GUESTS OF HONOR

2019-11-11

Meizhou is a city that the global Hakka diaspora can call home

世界客都梅州:離乡的人们是“客”,久别的故土是“家”

The humid, sub-tropical spring climate of southern China surrounds me upon my arrival at the Meizhou Meixian Airport, along with the babble of Hakka Chinese. Although its unintelligible to Mandarin speakers—and I could barely understand a word—I have the strangest feeling of being back among family.

Meizhou (梅州), an inland city of 4.37 million in the northeast of Guangdong province, got its name back in 971 from the nearby Mei River, which was in turn named after the plum blossoms along its banks. Nestled among hills, rice terraces, and plateaus, Meizhou has always been a city of comings and goings: the final stop on the southward migration of the Hakka people; the starting point of their later exodus to Southeast Asia; and for me, the end of a long search for my own familys origin, as well as the start of another journey to discover our place in this singular diaspora.

I first learned of the Hakkas homeland from my father in 2010, when I started to take a deeper interest in my ancestry. Information, though, was rather limited. Our clans genealogical record, or zupu (族谱), had been lost in a flood, and my father only knows small parts of the story of how my great-grandfather had arrived in Indonesia in the early 1910s and opened a tapioca factory.

There was, though, another piece of ancestral identity that he managed to retain—the Hakka dialect. My father and his siblings still speak Hakka at home, though their variety is different from the other Hakka dialects in China. They did not pass the dialect on to my generation, but I knew the name of my great-grandfathers ancestral village from the inscription on his gravestone, plus another name that my father gave me—Meizhou, the “capital” of Hakkas around the world.

The Hakka, known as the Kejia

(客家, “guest family”) people in Mandarin, are not officially considered a separate ethnic group from the Han majority in China. Originally residents of northern Chinas Yellow River plains, the Hakkas distinct identity and culture have been shaped by at least five mass migrations in their history: fleeing the Xiongnu invasion at the end of the Han dynasty, war and famine during the Tang, the Jurchens conquerors during the Northern Song, and finally the Mongols during the Southern Song.

This fourth exodus brought the Hakka, whod been loyalists fighting on behalf of the Song, to Guangdong. There, government chroniclers distinguished the “masters” (主), or the areas original settlers, from the newly arrived “guests” (客) who had to make their homes in the mountainous land near Meizhou. Like the Jews in Europe, Chinas “guest families” became renowned for their business sense, and many continued migrating to Guangdong and Fujians coastal regions, Taiwan, and Hainan, as well as Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and other countries, as merchants, laborers, and refugees.

Today, Guangdong is still home to 60 percent of the 80 million Hakkas around the world; 95 percent of all overseas Hakka—close to 30 million people—trace their ancestry to the province. Meizhou welcomes thousands of “root-seeking” returnees each year, and even the local football team is known as the Meizhou Kejia. As my taxi took me across one of several bridges straddling the Mei River, I was looking forward to tasting pickled Hakka yamien (腌面) noodles, a perennial snack on my familys table, in its home and original form.

After checking into a hostel, I took off to traverse the Old Town on the lookout for lunch. The central Zhongshan Road is lined with arcade-houses, or qilou (騎楼), residential buildings with a recessed unit on the ground floor to protect shoppers from the rain. A familiar sight in Chinese diaspora communities in South and Southeast Asia, these structures made their first appearance in Meizhou in the early 1930s, built by emigrants who had succeeded abroad and returned to build up their hometown.

In the daytime, these structures house businesses carrying a mix of products typical of the more traditional southeast: Chinese medicine, local specialties, and ceremonial goods. Quite a few sell zha yuyuan (炸芋圆)—shredded taro shaped into a circle, and deep-fried. Shops selling ceremonial wares stand out due to the red products on their shelves, including lanterns, red envelopes, decorative firecrackers, and banners. They also provide services such as writing couplets for the New Year or weddings, and invitation cards.

Steam billowing from a vast pot in front of a restaurant caught my eye. Within minutes, the owner, an elderly woman who enthusiastically attempted to communicate with me in the local dialect, ladled up a piping bowl of niang tofu (酿豆腐)—boiled tofu filled with ground meat. The story behind this savory dish is a well-known example of the Hakkas adaptability: Tofu was one of their substitutes for flour after migrating to the rice-eating south.

My next destination was the Hakka Park (客家公园), home to the Hakka Museum and Huang Zunxian Memorial Hall, dedicated to a well-known Hakka diplomat of the Qing dynasty. The museum, unfortunately, was closed for renovation, but the descriptions state that it is the biggest museum of Hakka culture in China, and offers a comprehensive view of the Hakkas origin, their customs, their emphasis on hard work and high achievement, and the “enclosed-houses” (围屋) customary of Hakka villages—structures where the whole clan lived together, and were protected against bandits and hostile locals in areas where they settled.

As a Hakka growing up in Indonesia, some of these descriptions struck a chord with me: My hometowns Bandung Hakka Association, for example, continues to recognize extraordinary achievements by members of the community in business and entrepreneurship at its annual Chinese New Year dinner. Meanwhile, at home, my family often prays to our ancestors, and my father always emphasized the importance of education, a principle he inherited from my grandfather.

The global Hakka community, too, is full of luminaries whove credited their success to their Hakka identity, from Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen to Singaporean president Lee Kuan Yew. Another notable Hakka was Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, the first ethnically Chinese governor of Jakarta, who received a multitude of domestic and international awards for his achievements in governance, but faced discrimination throughout his life from native Indonesians. Such histories are woven into the identity of itinerant peoples: One well-known example is the Hakka-Punti clan wars, armed conflicts between the Hakka and Cantonese between 1855 and 1867.

In the evening, I head to the Old Town again in search of street snacks. At nighttime, the neighborhood of quiet family businesses is transformed by lights on the qilous pillars that make the beige walls glow gold. Below these, plastic tables and benches from the restaurants spill into the qilous pedestrian corridor, which are packed with customers shouting their orders into the narrow shops. Im forced to shift back and forth between picking my way between the tables, and walking among the swarm of motorcycles on the road.

Overwhelmed by the vast selection of rice noodle soup, rice noodle rolls, milk-boiled egg custard, fried dough-sticks, and beef entrails (牛雜), I take the easy option and choose two shops with the longest lines—both “time-honored brands”—and end up trying entrails for the first time. A mix of bite-sized innards served with a sweet-and-savory dipping sauce on the side, the delicacy is eaten with toothpicks, and is a common after-school snack among the Cantonese.

I dont find the yamien I had been looking for until next mornings breakfast. The chewy noodles mixed with pork oil, mashed garlic, and aromatic green onion remind me of home, and I realize how much of my heritage has been communicated by cooking. Despite some adjustments for the ingredients available in Indonesia, I marvel at finding the unmistakable taste of my familys yamien so far from home, and feel another surge of pride for the Hakka ability to adjust to their surroundings without losing the essence of their identity—and continue to feed their families, from generation to generation, wherever they live.

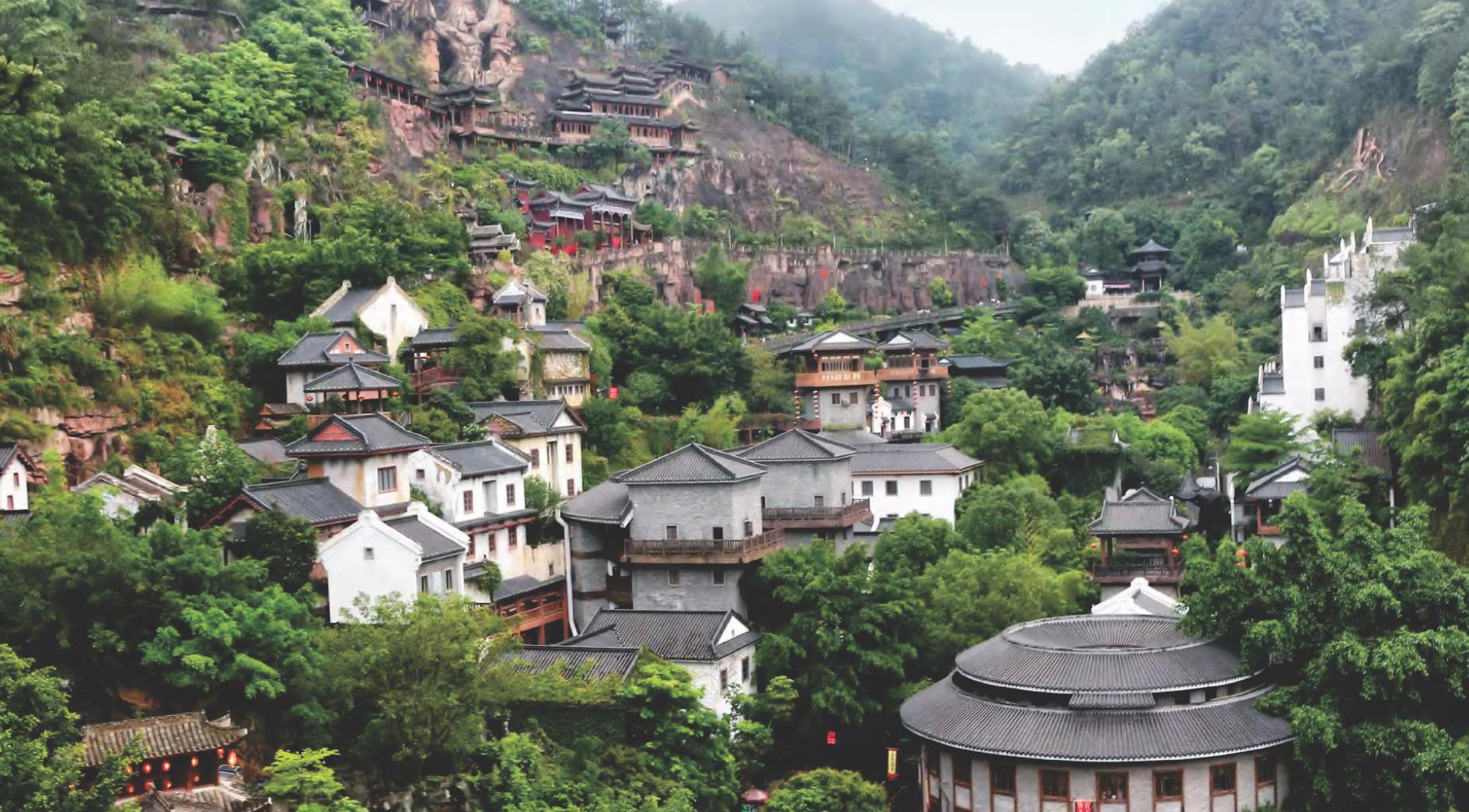

My great-grandfathers home village, Jiaoling (蕉嶺), is 48 kilometers north of urban Meizhou. Because of difficulty finding transportation, I decided to save it for another trip, when I plan to bring my family along. For now, I settle for Ketianxia, or “Hakka World,” a 2,000-hectare theme park located 6 kilometers outside the city. One of its main attractions is a replica of a Hakka village, displaying traditional architecture such as the circular tulou (土楼)characteristic of Fujian, and the Guangdongs local weilongwu (围龙屋), semi-round houses which are on the verge of extinction.

Like authentic Hakka villages, these replicas are constructed into the hillside and beside water for good feng shui. Elsewhere, the park has lifelike statues of Hakkas hard at work and demonstrations of arts like shange (山歌), or “mountain song,” in Hakka dialect. One exuberant Meizhou custom I was sad to miss, but look forward to next time, is the annual “Burning the Fire Dragon” ceremony in Fengshun county. Its said that 300 years ago, a dragon descended from heaven and brought rain to Hakka villages during a drought; now, every Chinese New Year, the local clans parade a paper dragon strapped with firecrackers, which are let off while men dance underneath the shower of sparks.

As the sun slowly set, I head down the mountain to watch a performance of Hakka culture, showing the traditional life of a Hakka: Birth, farm work, marriage, and funeral. As the lights of Ketianxia illuminate the night sky like fireflies, I mulled over words my father would say to me and my siblings when we were growing up: “Remember, wherever we go, we will always be the guest.”

The phrase used to puzzle me—Id always assumed he meant that the Chinese were not fully accepted in Indonesia—but now I know that guest status can itself be an identity; a source of pride and strength; and a place to which to come home.