A chemotaxis model to explain WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow of WHIM mouse model

2019-11-02AiKiYipAkhilBlhnerLeonrTnHngLiongRuiZhenTnKrlBlninFrnoiseBhelerieLiGunNgKengHweeChim

Ai Ki Yip, Akhil Blhner, Leonr D.L.Tn, K Hng Liong, Rui Zhen Tn, Krl Blnin,Frnoise Bhelerie, Li Gun Ng,e,*, Keng-Hwee Chim,*

aBioinformatics Institute (BII), A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research), Biopolis, 138671 Singapore; bSingapore Immunology Network (SIgN), A*STAR (Agency for Science, Technology and Research), Biopolis, 138648 Singapore; cSingapore Institute of Technology, Dover Drive, 138683 Singapore; dINSERM UMR-S996, Laboratory of Excellence in Research on Medication and Innovative Therapeutics, Université Paris-Sud, 92140 Clamart, France; eState Key Laboratory of Experimental Hematology, Institute of Hematology & Blood Diseases Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, 288 Nanjing Road,Tianjin 300020, China

Abstract

Keywords:Cell migration, Cell traction force, CXCL12 sensitivity, CXCR4 internalization, WHIM syndrome

1.INTRODUCTION

Neutrophils are white blood cells that play an important role in the host defence against pathogenic microbial agents.Under resting conditions,98%of the mature neutrophils in the body are stored withinthebonemarrow,withapproximately2%ofthetotalmature neutrophils distributed in the blood stream and tissues.1,2Upon exposure to inflammatory stimuli,neutrophils are rapidly mobilized from the bone marrow into the circulation,and are recruited to the site of inflammation where they carry out their functions and promotetissueremodeling.3Thedistributionofneutrophilsbetween bone marrow and blood compartment is mediated by egression and retention signals provided by chemokines CXCL2 and CXCL12,respectively.4In bone marrow,CXCL12 constitutively expressed by stroma cells promotes neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow through interaction with CXCR4.5Moreover, the CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling axis also activates several signaling processes such as cell migration and proliferation.5,6

At the molecular level, CXCR4 activation leads to phosphorylation of the C-terminal receptor tail, recruitment of β-arrestin and clathrin-mediated endocytosis,leading to receptor desensitization.7,8The endocytosed receptor is either recycled back to the cell membrane or degraded in lysosomes.1,9CXCR4 internalization and receptor desensitization are important in returning signaling to basal levels even when CXCL12 stimulus persists.10Resetting cellular output responses to pre-stimulus levels is referred to as CXCR4 internalization adaptation process.11The time taken for the adaptation process is termed as the CXCR4 internalization adaptation time.Cellular adaptation processes allow neutrophils to dampen signaling in the presence of stimulus,and be poised to detect and respond to further changes in chemokine concentration as cells navigate their extracellular environment.

Defects in neutrophil mobilization from the bone marrow into circulation leads to recurrent infections, as evinced by patients with the Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections, and Myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome.4WHIM patients carry heterozygous mutations in the CXCR4 gene resulting in a 10 to 19 amino acid truncation of the receptor's carboxyl-terminus(C-ter tail), the region important for β-arrestin interaction.7,8These patients therefore do not internalize activated CXCR4 efficiently, resulting in prolonged gain-of-function signaling responses.5-8In the context of chemotaxis, a longer CXCR4 adaptation process may lead to the inability to adjust migration properties set by local CXCL12 migratory source.It is,therefore,unclear how a prolonged CXCR4 adaptation time would lead to neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow.

In this report, we have characterized the mechanochemical properties of WT and WHIM neutrophils and show that neutrophils isolated from WHIM mouse model are primed for cell migration.These mutant cells exhibit higher traction stresses,faster migration speed, and form more lamellipodia on stimulation with CXCL12 as compared to WT cells.WHIM neutrophils are also characterized by larger initial increase in cell migration speed upon ligand stimulation, which decreases more slowly over time as compared to WT neutrophils,suggesting both increased CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 and a longer CXCR4 internalization adaptation time.We therefore proposed a mechanochemical model of the CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling in the bone marrow to explain how these two parameters increase WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow.

2.METHODS AND MATERIALS

2.1.Mice

Mice (8-12 week old) were bred in the Biological Resource Centre (BRC) of A*STAR, Singapore, and maintained under pathogen-free conditions.LysM-GFP expressing enhanced GFP under the LysM promoter was kindly provided by T.Graf(Centre for Genomic Regulation, Barcelona, Spain).12WHIM Gain-of-function CXCR4 mutant mice(crossed with LysM-GFP mice) were generated as previously described.13All mouse experiments were performed as per Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the BRC.

2.2.Isolation of bone marrow cells

Femurs of LysM-GFP or WHIM mice were dissected out and bone marrow cells were harvested by flushing with PBS containing 3% FBS (Serana Europe GmbH, Pessin, Germany).Red blood cells were lysed using commercial-grade RBC lysis buffer(Thermo Fisher Scientific,Carlsbad,CA)and resuspended in RPMI (Hyclone, Uppsala, Sweden) containing 10% FBS.Isolated bone marrow cells were plated on polyacrylamide substrate,allowed to rest for about 2h at 37°C,5%CO2before imaging.Neutrophils were identified by the high GFP expression.

2.3.Fabrication of polyacrylamide substrates

For measurement of cell migration speed and cell traction stress, neutrophils were seeded on 6.2 kPa polyacrylamide gels functionalized with 50μg/mL fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St.Louis,MO)and 10μg/mL type I collagen(rat-tail,Thermo Fisher Scientific).The polyacrylamide gels were fabricated based on previously published protocols.14

Briefly, glass bottomed four wells chambered coverglass(Thermo Fisher Scientific) were treated with silane solution(2% acetic acid [Schedelco, Singapore] and 1.2% 3-methacryloxypropyltrimethoxysilane [Shin-Etsu Chemical, Tokyo,Japan]) for 30min at room temperature and washed with ethanol.After the chambered coverglass was air-dried,2.5μL of pre-polymerized polyacrylamide gel solution (3% acrylamide[Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA], 0.13% N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide[Bio-Rad], 100mM N-acryloyl-6-aminocaproic acid [Tokyo Chemical Industry,Tokyo,Japan],0.72%0.2μm red fluorescent beads [Excitation and emission wavelength of 580 and 605nm respectively] [Thermo Fisher Scientific], 0.1% ammonium persulfate [Bio-Rad] and 0.1% N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine [Bio-rad]) were added into the silanized coverglass and covered with another non-silanized coverglass (5.5×11μm).After polymerization, the polyacrylamide gels were covered in MES buffer(0.1M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid,0.5M sodium chloride, pH 6.1 [Sigma-Aldrich]) overnight at 4°C,before the non-silanized coverglass was carefully removed.To immobilize fibronectin and collagen on the ACA gel surface,the gel surface was treated for 30min at room temperature with 0.2 M 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.5M N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS,Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) diluted in MES buffer.Gels were then washed for 30min with cold 60%methanol diluted in PBS(1st Base,Singapore),prior to overnight incubation with 50μg/mL fibronectin and 10μg/mL type I collagen in 0.5M HEPES buffer(pH 9.0,Sigma-Aldrich)at 4°C.0.5M ethanolamine (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in HEPES buffer was then added to the gels for 30min at 4°C before gels were washed twice with HEPES buffer and twice with PBS.The gels are sterilized with UV light in a sterile hood for 15min prior to seeding the neutrophils isolated from the mouse models.

2.4.Microscopy

Characterization of the neutrophil cell migration speed and cell traction stresses were performed 2h after seeding neutrophils into the polyacrylamide substrates.Differential interference contrast(DIC)images of the neutrophils and the fluorescent images of the GFP-expressing neutrophils and the red fluorescent beads embedded within the polyacrylamide gels were acquired on a FV1000 Olympus confocal microscope with 100× objective,zoom 2.5×, heated with objective heater.The system was allowed to equilibrate for 2h prior to imaging.Images with zstacks of 0.7μm thickness,were acquired every 3min for 15min for basal condition,following which 10nM CXCL12 was added to the chamber and imaged for 30min for CXCL12 stimulated condition.At the end of imaging, chambers were flushed with 0.125%Trypsin/Versene,pH 7.0 to detach cells and the chamber was imaged again to obtain the positions of the fluorescent beads in the unstressed polyacrylamide gels.

2.5.Traction stress calculation

The 2-dimensional traction stress calculation algorithm has been described previously.14Neutrophils were seeded on 6.2 kPa polyacrylamide substrates with pre-embedded 0.2μm diameter red fluorescent beads as described above.As the cell attached and exerted stresses on the polyacrylamide substrates, the substrates deform.Substrate deformations due to cell traction stress can be calculated by comparing images of the fluorescent beads embedded in the substrate before and after the neutrophils are detached by trypsinization.The substrate displacement fields were obtained using the digital image correlation method and the traction stress fields were subsequently calculated from the solution to the inverse Boussinesq problem as detailed in.14

2.6.Cell speed measurements

GFP-expressing neutrophils were segmented based on simple thresholding of GFP intensity in ImageJ to obtain cell outlines.The centroid of the cell was obtained and the centroid position is recorded over a time period of 30min after the addition of 10nM CXCL12 to the chamber.The net displacement of the cell is defined as the distance between the cell's position at t=0min and t=30min.The distance travelled between each time point is summed to obtain the cell's total distance travelled in 30min.An instantaneous cell speed at every time step (3min) was also computed.Basal cell speed v0of WT and WHIM neutrophils were calculated as average cell speed 15min prior to addition of CXCL12.The instantaneous cell speed of the neutrophils over time, post-CXCL12 stimulation, was fitted to a two-term exponential model (Equation (10)) using MATLAB.

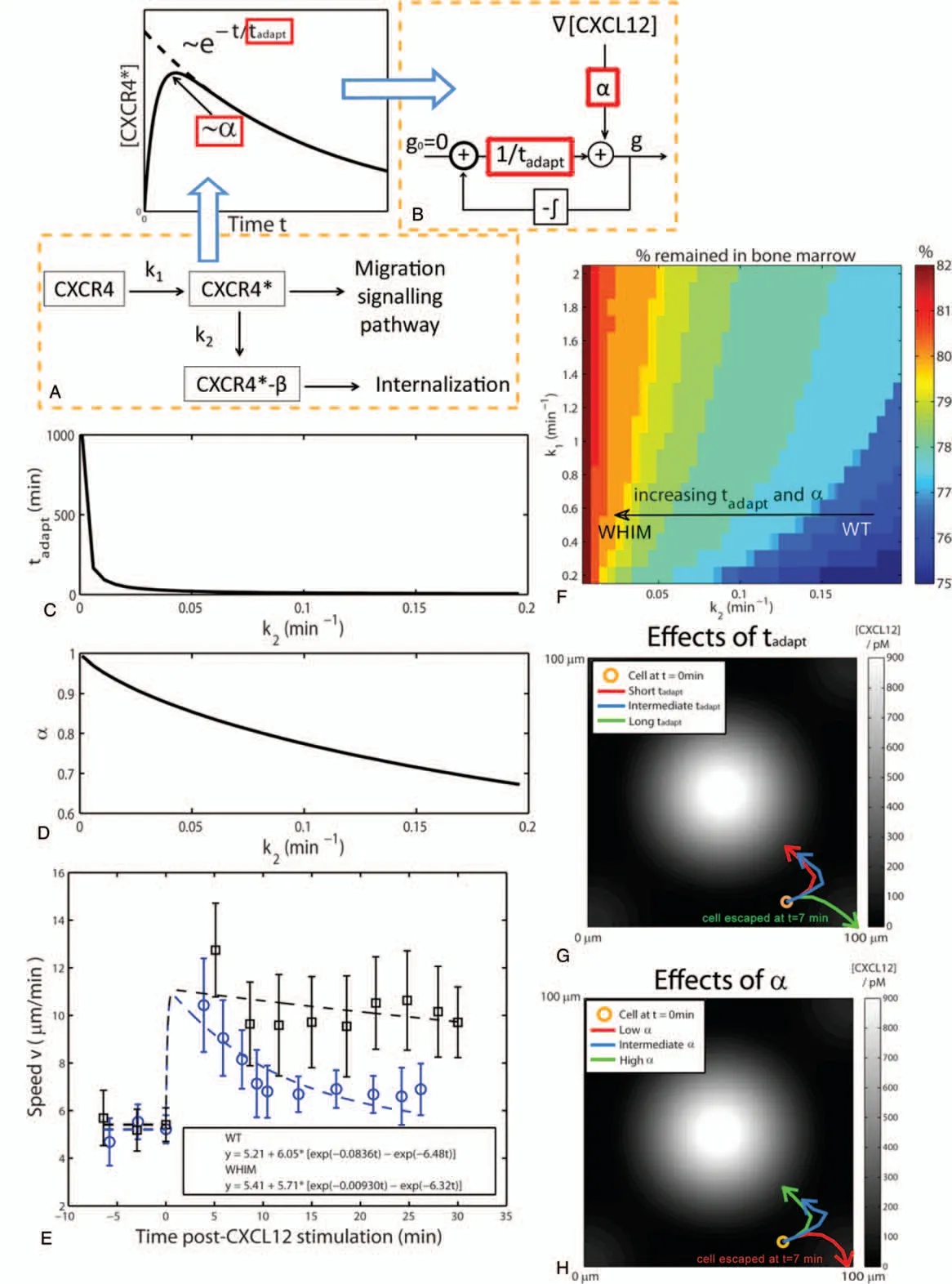

2.7.Desensitization model

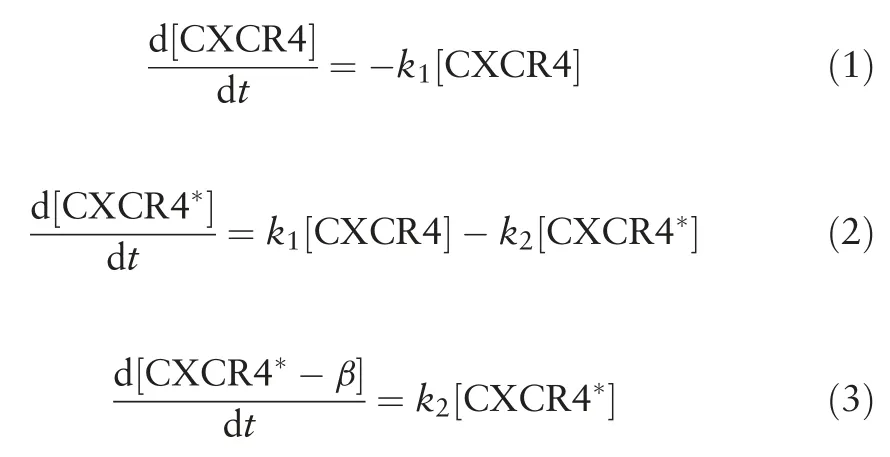

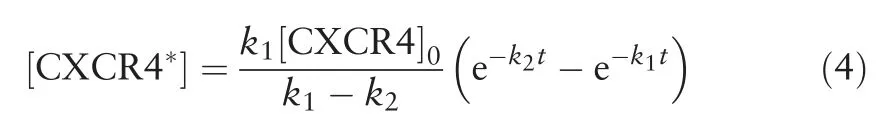

We have proposed a kinetic model of the CXCR4-CXCL12 interaction incorporating β-arrestin-mediated receptor internalization as shown in Fig.4A, to investigate how reduced CXCR4 internalization and desensitization to CXCL12 stimulation can alter CXCR4 sensitivity and CXCR4 internalization adaptation time of cells carrying the WHIM mutation.In the model,inactive unbound CXCR4 binds to CXCL12 with rate constant k1to form activated CXCR4(CXCR4*)which is assumed to further activate downstream signaling pathways involved in cell migration.CXCR4*also binds to β-arrestin with rate constant k2,assuming β-arrestin is present in excess,to form CXCR4*-β which activate endocytotic mechanisms to bring about CXCR4*-β internalization.The mass action kinetic equations governing the concentration of the respective molecules are given by Equations(1-3).

By solving the kinetic equations (1-3), the concentration of CXCR4*responsible for the migratory response of the cell can be written as follow:

We assume that the rate of internalization of CXCR4*is slower than the rate of formation of CXCR4*, i.e.k1>k2as CXCR4*receptor internalization requires activation of several other downstream kinases such as the G-protein coupled receptor kinasesprior toβ-arrestinassociation.1Therefore,atlarge t,k2will govern how fast[CXCR4*]decrease with time.We,thus,defined the CXCR4 internalization adaptation time(tadapt),to be 1/k2(Eq.(5)).Inaddition,wedefinedtheCXCR4sensitivitytoCXCL12(α),to be the maximum value of[CXCR4*],normalized by the initial CXCR4 concentration,[CXCR4]0and is given by Eq.(6).

2.8.Cell migration model

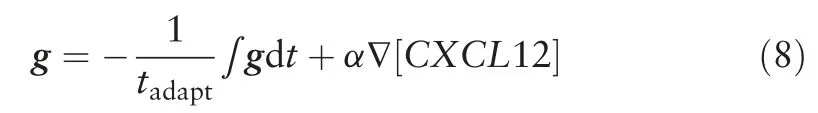

A cell migration computational model similar to the model proposed by Campa et al15was used to investigate the effects on neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow when cell sensitivity α and adaptation time tadaptto CXCL12 stimulation was varied.The bone marrow stroma is assumed to be a domain of the size 100×100μm.Initially, 200 cells were randomly positioned in the bone marrow stroma and the position vector r of each cell is updated based on equations(7-9).Cells are assumed to migrate at a constant basal speed of v0=5μm/min and the cell position vector r was changed over time according to the direction of the perceived CXCL12 chemokine concentration gradient g as shown in Eq.(7-9).

Chemokine (CXCL12) secreting stroma cells are assumed to localize at the centre of the simulation domain, which diffuses outwards,hence setting up a Gaussian CXCL12 chemokine field with standard deviation of 30μm and a maximum CXCL12 concentration of 1nM15in the middle of the domain(Fig.4G and H).The perceived CXCL12 concentration gradient g is represented by Eq.(8).

Particularly, the perceived CXCL12 gradient g takes into account the CXCR4 internalization adaptation time tadaptand CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 stimulation α,as well as the local CXCL12 concentration gradient, ∇[CXCL12].Values of tadaptand α were changed according to k1and k2as given by Eqs.(5)and (6).The relationships between g, tadapt, α and CXCL12 concentration gradient was represented by a simple negative integral feedback control system shown in Fig.4B.The negative integral feedback control system ensured that at steady state, in the absence of any perturbation to the system, the perceived CXCL12 gradient g will approach to the basal value of 0.Perturbation in the system occurs when the cell randomly migrates to a new region where it senses a difference in local CXCL12 concentration gradient around the cell.The change in the local CXCL12 concentration gradient is sensed by the cell,amplified by α and fed into the control system, resulting in a deviation of g away from its desired value of 0.The deviation of g from its desired value is measured as an error signal and signalled to the controller (in this case β-arrestin mediated receptor endocytosis)which produces the control signal that is a product of 1/tadaptand the integral of the error signal.Equation(8)can be rewritten in the form of Eq.(9)and Eqs.(7)and(9)were solved numerically by the forward Euler method.

After 500min, the number of cells that still remained in the bone marrow stroma was counted and a percentage of cell remaining in the bone marrow was obtained.

2.8.1.Statistical analysis.Student's 2-tailed t test with

unequal variance was performed in Excel.Two datasets are considered to be significantly different if the following P-values were obtained: P<.05 (*), P<.01 (**), P<.005 (***), or P<.001 (****).

3.RESULTS

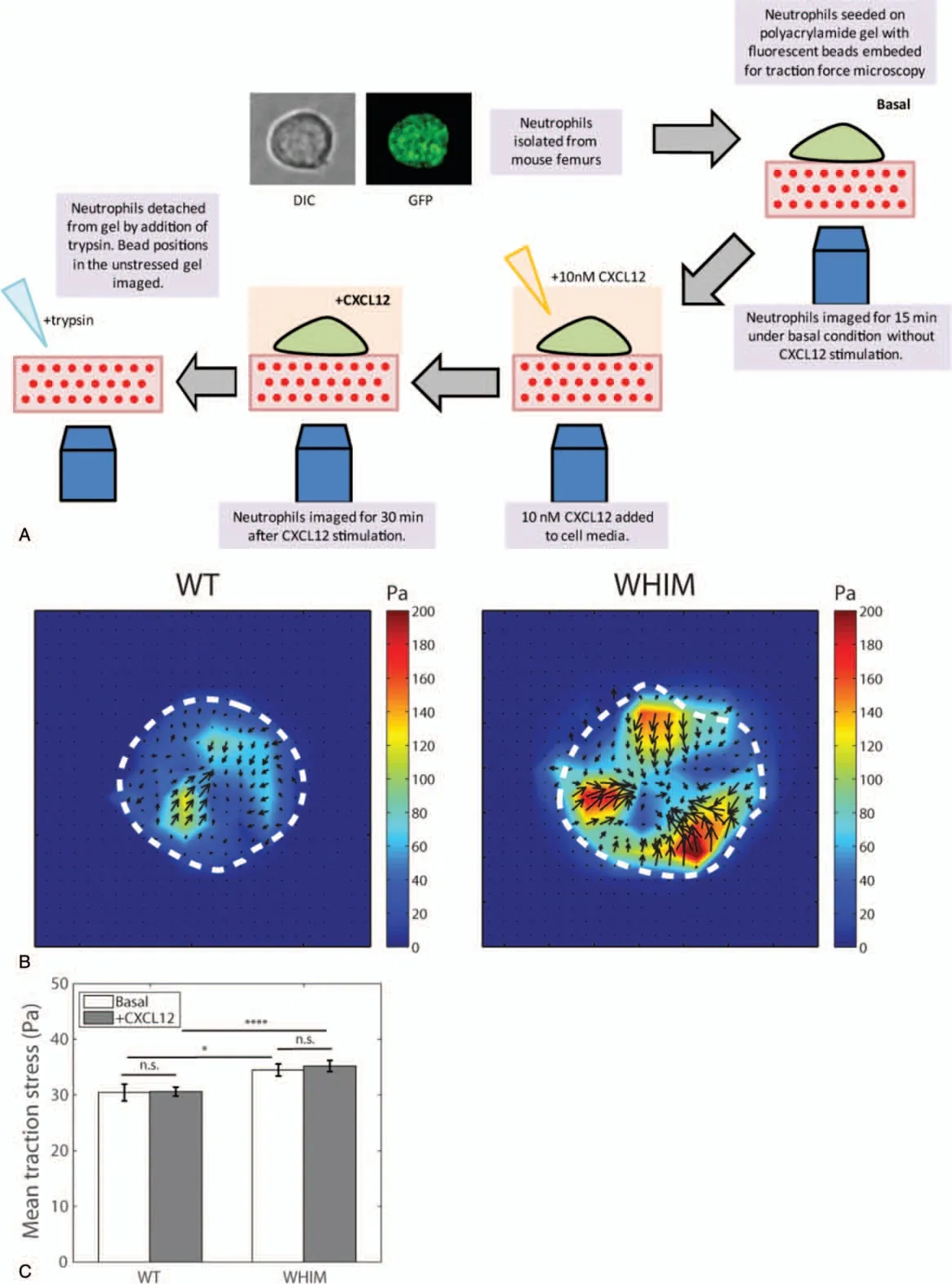

3.1.WHIM neutrophils exert larger traction stresses on their substratum compared to WT cells

WHIM leukocytes have been shown to display increased chemotaxis toward CXCL12 in transwell migration assays as compared to WT leukocytes,10,16however, the comparative forces they exert during migration and plausible role in bone marrow accumulation has not been characterized.In order to measure cell-exerted traction stresses during migration, 2-dimensional traction force microscopy was used.14,17Cells were seeded on soft elastic polyacrylamide substrates with Young's modulus of 6.2 kPa,the typical rigidity of bone marrow stroma18(Fig.1A).Polyacrylamide substrates were embedded with fluorescent beads and coated with both fibronectin and collagen to allow cell-substrate adhesion.As cells adhere and pull on the polyacrylamide substrate during cell migration,the deformation on the surface of the substrates can be measured by the displacements of the embedded beads.Measurement of the bead displacements is used to calculate substrate strains and traction stresses due to the cell-applied forces.Traction forces exerted by cells was measured before (basal) and after addition of 10nM CXCL12 (chemokine concentration used was based on peak response in chemotaxis and functional assays,unpublished data).

Average traction stress magnitudes exerted by WHIM neutrophils (basal: 34.2±7.25Pa; +CXCL12: 35.2±0.910Pa),before and after CXCL12 stimulation, were statistically higher(P-value=.0325 and .000453 respectively) than that exerted by WT neutrophils (basal: 31.9±11.2Pa; +CXCL12: 30.6±0.801 Pa)(Fig.1B and C).This suggests stronger cell-substrate adhesion in WHIM cells as compared to WT cells regardless of CXCL12 stimulation.The stronger cell-substrate adhesion may prevent cell detachment from the bone marrow stroma,thereby providing a possible mechanism for neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow in the WHIM mice.

3.2.WHIM neutrophils exhibit more lamellipodia protrusions upon CXCL12 stimulation

Stronger traction stresses are also generally correlated with increased cell migration speed.19In our experiments, we also observed from the DIC images that WHIM and WT neutrophils displayed distinct cell migration morphologies in response to CXCL-12 stimulation.To this end, cellular protrusions were categorized based on the aspect ratio (length/width) of the protrusions as either finger-like protrusions known as filopodia(aspect ratio >1), sheet-like protrusions known as lamellipodia(aspect ratio <1), or no protrusions for each cell at each time point (3min intervals) (Fig.2A).This approach of classification has also been used in other papers.20,21Subsequently, the percentage of the total time each cell appeared in a specific morphological phenotype was quantified.

Prior to CXCL12 stimulation, WT and WHIM cells did not form any protrusions about 50%of the time,although some cells occasionally formed filopodia-type (22% and 23% for WT and WHIM cells, respectively) or lamellipodia-type protrusions(approximately 27% for both WT and WHIM cells) (Fig.2B and C).Upon CXCL12 stimulation,WT and WHIM cells formed more protrusions thereby decreasing the percentage of time with no protrusions.In particular, WHIM cells show a statistically significant decrease in the percentage of time with no cell protrusion (from 51% to 5.7%, P-value=.000451), which correspond to a statistically significant increase in lamellipodiatype protrusions(55.9%)(P-value=.0157)and a slight increase in filopodia-type protrusions (38.5%) as compared to the basal state (27.3% and 21.6%, respectively) after CXCL12 stimulation.Notably, the WT neutrophils produced significantly more filopodia-type protrusions but not lamellipodia protrusions upon CXCL12 stimulation(51.6%)as compared to basal state(23%)(P-value=.00630).

Filopodia and lamellipodia are typically formed as a cell migrates.Specifically, filopodia protrusions are associated with extracellular matrix sensing to identify targets for adhesion which may mature into larger adhesion structures (focal adhesions)upon lamellipodia advancement.22,23Lamellipodia,on the other hand, are associated with efficient cell migration.24Fibroblasts which are devoid of lamellipodia through deletion of Rac1 gene,but not defective in filopodia formation, have been shown to migrate with lower speeds compared to wildtype cell that can form lamellipodia.24Hence,increased frequency of lamellipodiatype protrusions in WHIM neutrophils may result in increase in cell migration speed.In agreement, we found that cells forming the lamellipodia-type of protrusions tend to migrate at a faster speed than cells forming the filopodia-type protrusions(Fig.2D).

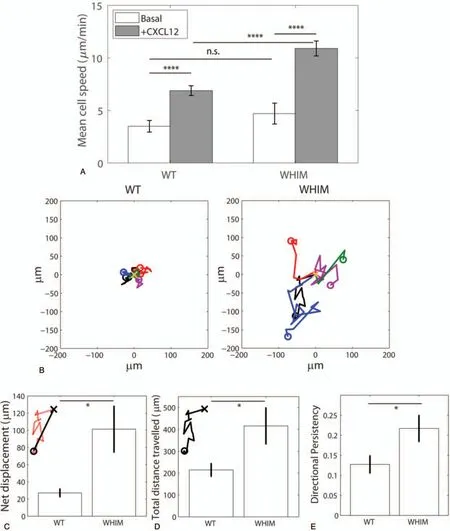

3.3.WHIM neutrophils exhibit increased migratory behavior

We then measured the mean instantaneous cell speeds of WHIM and WT neutrophils post-CXCL12 stimulation over a period of 30min, and observed that WHIM cells migrated at a significantly higher speed (10.9μm/min) than WT neutrophils(6.88μm/min)(Fig.3A,P-value=4.08e-6).Corresponding with higher migration speeds, WHIM neutrophils displaced further away from their original position compared to the WT neutrophils (Fig.3B) with higher net displacements (Fig.3C,101μm for WHIM, 27.1μm for WT, P-value=.0179) and exhibited larger travel distances after 30min as compared to WT neutrophils (Fig.3D, 416μm for WHIM vs 214μm for WT, P-value=.0364).WHIM neutrophils also exhibited higher directional persistency(Fig.3E)compared to WT cells(0.127 for WT vs 0.217 for WHIM, P-value=.0319).Track straightness or directional persistency of trajectory was calculated as ratio of net displacement to total distance traveled, with a value of 1 indicating a perfectly straight trajectory.Taken together, we noted general increase in cell migration properties are expected,given that WHIM neutrophils harbor gain of function mutation of the chemokine receptor.Despite increase in cellular migration,WHIM neutrophils tend to accumulate in the bone marrow.In order to understand the mechanism of how the mutation in WHIM neutrophils leads to bone marrow accumulation, we proposed a mechanochemical model for the chemotactic behavior of the neutrophils.

Figure 1.Traction stress measurements for WT and WHIM neutrophils.(A)Schematics illustrating experimental work flow.(B)Traction stress maps for WT(left)and WHIM(right)neutrophils post-CXCL12 stimulation.Dotted lines represent the cell boundaries.(C)Mean traction stress exerted by WT and WHIM neutrophils before(basal)and after CXCL12 stimulation(CXCL12)(n=20 for WT and WHIM).Error bars denote standard error of the mean.n.s.,*,and****represents not significant, P <.05, and P <.001respectively.

3.4.Increased cellular chemotaxis in WHIM neutrophils suggest higher sensitivity and longer CXCR4 internalization adaptation time in response to CXCL12

Cellular migration measurements suggest that WHIM neutrophils are primed for migration upon CXCL12 stimulation.WHIM neutrophils are known to be defective in receptor desensitization.1,5-8Inefficient CXCR4 internalization has been shown to prolong cellular responses such as pERK signaling and increase CXCL12-induced cell chemotaxis.10,16To better understand how defects in CXCR4 desensitization to CXCL12 stimulation may influence neutrophil activity in WHIM mutants,we first propose a simplified representation of the CXCR4-CXCL12 interaction,incorporating receptor internalization and desensitization as shown in Fig.4A.

Figure 2.Morphological characterization of WT and WHIM neutrophils.(A)DIC images of WT and WHIM neutrophils with no protrusions,filopodia-type protrusions(arrows),and lamellipodia-type protrusions(arrowheads)before and after CXCL12 stimulation.Scale bars denote 5 μm.(B and C)Percentage of time that each cell produce no protrusion,filopodia-type or lamellipodia-type protrusion as observed over 15 min period before CXCL12 stimulation and 30 min period post-CXCL12 stimulation for(B)WT(n=25)and(C)WHIM neutrophils(n=23).Error bars denote standard error of the mean.*,**,and****represents P <.05,P <.01,and P <.001,respectively.(D)Mean speed of WT(n=25)and WHIM(n=23)neutrophils exhibiting filopodia-or lamellipodia-type protrusion after CXCL12 stimulation.Error bars denote standard error of the mean.* represents P <.05.

Briefly, we assumed that unbound inactive CXCR4 binds to CXCL12 with rate constant k1, to form activated CXCR4(CXCR4*).CXCR4*activates downstream signaling pathways such as the phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases signaling, increased pERK levels eventually resulting in cell migration.1,6,9CXCR4*signaling is down-regulated by β-arrestin-mediated internalization pathways with rate constant k2.The mass-action kinetic equations governing the concentration of the reactants in the model are given by equations (1-3), assuming endogenous β-arrestin concentration remains approximately constant in the cell.By solving the kinetic equations(1-3),the concentration of CXCR4*responsible for the migratory response of the cell can be represented by Eq.(4).CXCR4 internalization adaptation time(tadapt), and the CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 (α), were also defined by Eqs.(5 and 6) as explained in Section 2.

Figure 3.Characterization of WT and WHIM neutrophils'migratory behavior.(A)Mean cell speed for WT and WHIM neutrophils under basal condition(Basal)and post-CXCL12 stimulation(+CXCL12).n=25(WT)and n=23(WHIM)(B)trajectories of 5 representative WT(left)and WHIM(right)neutrophils over 30 min post-CXCL12 stimulation.x denotes the starting point at t=0 min and o denotes the cell position after 30 min.(C)Mean net displacements of WT and WHIM neutrophils after 30 min post-CXCL12 stimulation.Inset shows the net displacement(solid line)of a cell's trajectory(dotted line).x denotes the starting point at t=0 min and o denotes the cell position after 30 min.(D)Mean total distance travelled over 30 min post-CXCL12 stimulation for WT and WHIM neutrophils.Inset shows the total distance travelled by the cell(solid line).x denotes the starting point at t=0 min and o denotes the cell position after 30 min.(E)Directional persistency(defined as average ratio of net displacement and total distance travelled over 30 min)of WT and WHIM neutrophils post-CXCL12 stimulation.Error bars denote standard error of the mean.n.s., *, and **** represents not significant, P <.05 and P <.001, respectively.

Figure 4.Mechanochemical model of neutrophil migration.(A) Schematic diagram of the signaling pathway involving CXCR4, CXCL12-activated CXCR4(CXCR4*),and CXCR4*bound to β-arrestin(CXCR4*-β).By solving the kinetic mass action equations for the reactants in the signaling pathway,the maximum[CXCR4*]value achieved,termed CXCR4 sensitivity α,and the time scale of the decay in[CXCR4*],termed CXCR4 internalization 5 adaptation time tadapt,can be written in terms of reaction rate parameters k1 and k2.(B)Schematic diagram of the negative integral feedback control system to obtain direction of the perceived gradient g based on values of the α and tadapt obtained from the reaction rate parameters k1 and k2.(C)Graph showing how tadapt change as k2 is varied.(D)Graph showing how α change as k2 is varied.(E)Cell speed vs time post-CXCL12 stimulation for WT(empty circles)and WHIM(solid squares)neutrophils.Dotted lines show the corresponding two exponential models fit to the experimental cell speed measurements.n=25 and n=23 for WT and WHIM,respectively.Error bars denote standard error of the mean.(F)Percentage of the cells in the bone marrow after 500 min in the computational model at various values of k1 and k2.(G)Trajectories,over 7 min,of a cell with a constant α=0.983,but different values of tadapt(short:tadapt=1.67 min;intermediate:tadapt=12.9 min;long:tadapt=167 min).(H)Trajectories,over 15 min,of a cell with a constant tadapt=167 min,but different values of α(low:α=0.465;intermediate:α=0.794 high:α=0.983).Concentration of CXCL12 is represented by the gray intensity, with increasing gray levels denoting increasing levels of [CXCL12].

From Eqs.(5)and(6),we observed that decreasing values of k2,as in the case of reduced CXCR4*internalization in WHIM mutant,will result in a longer tadapt,and higher α(Fig.4C and D).In order to verify that the WHIM cells indeed show longer tadapt,and higher α in their migratory behavior experimentally,instantaneous cell speed at every time point with respect to the time post-CXCL12 stimulation was computed.Prior to CXCL12 stimulation, mean basal cell speeds for both WT and WHIM neutrophils was similar (~5.2-5.4μm/min) (Fig.4E).After CXCL12 stimulation, cell speeds for both WT and WHIM neutrophils increased and gradually decreased as time progressed.The increase in cell speed,due to CXCL12 stimulation,was higher and decreased more gradually with time in WHIM neutrophils as compared to WT neutrophils.These observations suggest increased sensitivity of CXCR4 to CXCL12 and a longer adaptation time in WHIM neutrophils as compared to WT neutrophils.

We can also obtain an estimate for k1and k2experimentally by fitting the experimental speed measurement in Fig.4E to a twoterm exponential model in the form of Eq.(10)where a,b and c are fitted parameters.We assumed initial cell speed immediately before CXCL12 stimulation to be the mean basal cell speed v0and the fitted values of b and c were obtained as estimate values of k1and k2.

For WT neutrophils, estimates of k1and k2are 6.48 and 0.0836 min-1, respectively and values of k1and k2for WHIM neutrophils were 6.32 and 0.00930 min-1, respectively.These results verified that the rate of internalization of CXCR4*,k2for WT neutrophils is significantly higher than for WHIM neutrophils(~9 times higher),while the rate of CXCL12 binding to CXCR4, k1, for WT and WHIM neutrophils are similar, in agreement with published literatures.5-8

3.5.Mechanochemical model to explain WHIM neutrophil accumulation in bone marrow

We then seek to understand how changes in k1and k2can increase WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow.Although our results showed that WHIM neutrophils migrate faster and adapts slower to CXCL12 stimulation than WT cells,it is unclear why the WHIM neutrophils remain within the bone marrow and not migrate out into the blood stream.We proposed a mechanochemical model for neutrophil chemotaxis similar to the model proposed by Campa et al.15The bone marrow stroma is assumed to be a domain of the size 100×100μm and if cells moved out of this domain, they will be considered to have egressed into the blood stream.Cells are assumed to migrate at a constant basal speed of v0=5μm/min and the cell position vector r was changed over time according to the direction of the perceived CXCL12 chemokine concentration gradient g as represented by equations (7-9)

By sweeping through a range of values for k1and k2, we observed that the percentage of neutrophils remaining in the bone marrow after 500min increased as k2decreased (tadaptand α increased), and increased as k1(α increased) (Fig.4F).Particularly, we focus on the effects of changing k2since experimental observations revealed that the change in k2is more significant as compared to the change in k1between WT and WHIM cells.When k2decreased,as in the case of WHIM mutant,both tadaptand α increased according to Eqs.(5)and(6).We therefore tried to understand the individual contributions of tadaptand α on neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow by varying modelled values of tadaptand α independently.

For increasing values of tadapt,at constant α,neutrophil retain memory of the CXCL12 concentration gradient encountered previously for a longer time,displaying persistent motility.They are therefore slow to change migration direction determined by local CXCL12 concentration(Fig.4G,green line).On the other hand, when tadaptis short, the neutrophil adapts efficiently to local CLCL12 gradients migration direction according to the chemokine gradient it experience at each time point(Fig.4G,blue and red line).

For low values of α,at constant tadaptneutrophil is insensitive to the low CXCL12 concentration gradient at regions away from bone marrow stroma niches and fail to migrate toward the direction of increasing CXCL12 concentration thereby increasing egression probability from the bone marrow stroma(Fig.4H,red line).When α is increased,neutrophil becomes more sensitive to the CXCL12 concentration gradient experienced and its migratory direction is increasingly directed toward the source of CXCL12 production(Fig.4H,blue and green line)resulting in subsequent accumulation in the bone marrow.Overall, our mechanochemical model proposes that bone marrow accumulation of WHIM neutrophils is a function of low values of CXCR4*internalization rate (k2) leading to increased tadaptand α which collectively contribute to increase WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow as compared to WT neutrophils.

4.DISCUSSIONS

WHIM syndrome is an inherited primary immunodeficiency disease that subject the affected individual to recurrent bacterial infections due to low counts of most leukocytes, including neutrophils, circulating in the blood.1,5,9CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling axis is an important regulator of blood neutrophil numbers.CXCL12 expressed by stroma cells in bone marrow is important for neutrophil accumulation and homing to the bone marrow.WHIM patients expressing truncated CXCR4 display active receptor signaling that decays over a longer time as compared to WT leukocytes upon ligand stimulation.It has been shown that CXCL12-activated WHIM leukocytes show sustained activation of downstream signaling pathways such as pERK with greater signaling amplitude.10Mutant leukocytes also exhibit higher sensitivity to CXCL12 as a larger percentage of cells chemotaxed toward CXCL12 in transwell assays compared to WT cells.10,16

Mechanochemical properties of WHIM neutrophils have been poorly studied both in vitro and in mice.We set out to characterize behavior of these mutant leukocytes using traction force microscopy.Interestingly, we observed that WHIM neutrophils are more adherent to the substrate as compared to WT cells.It has also been shown that CXCL12 binding to CXCR4 activates Rap1, a small guanosine triphosphatases(GTPase) responsible for increased lymphocyte adhesion to intercellular adhesion molecule-1.25Given that WHIM neutrophils accumulate in the bone marrow and fail to egress efficiently into circulation during infection, increased cell-substrate adhesion between the WHIM neutrophils and their underlying substrates can contribute to increased neutrophil accumulation within the bone marrow.Indeed, neutrophils can be mobilized into the blood circulation in mice by treatment with a α4-integrin antibody,which reduces neutrophil adhesion to an extracellular ligand known as vascular cell adhesion protein.26

In addition to exhibiting increased adhesion, CXCL12 stimulated WHIM neutrophils formed more sheet-like, lamellipodia-type cell protrusions while WT neutrophils formed more finger-like, filopodia-type protrusions, suggesting differences in sensory and or migratory behavior of the cells.Filopodia are typically associated with gradient sensing and cell polarization while lamellipodia is associated with cell locomotion and migration speed.27,28We also observed that cells, which form lamellipodia-type protrusions tend to migrate at a faster speed than cells which form filopodia-type protrusions.The increased frequency of lamellipodia-type protrusions in WHIM neutrophils therefore corresponds to an increase migration speed of the WHIM neutrophils observed in the in vitro assays.In addition,the type of protrusions formed by the WT and WHIM cells also suggest differences in actin dynamics induced by CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling in the WT and WHIM cells.Particularly,different members of the ras-related superfamily of small GTPases are implicated in the formation of lamellipodia and filopodia.Lamellipodia protrusions are associated with the small GTPase,Rac1/2,which up-regulates actin-related protein 2/3 and induces F-actin branching network in the lamellipodia protrusions.On the other hand,filopodia formation is associated with the small GTPase Cdc42, that activates formins and induce F-actin bundling in the filopodia protrusions.29,30Further work to quantify and validate the difference in the activities of the respective small GTPases in WT and WHIM neutrophils may potentially elucidate novel targets for reversing WHIM neutrophil aberrant accumulation in the bone marrow.Increased lamellipodia protrusions potentially allow WHIM neutrophils to migrate faster, with increased net displacements and persistent motion, due to increased sensitivity to CXCL12.The classification of lamellipodia-type or filopodia-type protrusions may also be further quantified through immunofluorescence staining of F-actin or markers for lamellipodia(e.g.,cortactin and WAVE)and filopodia (e.g., Fascin and VASP).31,32However, as the cellular protrusions are formed dynamically,with the same cell possibly forming filopodia at one instance and lamellipodia at another instance, immunofluorescence staining may not be able to provide accurate dynamic information about the types of protrusion formed over time.In addition, as the neutrophils used in the manuscript are primary cells obtained directly from the bone marrow of mice,it is not possible to transfect the cells to express fluorescent markers of lamellipodia or filopodia.We are therefore restricted to only visual inspection of the morphology of protrusions formed by neutrophils for classifying lamellipodia or filopodia.

Increased sensitivity of CXCR4 to CXCL12 stimulation is primarily associated with lack of CXCR4 internalization post-CXCL12 stimulation.5It is known that in cells carrying the WHIM mutation, β-arrestin-mediated CXCR4 internalization and desensitization to stimulation is impaired due to the truncated C-tail of the receptor.We therefore sought to represent the interactions between CXCR4, CXCL12 and β-arrestin in a series of kinetic equations to show that the lower rate of β-arrestin mediated CXCR4 internalization k2, did indeed increase CXCR4 internalization adaptation time, tadapt.In addition, we also observed a higher maximum value of[CXCR4*], and hence higher CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 stimulation α, when k2, the rate of internalization, is lowered.

To understand how changes in CXCR4 internalization adaptation time and CXCR4 sensitivity can alter neutrophil egression, we have adapted a mechanochemical model for neutrophil chemotatic behavior from a previously published model proposed by Campa et al.15The original model by Campa et al was used to study neutrophil chemotaxis in the presence of two opposing chemotactic cues which activates or deactivates Rac signaling respectively,bringing about changes in Rac signal adaptation time and neutrophil egression time.In our manuscript, however, we have considered neutrophil chemotaxis as arising from the activation and internalization of the CXCR4 receptor in the presence of CXCL12 ligand.Thus, we have modified the model such that the adaptation time in the model represents the CXCR4 internalization adaptation time obtained from the mass kinetic equations(1-4)and as represented by Eq.(5).We were able to show that decreasing k2, which results in increased tadaptand α, can increase neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow as observed in WHIM mouse models.Experimental measurements of neutrophil migration speed in in vitro assays also verified that tadaptand α of WHIM neutrophils is increased through a reduction in the value of k2as compared to WT neutrophils.

Interestingly,our model predicted that changing k1,the rate of CXCL12 binding to CXCR4, would not alter tadapt, although decreasing k1did result in lower α as well as reduced neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow.This is similar to reducing neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow of WHIM patients with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100,also known as plerixafor.AMD3100 is clinically approved by US Food and Drug Administration used in hematopoietic stem cells mobilization from the bone marrow into the blood stream for stem cells collection from the blood during cancer treatment.33The drug is currently being tested as a potential treatment to rescue neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow in WHIM patients.34AMD3100 is a specific non-peptide CXCR4 antagonist that inhibits the binding of CXCL12 to CXCR4,35,36thus lowering k1.It has been shown that blood neutrophil and leukocyte counts increased after AMD3100 administration in both WT mice and mice carrying a WHIM mutation.13Future work to characterize the tadaptand α of WT and WHIM neutrophils'in the presence of AMD3100 can be done to verify our mechanochemical model.

In conclusion, we have shown that neutrophils derived from WHIM mouse model exhibit longer CXCR4 internalization adaptation time and increased CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 stimulation in in vitro cell migration assays, as compared to neutrophils derived from WT mice.To understand how increased CXCR4 internalization adaptation time and CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12 enhances WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow, we have proposed a mechanochemical model of the CXCR4-CXCL12 interaction, incorporating CXCR4 activation by CXCL12 and CXCR4 receptor internalization through β-arrestin-mediated endocytosis.The model explained how reducing the receptor internalization rate k2, as in the case in WHIM neutrophils,can result in longer CXCR4 internalization adaptation time and increased CXCR4 sensitivity to CXCL12.Through the model,we also explained that both longer CXCR4 internalization adaptation times and increased CXCR4 sensitivity, collectively contribute to the increased accumulation of WHIM neutrophils in the bone marrow.We have also propose,through traction stress measurements, that WHIM neutrophils are more adherent to the substratum which may contribute to the increased accumulation of WHIM neutrophils in the bone marrow.Lastly, differences in the type of cell protrusions produced by WT and WHIM neutrophils may suggest differences in the signaling pathways involved in the activation of the rasrelated superfamily of small GTPase(Rac and Cdc42).Although more work is necessary to elucidate the differences in cellsubstrate adhesions and small GTPase activation due to CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling in WT and WHIM neutrophils,our work has offered a mechanistic framework to understand WT and WHIM neutrophil migration and accumulation in the bone marrow.While the study has largely focused on the WHIM neutrophil accumulation in the bone marrow, the findings may also be extended to understand the effects of up-regulated CXCR4-CXCL12 signaling observed in cancer cells during tumour progression6http://links.lww.com/BS/A8.

杂志排行

血液科学的其它文章

- Successful ex vivo expansion of mouse hematopoietic stem cells

- Cell cycle regulation and hematologic malignancies

- Will immune therapy cure acute myeloid leukemia?

- Engineered human pluripotent stem cell-derived natural killer cells: the next frontier for cancer immunotherapy

- Hematopoietic stem cell metabolism and stemness

- Epigenetic regulation of hematopoietic stem cell homeostasis