Analysis of global momentum transfer due to buried mine detonation

2019-11-18HeiderDenefeldAurichErnstMchInstituteErnstZermeloStr79104FreiburgGermny

N. Heider , V. Denefeld , H. Aurich b Ernst-Mch-Institute, Ernst-Zermelo-Strße 4, 79104 Freiburg, Germny

b Ernst-Mach-Institute, Am Christianswuhr 2, 79400 Kandern, Germany

Keywords:Improvised explosive device Vehicle protection Occupant loading

ABSTRACT The emergence of improvised explosive devices (IED) significantly extended the spectrum of possible threat mechanisms to military vehicles and their occupants. Especially buried high explosive (HE)charges lead to new and originally not investigated loading conditions during their detonation. It is the interaction of the embedding geomaterial with the detonation products that leads to a strongly increased global impulse transfer on the vehicle with following high accelerations on the vehicle occupant. This paper presents a comprehensive approach for the analysis of occupant loading.In a first step,we present the so called ring technology which allows the experimental determination of the locally resolved specific impulse distribution on a vehicle floor due to buried charge detonation. A complementary method is the use of scaled model vehicles that allows the determination of global vehicle loading parameters such as jump height or vehicle accelerations.Both techniques were used to study the influence of burial conditions as burial depth, embedding material or water content on the impulse transfer onto the vehicle. These experimental data are used to validate material models for the embedding sand or gravel materials.This validated material description is the basis for numerical simulation models used in the assessment of occupant safety. In the last step,we present a simulation model for a generic military vehicle including a Hybrid III occupant dummy that is used for the determination of biomechanical occupant exposure levels.Typical occupant loadings are evaluated and correlated with burial conditions as HE mass and global momentum transfer.

1. Introduction

Buried mines or IEDs present severe threats to military vehicles and their occupants.The effects of these threats depend not only on the detonation of the high explosive (HE) mass and the following expansion of the detonation products, but also strongly on the confining geomaterial and the burial conditions. Main influential factors are the charge mass, burial depth, stand-off and confining geomaterial.

An important observation is the fact that the interaction of the detonation products with the surrounding soil or gravel leads to a significant momentum transfer increase onto the loaded vehicle.This gives rise to global acceleration effects onto the vehicle and the occupants. The assessment of occupant safety needs a complete understanding of the occurring phenomena beginning with the momentum transfer mechanism to the vehicle up to the evaluation of biomechanical occupant exposure levels.

Classical military anti-tank-mines are shallow buried and have HE masses in the range from 2 kg up to 10 kg. Their effect is localized either through the formation of a projectile with subsequent perforation of the vehicle structure or local deformation of the vehicle floor.Results concerning the quantitative determination of the impulse transfer onto a vehicle from these mines can be found in[1e3].One of the earliest papers with experimental results about the local impulse distribution is[4]where steel cylinders were used as momentum trap.These data were the basis for the development of empirical analytical models to describe the specific impulse transfer due to buried charges [5]. They parameterize the burial conditions and can easily be implemented in simulation tools to allow very quick first assessments of vehicle loads [6,7]. A further improvement in the physical description can be achieved with numerical simulation models that explicitly describe the physical processes of HE charge detonation, interaction with the surrounding geomaterial and final effects on the vehicle structure[8,9]. Special attention has been given to a detailed description of the sand or gravel embedding material [10,11].

With the appearance of IEDs, additional phenomena in connection with deeply buried charges of large masses (up to several hundred kg)became of interest[6,12e15].It turned out and was partially unexpected that this type of threat caused a significantly increased global momentum transfer. Hence, there was the need for a better understanding of this loading process.Influencing factors are:charge mass,embedding material(e.g.sand,gravel,and clay), density, water content, saturation, and depth of burial,ground clearance and vehicle shape. Scientific work concentrated on the analysis of the charge embedding geomaterial preparation and the correlation of burial conditions with the impulse transfer[16e19].In many test devices,only the global momentum transfer on a large-area structure was examined.For a better understanding of the loading process, locally resolved information about the specific impulse distribution on a structure is necessary [4,20,21].In Ref. [22] we presented a new test technology based on a ring arrangement with each individual ring used as a momentum trap at the corresponding local position. With this method, systematic variations of burial conditions can be analyzed and correlated with the momentum transfer.As an example,we show in the following the importance of water content and saturation on the specific momentum distribution. With the help of scaled vehicle models,global loading effects can be analyzed. The applicability of this technology to the design of global protection systems was shown in Ref. [14], where the physical basis of the concept of dynamical impulse compensation(DIC)was analyzed.This concept is based on ejection units that are mounted onto the vehicle.After detection of the IED detonation these units are initiated and eject dummy masses compensating the global impulse transfer from the IED onto the vehicle. With the help of the scaled vehicle approach in combination with numerical simulation, it was shown that the occupant loading could be significantly reduced.

The dependence of the impulse transfer on the depth of burial is experimentally determined with these scaled model vehicles. The ring technology and the scaled vehicles provide detailed information about the principal physical effects and are used as a validation tool for empirical models and numerical simulations. Numerical simulations can be used to transfer the presented results to real military vehicles. Full scale experimental testing of occupant loading due to buried charge detonations is done with Hybrid III dummies according to the specifications defined in Ref. [23]. For numerical simulations,corresponding Hybrid III software dummies were developed and are available in the LS-Dyna finite-element code. In Ref. [24], the application and validation of these software dummies for occupant safety analysis is demonstrated. In the following, it is shown how the validated simulation models are used to correlate IED burial conditions with biomechanical occupant exposure levels.

2. Ring technology

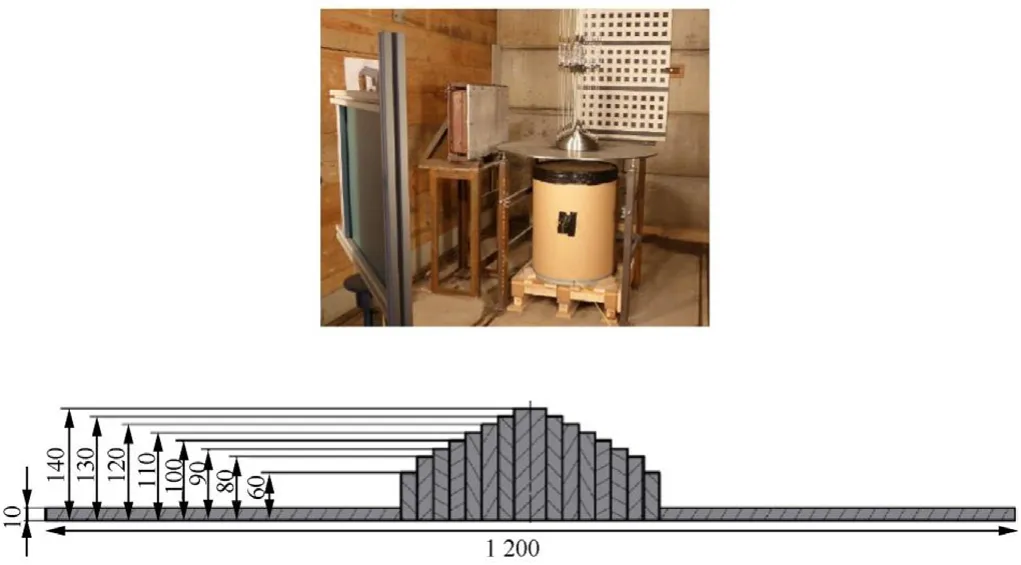

Fig.1 shows the experimental set up for the determination of the local specific impulse. The HE charge is placed in a sand filled barrel under defined conditions.Above the barrel is the ring system that is used as momentum trap.It consists of 8 rings with different height and an additional outer steel plate with a diameter of 120 cm and a thickness of 1 cm.The dimensions are chosen to ensure best separability of the different rings in the pictures from X-ray diagnostics.After detonation of the charge,the rings are accelerated and obtain after 2e3 ms a constant velocity. This velocity together with the ring mass and base area determines the specific impulse.The ring velocities are determined with redundant measuring techniques: X-ray diagnostic, high speed camera and photonic Doppler velocimetry(PDV).The sand barrel has a diameter of 63 cm and a height of 80 cm and is replaced for each test and newly filled with sand again.The PETN charge is of cylindrical shape and has a mass of 84 g with a diameter of 59.2 mm.The depth of burial of the explosive charge varies from 23.2 to 116 mm.The distance between the sand surface and the ring structure is 139 mm.More details on the experimental set up can be found in Ref. [22].

Fig.1. Ring technology device for the measurement of the local specific momentum distribution.

3. Influence of water content on impulse transfer

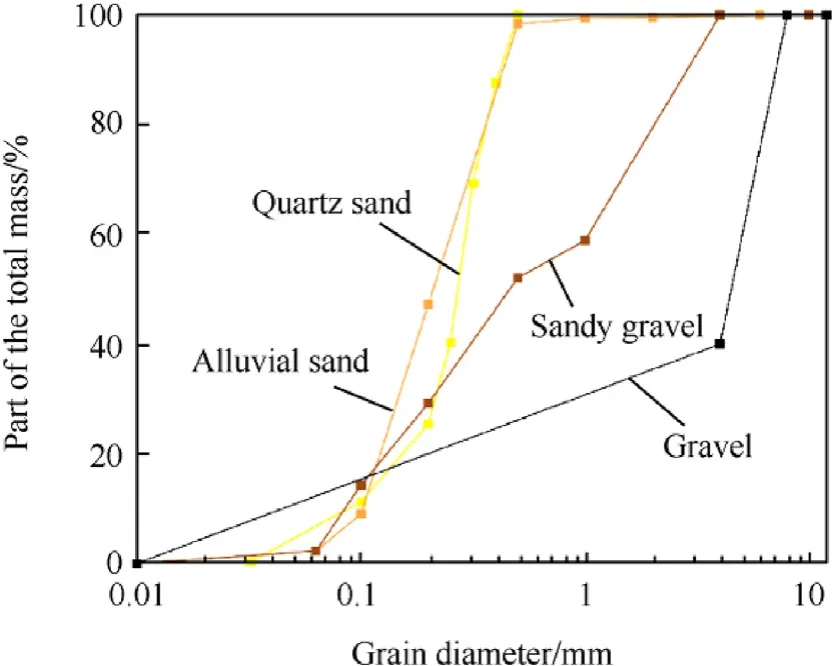

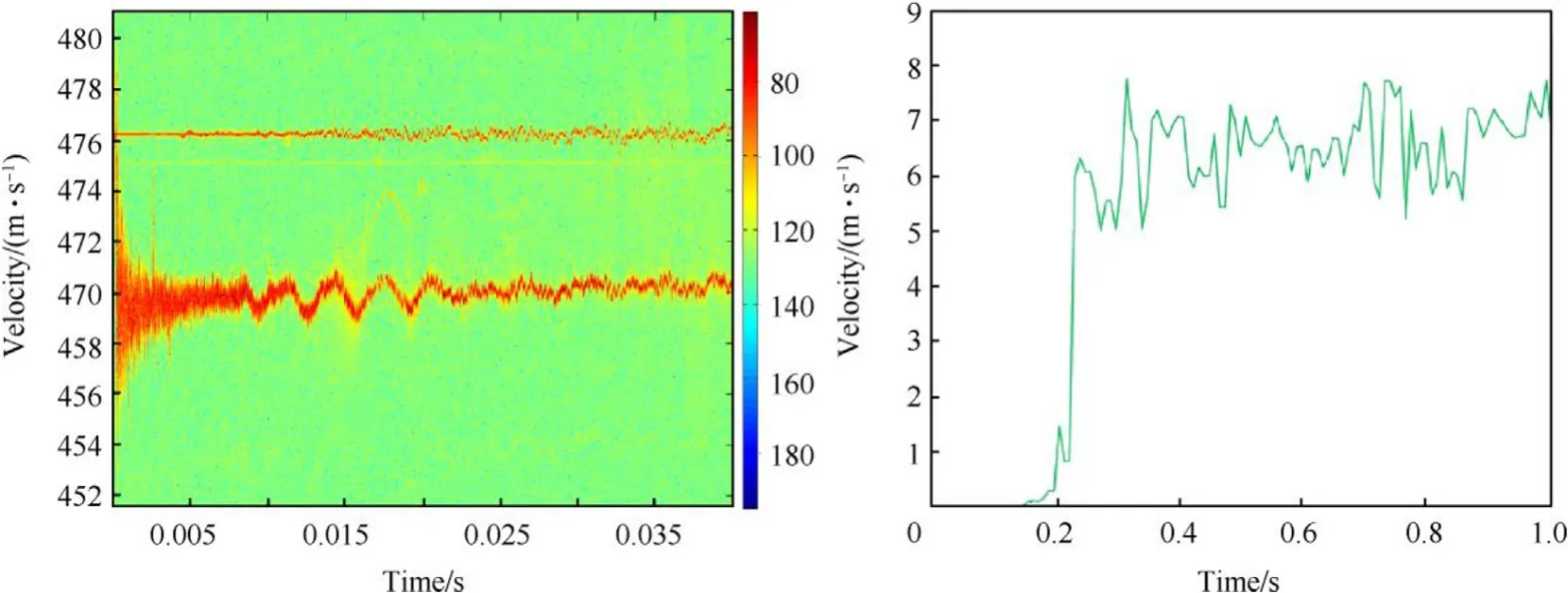

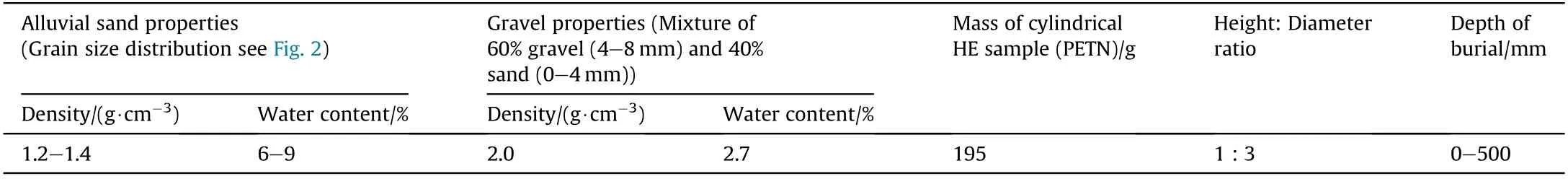

The presented test set up was used to analyze the influence of different burial conditions on the specific momentum distribution.Three different types of sand materials were used for the following tests: quartz sand, alluvial sand and sandy gravel with the corresponding grain size distributions in Fig. 2. The grain size distribution was obtained experimentally by the use of several sieves with different mesh sizes. Quartz sand and alluvial sand are from one supplier and show a very similar grain size distribution, with the largest grain size of 0.5 mm. Sandy gravel has a size fraction with significantly larger grains,up to 4 mm and corresponds to a scaled material according to the specification given in Ref. [23]. An additional coarser gravel was used for the tests with scaled model vehicles. It consisted of a coarse fraction of grains with diameters between 4 and 8 mm and a fine sand fraction with grains lower than 4 mm (approximated distribution included in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Grain size distribution for alluvial sand, quartz sand, sandy gravel and gravel.

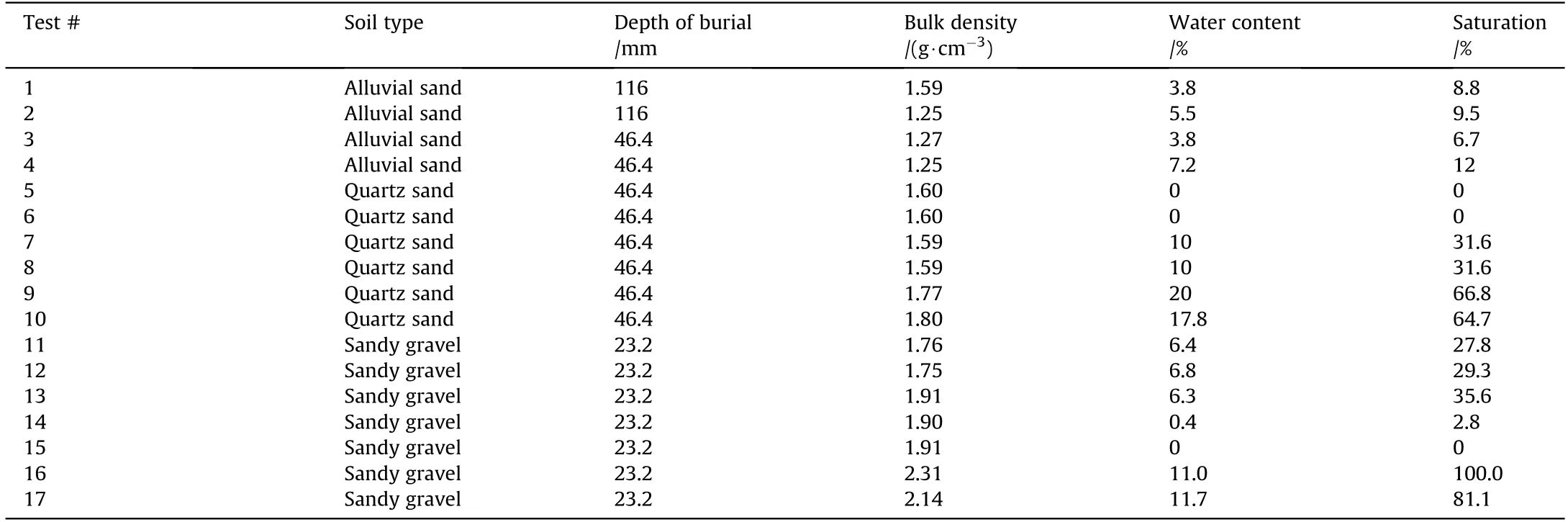

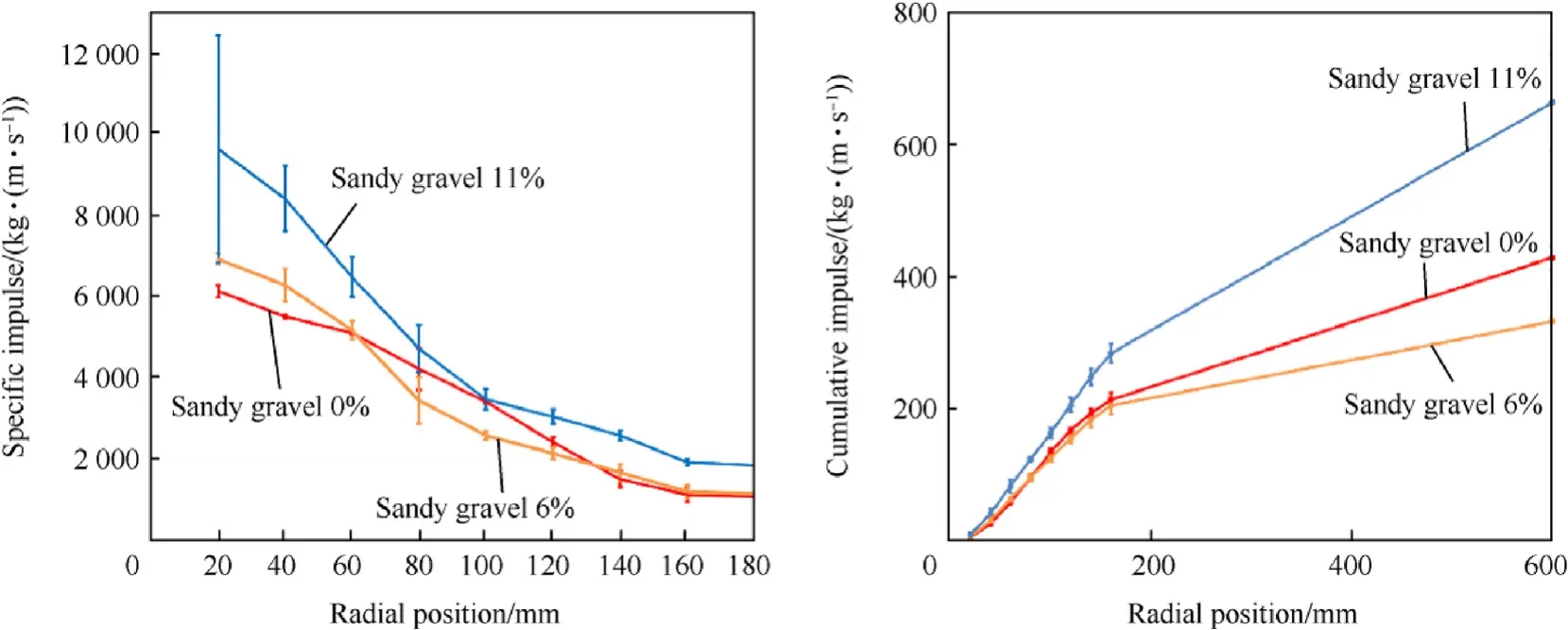

An important parameter is the water content that determines together with the saturation the density of the geomaterial. The homogeneous preparation of the sand material requires a defined method for setting up the test arrangement. In a first step,exactly measured fractions of completely dry sand and water are mixed,leading to the desired water content. Then the test barrel is filled layer by layer and compacted with a layer thickness of 10 cm.In the end, an additional material sample is taken from the sand surface for an independent experimental determination of the water content.Comparison and agreement with the prescribed value ensure an evenly sand preparation. The water content was varied in the range from 0 to 20%with corresponding saturation values from 0 to 100%. Table 1 summarizes the experimental test conditions. The depth of burial of the HE charge was varied between 23.2 mm and 116 mm. A typical PDV velocity measurement for a selected ring from test 16 is shown in Fig.3.The analysis of the original frequency spectrum gives the detailed information about the time dependent velocity increase of the ring.In this example,the final ring velocity is 7 m/s and is reached within 0.3 ms. Experimental results for the specific impulse as a function of the radial distance and the integrated cumulated impulse for sandy gravel are summarized in Fig. 4, with the water content being the varied parameter. The distributions show a typical bell-shaped behavior with a concentration effect directly above the detonating charge. A significant increase of the momentum transfer can be observed for the testswith 11% water content. Comparison of 0 and 6% water content does not give a clear indication for a dependence on water content.Only the addition of sufficient water to reach nearly complete saturation will lead to an increase of the momentum transfer. The cumulated impulses integrated over a range of 120 cm confirm this observation.

Table 1 Test program and the corresponding measured soil parameters.

Fig. 3. Spectrogram from the Photonic-Doppler-Velocimetry measurement (left) and zoom on the first millisecond of the signal (right) (Test #16).

Fig. 4. Specific impulse distribution and corresponding cumulated impulse for sandy gravel with variable water content.

Important parameters that determine the momentum transfer are the water content,density and saturation.Unfortunately,these parameters are interconnected and cannot be varied independently. For a physical based assessment we therefore represented the results in Fig.5 as a function of all 3 parameters.It can be seen that the water content alone will not lead to a significant impulse transfer because we observed water content values of 20%without any appreciable impulse increase.On the other hand the diagrams with the saturation and density dependence show the clear impulse increase of a factor 2.5 referred to the dry sand.The increase could be assigned either to the nearly complete saturation reached in the sand water mixture or to the density increase up to 2.3 g/cm3.

Experimental data concerning the local distribution of the specific impulse are the basis for validation of numerical simulation models in the field of vehicle protection.This applies particularly to the validation of the material models for sand and gravel and is a requirement for successful simulation of occupant loading in military vehicles due to buried HE charge detonations. The material model for sand used in this paper is based on[11].There a material model for sand is presented that includes a porous equation of state, pressure dependent yield surface, density dependent bulk sound velocity and pressure dependent shear modulus. The material model was applied to the simulation of anti-tank mine effects[25]and was validated and calibrated for the sand materials used in our experiments,where we determined the local distribution of the specific momentum.In Ref.[22]we compared specific momentum distributions from our experiments with corresponding numerical simulations and it was shown that the agreement is within an error range of 5%.

4. Scaled model vehicles

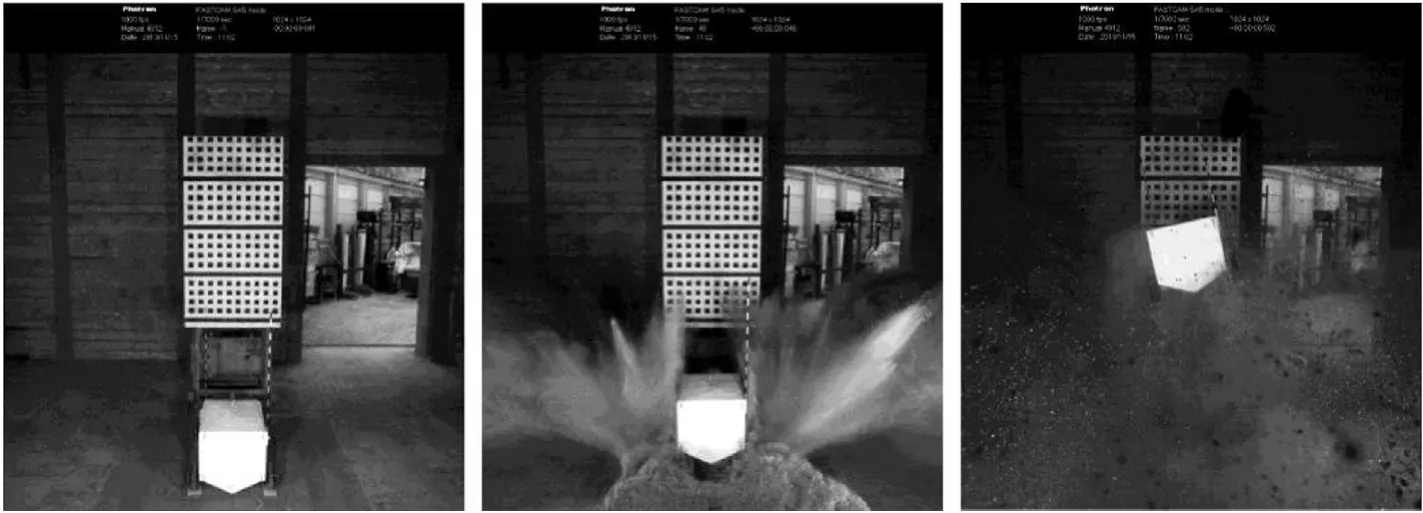

Another approach for the analysis of buried charge effects is the use of scaled model vehicles.Compared to tests with original sized vehicles,expenses are significantly lower and parametric variations of burial conditions are feasible.In contrast to the ring technology,there is no local resolution of the vehicle loading but it provides data about global parameters as acceleration or the influence of vehicle geometry on the loading history. Scaled vehicle models were successfully used for the analysis of V-shaped vehicle designs and global protection systems as dynamic impulse compensation DIC[14].The model vehicle used in our tests is shown in Fig.6 with the global dimensions: mass 150 kg, length 100 cm, width 50 cm,height 50 cm and ground clearance 13.9 cm. Starting point of the analysis was a protected vehicle in the mass range of 9 tons. A scaling factor of 4 was applied and lead to the dimensions of our model vehicle.But scaling laws allow of course the extrapolation of the model data with other scaling factors and to other original vehicle dimensions. This generic vehicle was then used for an assessment of the influence of burial conditions on the impulse transfer.

5. Influence of depth of burial on impulse transfer

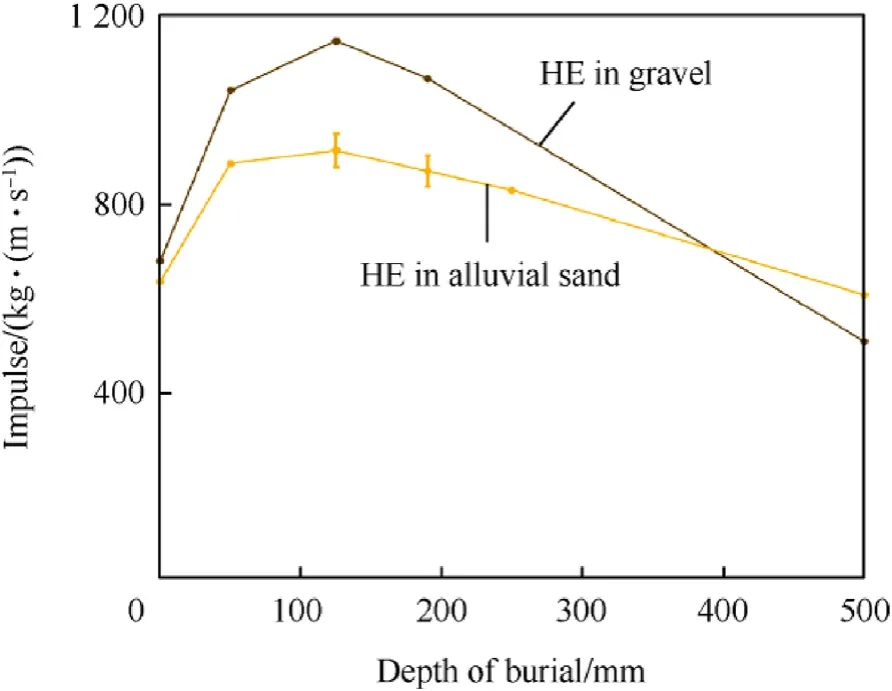

Of special interest is the depth of burial that determines the confinement of the HE charge.The burial conditions chosen for this test series are listed in Table 2.The burial depth is varied from 0 to 50 cm;all other test parameters are kept constant.Fig.7 shows the experimental results for the global momentum transfer on the vehicle as a function of the burial depth for alluvial sand and gravel.It is clear that there is an optimal burial depth around 125 mm,which results in a maximum loading of the vehicle. The optimal burial depth is not sensitive to the used embedding material, but the momentum transfer depends on the density and therefore on the mass of the confining geomaterial. The sand cover acts similar as the confinement in a fragmentation warhead. It is a balancing process between large sand cover mass and high sand velocity that leads to the maximum impulse transfer created by the charge detonation. The results show that the selection of test conditions for the development of new protected vehicles depends not only on the charge mass, but also on other parameters as depth of burial,the selected embedding material and the water content. Exact knowledge of these influencing parameters is necessary to guarantee reproducible test conditions for vehicle technical acceptance tests.

Fig. 6. Scaled model vehicle and jump height measurement due to buried IED detonation.

Table 2 Burial conditions for the scaled vehicle test series.

Fig. 7. Total momentum transferred onto the vehicle as a function of the depth of burial for a HE charge embedded in alluvial sand and gravel.

6. Simulation of occupant safety

The final assessment of IED threats must treat the occupant loading levels inside the vehicle. The occupant experiences the global acceleration of the vehicle structure due to the momentum transfer from the charge detonation. The forces are transferred through the whole vehicle structure including possible damping mechanisms, the seat construction and the connection between seat and vehicle structure. Optimization of all these components can lead to significant reduction of the occupant exposure. Numerical simulations can significantly improve these design optimizations during the development phase of new protected military vehicles. Different commercial codes are suitable for this application, the simulations in the following were performed with LSDyna 3D version 7.

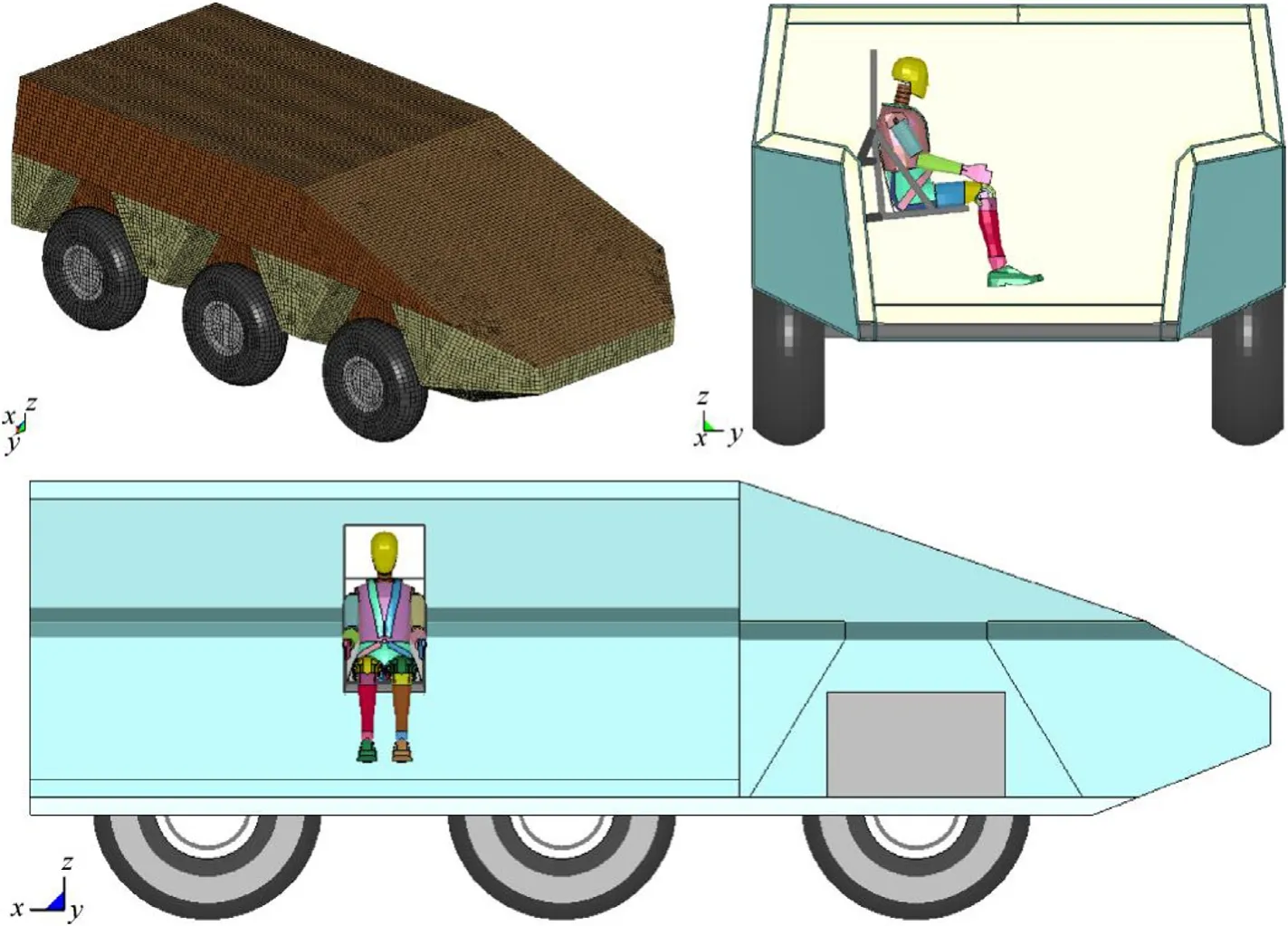

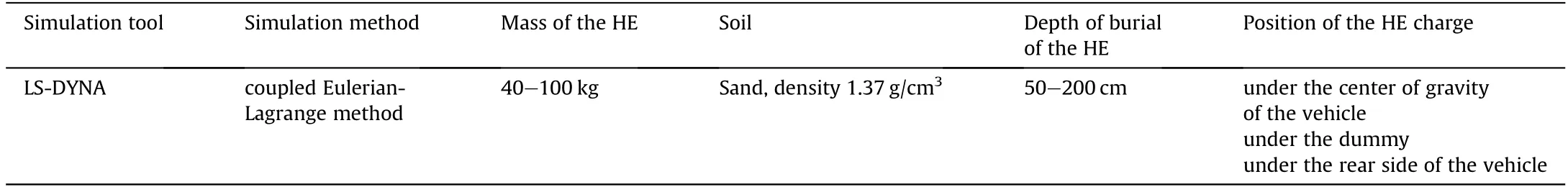

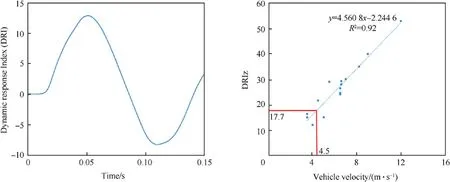

For the numerical simulation of occupant safety, we chose a generic protected combat vehicle with a global mass of 24 t.A finite element model was developed that included the essential structural parts of the vehicle and with typical dimensions(length 8 m,width 3 m,height 2.5 m).The vehicle is represented by a Lagrange model with 72,000 shell elements. The embedding material with the HE charge and the surrounding air are represented by a Euler model with 1.3 million solid elements. A mesh convergence study has been made and a mesh size of 50 mm has been chosen which is sufficient to ensure validity of the results while maintaining a reasonable simulation time. The detonation process is simulated with a complete EulereLagrange coupling method. The time to perform the simulation is about 20 h, with a parallelized computation on 16 cores. To evaluate the occupant loading, a software Hybrid III dummy was used, positioned in a generic seat construction and connected to the side walls of the vehicle. With the help of the Hybrid III dummy, detailed evaluations of the forces,accelerations, moments and DRI values for the spinal column loading acting on the occupant can be determined.The actual loads can be compared with threshold values for defined injury risks to identify dangerous loading ranges.Fig.8 shows the FE model with Hybrid III dummy, seat and vehicle structure and in Table 3 the range of burial conditions and parameters used for the analysis are given.Parametric variations of the IED detonations were performed and the occupant loads determined.In the following,we evaluated the DRI (Dynamic Response Index) value that is a measure for the spinal column loading. It is obtained by solving a differential equation which models the lumbar spine as a lumped spring-shock absorber system with the time dependent accelerations acting on the occupant as input variable. The DRI is defined in terms of a dimensionless maximum spinal compression derived from the solution of the differential equation.For the load case of a 40 kg HE charge buried in 50 cm depth, the corresponding DRI values as a function of time are shown in Fig.9.The maximum value is 12.9 and is reached after 50 ms. A threshold value for DRI related to a 10%risk of AIS 2 þ injuries is 17.7 [24] and is not reached for this load case. For a systematic assessment, we performed a series of numerical simulations with different burial conditions, concerning charge mass and burial depth.For each simulation,we determined the global vehicle velocity and the resulting DRI value for occupant loading. It turned out that there is a correlation between the DRI values and the global velocity change of the vehicle (as a measure for momentum transfer). We identified a nearly linear relation between DRI and velocity change (see Fig. 9). For the parameter range that we covered in our analysis,it can be seen from Fig.9 that a global velocity of 4.5 m/s leads to the critical value of 17.7 for the DRI. Global velocities higher than 4.5 m/s thus will lead to significant occupant injuries.The presented numerical simulations can be applied to many different problems in the design process of new vehicles, starting with optimized hull shapes for momentum transfer reduction up to the assessment of occupant safety.

Fig. 8. Generic vehicle model with the Hybrid III dummy model occupant attached on a seat at the side of the vehicle.

Table 3 Parameters for the simulation of the occupant loading.

Fig. 9. Example of a DRI signal for a 40 kg HE charge embedded under 50 cm sand (left) and correlation between the DRI and the maximum upwards vehicle velocity (right).

7. Conclusion

A consistent strategy for the evaluation of global vehicle and occupant loads due to IED detonations is presented. Emphasis is given to the analysis of buried charges and the global impulse transfer onto the vehicle. In the first step, the ring technology is used for a complete experimental determination of the impulse transfer to a loaded structure. The laboratory tests allow the variation of all burial conditions as embedding material,depth of burial and sand conditions like water content.As an example,we showed the influence of water content and saturation on the impulse with a significant increase with fully saturated sand. In addition, scaled vehicles can be used for a better understanding of global effects like accelerations or vehicle shape variations(V-shaped vehicle hull or global protection systems).The importance of the depth of burial of the charge on the momentum transfer was demonstrated with an optimum burial depth for highest impulse effect. The last step concerned the assessment of biomechanical loads on the vehicle occupants that were determined with the help of validated simulation models. Special attention has to be given to physical based material modelling of the embedding sand to describe the correct impulse transfer on the loaded structure.This was ensured through calibration of the simulation models with the validation experiments with ring technology and scaled vehicles. The numerical simulations of occupant loads allow a detailed evaluation of forces,accelerations and DRI values. After comparison with threshold values,a statement about injury risks for the occupant can be given.The method does not rely on full scale tests with expensive original vehicles,but requires only small scale tests with HE charge masses up to several hundred grams and validated simulation models including a physical based material description of the embedding material.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the German test range WTD-91 GF-440 in Meppen for funding this work.

杂志排行

Defence Technology的其它文章

- 31st International Symposium on Ballistics, Hyderabad, India, 4e8 November 2019

- Modeling of the whole process of shock wave overpressure of freefield air explosion

- Experimental studies of explosion energy output with different igniter mass

- Investigation on the influence of the initial RDX crystal size on the performance of shaped charge warheads

- Bore-center annular shaped charges with different liner materials penetrating into steel targets

- Deformation, fragmentation and acceleration of a controlled fragmentation charge casing