Permanent Revolution

2019-09-10孙佳慧

孙佳慧

The hair-raising history of cuts and curls in

In 1955, when Chinese gymnast Lu Enchun took part in a competition in Warsaw, he was angered by locals who gawked at the back of his head to see if he still wore a “queue.”

Thus, in 1957, before competing in the International Friendly Sports Games of Youth in Moscow, Lu decided to try something drastic: getting a perm. At a cost of 8 RMB, this was a luxury at the time; even Lu, then captain of China’s national men’s gymnastics team, earned just 88 RMB per month.

Still, Lu recalls today to editors of Xinhua News Agency’s , he felt the expenditure was necessary in order to display Chinese athletes’ “spiritual outlook” to the outside world, and show that “Chinese people no longer had bound feet or pigtails.”

Lu chose to take his bold hair experiment to Beijing’s Silian Hairdressing Shop, a famous establishment founded by a merger of four well-known Shanghai hair salons, all of which moved to Beijing in 1956 in response to the central government’s call to modernize the capital’s service industry. According to , Deng Xiaoping even sent a Soviet hairdressing manual to one stylist at Silian, telling him, “Making Chinese female comrades beautiful is an honorable mission.”

In China’s resource-strapped 50s, though, perms had less resemblance to a beauty procedure than to medieval torture. “They took out a pair of fire-tongs, heated them red in the stove, and curled the hair…It smoked, and I smelled hair burning,” Lu recalls, adding that he was quaking in his chair with fright, and had to remind himself that his stylists were reputed to be the most advanced in China at that time.

Perms were rare in Lu’s day, especially for men—but then, so were most other exploratory hairstyles. Ever since the imperial Qing dynasty was overthrown in 1911, and Chinese men cut off the mandatory braids enforced by their Manchu rulers, the nation had been struggling to find a signature coiffure. In the early days of the Republic of China, many men followed British side-parting or slicked-back styles in an attempt to modernize their look. After the founding of the PRC, blue-collar men tended to go for buzz cuts or crew cuts, which were easy to keep clean and out of the way during manual work. Intellectuals often kept a center-parted or slicked-back style.

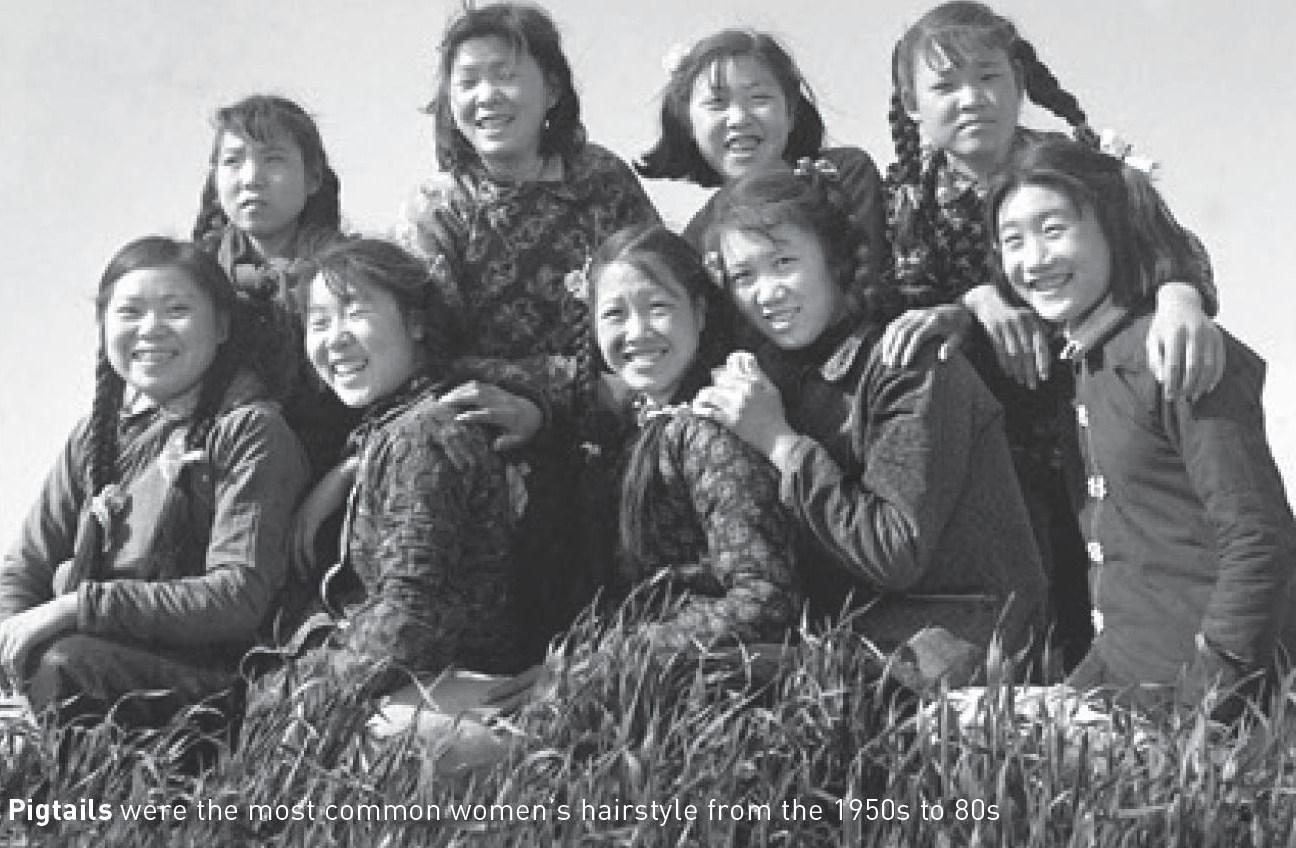

Women didn’t have many choices of hairstyles, either. Most wore pigtails or bobbed hair—which was called the “Liu Hulan Style” for its resemblance to that of a well-known revolutionary martyr in the 1930s. “[In the common view,] before the founding of the PRC, only rich ladies or dance hostesses had their hair permed,” says Lu.

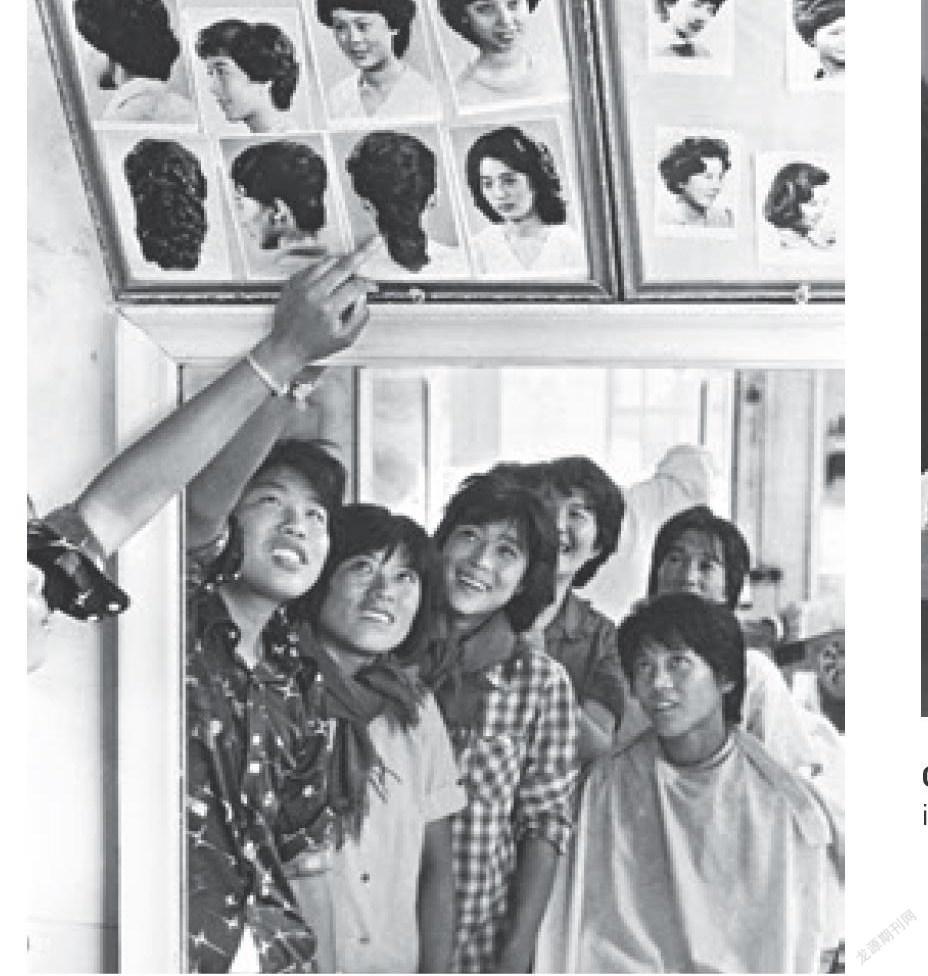

It was only after the reform period that permanent waves became a nationwide fad. All of a sudden, everyone wanted curls. In 1982, Shanghai’s biggest salon, the Nanjing Hairdressing Shop, had an average of 250 customers seeking a perm every day. Their busiest day saw more than 400 customers. Even in Ligezhuang Township, Shandong province, there were over 10,000 perms in 1984, whereas only five people in the entire rural community had sported perms just three years earlier.

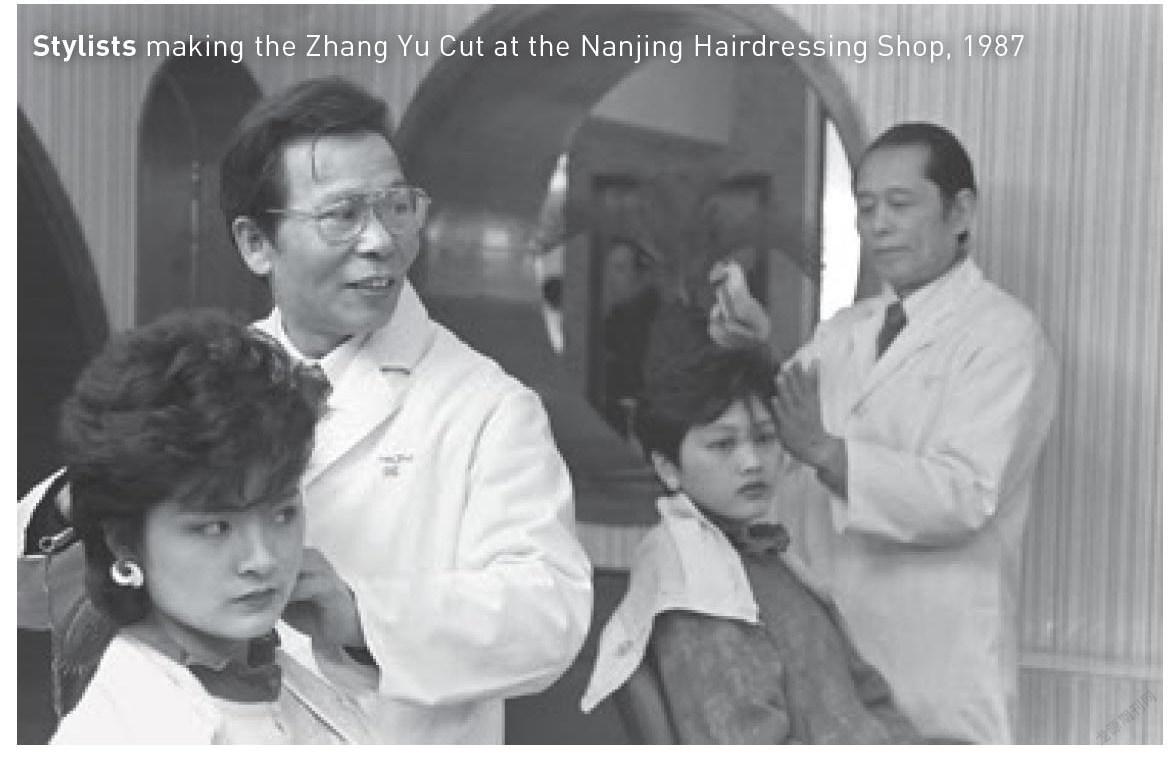

Amid the dizzying wave of consumerism that came with market reforms, permed hair was quickly joined by other available choices. To keep up with trends, many people imitated the hairstyles of movie stars. In the 1980s, a bob known as the “Yamaguchi Momoe Cut” was popularized among Chinese women by the Japanese actress of the same name. Chinese actress Zhang Yu’s short perm in the 1981 movie was also much imitated, and sent hairdressers across the country to Shanghai to learn to replicate it. Thanks to the “Zhang Yu Cut,” the Nanjing Hairdressing Shop was able to make up within one year the 200,000 RMB operational deficit it had accumulated over the past eight years.

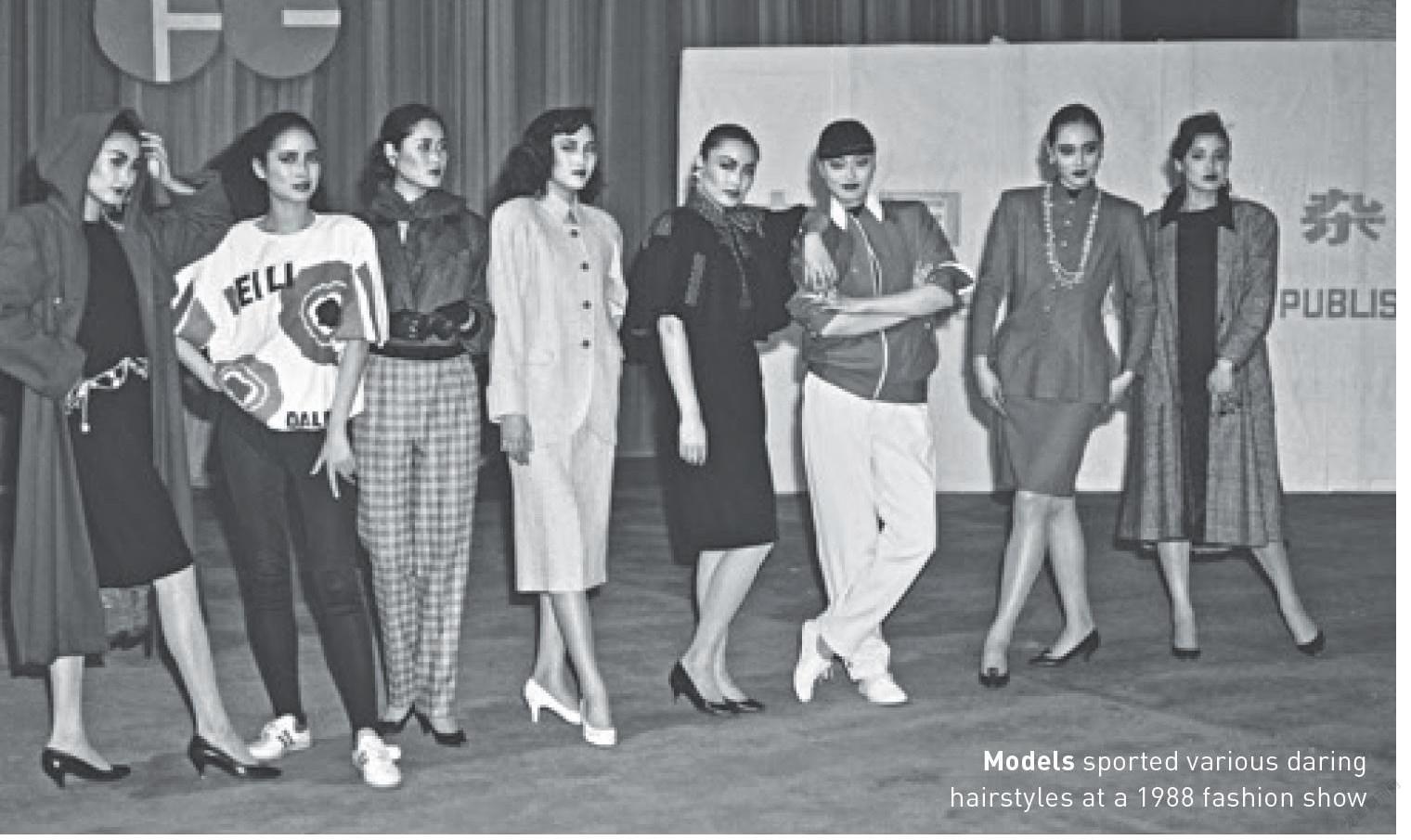

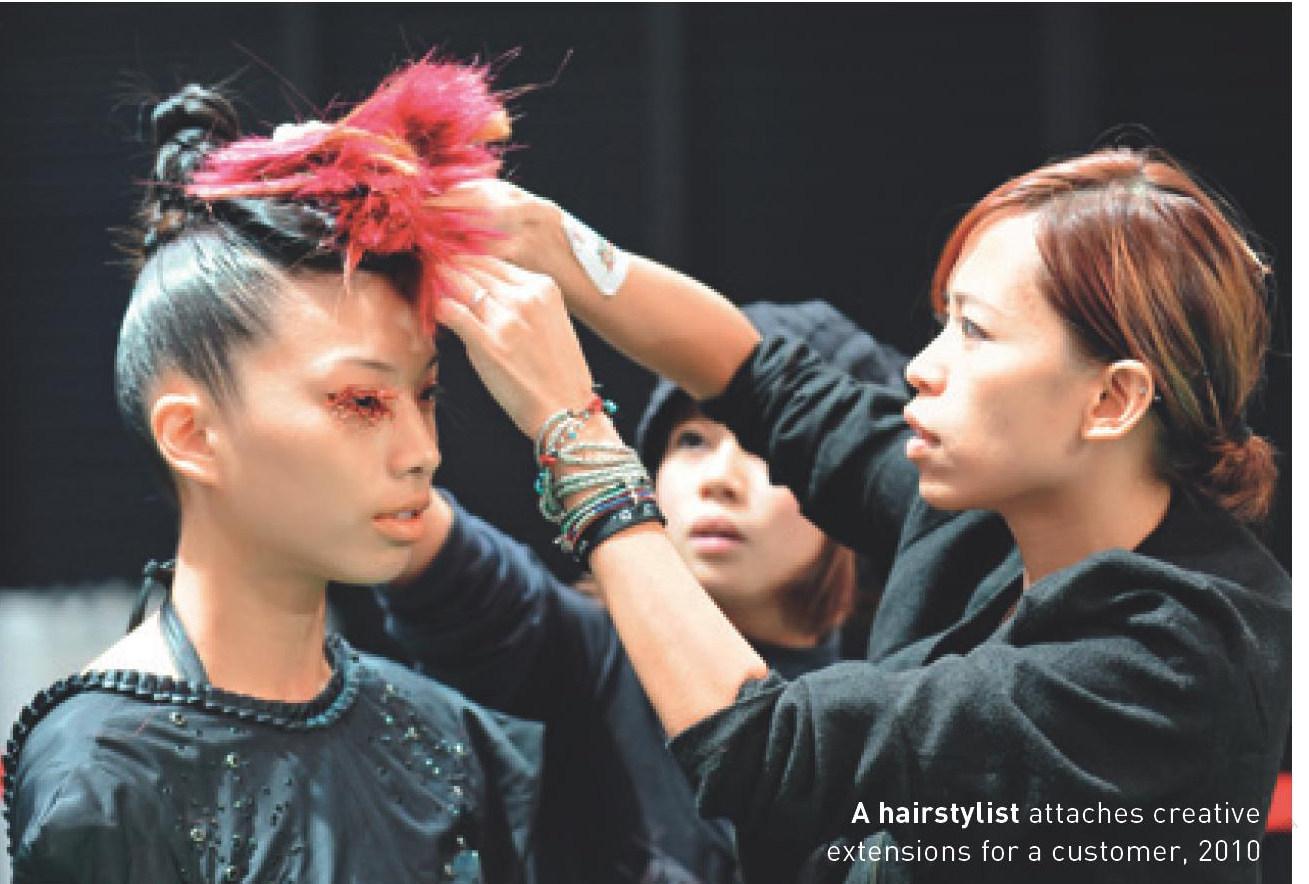

Today, it’s no longer possible for a single style to rule a generation. From the punk-inspired “Shamate” style of the early 2000s, to the complex dreadlocks popularized by hip hop, hairdressing choices are increasingly seen as matters of individual expression. Compared to the start of the reform period, when there were only about 10,000 hair salons in the country, the number has increased to 180,000 as of 2016, according to , and Chinese people spend more than 130 billion RMB on their hair every year.

Not everyone, though, enjoys “freedom of hairdressing”: This August, a Xiamen secondary school asked an incoming freshman for a hospital note to prove that her curly hair is natural, due to their “no dyeing or perming” policy. Earlier in the year, a Guangzhou middle school required all its students to wear short hair, dividing public opinion between those who decried this stifling of individualism and those who applauded the effort to keep distractions out of the classroom. Whether at the founding of a nation or throughout its liberalization, as writer Li Gaolei puts it, “People’s pursuit of varied hairstyles reflects their constant desire and visions for a beautiful life.”