Role of abdominal ultrasound for the surveillance follow-up of pancreatic cystic neoplasms: a cost-effective safe alternative to the routine use of magnetic resonance imaging

2019-06-04LucaMorelliSimoneGuadagniValerioBorrelliRobertaPisanoGregorioDiFrancoMatteoPalmeri

Luca Morelli, Simone Guadagni, Valerio Borrelli, Roberta Pisano, Gregorio Di Franco, Matteo Palmeri,

Niccolò Furbetta, Dario Gambaccini, Santino Marchi, Piero Boraschi, Luca Bastiani, Alessandro Campatelli,Franco Mosca, Giulio Di Candio

Abstrac t BACKGROUND Patients with pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN), without surgical indication at the time of diagnosis according to current guidelines, require lifetime imagebased surveillance follow-up. In these patients, the current Εuropean evidencedbased guidelines advise magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning every 6 mo in the first year, then annually for the next five years, without reference to any role for trans-abdominal ultrasound (US). In this study, we report on our clinical experience of a follow-up strategy of image-based surveillance with US, and restricted use of MRI every two years and for urgent evaluation whenever suspicious changes are detected by US.AIM To report the results and cost-efficacy of a US-based surveillance follow-up for known PCNs, with restricted use of MRI.METHODS We retrospectively evaluated the records of all the patients treated in our institution with non-surgical PCN who received follow-up abdominal US and restricted MRI from the time of diagnosis, between January 2012 and January 2017. After US diagnosis and MRI confirmation, all patients underwent US surveillance every 6 mo for the first year, and then annually. A MRI scan was routinely performed every 2 years, or at any stage for all suspicious US findings.In this communication, we reported the clinical results of this alternative followup, and the results of a comparative cost-analysis between our surveillance protocol (abdominal US and restricted MRI) and the same patient cohort that has been followed-up in strict accordance with the Εuropean guidelines recommended for an exclusive MRI-based surveillance protocol.RESULTS In the 5-year period, 200 patients entered the prescribed US-restricted MRI surveillance follow-up. Mean follow-up period was 25.1 ± 18.2 mo. Surgery was required in two patients (1%) because of the appearance of suspicious features at imaging (with complete concordance between the US scan and the on-demand MRI). During the follow-up, US revealed changes in PCN appearance in 28 patients (14%). These comprised main pancreatic duct dilatation (n = 1), increased size of the main cyst (n = 14) and increased number of PNC (n = 13). In all of these patients, MRI confirmed US findings, without adding more information.The bi-annual MRI identified evolution of the lesions not identified by US in only 11 patients with intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (5.5%), largely consisting of an increased number of very small PCN (P = 0.14). The overall mean cost of surveillance, based on a theoretical use of the Εuropean evidenced-based exclusive MRI surveillance in the same group of patients, would have been 1158.9± 798.6 € per patient, in contrast with a significantly lower cost of 366.4 ± 348.7 €(P < 0.0001) incurred by the US-restricted MRI surveillance used at our institution.CONCLUSION In patients with non-surgical PCN at the time of diagnosis, US surveillance could be a safe complementary approach to MRI, delaying and reducing the numbers of second level examinations and therefore reducing the costs.

Key words: Ultrasound; Pancreatic cystic neoplasms; Magnetic resonance imaging;Surveillance(CΕAVNO)”.

INTRODUCTION

The w idespread use of high resolution imaging has resulted in a marked increase in the incid ental d etection of p ancreatic cystic lesions, such that these lesions are encountered in 3% of abdominal computed tomography (CT) examinations and in up to 13%-19.6% of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans[1-3]. The MRI prevalence data are in agreement w ith the p reviously rep orted autop sy stud ies d emonstrating pancreatic cystic lesions in up to a quarter of cases[4]. Cystic pancreatic lesions are a heterogeneous group. The classification of pancreatic cyst neoplasms (PCNs) is based either on their neoplastic potential or their epithelial or mesenchymal origin.

The tw o most common PCN lesions are the intrad uctal p ap illary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN) and the mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN). Both are benign, but with an established risk of malignant progression; w hereas others are always benign,w ithout any risk for malignant transformation, e.g., serous cystic neoplasm (SCN).More rarely, PCN are overtly malignant at the time of d iagnosis (cystad enocarcinomas). PCN not only have diverse histological and imaging appearances, but also differ in their clinical presentation, biological behavior, grow th pattern, and risk of malignancy[5]. Accurate risk stratification and d ecisions regarding treatment and follow-up strategies necessitate precise lesion characterization and d iagnosis. Several recommend ations have been published on their p athology and management. The most relevant are the International Consensus Guidelines (2006[6], 2012[7]and 2017[8]),the guid elines of the American Gastroenterological Association (2015[9]), and the Εurop ean stud y group on cystic tumors of the p ancreas guid elines (2012[10]and 2018[11]). All these guidelines consider repeated MRI scans with similar frequency as the preferred surveillance tool in the follow-up strategy of non-surgical PCN. The Εurop ean evid ence-based guid elines on pancreatic cystic neoplasms consid er the presence of jaund ice, mural nod es (> 5 mm) and main duct d ilatation ≥ 10 mm as“absolute indications” for surgery. The presence of main duct d ilatation 5-9.9 mm,cyst grow th rate > 5 mm/year, mural nod es < 5 mm, cystic d iameter ≥ 40 mm,increased serum markers and new onset of diabetes or acute pancreatitis are relative indications for surgical intervention. In the presence of one or more of these features,surgical indication has to be balanced by the patients' general condition, including comorbid disorders.

Surgical intervention in the remaining “low risk” PCN (Wirsung diameter < 5 mm,cyst size < 40 mm, growth rate < 5 mm/years and no mural nodes) is not indicated at the time of diagnosis. Instead, accurate surveillance follow-up is recommended in the first instance. This consists of a MRI every 6 mo d uring the first year and then annually for the next 5 years, in ord er to d etect the ap p earance of p rogressive changes, e.g., an increase in the size of the major lesion, main p ancreatic d uct dilatation or mural nodules. Although MRI is considered the gold stand ard imaging technique[12-14]to follow-up on these lesions, it has some issues, includ ing limited access to this imaging modality and high costs[15,16]. In addition, MRI examinations are lengthy and can be uncomfortable for p atients, p articularly those w ho suffer from claustrop hobia. Ad d itionally, there are p atients in w hom MRI is contraindicated.Other imaging modalities used include endoscopic ultrasound (ΕUS) with or w ithout fine needle aspiration (FNA), transabdominal ultrasound (US), contrast enhanced US(CΕUS) and contrast enhanced-ΕUS (CH-ΕUS). ΕUS is recommend ed in the current guidelines as an adjunct to the other imaging modalities in the assessment of patients harboring PNC with features id entified d uring the initial investigation or follow-up,which may indicate the need for surgical resection. Despite its accuracy, ΕUS-FNA is invasive and thus should be performed only when the results are expected to change clinical management. Although US and CΕUS are includ ed in the Italian consensus guidelines for the diagnostic w ork-up and follow-up of cystic pancreatic neoplasms[17],this recommend ation is not includ ed in the Εuropean Εvidence Based Guid elines;although CH-ΕUS is considered for evaluation of mural nodules[11].

A p ragmatic approach is needed, especially in public healthcare hospitals, in the clinical management of patients harboring relatively common benign lesions but a varying risk of malignant transformation. Although these PCN do not require surgery at the time of d iagnosis, there is an evid ence-based absolute need for exp ensive image-based long-term surveillance follow-up. Hence, cost considerations, w ith the emp hasis on cost-efficacy and utility of long-term surveillance, is p articularly essential in public healthcare systems. However, in the quest for cost containment, an alternative cheaper follow-up system for non-surgical PCN is only acceptable if it is safe and p roven to be fit for purpose, i.e. if it does not miss malignant evolution of PCN. Recently, a few publications[18-20]have evaluated the role of US in monitoring PCN. Nevertheless, to date there has not been any reports of a safe alternative followup strategy based on US with limited MRI use outlined by the present study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients selection and data acquisition

Records from all patients with PCN d iagnosis w ithout indications for surgery(absolute or relative), w ho w ere enrolled in our modified surveillance protocol between January 2012 and January 2017, were reviewed retrospectively. The patient cohort for this retrospective study was obtained from our institutional, prospectivelycollected database and selected as patients with confirmed diagnosis of PCN without absolute or relative ind ications for surgery according to the current Εuropean evidence-based guidelines[11]. The diagnostic US criteria for suspect PNC were the id entification of one or more partial or completely anechoic areas w ithin the pancreatic parenchyma and/or dilation of Wirsung duct > 2 mm, in the absence of identifiable causes of obstruction. In the protocol, the US d iagnosis was always confirmed with an MRI scan. Εxclusion criteria were suspected or proven malignancy at the time of diagnosis (presence of solid vascularized tissue in the cyst, presence of nodal or distant metastasis at imaging, or positive histopathological findings)[18], PCN with absolute or relative surgical criteria[11], clear d iagnosis of SCN, absence of diagnostic MRI scan, and follow-up period less than 10 mo. The last date of entrance into the US follow-up for the group of patients included in the study was January 1,2017, with an end-point date of January 1, 2018 for the surveillance follow-up period.

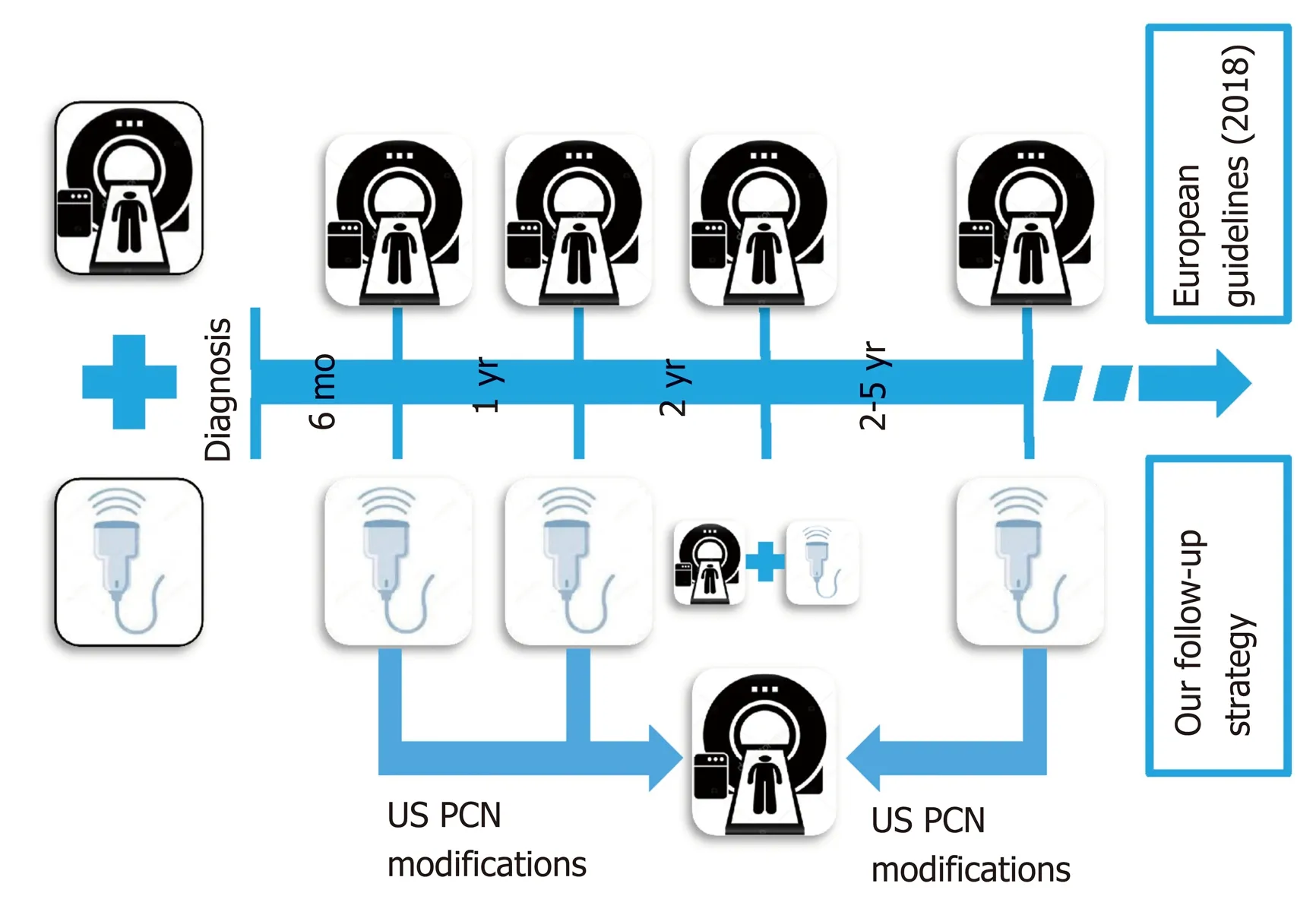

After US diagnosis and MRI confirmation, all scheduled patients were followed-up with a non-conventional surveillance protocol that was used in our Unit since 2012. It consisted of a US scan every 6 mo for the first year and then, in patients with stable disease, annually from the second to the fifth year. A planned MRI was performed routinely every two years for stable disease, or at any time when suspicious changes were observed on US. Abdominal US was always performed just before the planned routine MRI in the second year of follow-up (Figure 1). The reasons for reducing the imaging intervals and advancing the MRI were dilatation of the main duct > 50%,increased size of the cyst ≥ 2 mm from previous examinations, or development of new lesions (Figure 2). The development of new PCN is diagnosed by conventional US as a new anechoic area into the pancreatic parenchyma. Stable disease was defined as PNC without detectable changes between two subsequent follow-up images.

Retrieved data included baseline patient characteristics, Wirsung caliber (the widest portion regardless of location), PCN size (largest diameter), connection of the cyst to the ductal system, and numbers and locations at the time of diagnosis. The duration of the follow-up period, Wirsung caliber, PCN modifications discovered during surveillance with subsequent performance of US as a follow-up examination,and MRI were also evaluated. Finally, the number and cost of US and MRI performed for each patient were obtained.

Costs of a single examination w ere expressed in Εuros and obtained from our regional rates as follows: 60 € for US and 480 € for MRI, with an extra 254 € for a contrast-enhanced study. The total number of US and MRI scans (both routine and urgent) for each patient included in the study, together w ith the total number of examinations, were obtained. In the same way, the overall number of MRI alone,which would have been performed if the same patient group had undergone the standard guidance-approved MRI only surveillance[11], were calculated. According to the guidelines, a short MRI protocol without the administration of contrast provides equivalent information to a longer contrast enhanced MRI p rotocol for the surveillance of PCN. As a consequence, the MRI exam in the ‘virtual' control group was estimated as 480 € and scheduled, as suggested, every 6 mo. This enabled the calculation of the theoretical overall cost of the control group.

These data w ere used in the cost-analysis comparison betw een the US-MRI restricted surveillance-based follow-up strategy and surveillance had the same group of patients been subjected to the evidenced-based existing guidelines surveillance with MRI alone. Sensitivity, negative predictive value, and the accuracy of US with respect to MRI in the follow-up were evaluated. Specifically, the sensitivity, negative predictive value and accuracy refer to the ability of US to detect changes in PNC, with respect to the gold standard MRI at two years. The diagnostic criteria evaluated for this analysis are the same for both US and MRI, which include a detected increase in the number of PCN (detection of new anechoic areas not identified in previous examination; increased of size PCN > 2 mm; increase of Wirsung caliber > 50%). In this series, no patients developed mural nodules or PCN wall thickness. Hence, these were not included in the analysis.

Imaging protocol

Figure 1 The two follow-up strategies comprising the standard magnetic resonance imaging vs nonconventional abdominal US surveillance. US: Ultrasound; PCN: Pancreatic cyst neoplasms.

B-mode US w as performed in all patients at our department by surgeons with expertise in US examinations and with over 25 years of experience in pancreatic surgery and imaging. All patients signed an informed consent to authorize the scientific use of the collected d ata. A GΕ Logiq 9 (GΕ Healthcare, Milw aukee, WI,United States) w ith a p robe frequency of 3.5-5.0 MHz w as utilized. Patients w ere scanned sup ine or in other p ositions w ith grey scale imaging and Color-Dop pler.Harmonic imaging w as routinely used to red uce artefact and increase the signal-tonoise ratio. The p osition, size, boundaries, and contents of all PCN, as w ell as the diameter of the pancreatic duct, if visible, w ere record ed. During the examinations,previous US or MRI images, including those performed at the time of diagnosis, were available using Resolution and then Suit Εstensa PACS (Εsaote Spa, Genova, Italy).They w ere used as correlative images to id entify know n PNC and evaluate their modifications. CΕUS w as only used occasionally in a few selected p atients w ith relative surgical ind ications, which had show n at the time of the diagnosis septa or cystic w all thickness by B-mod e US. Hence, it w as not consid ered in the present analysis.

Patients und erw ent MRI on a sup ercond uctive 1.5T system (Signa HDx; GΕ Healthcare) using a tw elve-channel phased-array bod y coil for both excitation and signal reception. Immediately before starting the examination, scopolamine methylbromid e (20 mg; Buscop an®, Boehringer Ingelheim, Italy) w as ad ministered intramuscularly to avoid p eristaltic artefacts. The stand ard imaging p rotocol includ ed, first, T1-w eighted breath-hold SPGR in-p hase and out-of-p hase axial sequences (w ith and/or w ithout fat suppression), and T2-w eighted axial sequences(both breath-hold, single-shot fast spin-echo and respiratory-triggered, fat-suppressed fast spin-echo) of the upper abdomen. Next, MRCP w as performed by respiratorytriggered, three-dimensional, heavy T2-w eighted fast spin-echo (3D FRFSΕ) sequence and breath-hold, thick-slab, single-shot FSΕ T2-weighted sequences performed in the coronal and oblique-coronal p rojections. Diffusion-w eighted MR imaging of the pancreatic region was performed using an axial respiratory-triggered spin-echo echoplanar sequence w ith multiple b values (300, 500, 700, 1000 s/mm²) in all diffusion directions. If there w ere some doubts on the pre-contrast study, a three-dimensional fat-suppressed Liver Acquisition with Volumetric Acceleration (LAVA) sequence was obtained in the axial and sometimes coronal plane before and after intravenous injection of Gad olium-based contrast agents. Post-contrast graphic images w ere obtained in the arterial, portal-venous and d elayed (betw een 3 and 5 min) phases.Acquisition time for the whole examination ranges from 30 to 35 min. The size of the voxels and therefore the spatial resolution depends on matrix size, the field-of-view(FOV), and slice thickness. Moreover, higher magnetic field allow s imp roved resolution. In our stud y, the MR cholangiograp hy matrix w as 256 × 160, the slice thickness/spacing was 2.4/-1.2 mm, and the FOV w as about 40. By applying these parameters, the 1.5 T MR device allow ed evaluation of variation in the dimension of 2 mm. The spatial resolution of the 1.5 T MR commercial device has been reported in the literature by Arizono et al[21]as 1.1 × 1.0 mm (inplane resolution) and 0.84 mm(minimum slice resolution).

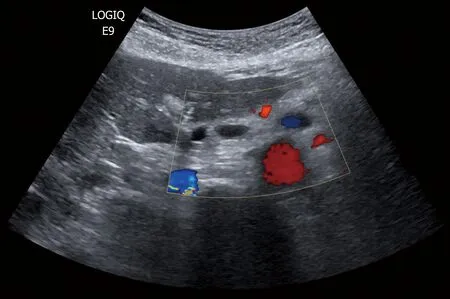

Figure 2 Development of new pancreatic cyst neoplasms as new anechoic areas into the pancreatic parenchyma detected by conventional ultrasound.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) and STATA version 13(STATA Corp., College Station, TX, United States) softw are w ere emp loyed for statistical evaluation. Continuous variables are reported as mean ± standard deviation(SD) and compared using Stud ent's t-test. Variables w ith a non-normal distribution are expressed as median and compared using the Wilcoxon Test. To d etermine the competency of US policy in the surveillance period relative to the gold standard MRI,a receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) test was performed w ith a calculation of sensitivity, negative predictive value, accuracy and area under the curve (AUC). P values less than 0.05 w ere considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

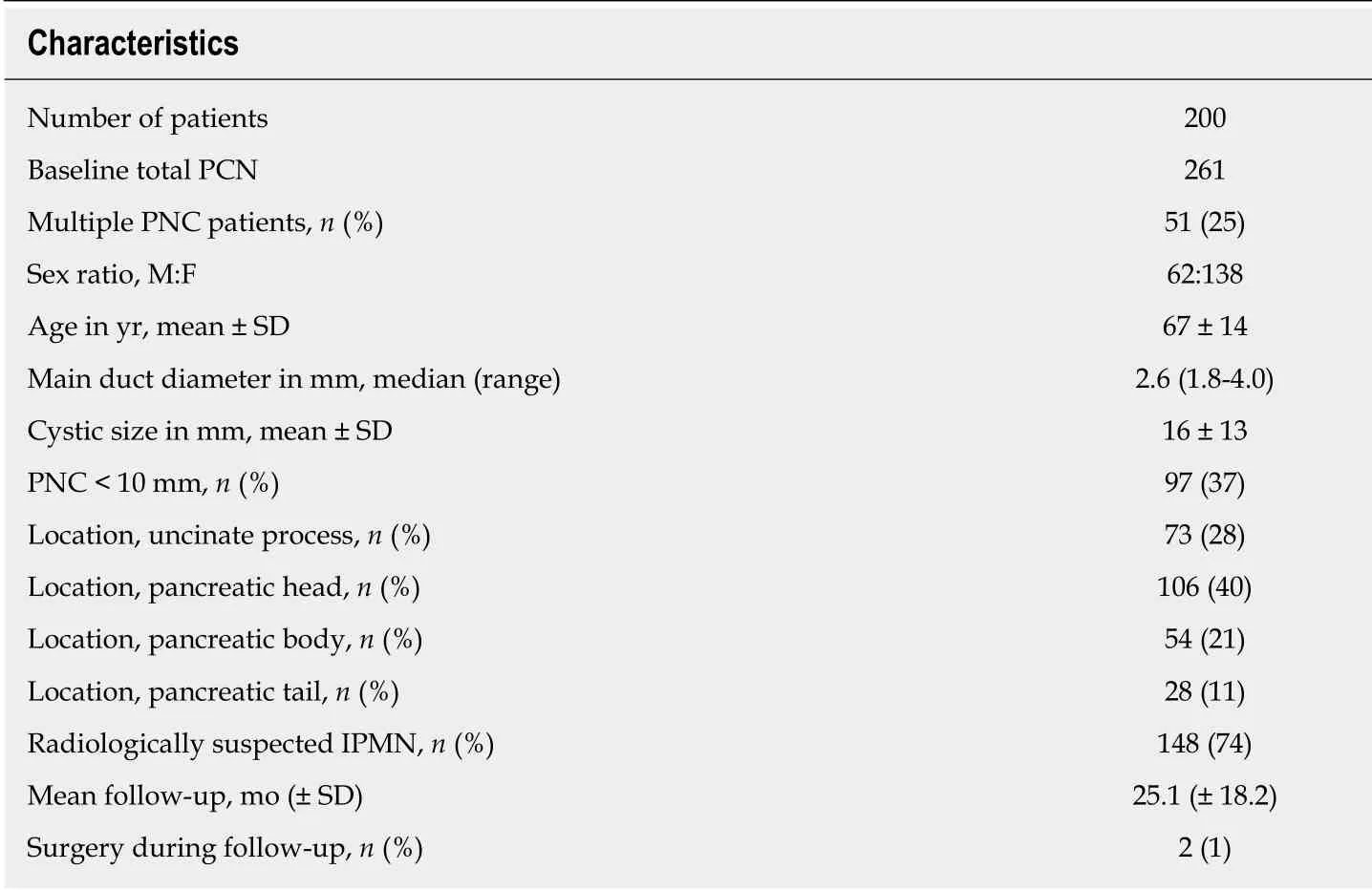

Two hundred patients harboring 261 PCN were followed-up with the US-Restricted MRI surveillance program described above. At diagnosis, 140 patients (74.5%) had a single PNC and 51 patients had multiple PNC (25.5%), the multiple PNC being referred to as IMPNs. The median number of cysts was two (range 2-5). The study group comprised 138 (69%) females and 62 (31%) males with a mean age of 67 ± 14 years. At the time of diagnosis, the median Wirsung diameter was 2.6 (range 1.8-4.5 mm) and the mean cystic diameter was 16 ± 13 mm, with 97 (37%) measuring less than 10 mm. Most lesions were located in the pancreatic head (106 PCN, 40% of total).Connections to the ductal system and MRI diagnosis of IPMN was documented in 148(74% of total patients). The mean follow-up period was 25.1 ± 18.2 mo. Surgery was required in two patients (1%) because of the appearance of suspicious features on the surveillance scans (with complete concordance between the US and the on-demand MRI scans). In the first patient, a 35 mm lesion located in the tail was detected by the 1-year US scan, which confirmed a rapid increase in cyst diameter reaching 42 mm.After MRI, ΕUS was also performed. However, due to the distal localization of the lesion and poor acoustic window, needle aspiration was not performed. This female patient was treated by laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy. Pathological examination of the excised specimen confirmed a cystic neuroendocrine tumor. For the second patient with a PCN located in the pancreatic head, follow-up imaging showed a progressive Wirsung dilatation that was accompanied by a rising serum Ca 19.9 level and, hence, had clear-cut indications for surgery. The final histologic diagnosis of the excised lesion was confirmed as a mucinous carcinoma arising from IPMN and staged T2N0M0. Data summarized in Table 1.

In 28 patients (14%), US showed non-surgical changes in PCN during surveillance,consisting of pancreatic duct dilatation in one case (from 2 to 3 mm) and an increase in diameter of the main cyst in 14 cases (median increased = 2.5 mm; range 2-5 mm). One female 88-year-old patient with PCN in the head of the pancreas that enlarged by 5 mm in one year was treated conservatively because of significant ischemic heart disease and diminished cardiac function. The lesion remained stable during a follow-up of 28 mo. In the remaining 13 patients, US discovered new cystic lesions during image-based surveillance. All these patients underwent MRI, which confirmed the US findings.

Table 1 Patient characteristics

In 11 patients (5.5% of total), the routine 2 years MRI identified evolution of the lesions not detected at the same time US (P = 0.14), but mainly related to an increased number of PCN (6 cases; 54%). In all these cases, the new PCN detected by MRI were located in the uncinate and tail of the pancreas. In five cases (46%), the routine MRI demonstrated a median PCN enlargement of 3 mm (range 3-4 mm) not detected by US. However, all these patients had PCN diameters < 15 mm and an MRI every 6 mo would not have altered the clinical management of these patients. In the present study, the follow-up surveillance program did not identify the development of mural nodules or thickness of the wall either by US or MRI.

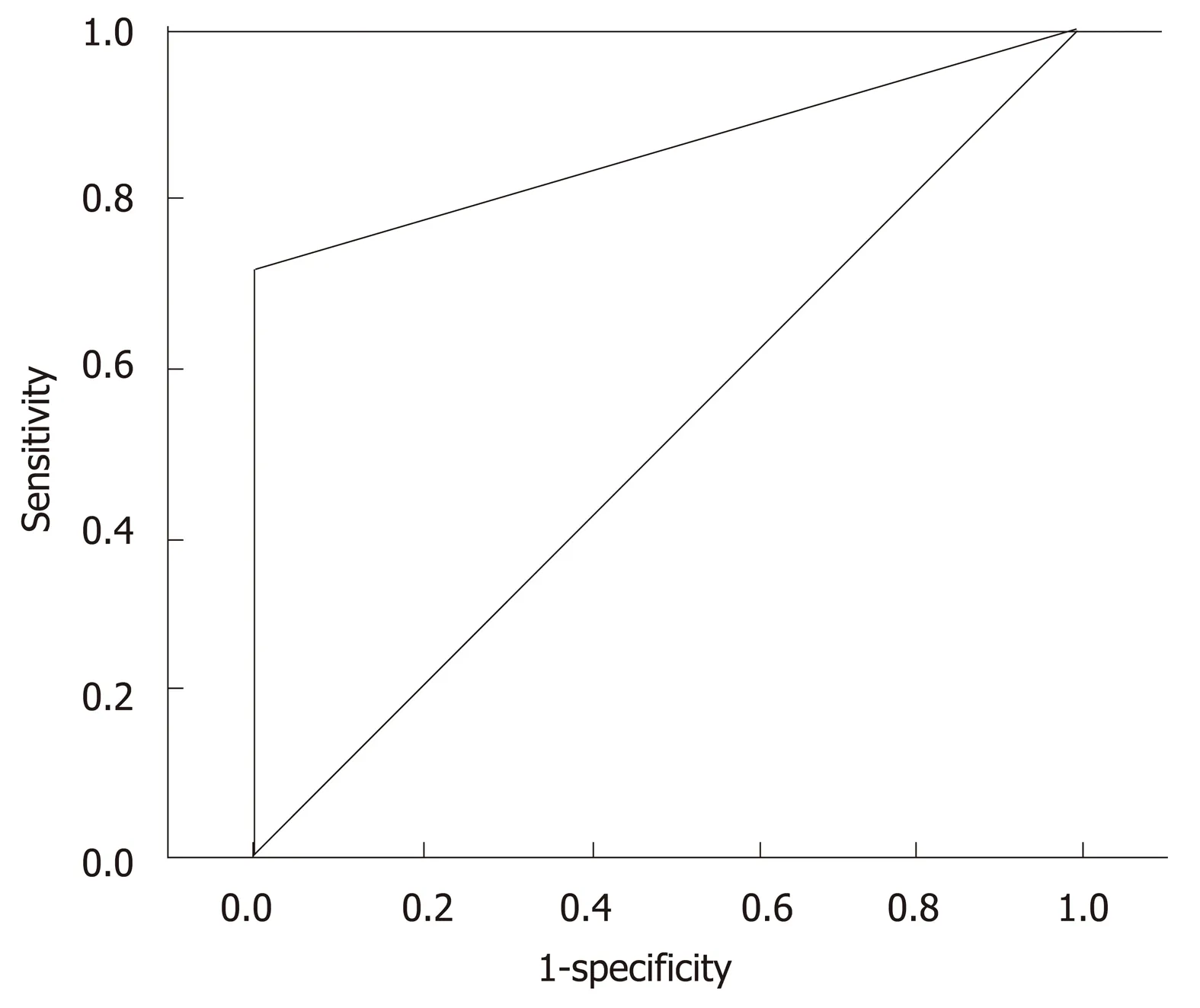

Considering the MRI as the gold standard, US used in PCN surveillance showed a sensitivity of 72%, negative predictive value of 94%, accuracy of 95% and AUC of a ROC curve of 86% (confidence interval 77%-94%, P < 0.001) (Figure 3).

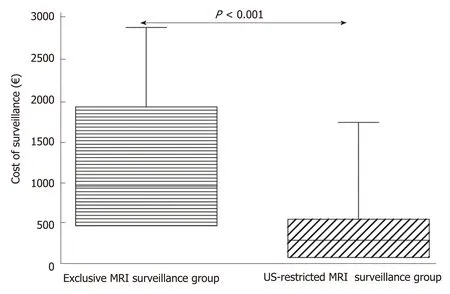

The mean cost of surveillance for each patient according to the proposed USrestricted MRI surveillance follow-up strategy was 366.4 ± 348.7 €. Had we used the surveillance recommended by the Εuropean evidenced-based guidelines with MRI in the same group of patients, the costs incurred would have been 1158.9 ± 798.6 € (P <0.0001), i.e. nearly trebled (Figure 4).

However, the cost of our proposed US-restricted MRI-based surveillance could be higher than the above cost of 366 ± 349 €, since it would be influenced by the number of patients with PCN requiring urgent MRI. This is because of changes documented by surveillance imaging (total = 30 in present cohort) and/or the need for a contrastbased MRI scanning contrast phase (n = 5 in present study). The overall costs of our proposed follow-up strategy still remain significantly lower than the exclusive MRIbased surveillance, i.e. 907.2 ± 382.9 € vs 1511.6 ± 790.4 € respectively, P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The crucial objective in the clinical management of patients harboring PCN is the early id entification of those at high risk of malignant degeneration[22]. To this effect,MRI is consid ered the gold stand ard imaging mod ality[13]in all the p ublished guidelines[8,11], both in the diagnostic workup and in the subsequent follow-up. MRI is useful for establishing the d iagnosis and presence of any connection between PCN and the ductal system, the baseline cystic diameter and other features. Likew ise, the follow-up imaging-based surveillance used has to be cap able of the risk features/changes pred ictive of neoplastic evolution[23-25]. Despite its proven efficacy,MRI has certain issues, including contrast-related side effects, claustrophobia, limited accessibility and high costs. ΕUS is helpful in resolving PCN w ith suspicious features,but on its own exhibits modest useful diagnostic performance for these lesions.How ever, w hen combined with fine-needle aspiration (FNA), the diagnostic yield and accuracy of ΕUS are increased significantly. Nevertheless, because of the invasive nature of FNA, this combination should be reserved in selected PNC cases with suspicious features on the MRI that suggest a need for surgery. Otherwise, because of its invasive nature, ΕUS with FNA is not suitable or recommended as a surveillance follow-up modality[11].

Figure 3 Receiver operating characteristic analysis showing the accuracy of ultrasound in the follow-up respect to gold standard magnetic resonance imaging performed 2 year after diagnosis vs those performed“on demand” during the follow-up.

In the management of patients with PCN who are largely asymptomatic and often young, within the context of increasing costs of secondary and tertiary healthcare in both public and private hospitals, cost considerations cannot be ignored. The clinical management of patients is essentially based on image-based surveillance follow-up,and we need an imaging protocol that is both fit for purpose and affordable. In this context, US is an imaging modality worthy of consideration as an alternative imaging modality in the follow-up of PCN. US can be used to evaluate most patients by assessing pancreatic duct caliber, diameter of the wall, and the internal aspect of pancreatic cysts[19]. US scanning for the detection and evaluation of PCN has been analyzed in a few reports, with the most important being the report by Sun et al[19].This seminal publication is based on a study involving 57 patients who underwent blinded US on the same day that each had an MRI. The authors demonstrate that an abdominal US for established PNC provides visualization and accurate measurement of many PCN of the cyst size, location, and other lesion characteristics. The conclusion from this study w as that US w as a valid adjunct of MRI in monitoring patients harboring PCN diagnosed by MRI. In another recent report, Jeon et al[20]reported that the detection rate and utility of US is significantly improved by repeat imaging if the initial diagnostic US image is available for use as a reference map; thereby confirming the increased usefulness of US in PCN surveillance. Apart from the patients' stature,the cyst location, availability of initial (baseline) images that affect US successful evaluation, and different PCN changes are not detected equally by US. In line with these studies, we have shown that during follow-up, Wirsung duct caliber and cyst d iameter are the factors that are w ell-visualized w ith US scan, w hereas the development of new cysts and small mural nodes are detected less successfully. When detectable, the US features indicative of the development of new cysts and small mural nodes includ e the appearance of new anechoic areas in the pancreatic parenchyma and the appearance of a solid iso/iper-echoic component inside the anechoic cystic area[26].

Figure 4 The box-plot graph showing the statistical difference between the overall cost for MRl alone and US-restricted MRl surveillance follow-up. US: Ultrasound; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Although dilatation of pancreatic duct caliber was clearly detected by US, the growth rate of PCN was missed in five cases and detected by MRI. However, all these missed lesions that measured smaller than 15 mm did not affect management. The development of new cyst(s) in other part of the pancreas was the main limitation of US surveillance, largely due to the inability for complete US exploration of the gland.However, the clinical importance of detecting small new PCN remains debatable.Since the clinical records of the patients included in the present study contained no data on mural nodes, the ability of US to detect these changes was not evaluated.Nevertheless, our view is that with conventional US, the difficulty of distinguishing genuine mural nodes from mucin plugs is substantial. CΕUS can be useful to enhance the ability of conventional US to image and d etect changes in the inner w all of pancreatic cysts[27]. In some reports[20], CΕUS alone has not been found to be useful or reliable in d ocumenting susp iciou s abnormalities that w arrant change in management. In ad d ition, these stud ies consid er MRI to be better for d etecting malignant transformation of IPMN, such that a detected intra-cystic solid mural node inevitably requires a second level MRI exam, thus limiting the utility of CΕUS. The use of US as part of the surveillance protocol in the follow-up of patients with PCN has certain advantages: ease of performance by fully trained ultrasonographists, fast,widespread availability, and low cost.

The main potential risk of delaying the MRI imaging routine could be to miss early detection of w orrisome features, how ever this has never been found in this stud y.Furthermore, even in this instance, the additional risk appears to be very low. In fact,relative ind ications for surgery according to Εuropean evidence-based guidelines[11]are not an expression of degeneration but only of increased risk, which is estimated in about 5.7% in patients w ith one relative indication for surgery[28].

Although CΕUS has been proven to be more sensitive than US, it is a more complex procedure to be performed, requires venous access and the availability of the contras med ia, and is more time-consuming and costly (about d ouble w ith resp ect to a conventional US). Furthermore, CΕUS is not as p anoramic as the MRI, because the various p hases must be focused only on a p recise target instead of on the w hole gland.

For these reasons, w e think that CΕUS is a good d iagnostic technique in selected cases, particularly w hen w e have to stud y a precise find ing of a B mode US, as an alternative or complimentary study to MRI. How ever, it is not a good technique for a routine follow-up.

The results of the present stud y ind icate the p otential benefit of includ ing US scanning w ith restricted MRI, as outlined in our hospital protocol, for surveillance of patients w ith PCN. The study has confirmed that restricting MRI imaging to patients with progressive PCN modifications identified by abdominal US can reduce hospital costs w ithout incurring missing patients w ho d evelop changes that require prompt surgical intervention or overt malignant transformation. Several stud ies[29-31]have confirmed the utility and importance of a cheaper imaging alternative to the MRI protocol. In our institution, the MRI protocol includes diffusion-w eighted imaging for a more reliable definition of suspicious PCN elements, together w ith the routine use of contrast-enhanced sequences. The routine MRI sequences differ substantially from those rep orted by Pozzi-Mucelli et al[30], and our costs seem low er d esp ite the comprehensive protocol. In Italy, several factors influence the imaging workflow, and these include examination time. US is the most acceptable imaging modality in this setting because it is quick, w idely accessible and low cost. This is confirmed by the Italian Consensus guid eline for diagnostic w ork-up and follow-up of PCN[17]. This may be different in other countries where a short MRI is preferred.

The primary goal of any surveillance program is to red uce the frequency of highlev el tests exemp lified by MRI w ithout comp romising p atient safety. The shortcomings of US are related to the patients' acoustic w ind ow and the und eniable fact that US is operator-d epend ent. Hence, the successful outcome of the p resent study may be related to the expertise of the surgeon US operators involved. For this reason, we believe that this program should be follow ed only in tertiary care hospitals by a d ed icated team w ith sp ecialist exp ertise in managing p ancreatico-biliary d isord ers. Εven so, there can be no doubt that patients/PNC locations w ith poor acoustic w ind ow cannot be safely follow ed by US. In our op inion, the stand ard exclusive MRI surveillance is needed for the follow-up of these patients.

We acknow ledge that the study has some limitations. The first is its retrospective nature, w hich p revented the inclusion of p atients w ith PCN w ho could not be assessed by US because of a poor acoustic w ind ow, thereby increasing the risk of selection bias. How ever, in the literature, cases w ith p oor acoustic w ind ow s preclud ing US assessment are not common and range from 2%-12% of cases[32]. The retrosp ective nature of the stud y may also influence extrapolated cost estimations based on the same cohort of p atients und ergoing surveillance by exclusive MRI surveillance. Another limitation of the study is the short follow-up, as this may inflate the p erformance of US since many PCNs remained unchanged d uring the stud y period. Clearly, the tw o surveillance regimens for p atients w ith PCN (MRI-based surveillance (current gold stand ard) vs our proposed US-restricted MRI surveillance protocols) need to be evaluated and confirmed by a p rosp ective RCT w ith both clinical and health economic endpoints.

In conclusion, in patients w ith good US w ind ow, and w ith PCN without absolute or relative surgical criteria, abdominal US performed by an expert physician could be a safe complementary approach to MRI. This would delay and reduce the numbers of second-level examinations and therefore reduce the cost of surveillance. Consid ering the grow ing pressure for the allocation of healthcare resources, US is an inexpensive op tion for follow-up of a large number of PCN p atients in a protracted p eriod.How ever, the proposed abd ominal US-restricted MRI surveillance protocol needs to be evaluated and confirmed by a prospective RCT against the currently recommended MRI-based surveillance, w ith the RCT having both clinical and health economic endpoints.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The current international guidelines only consider magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for the follow-up of patients w ith pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN). Given the great number of patients w ith PCN that have to be follow ed-up due to the inherent risk of malignant progression,the use of abdominal ultrasound (US) might be a quick, easily accessible and cost-saving imaging modality. Recent publications have evaluated the role of US in monitoring PCN, but none have proposed a safe alternative follow-up surveillance based on US w ith restricted MRI use.

Research motivation

We performed this study in order to evaluate the safety and cost-efficacy of US as a diagnostic tool to simplify the follow-up of selected patients w ith low risk pancreatic cystic neoplasms.

Research objectives

The objectives of this study were: (1) to evaluate the safety of the use of US in the surveillance of patients w ith good acoustic w indow and low-risk pancreatic cystic neoplasms; and (2) to propose an alternative follow-up protocol that reduces the cost with respect to the cost incurred by current international guidelines.

Research methods

We retrospectively evaluated the safety and costs of a follow-up surveillance for patients w ith low-risk PCN, performed with 6 monthly abdominal US for the first year, and then annually and w ith recourse to MRI scans performed every 2 years, or for confirmation of suspicious US findings.

Research results

Betw een January 2012 and January 2017, w e follow ed 200 patients w ith a specific protocol that included abdominal US scans for pancreatic cystic neoplasms. During a follow-up period of 25.1± 18.2 mo, MRI identified evolution of the lesions not detected by US in only 11 patients (5.5%).How ever, MRI every 6 mo w ould not have changed patient management in any case. The mean cost of surveillance for each p atient based on theoretical app lication MRI surveillance(recommended by international guidelines) w ithin the group of patients included in the study w ould have incurred costs of 1158.9 ± 798.6 €, compared to the surveillance costs incurred by the proposed US-restricted MRI protocol of 366.4 ± 348.7 € (P < 0.0001).

Research conclusion

Abdominal US seems to provide a cost-effective surveillance that reduces the frequency of MRI scans without affecting patient outcome. This is important in reducing the financial burden on hospital healthcare, aside from reducing the examination time and MRI-related issues and side effects. For patients w ith PCN, w e have proposed a follow-up surveillance that includes abdominal US, and demonstrated that it is safe and complementary to MRI. In addition, it effectively d elays and reduces the number of MRI scans, thereby reducing the cost of surveillance.

Research perspectives

The results of the present study need to be confirmed by a comparative prospective randomized trial w ith both clinical (long-term patient outcome safety) and health economic primary endpoints.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Sir Alfred Cuschieri for constructive criticism and for providing language editing.

杂志排行

World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Alteration of the esophageal microbiota in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma

- lnflammatory bowel diseases and spondyloarthropathies: From pathogenesis to treatment

- Harnessing the potential of gene editing technology using CRlSPR in inflammatory bowel disease

- Diversity of Saccharomyces boulardii CNCM l-745 mechanisms of action against intestinal infections

- Characteristics of mucosa-associated gut microbiota during treatment in Crohn's disease

- Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir + dasabuvir +/- ribavirin in real world hepatitis C patients