Evolution of the prostate cancer genome towards resistance

2019-08-01FrancescaLorenzinFrancescaDemichelis

Francesca Lorenzin, Francesca Demichelis,2

1Department of Cellular, Computational and Integrative Biology, University of Trento, Trento 38123, Italy.

2Englander Institute for Precision Medicine, New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY 10065, USA.

Abstract

Keywords: Prostate cancer, cancer evolution, resistance mechanisms, androgen receptor, metastases, castration resistant prostate cancer, genomics, epigenetics

INTRODUCTION

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy diagnosed among men in the US and is a major cause of death with 164,690 new estimated cases in 2018 and 29,430 expected deaths[1].PCa is a clinically and genetically heterogeneous disease.Although the 5-year relative survival rate of patients diagnosed with localized disease is higher than 99%, a minority of patients progress to an aggressive form with metastasis spreading and high mortality[1].

At disease initiation, PCa relies on the androgen receptor (AR) signaling pathway for growth.Hence, the mainstay of therapy for PCa is represented by androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) as initially described by landmark work of Charles Huggins and colleagues in 1941[2,3].At recurrence upon prostatectomy or radiotherapy, ADT usually involves ablation of androgen synthesis through chemical castration by administration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists and the use of competitive androgen receptor antagonists to further impede AR signaling.Despite this fi rst-line therapy, most PCas adapt to androgen deprivation and restore AR signaling in the setting of low androgen production, a state referred to as castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).The development of next-generation AR pathway inhibitors, such as abiraterone and enzalutamide[4-7], allowed for survival benefits to patients with CRPC thanks to their ability to inhibit de novo androgen synthesis or to bind to and inactivate AR itself,respectively.However, drug resistance ultimately emerges.

GENOMICS OF ADVANCED AND LOCALIZED DISEASE

The genomics of PCa has been more challenging to study with respect to other solid tumor types due to multiple reasons, including intra-patient tumor heterogeneity and prevalence of structural genomic changes[8].In the past ten years, technological advances in next generation sequencing fi nally facilitated the deep genomic and epigenomic characterization of hormone naïve and castration resistant disease.This led to a more refined definition of molecular subclasses that could ultimately be used by clinicians to adjust the therapeutic strategies when resistance emerges.Over the last decade, a plethora of studies based on tumor tissue analyses (from prostatectomies, tissue biopsies or rapid autopsy program samples) has been published.More recently, the development of genomic and molecular profiling of prospectively collected liquid biopsy samples from individual patients has improved the critical evaluation of ongoing therapies thanks to the timely detection of mutations that arise in the resistant tumors.

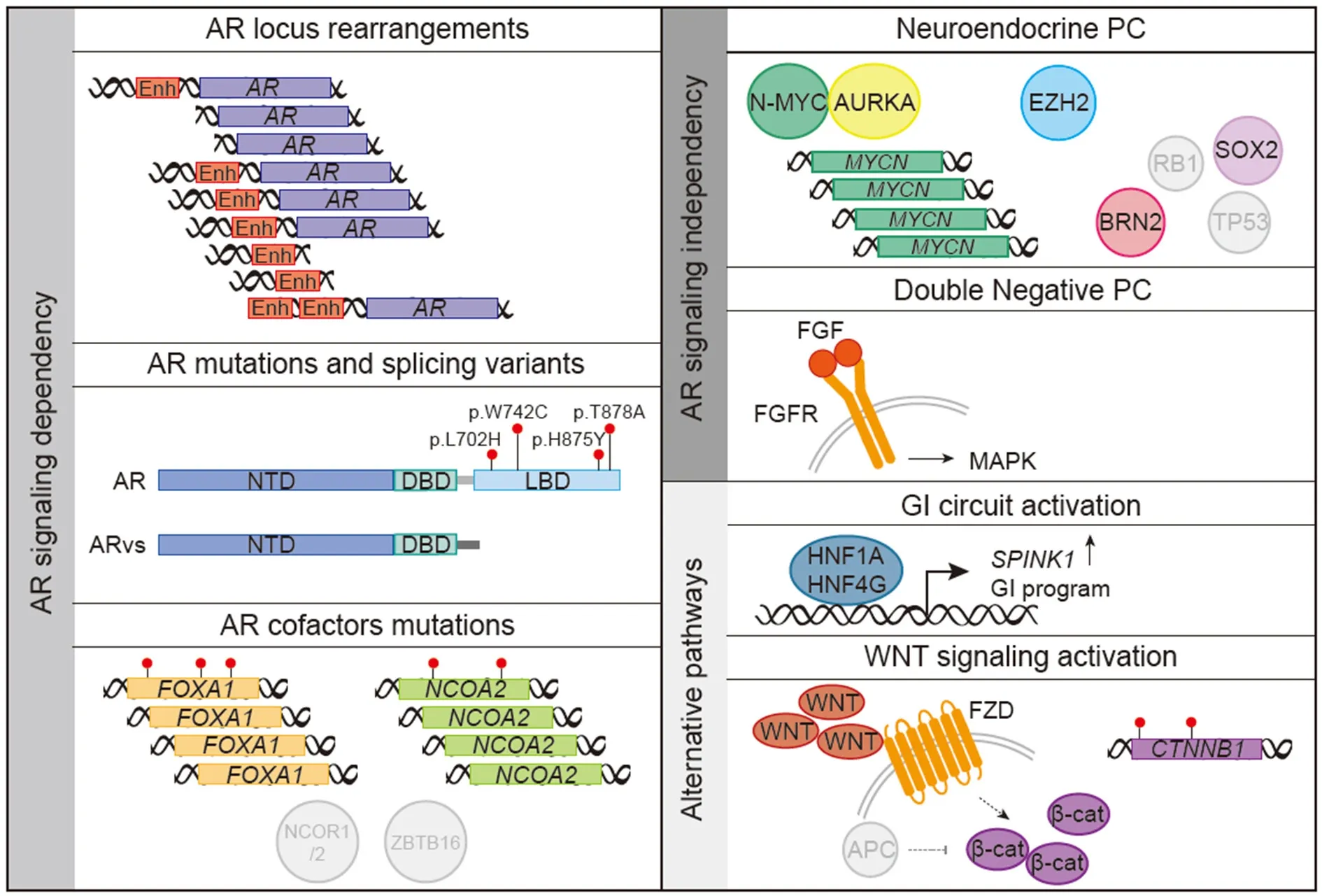

Primary prostate cancers are usually characterized by a diploid genome, low mutational burden, genomic rearrangements mainly involving the ETS genes and copy number aberrations, including deletions and amplifications.The overall genomic burden is associated with tumor grade[9-12]and with biochemical recurrence[13,14].Large and complex chromosomal rearrangements - such as chromoplexy and chromothripsis- are also prominent features of the prostate cancer genome[15-17].CRPCs are highly aneuploidic, with approximately 40% of tumors being triploid and with a higher mutational load[18-21].The comparison of the genomic status of primary prostate tumors and CRPCs identified lesions in TP53, AR, RB1, APC and BRCA2,among others, as enriched in the latter.These studies have shed light on the genomics driving prostate cancer resistance, which includes genomic rearrangements, point mutations and epigenetic changes[18,22-24].This review will focus on the main mechanisms driving resistance to ADT therapy in advanced tumors that is mainly achieved either by restoration of the AR signaling or by enhanced lineage plasticity and activation of alternative pathways, thereby sustaining tumor growth independently from AR[25].The review will emphasize relevant aspects related to genomic features and functional studies reported for each mechanism of resistance [Figure 1].

GENOMIC FEATURES OF AR-DEPENDENT RESISTANCE

Figure 1.Schematics of the main mechanisms linked to the development of resistance to androgen deprivation therapy and androgen receptor (AR)-targeted therapies in prostate cancer.Genomic rearrangements and mutations in the AR locus or its cofactors restore AR signaling promoting tumor growth.Alternatively, tumor cells transition towards an alternative AR-independent lineage showing neuroendocrine phenotype [neuroendocrine prostate cancer (NEPC)] in the setting of MYCN amplification and/or RB1 and TP53 loss.Tumors cells showing neither activation of the AR program nor neuroendocrine markers (DNPCs, double negative prostate cancer) show activation of the FGFR-MAPK pathway.Alternative pathways that promote tumor growth independently of AR include a gastrointestinal(GI) circuit controlled by specific master transcription factors and the WNT pathway.Enh: enhancer; NTD: N-terminal transactivation domain; DBD: DNA-binding domain; LBD: ligand-binding domain

AR is a nuclear hormone receptor that upon activation by androgens [testosterone and 5-alphadihydrotestosterone (DHT)] translocates into the nucleus and binds to specific regulatory regions [AR responsive elements (ARE); in promoters and enhancers], regulating specific target genes and promoting prostate cell proliferation and survival.Functional studies consistently demonstrated that the majority of CRPCs are still dependent on AR signaling.The mechanisms and mutations that sustain AR signaling even at low concentrations of androgens are multiple and mainly involve the AR gene itself.Early investigations led to the discovery of amplification of the AR locus as possible contribution of AR to progression towards CRPC.In 1995, Visakorpi et al.[26]reported its amplification in 30% of CRPC patients and in none of the patient-matched primary tumors before ADT[26].Since then, work from other groups focusing on the genomic characterization of advanced prostate tumors identified AR locus amplification and gain in > 50% of cases, the most prevalent aberrations linked to resistance to AR-targeted therapy[19,22,24,27,28].Copy number alterations of the AR locus were shown to be associated with increased expression of AR[29]and with progression to CRPC[30].Functional validation showed that higher levels of the receptor are indeed sufficient to promote the hormone-sensitive to hormonerefractory transition in castrated condition[31,32].Interestingly, whole genome sequencing studies revealed that the presence of structural rearrangements in regulatory elements controlling AR expression is associated with its increased levels and with castration resistance[18,33].Of note, copy number gain of a region upstream of the AR locus that is characterized by histone marks typically found in enhancers, can act independently of the AR locus amplification to increase AR expression levels in response to fi rst-line ADT[18,33,34].

AR point mutations are detected in 10%-20% of advanced prostate cancers upon development of treatment resistance but rarely before endocrine treatment[23,35,36].Although early studies using PCR-based methods identified mutations in the N-terminal transactivating domain of AR, the next generation sequencing technology-based characterization identified a mutational hot spot in the ligand-binding domain of the gene[19], including four most frequently observed missense mutations, L702H, W742C, H875Y and T878A.These retrospectively identified point mutations are rarely detected in primary tumors, indirectly suggesting the emergence of these mutations as mechanisms to drive resistance to the therapy[22].

Recent reports based on the analysis of cell free DNA from CRPC patient’s plasma associate AR aberrations(both amplification and mutations) with worse outcome and with resistance to abiraterone and/or enzalutamide.These observations highlight the possibility of using plasma-based AR status as biomarker for therapeutic management selection[37-40].

Studies leveraging liquid biopsy to obtain prospectively collected patients’ circulating tumor DNA also allowed for the evaluation of tumor clone dynamics and demonstrated the temporal association of AR point mutations with clinical progression.Emergence of AR-L702H mutation was observed in patients receiving exogenous glucocorticoid in combination with second generation AR antagonists (enzalutamide or abiraterone), whereas H875Y and T878A AR mutations were detected at progression on abiraterone and prednisolone[41].AR-L702H and T878A emerged at progression in patients treated with abiraterone[39].F877L and other mutations were identified in a small number of patients analyzing cell free DNA and were found in CRPC patients who had progressed while on ARN-509 or enzalutamide treatment[37,40,42].

In vitro characterization of AR mutants driving resistance to antiandrogens was fostered by the discovery of a mutated form of AR in the LNCaP cell line[43].Screening using a randomly mutagenized AR library in prostate cancer cell lines under the selective pressure of enzalutamide linked the emergence of AR mutations to the development of resistance[44].Mutations in the ligand-binding domain of AR resulted in gain-of-function by modulation of the ligand-binding affinity with increased sensitivity to other androgenic and nonandorgenic ligands, such as progesterone and glucocorticoid, which can remain at increased levels in patients treated with abiraterone[45,46], and conversion of direct antagonists into agonists (e.g.,bicalutamide, fl utamide).For instance, T878A and H875Y mutants are paradoxically activated by the antiandrogens nilutamide and fl utamide[43,47].In this setting, the anti-androgens behave as an agonist leading to the activation of AR target genes.AR L702H, but not wild type AR, is activated by prednisolone and this activation at glucocorticoid concentrations found in patients is not inhibited by enzalutamide[41].

Expression of AR splicing variants (AR-Vs) has emerged as an additional mechanism driving resistance to fi rst and second generation AR-targeted therapies.These alternative AR-Vs lack the C-terminal ligandbinding domain via truncation or exon skipping while retain the amino-terminal transactivation and DNA-binding domains[48,49].Profiling of several AR-Vs revealed recruitment of these isoforms to androgen responsive elements in a ligand-independent manner, providing initial evidence for AR-Vs-sustained tumor growth without the need of ligand/androgens[50,51].AR-V7 is the best characterized isoform, showing nuclear localization in the presence of partial nuclear localization signal, and androgen-independent activity in AR transactivation reporter[49,52].

In prostate cancer cell-based models, the high expression of AR-Vs compared to AR full length (AR-FL) is associated with complex genomic rearrangements within the AR locus as exemplified by the 22Rv1 cell line harboring AR gene structural rearrangements and expressing high levels of AR-V7 relative to AR-FL[53,54].Clinical data of CRPC patients also confirm that AR genomic structural rearrangements are responsible for the expression of different AR-Vs, which are able to support constitutive and ligand-independent growth of tumor cells even in presence of antiandrogens[55].In addition, redistribution of splicing factors and high rate of AR gene transcription in response to ADT are also responsible for increased expression of AR-V7, as shown in VCaP and in a LNCaP derivative cell line[56].

The prognostic value of AR-Vs detection, and of AR-V7 in particular, is still unclear.AR-Vs can be detected in normal prostate tissue and early stage tumors, yet their expression seems to increase in CRPCs suggesting an evolutionary advantage for more aggressive disease.AR-V7 is significantly over-expressed in antiandrogen resistant tumors[52,57,58]and its expression is associated with resistance to abiraterone and enzalutamide in two cohorts of CRPC patients[59,60].This observation was recently confirmed in independent patients cohorts[61,62].Moreover, AR-V7 nuclear expression in circulating tumor cells was suggested as treatment-specific biomarker for metastatic CRPC (mCRPC) patients with short survival upon enzalutamide and abiraterone treatment and increased survival benefit on taxane therapy compared to AR-targeted therapy[63,64].However, a recent report did not support the predictive role of AR-V7 and AR-V9 detection in the circulation[65].

A direct link for AR-V7-induced resistance to enzalutamide was provided by the restoration of sensitivity to antiandrogens in 22Rv1 cells depleted of AR-V7[66].In this model AR-V7 seems to fully compensate for AR-FL function, yet other models expressing AR-V7 or other AR-Vs, such as VCaP cells, remain sensitive to androgen depletion and antiandrogens; furthermore, the growth promoting effect of AR-Vs remains dependent on AR-FL[7,67].Recent papers investigated the genomic binding of AR-FL and AR-V7 in CRPC cells and identified AR-FL and AR-V7 co-bound sites preferentially at ARE within enhancers.Interestingly,an additional subset of genes was bound and regulated uniquely by AR-V7[68,69].ZFX represents a crucial partner for AR-V7 binding at promoters, and the non-canonical gene expression program regulated by the two transcription factors promotes malignant growth of CRPC cells and is associated with poor prognosis[68].

Other mechanisms of resistance to ADT and AR-targeted therapies relying on AR and/or its regulated targets involve (1) maintenance of physiological intratumoral androgen levels, (2) dysregulated expression and/or mutation of AR cofactors, and (3) cross-regulation of AR targets by other nuclear receptors.

Following castration the levels of testosterone in circulation drop by > 90%.However the adrenal androgens dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione can serve as substrates for testosterone and DHT synthesis in the prostate replenishing the pool of androgens needed by the tumor cells[70,71].Furthermore,a gain-of-function mutation in the HSD3B1 gene was described in CRPC patients and in cell lines, such as LNCaP and VCaP, as increasing the stability of the enzyme and thereby enhancing the conversion of DHEA to intratumoral DHT[72].

Beside mutations and structural rearrangements affecting the AR locus itself, aberrations of other genes modulating the AR signaling pathway have been observed in metastatic disease[18,19,22,23].These include point mutations and amplifications of the pioneer factor FOXA1 in 10%-20% of mCRPC patients[73], amplifications/gains and mutations of the AR coactivator NCOA2[74], mutations and deletions in ZBTB16, NCOR1 or NCOR2, known AR corepressors[19,75].

Preclinical studies and indirect evidence support the hypothesis that other nuclear receptors [e.g.,glucocorticoid receptor (GR), progesterone receptor (PGR) and mineralcorticoid receptor] could substitute AR in gene regulation given the shared structure and the high homology of the DNA-binding domain[76].Indeed, upregulation of and dependence on GR were observed in LNCaP xenograft models resistant to enzalutamide.Moreover, it was shown that AR and GR have similar cistromes and that GR overexpression mediates the induction of a subset of AR target genes thought to be involved in resistance[77,78].More indirectly, in clinical cohorts of primary prostate cancers shorter relapse free survival was associated with high expression of PGR in situ[79].

GENOMIC FEATURES OF AR-INDEPENDENT RESISTANCE

Lineage plasticity is recognized as one possible mechanism to evade targeted therapy where cancer cells transition towards an alternative cell lineage that is not dependent on the target.This mechanism is active in a fraction of CRPCs under AR-targeted drugs pressure.Since the introduction of second generation in a fraction of CRPCs under AR-targeted drugs pressure.Since the introduction of second generation AR-directed therapies in the clinical management of CRPC patients, a significant increase in tumors with a continuum of neuroendocrine markers and morphological variants was observed[80-83]in up to 20% of resistant tumors[84,85].These tumors demonstrate epithelial plasticity and transition towards a predominantly AR-low neuroendocrine phenotype.Elegant work from Zou et al.[86]applied lineage tracing in vivo in genetically engineered mouse models resistant to abiraterone and developing tumors resembling treatmentinduced neuroendocrine disease in CRPC patients; the study provided quantitative evidence that both focal and overt neuroendocrine tumor regions arise via transdifferentiation from adenocarcinoma cells[86].A model of divergent clonal evolution in CRPC from adenocarcinoma to neuroendocrine phenotype was also supported by the largest genomic and molecular study in human samples (metastatic biopsies) designed to study the etiology and molecular basis for this treatment-resistant cell state.Where the genomic component of the study recognized a substantial genomic overlap between CRPC neuroendocrine and CRPC adenocarcinomas tumors, albeit with few exceptions (enrichment for TP53 and RB1 loss and depletion of AR amplification), the genome-wide methylation profiles detected marked epigenetic differences, suggesting epigenetic modifiers as possible players in the state transformation or maintenance; the transcriptomic component of the study further highlighted the dysregulation of specific pathways including neuronal and stem cell programs and epithelial-mesenchymal transition[87].

In 2017, two studies contributed novel insights into the mechanistic understanding of cell plasticity of prostate cancer cells resistant to androgen deprivation therapies[88,89].Altogether, they show that downregulation of TP53 and RB1 leads to increased expression of genes regulated by E2F transcription factor, including EZH2 and SOX2; that SOX2 induction contributes to AR pathway independence and lineage reprogramming, and that EZH2 inhibition leads to increase in AR and restoration of responsiveness to enzalutamide.Additionally, SOX2 activity is controlled by a master regulator of neural differentiation,BRN2, which is inhibited by AR and therefore active in AR-null tumors[90].More recently, in the attempt to look for shared vulnerabilities of small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas that arise from epithelial cancers under therapies inhibiting critical oncogenic pathways, Park and colleagues utilized human tissue transformation assays and tested the functional role of known main drivers[91].Starting from primary basal epithelial cells isolated from the prostates of human donors and a leave-one-out approach, they observed that inactivation of both TP53 and RB1 is required to reprogram the transcriptional profile and the chromatin accessibility of normal prostate epithelial cells to small cell prostate cancer; and that the same driver events can initiate small cell lung cancer from human normal lung epithelial cells.

Building on the initial observation that AURKA and MYCN are amplified and co-overexpressed[92]in neuroendocrine prostate cancer, Dardenne et al.[93], using MYCN transgenic mouse and organoid models,showed that N-MYC overexpression leads to the development of poorly differentiated, invasive prostate cancer, similar to human neuroendocrine tumors.They observed abrogation of androgen receptor signaling and induction of Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 signaling.Inhibition of Aurora-A resulted in decreased steady-state levels of N-MYC protein and of its target genes and in decreased cell viability, altogether suggesting exploitation of the mutual dependence of N-MYC and Aurora-A to revert their oncogenic functions in neuroendocrine disease.

Profiling of mCRPCs patients identified a double negative population of tumors (DNPCs) that shows a lack of both the AR program and of neuroendocrine markers[85,94].Interestingly, the proportion of DNPCs increases in cohorts of patients collected after the approval of more effective AR antagonists such as enzalutamide and abiraterone, suggesting a shift in the tumor phenotype probably linked to the use of these second generation antiandrogens[85].In vitro work showed that these double negative cells rely on FGF and MAPK activity for growth and targeting of this AR bypass pathway can be exploited for treatment of AR-null tumors[85].

ALTERNATIVE PROGRAMS OF RESISTANCE

The observation that a portion of prostate cancer samples overexpresses SPINK1, a trypsin inhibitor that protects the gastrointestinal tract from protease degradation, opened up to the possibility that a gastrointestinal (GI)-lineage specific expression program is activated to promote castration resistance.Accordingly, studies showed that SPINK overexpression is associated with worse prognosis and more rapid progression of resistant tumors[95-98]and a subclass of CRPC expresses high levels of hepatocyte nuclear factor 4-gamma (HNF4G) and 1-alpha (HNF1A)[99].These two master transcription factors sustain a GI transcriptional program in prostate cancer, present non-overlapping cistrome with AR, and their exogenous expression leads to resistance to androgen depletion and to enzalutamide in prostate cancer cell lines and xenograft models[99].

An alternative pathway that could sustain growth of prostate cancers is the WTN signaling pathway.Indeed,similar to colon cancers, mutations in CTNNB1 (encoding for β-catenin) genes, which lead to ligandindependent activation of the pathway, were identified in prostate cancer samples[100,101].Recent sequencing efforts comparing the genomic feature of primary and metastatic castration resistant tumors detected mutations in major components of the WNT signaling as being enriched in the latter[19,22].Moreover, high levels of WNT ligands are found in mCRPC samples and in vitro work supports a direct interaction between β-catenin and AR and a role for β-catenin in enhancing AR transcriptional activity[58,102-105].

CONCLUSION

Potent therapies often trigger resistance mechanisms that present or are facilitated by distinct genomic or molecular settings.Whereas functional studies are needed to reveal the mechanistic features of drug resistance, the role of large-scale genomic studies on contemporary cohorts of patients can nominate structural events associated to resistance that can eventually turn into biomarkers for treatment options.Recent work has also suggested that complex structural events possibly involving non-coding areas of the genome can contribute to our knowledge of disease progression.AR enhancer duplication[18,33,34]and RB1 exon 7-17 tandem duplication[106]leading to AR overexpression and RB1 protein loss respectively are relevant examples of events discovered through whole genome sequencing studies.Similarly, SNPs located in noncoding inter- or intragenic regions were shown to be associated with specific subtypes of prostate cancer and with disease aggressiveness[107-110].

The application of new therapeutic strategies to treat CRPC patients will further lead to the emergence of alternative mechanisms of resistance different from those identified so far.PARP and immune checkpoint inhibition in CRPC patients harboring defect in DNA repair pathways, such as homologous recombination and mismatch repair, and CDK12 inactivation[19,111,112]will profoundly shape the mutational landscape of prostate cancer in the future.The timely detection of mutations remains an issue of utmost importance for patient care.While liquid biopsy based studies provide promising venues to regularly monitor patients treatment response and to track tumor dynamics, proper assay design is required in order not to miss relevant new markers of resistance.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributions

Wrote this review: Lorenzin F, Demichelis F

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest

Both authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Copyright

© The Author(s) 2019.