al[26]who studied stem cell quiescence following starvation,or Noormohammadiet al[27]who showed that TRiC/CCT assembly is linked to pluripotency of human stem cells and resistance to proteotoxic stress inC.elegans.

Parasite stem cells are evidently an interesting topic that is becoming increasingly better studied.Although their strong regeneration capacity is beyond that of their human counterparts,they serve to facilitate our understanding of stem cell capabilities and biology in general.

INTERACTIONS BETWEEN HOST STEM CELLS AND PARASITES

Figure 3 Chart of the yearly number of scientific literature publications including the keywords “stem cells + parasites” over the last 50 years.

Parasites invade and occupy a number of different niches within their host species.Consequently,they interact with stems cells in a variety of ways.Many of the interactions are indirect due to tissue damage caused by the parasite,which trigger host immunity and damage repair mechanisms.Other interactions can be more direct whereby the parasite or soluble parasitic factors directly affect stem cell proliferation.An additional layer of complexity is the ability of certain parasites to manipulate their host by not only inducing stem cell proliferation,but also stimulating differentiation into the parasite’s preferred cell type.Evidence of such interactions will be discussed below.

Insect hosts

As well as infecting humans and other mammals,various insect species are subject to parasitism.In many cases,insects serve as disease vectors transmitting the parasite from one human to another.The parasites often go through developmental stages within their host insect and therefore impact insect fitness and insect stem cell biology.

Mosquitos:The malaria parasitePlasmodiumuses femaleAnophelesmosquitos,which feed on mammalian blood as an intermediate host.Upon consuming a blood meal,the parasite enters the mosquito midgut.Following transversal of the midgut epithelium,the parasite undergoes a multiplication phase and the progeny migrate to the mosquito salivary gland.These parasites are then injected into another human during a subsequent blood meal.During invasion and intracellular migration of the mosquito midgut epithelium,the parasite triggers apoptosis and necrosis of invaded cells[28].Surprisingly,this is not detrimental to mosquito survival.During infection ofAnopheles stephensiwithPlasmodium falciparum,Baton and Ranford-Cartwright (2007)showed that midgut regenerative cells underwent proliferation and differentiation to replace columnar midgut cells.Moreover,the number of proliferating and differentiating cells correlated with the level of midgut cell destruction.This indicates that the mosquito is able to compensate for parasitic damage through proliferative regeneration,inadvertently permitting parasite transmission[29].

Honey bees:A similar protective mechanism to that described for the mosquito was predicted in the honey bee,Apis mellifera.The honey bee endures enterocyte damage during infection with the parasitic microsporidian,Nosema ceranae[30].Despite reports elsewhere that G1/S phase genes were upregulated duringN.ceranaeinfection[31],Paneket al[32]recently showed a reduction in the replicative capacity of intestinal stem cells during infection.Drosophilainfection with the parasitic waspLeptopilina boulardiinduces haematopoiesis through ROS-dependent induction of the Toll/NF-KB and EGFR pathways.L.boulardialso stimulates the preferential differentiation of lamellocytes,increasing their proportion to nearly 50% of all haemocytes.These cells are specifically involved in pathogen encapsulation as well as killing and implicate the existence of a “do or die” mechanism,as survival depends on the neutralisation of wasp eggs before they hatch[33].Evidently,insects have utilised their stem cell response when necessary to permit endurance or destruction of the parasite insult.

Figure 4 Gene expression and localisation of the different S mansoni stem cell populations in the two main hosts.

Mammalian hosts

Helminths:Trichinella spiralisis a nematode parasite that infects many carnivorous and omnivorous animals,including humans,and can be acquired by ingesting cysts from contaminated/undercooked meat[34].Infection of Balb/c mice with parasitic worms such asT.spiralisorHeligmosomoides polygyrus(a mouse model for human helminth infections) have been shown to induce changes in stem cell proliferation within intestinal crypts of their hosts.T.spiralisleads to small intestine inflammation and an initial increase in epithelial stems cells (Ki-67-positive) and/or transient daughter cells (day 2 post infection).This alters the architecture of the intestinal crypt and causes an upward shift in the proliferative zone[35].In another nematode parasite,Trichuris muris,such alterations are considered to facilitate expulsion of the parasite from its inter-epithelial niche[36].However,duringT.spiralisinfection,the proliferative response is not sustained.The Ki-67-positive population decreased by days 6-12 postinfection,while the number of secretory Paneth cells increased (possibly due to differentiation).This may be advantageous as secretory products from Paneth cells,such as antimicrobial peptides and proteins,are considered important for host protection against luminal microorganisms[35].Conversely,adult intestinal stem cells were shown to be repressed in Balb/c mice infected withH.polygyrus.During infection,granuloma associated crypts exhibited loss of the adult intestinal stem cell markersLgr5-GFPandOlfm4,whileLy6a(which encodes stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1)),was upregulated.Nippostrongylus brasiliensis,a nematode parasite that does not invade intestinal tissue,did not induce Sca-1.This suggests that upregulation of Sca-1 is a specific response to crypt injury induced byH.polygyrus.Immune cell-derived interferon gamma (IFNγ) was critical for the granuloma associated crypt response.Interestingly,foetal stem cell markersGjalandSpp1were shown to be upregulated in the granuloma associated crypt,implicating a novel mechanism to repair intestinal crypt disruption.

Toxoplasma:Toxoplasmais a single-cell,protozoan parasite and is the causative agent of toxoplasmosis.Most human infections are asymptomatic,but the disease is more severe in immune compromised individuals and infants,if the mother were to become infected during pregnancy.Cats are the definitive host and shed the oocysts in their faeces which can be accidentally ingested by humans and other mammals or birds[37].T.gondiiinduces apoptosis and inhibits the differentiation of neuronal stem cells.These interactions are considered major contributors to congenital neuropathology.Various markers of apoptosis were found to be upregulated during the coculture ofT.gondiitachyzoites and neuronal stem cells.These experiments used a trans-well culture system,which only permits the passage of parasitic soluble factors,not the parasite itself.Consequently,inhibition was attributed toT.gondiiexcretedsecreted antigens (Tg-ESAs).The disruption of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis occurs in many diseases and can lead to the activation of cell death pathways.Wanget al[38]showed decreased apoptosis following pre-treatment with the endoplasmic reticulum stress inhibitor TUDCA,implicating the involvement of the endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway in the interaction betweenTg-ESAs and neuronal stem cell apoptosis.Tg-ESAs were also found to inhibit the differentiation of neuronal stem cells into neurones and astrocytes.This was determined by measuring the concentration of cell markers,specifically βIII-tubulin and glial fibrillary acidic protein.These decreased in a dose-dependent manner.A reduction in β-catenin and interactivity effects betweenTg-ESAs and wnt3a (an activator of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway) implicated the involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway,an important differentiation pathway in neuronal stem cells[39].Further work implicated the virulence factor Rhoptry protein 18 as a partial mediator of the endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis and cell differentiation (Wnt/β-catenin) pathways[40].

Plasmodium:Once injected into the human hostviathe bite of the femaleAnophelesmosquito,the parasites invade hepatocytes and multiply,forming liver schizonts[41].These burst releasing merozoites,which invade erythrocytes,and begin the asexual reproductive cycle.During early malarial infection,both MSCs and HSCs are produced in the bone marrow (BM) and subsequently migrate to the spleen.Interestingly,adoptive transfer ofP.berghei-induced MSCs conferred resistance toP.bergheiin naive mice.MSCs were shown to migrate to the spleen,enhance proinflammatory cytokine production (specifically interleukin 12 [IL-12]),inhibit antiinflammatory cytokines (specifically IL-10),and inhibit the accumulation of T-regulatory cells,which are induced by malaria as an immune evasion mechanism.Adoptive transfer of MSCs in late stage infections,however,did not alter disease progression[42].An early haematopoiesis response is considered protective to the host,to counteract erythrocyte loss caused by parasite maturation in red blood cells.Unfortunately,the response cannot sustained during the course of malaria infection leading to the common disease-associated pathophysiology of anaemia[43].One suggestion is that there is competition for the production of erythropoietic and immune cell,both derived from pluripotent stem cells[44].Interestingly,during low oxygen conditions the kidneys produce erythropoietin,which in turn stimulates erythropoiesis.During mouse infection withP.vinckeiorP.chabaudi,but notP.berghei,further erythropoiesis could be stimulated by exposing infected mice to high altitude conditions (hypoxia) in a decompression chamber.This indicated that the infection withP.bergheihad already saturated the maximal erythropoiesis response.The initial increase in HSCs during early infection may be due toP.berghei’spreference for invasion of reticulocytes.However,cellularity (total number of nucleated cells) and subsequently erythropoietic capacity in the BM decreased during the course of malaria infection.Despite enlargement and an increase in cellularity,the spleen does not compensate to meet the erythropoietic and hemopoietic needs of the host,which leads to anaemia.Although there are reports that pluripotent stems cells remain in G0 and are therefore protected,the lethality and severity of anaemia during malaria infection may be determined by irreversible damage to the self-renewal capacity of hematopoietic stems cells,as observed with chronic leishmania infection[45].

Leishmania:Leishmania spphave a broad spectrum of interactions with various host stem cell lineages.Although macrophages are their primary host,they have been shown to be capable of infecting a variety of cells including different types of stems cells bothin vitroandin vivo[46-49].Allahverdiyevet al[47]showedin vitroinvasion of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells byL.donovani,L.major,L.tropica,andL.infantumparasites,raising potential concerns about stem cell transplantations and parasite transmission,which is discussed in more detail later.BM-derived MSCs (BMMSCs) were also shown to be vulnerable toL.infantumandL.donovaniinvasion in anin vivomouse model.This was confirmed by confocal microscopy and co-staining with antibodies for parasites and MSCs (CD271+/Sca1+) isolated from both the BM and spleen of infected mice.Interestingly,the authors not only visualised this invasion eventsex vivo,but determined the viability of the amastigotes identified in BM-MSC CD27+CD45 cells by inoculating the infected cells into an axenicin vitroculture system.Then promastigote forms were detected.Since MSCs have potent drug efflux pumps,the proposed purpose of this interaction is the potential avoidance of drug-induced death.This is considered particularly important for latent infections that occur despite treatment.Such stem cells niches could also serve as a “hide-out”for parasites during asymptomatic infections.

As well as the modulation of host stem cell proliferation,following the direct invasion of stem cells,tissues infected withLeishmaniaparasites have also been reported to display alterations in host cytokine/chemokine expression and stem cell proliferation.Dameshghiet al[50]in 2016 isolated macrophages and adipose-derived MSCs from mice that were either sensitive or resistant toLeishmania.Isolated cells were placed,in various combinations,in a trans-well system.After 72 h of co-culture the MSC chamber was removed and the macrophage supernatant was replaced before challenge withL.majorpromastigotes.These macrophages,now considered MSC-educated,showed a reduction in phagocytosis,nitric oxide,IL-10,tumour necrosis factor alpha production and an induction in inflammatory cytokines in response toL.majorinfection.This response was independent of prior sensitivity toLeishmania(although the magnitude of the response did vary between treatment-group combinations).This implicates MSCs as the sensors and switchers of immune modulation and supports the potential of stem cells as a treatment for leishmaniasis.Local alterations in hematopoietic activity have also been reported in tissues harbouringL.donovaniamastigotesin vivo[51].Infection leads to an increase in progenitor cell frequency in the blood,and a correlation was observed between hematopoietic activity and parasite proliferation in the spleen and BM.Tissue-specific regulation of cytokine and chemokine expression was also observed,with an increase in those associated with monocyte and granulocyte maturation from multipotential precursors.Leishmania-infected stromal cells also display an enhanced capacityin vitro,through cytokine regulation,to support the differentiation of regulatory dendritic cells from hematopoietic progenitor cells[52].The recombinant heat shock protein 70,from a related kinetoplastid parasiteTrypanosoma cruzi,was also shown to have an immune-stimulatory effect on the maturation of dendritic cells from BM precursors.Remarkably,dendritic cell maturation occurred in the presence of the recombinant protein alone,fused to the KMP11 antigen as well as a 242-amino acid protein fragment[53].This again could have implications for therapy.As the main source of immune cells,it is not surprising that BM-hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells are activated duringLeishmaniainfection.This is consistent with the stress response to other acute infections[54].However,L.donovaniwas shown to be capable of host manipulation by skewing HSC expansion to the differentiation of non-classical myeloid progenitor cells.Interestingly,cells produced in this manner were not only the preferred target of the parasite but were also more permissive toLeishmaniainfection,providing evidence of parasite manipulation[54].Acute infections can give rise to such expansion that cannot be sustained during chronic infection.Using adoptive transfer of IFNγ sufficient CD4+T cells into immune-deficient mice,Pintoet al[55]in 2017 showed that chronic stimulation of HSC expansion,by this pathway,leads to hematopoietic exhaustion.In this instance,the reservoir of long-term HSCs irreversibly loses quiescence and enters into an active cell cycle,where they eventually lose their self-renewal capacity.During chronic infections,an effective anti-parasitic response is therefore at the expense of the reservoir of quiescent LT-HSC hematopoietic fitness.The importance of this trade-off for sufferers of life-long chronic infections is yet to be determined.

Evidently,parasites can develop a range of complex interactions with their host’s stem cells by modulating their expression and fate.Although the growing body of research into this area in recent years (Figure 3) has meant that we know more now than ever before,the field remains in its infancy.Most of the aforementioned studies were conducted in insect or mouse models,as obvious technical and ethical issues limit humanin vivoinvestigations.Due to the complexity of parasite life cycles,often having distinct development stages in multiple host tissues,studies into general parasite biology during human infection are also limited by thein vitroculture systems we have available.However,as ourin vitrocapabilities for stem cells production have expended parasitologist can utilise stems cells in order to recreate and study parasite development within a variety of host tissues that were previously inaccessible.Examples of such studies are detailed in Table 1.The availability of these valuable model systems will not only permit a better understanding of parasite biology but may open up new avenues for parasite treatment.

STEM CELL AND PARASITE THERAPIES

Stem cell therapies have become increasingly more applied as potential cures for important diseases such as liver injuries,muscle degeneration or anaemia[56].Thesetherapies aim to replace dysfunctional cells or tissues with the transplantation of newly generated and functional stem cells.In addition to these applications,a new field of use for stem cell therapy has recently emerged:Parasitic treatment.The aim of these treatments is not to directly target the parasite itself but to help the patient fight and recover post infection,as we will discuss further in this section.

Table 1 Table of stem cell classes used to model parasite infections

Trypanosoma

The first parasite infection that we will cover is the kinetoplastid parasiteT.cruzi.This parasite is responsible for Chagas disease,that affects up to 7 million people,and predominantly occurs in Latin America[57].The disease is curable if treated during early stage of infection,however treatment efficacy decreases with time.There are two distinct infection stages:Acute and chronic.The former stage can last up to 2 wk and,though the patient may have a high parasitaemia,the symptoms remain relatively mild and non-specific[58].The latter stage can be subdivided into determinate and indeterminate phases.The determinate phase is marked by an equilibrium stage where host and parasites co-exist with no damage.Following an unknown mechanism,up to 30% of the patients will switch to the indeterminate phase.During this stage,Chagas disease-associated severe complications such as gastrointestinal or chronic heart diseases occur.Chagas heart disease remains the most severe and prevalent complication (45% of the chronic patients),which explains why it has been more extensively described.It is characterised by an extensive fibrosis of the myocardium that can evolve into chronic heart failure[59].The treatment for Chagas heart disease cases are symptom dependent but can eventually lead to a heart transplant.This has further associated consequences and due to immunosuppression could lead to the reactivation of the parasitic infection[60].It is thus very important to find an alternative method to repair cardiac tissue affected by the parasite.Soareset al[61]in 2004 were the first to use MSCs to treat heart failure following a parasitic infection.They transplanted BM of a healthy mouse into a mouse model of Chagas heart disease and observed a reduction in inflammation and fibrotic areas by 80% and 90% respectively.Interestingly,BMC treatment was shown to affect the myocardium transcriptome by decreasing the expression of upregulated genes involved in inflammation and fibrotic events inT.cruzi-infected mice[62].One striking example is the strong downregulation of Galectin-3.Galectin-3 is a protein that is expressed by macrophages and correlates with inflammation in the mouse model of Chagas heart diseaseviaits involvement in the induction of collagen production,proliferation of cardiac fibroblast and T-cell apoptosis suppression.This work implicates Galectin-3 as a potential therapeutic target and highlights the possible use of BMC injection as antiinflammatory and anti-fibrotic treatment of Chagas’s heart disease.

Following the initial success with mouse-models (reviewed by Carvalhoet al[63]) the next step was to evaluate whether such results could be achieved during human infection.The first clinal trial took place on a 52-year-old man suffering of heart failure due toT.cruziinfection[64].Purified mononuclear cells,isolated from healthy BM,were injected into the patient and an improved ventricular function was observed 30 d post-transplantation.This first success lead to additional studies which further expanded to a multi-centre randomised clinical trial.Over a total of 183 patients were treated with BM mononuclear cells in conjunction with granulocytecolony stimulating factor.Unfortunately,no improvement in cardiac function was observed[65].Although the results with the BM-derived mononuclear cells were not as good as expected,the use of a different type of stem cells,MSCs,did yield some interesting results and showed immunomodulatory properties as well as the potential for use in chronic chagasic cardiomyopathies[66].Notably,only a small fraction of injected MSCs actually migrated to the heart in a Chagas mouse model.Indeed,nearly 70% could be found in liver,lungs,and spleen.Nevertheless,a reduction of the right ventricular dilatation was observed after MSC transplantation in Chagas mouse models.A further study showed that MSC treatment could influence gene expression and more especially the extracellular matrix protein laminin γ1 that was upregulated in infected mice compared to the MSCs treated ones[67].Interestingly,two antagonist factors (the pro-inflammatory INFγ and the anti-inflammatory IL-10) that were upregulated in infected mice are down-regulated after MSC treatment.The proinflammatory stromal cell-derived factor-1 gene was also upregulated after MSC treatment,which could be correlated to the attraction of additional stem cells to the damaged area.More recently,Laroccaet al[68]did not observe any cardiac function improvements following adipose-derived MSCs but a decrease in fibrosis and inflammatory cells.Evidently,there has been some difficulty in defining effective stem cell therapeutic targets,and further translating these from Chagas heart disease mouse models to the human disease system,but the value of such a treatment warrants further research into this area.

Leishmania spp

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic infection that can take different forms dependent on the parasitic strain.Three distinct forms affect different targets:the cutaneous form (that can be caused by almost anyleishmania spp) affects the skin with the presence of lesions,the mucocutaneous form (caused byL.DonovaniandL.infantum) leads to a partial or full destruction of mucosal membranes around the mouth,nose or throat while the visceral form affects the liver,BM,and spleen[69].Leishmaniasis symptoms can also be due to an alteration of the host immune response.Knowing that MSCs can modulate the immune response[70],it seems reasonable to use these cells as therapy against cutaneous leishmania as Pereiraet al[71]investigated.Unfortunately,they did not observe any protective effect,post-MSC injection,in a mouse model of cutaneous infection and even reported an increase in parasitic burden dependent on the route of MSC administration.This increase was correlated to an increase of IL-10 producing CD4+and CD8+T cells in the spleen.Of note,Il-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine that can limit the ability of macrophages to kill intracellular organisms and the lack of T-cell-derived IL-10 enhances protection fromL.majorinfection in mouse as previously described[72].Besides cutaneous leishmaniasis,stem cell therapies could be applied to otherLeishmaniastrains such as the visceral and mucocutaneous forms of the disease.StudyingL.major(responsible for the visceral form),Dameshghiet al[50]obtained promising immunomodulatory results from a cell-based assay,nevertheless the results still have to be translated to anin vivosystem.

Schistosoma

Schistosomiasis is caused by a parasitic trematode.These worms remain in the host’s blood vessels where the female lays the eggs that are the primary cause of pathology during chronic disease[73].Proteolytic enzymes released by the eggs trigger a T-helper type 2 response that can lead to the fibrosis of affected tissues[74].There are two main types of schistosomiasis infection:Urogenital schistosomiasis caused byS.haematobiumand hepatic schistosomiasis caused byS.mansoni,S.intercalatum,S.japonicum,andS.mekongi[75].The urogenital schistosomiasis can lead to fibrosis of the bladder and lower ureters and can even evolve to kidney failure.The hepatic schistosomiasis shows two distinct forms:Fibrotic hepatic disease and early inflammatory.The fibrotic hepatic disease (Symmer’s pipestem fibrosis) is caused by the deposition of collagen in the periportal spaces,leading to the tissue’s hypoxia.Studies have already been conducted to investigate the potential of MSCs to cure these symptoms and a decrease of liver fibrosis has been observed in treated mouse models ofS.mansoni[76].Moreover,El-Shennawyet al[77]recently showed that a treatment with BM-MSCs significantly decreased the granulomas size and the expression of alpha-smooth muscle actin (a fibrosis factor) in hepatic stellate cells.The anti-fibrotic effect of the MSCs was not limited to these features and it included the inhibition of collagen deposition,a downregulation of transforming growth factor β1 and an upregulation of matrix metalloprotease 9,a matrix metalloprotease that leads to hepatic stellate cells apoptosis.As hepatic stellate cells are involved in the hepatic fibrosis process during liver injury[78],early injection of MSCs to trigger their apoptosis may lead to a more efficient cure.MSCs have also been used to treatS.japonicummouse models using single injections or in combination with praziquantel (current drug treatment against schistosomiasis) and a recovery of the spleen and liver was observed due to the inhibition of the collagen deposition[79].Another stem cell source has been tested by Elkhafifet al[80]in 2011 who used CD133+human umbilical cord blood stem cells to trigger the production of new blood vessels in order to promote vascularisation.This neo-vascularisation created a permissive environment allowing better survival of damaged cells.

Plasmodium

The Plasmodium parasite,the causative agent of malaria,is an important public health threat.Symptoms of the infection are initially non-specific and include headache,fever and fatigue[81].How the infection progresses will then be defined as uncomplicated or severe (complicated) malaria.The severe form can be fatal with symptoms including consciousness,convulsions,bleeding,anaemia,renal impairment and pulmonary oedema[82].The erythrocyte is one niche exploited by parasite in the human host and during a 48 or 72 h erythrocytic cycle (dependent on the species)the parasite continuously occupies,destroys and invades yet more red blood cells,thus having a huge impact on blood cell homeostasis.Knowing this feature,the use of HSC could be an interesting therapeutic approach.Indeed,Belyaevet al[83]in 2010 identified,in the BM ofP.chabaudiinfected mice,a new subset of haematopoietic progenitors triggered by IFNγ signal.The injection of these healthy atypical HSC progenitors within infected mice showed a greater clearance of infected erythrocytes leading to a decrease in infection-associated anaemia.MSCs isolated from the spleen ofP.bergheiinfected mice,could be transplanted to naïve mice prior their exposition toP.berghei[42].Interestingly,these MSCs produced protective cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor alpha and IL-1β that decreased the production of haemozoin(product from the erythrocyte haem degradation).This helps to counteract host evasion mechanisms used by the parasite as hemozoin inhibits macrophages and decreases the number of Treg cells in the spleen[84].These cells can be used to treat cerebral malaria,a severe complication ofP.falciparuminfection,characterised by neurological symptoms including coma,convulsion,drowsiness and confusion and can affect spleen,kidneys and lungs[85].Treatment of BM-MSCs improved the clearance of parasitised erythrocytes,increased the regeneration of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (specific phagocytic cells) and increased the number of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the brain.In parallel,lung inflammation was reduced,by limiting collagen deposition,and the number of neutrophils,and amount of malaria pigmentation was decreased while the mesangial architecture of the kidney was restored[86].Despite all these improvements,no reduction of the brain damage was observed.

Stem cell therapies have the potential to significantly alter the way in which we treat parasitic infections (Figure 5).The transplantation of stem cells to aid the recovery of damaged organs remains a really interesting addition to traditional parasitic cure methods.However,these methods and techniques are still in their infancy,and the affordability of stem cell-based therapies will be a significant factor in their uptake,particularly in developing countries where these neglected tropical diseases predominate[87].

Parasitic infections and transplantation

The future availability of stem cell therapies were predicted to be revolutionary for the cure of multiple disease as emphasised by the recent increase in interest in this research area and the number (7150 with the term “stem cells”) of clinical trials registered with clinicaltrials.gov.Nevertheless,only HSCs have been so far approved by United States Food and Drug Administration to serve as cure therapy[88].They are mainly used,through BM transplantation,to cure blood disorders such as leukaemia or myeloma.Prior to any transplantation,donations are screened for any potential infection.Some screens such as HIV 1+2,hepatitis C,hepatitis B,syphilis,human T-lymphotropic virus 1+2 are mandatory in United Kingdom[89].However cytomegalovirus,malaria,Trypanosoma cruziand West Nile virus remain simply additional.These additional screens are only performed if a donor risk has been identified.Multiple parasitic infections have been identified in recipient’s posttransplantation (as discussed below).However,the immunosuppressive medication following an allogenic transplantation makes the patient more sensitive to opportunistic parasitic infections and must be considered as a potential source/ route of infection without the availability of donor pre-screens.

Figure 5 Parasitic infections and stem cell therapies targeting different organs.

Though Leishmaniasis does not appear on the list of infectious pathogens screened prior to transplantation,its ability to survive within an intracellular environment by creating a suitable niche for replication[90]remains a threat.Indeed,although the parasite primarily invades phagocytic cells,i.e.macrophages,the amastigote form has been found in fibroblasts[48],hepatocytes[49]and amniotic epithelial cells[91].The potential ofLeishmaniato survive in MSC has been recently investigated by Allahverdiyevet al[47]who were able to observe anin vitroinfection of adipose-derived MSCs byL.tropica,L.donovani,L.majorandL.infantum.

Of note,several cases of leishmania infections post MSC transplantations have been documented[92,93]though the presence of the parasite in the transplant was not proved.Several hypotheses could be raised,i.e.an infectious sand fly bite post transplantation,a latent infection in the patient or a re-activation of the opportunist parasite due to the immunosuppressive treatment.ThePlasmodiumparasite has also been described in the BM of an infected individual[94]and has been reported to be capable of invading HSC progenitors[95].Moreover,the parasite,once in the human host,remains in the liver for 7 to 10 d and sometimes for a longer period as the hypnozoite form.For these reasons,reports of malaria infection following transplantation are not surprising.Indeed,Martín-Dávilaet al[96]recently reported patients infected byP.malariaeandP.ovaleafter liver and kidney transplantations.Parasite transmission can also occur after BM transplantation as described in a recent case even when the donor was not classified at risk[97].

Toxoplasmais a parasite that does not appear on the list of pathogen screens prior to transplantation as they are unlikely to be found in stem cells.Nevertheless,several cases of toxoplasmosis infected patients post-HSC transplantation have been described[98]mostly as an opportunistic infection following the immunosuppression treatment post-transplantation.Another parasite taking advantage of the lower immune defence post stem cell injection is cryptosporidium,which has also been identified in patients post transplantation[99].

It is thus necessary to consider parasites during the screening process pretransplantation and not only based on donor recent travel history to endemic areas.The follow up post-transplantation monitoring should also not be neglected as opportunistic infections represent an important threat.

CONCLUSION

As can be seen from this review,the two seemingly distinct fields of stem cell research and parasitology are in fact closely entwined.Not only do multicellular parasites have stem cells of their own,but certain parasites exploit stem cells to create niches either within their host stem cells,or by modulating host stem cell activity to create a more habitable environment.The use of stem cells as therapies to treat either the parasitic diseases or,more commonly,the sequalae associated with the infection,is becoming increasingly more studied.The presented literature allows us to highlight the importance of considering stem cells as important targets for parasites and not underestimate this relationship from a clinical point of view.

杂志排行

World Journal of Stem Cells的其它文章

- Colon cancer stemness as a reversible epigenetic state: Implications for anticancer therapies

- CRISPR/Cas system: An emerging technology in stem cell research

- Cytokine interplay among the diseased retina,inflammatory cells and mesenchymal stem cells - a clue to stem cell-based therapy

- Developments in cell culture systems for human pluripotent stem cells

- Monitoring maturation of neural stem cell grafts within a host microenvironment

- Ameliorating liver fibrosis in an animal model using the secretome released from miR-122-transfected adipose-derived stem cells