Prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants – an updated review

2019-05-10YuTingJinYueDuanXiaoKaiDengJingLin

Yu-Ting Jin, Yue Duan, Xiao-Kai Deng, Jing Lin

Abstract

Key words: Necrotizing enterocolitis; Prevention; Human milk feeding; Probiotics;Empiric antibiotics; Standardized feeding protocols

INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is among the most common and devastating diseases encountered in premature infants, yet the true etiology continues to be poorly understood, despite decades of research. Prematurity remains the most consistent risk factor, although term babies can develop NEC with a much lower incidence. Based on a recent large study from the Canadian Neonatal Network, approximately 5.1% (1.3%-12.9%) of infants with a gestational age < 33 wk develop NEC, and the incidence increases with decreasing gestational age[1]. Despite advances in care in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), the estimated mortality rate associated with NEC ranges between 20% and 30%, with the highest rate among infants requiring surgery.Following recovery from the acute phase of NEC, long term complications include intestinal stricture and short bowel syndrome[2-4].

The classical presentation of NEC includes feeding intolerance, abdominal distension, and bloody stools after 8-10 d of age when feeding enterally. The signs and symptoms are quite variable, ranging from feeding intolerance to evidence of a fulminant intra-abdominal catastrophe with peritonitis, sepsis, shock, and death.Many theories have attempted to elucidate the true pathogenesis since Santulli et al[5]first described a series of NEC cases in premature infants with respiratory distress syndrome. Most theories about the pathogenesis of NEC have focused on the most important risk factors, such as immaturity, formula feeding, and the presence of bacteria[6]. More recently, gut bacterial dysbiosis has been proposed as the main risk factor for the development of NEC[7]. Based on this theory, several best clinical strategies are being recommended to reduce the risk of NEC. These include breast milk feeding, restrictive use of antibiotics, supplementation with probiotics, and standardized feeding protocols (SFPs). The purpose of this review is to summarize the results of the recent clinical trials that provide evidence supporting these practices in premature infants as methods to reduce the risk of NEC.

LITERATURE REVIEW

A search was conducted in PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) for studies published before 15 June 2018. The search included all terms related to NEC and preventive interventions, including human milk feeding, probiotics, prophylactic antibiotics, and SFPs, utilizing PubMed MeSH terms and free-text words and their combinations through the appropriate Boolean operators. Similar criteria were used for searching MEDLINE. The review was limited to clinical studies involving human subjects. All relevant articles were accessed in full text following PRISMA guidelines.The manual search included references of retrieved articles. We reported the results in tables and text.

HUMAN MILK FEEDING

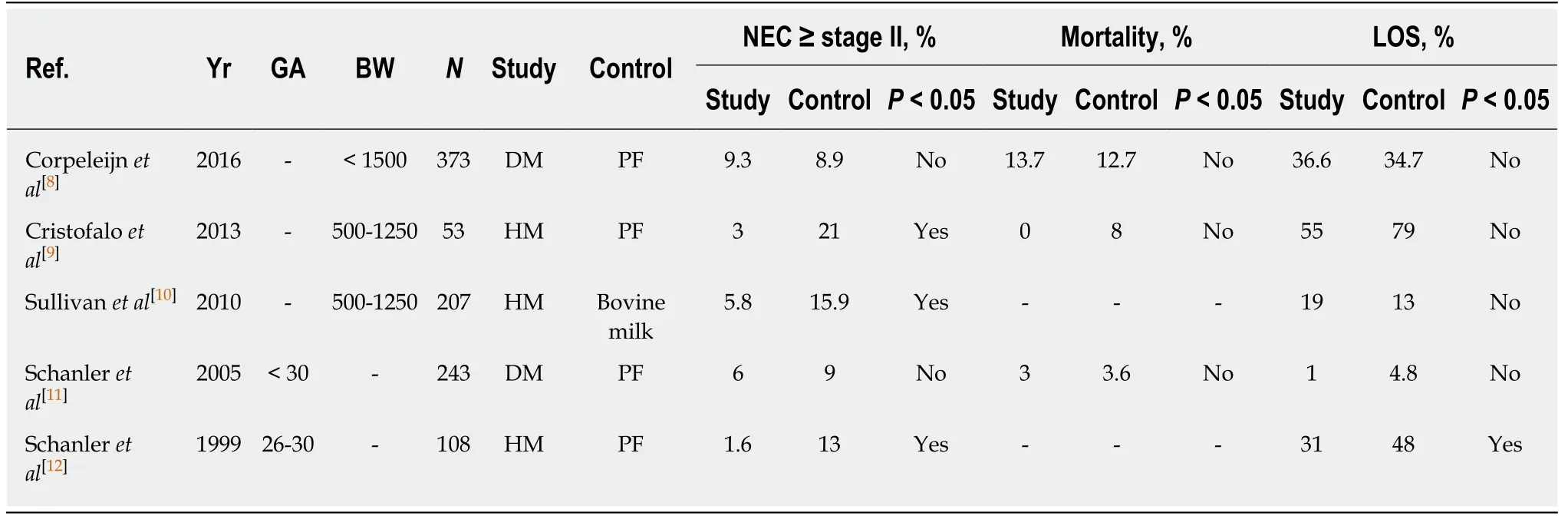

The unique properties of human milk promote an improved host defense and gastrointestinal function. Several well controlled clinical trials have demonstrated that human milk feeding can reduce the incidence of NEC. The results of the recent randomized trials are summarized in Table 1[8-12]. Cristofalo et al[9]and Schanler et al[12]demonstrated that human milk feeding could reduce the incidence of NEC in premature infants compared to those fed with preterm formula in their randomized trials. Sullivan et al[10]studied a total of 207 infants and found that feeding with an exclusively human milk-based diet is associated with a significantly lower rate of NEC than a diet of human milk fortified with bovine milk-based products. Human milk feeding also reduces the incidence of late onset sepsis in premature infants[12].

Human donor milk is considered a safe alternative when the mother's own milk is not available. When the mother's breast milk supply was deficient, the short-term outcomes related to safety and efficacy were similar in very low birth weight (VLBW)infants who were fed with pasteurized donor milk or with preterm formula in the first 10 d of life[8]. For feeding extremely preterm infants, donor milk offered little shortterm preponderance over preterm formula[8,11]. However, by using the Cochrane Neonatal search strategy, Quigley et al[13]performed a systematic review and metaanalysis of formula versus donor breast milk for feeding preterm or low birth weight(LBW) infants. They identified 11 randomized or quasi-randomized trials in which 1809 infants participated, and they concluded that donor milk feeding decreased the risk of NEC based on the meta-analysis. However, formula-fed infants had higher inhospital rates of weight gain, linear growth and head growth[13]. Furthermore, infants fed with donor human milk-based fortifier had approximately 64% lower odds of developing NEC compared to those fed with bovine-based fortifiers[14]. It is clear that human milk feeding can reduce the risk of NEC. Recently, the policy statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics on the use of human breast milk states that preterm infants should only receive their own mother’s milk or pasteurized human donor milk when their own mother’s milk is not available[15].

Human milk colostrum is high in protein, fat-soluble vitamins, minerals, and immunoglobulins. The benefit of colostrum for newborn infants has been well established. However, most extremely premature infants are usually not ready to be fed in the first few days of life for a variety of reasons. Several studies support the use of colostrum for oral care to provide immunotherapy in preterm infants. The efficacy of oropharyngeal colostrum therapy (OCT) in the prevention of NEC in VLBW infants has been reviewed, and a meta-analysis on this topic was recently published[16]. Only randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized trials performed in VLBW infants or preterm infants with gestational age < 32 wk were included for the meta-analysis.As a result, a total of 148 subjects (77 in OCT arm and 71 in control arm) in four trials were analyzed, and no statistically significant difference in the incidence of NEC was demonstrated. The authors concluded that the current evidence was not sufficient to enable the recommendation of OCT as a routine clinical practice in the prevention of NEC[16].

ADMINISTRATION OF PROBIOTICS

Establishment of a normal intestinal microbial colonization after birth is vital for proper maturity of the innate immune system and maintenance of intestinal barrier function. It has been proposed that disruption of the normal gut microbiota formation may play a major role in the pathogenesis of NEC in premature infants[17]. Probiotics are live micro-organisms that, upon ingestion at certain amounts, confer health to the host. It is known that probiotics can produce bacteriostatic and bactericidal substances, thus having immunomodulatory effects; furthermore, they prevent colonization of pathogens by competing for adhesion to the intestinal mucosa[18]. One strategy to prevent NEC is oral administration of probiotics to alter the balance of the gut microbiome in favor of non-pathogenic bacteria. In the past two decades, multiple randomized clinical trials in preterm infants have been performed to evaluate the effect of probiotic administration on NEC prevention. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 2. A total of 10520 infants have now been enrolled in probiotic-NEC studies, and a cumulative pooled meta-analysis of the effects of probiotics on NEC was recently published[19]. In these trials, a wide variety of probiotic strains,dosages, and durations were used. Despite the clinical heterogeneity, the conclusion of the cumulative meta-analysis was that probiotic treatment decreased the incidence of NEC (average estimate of treatment effect, relative risk: 0.53; 95%CI: 0.42-0.66)[19].Therefore, it is clear that some oral probiotics can prevent NEC and decrease mortality in preterm infants. However, it is unclear whether a single probiotic or a mixture of probiotics is most effective for the prevention of NEC. Furthermore, some questions remain unanswered regarding the quality of probiotic products, safety, optimal dosage, and treatment duration.

Probiotics are not all equally effective in preventing NEC in preterm infants. Avariety of probiotic strains have been tested in different trials. A detailed analysis of the published data on the effects of probiotics for preterm infant regarding specific probiotic strains was recently performed by the ESPGHAN Working Group on Probiotics, Prebiotics and Committee on Nutrition[20]. They concluded that both Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12/B94 appeared to be effective in reducing NEC. Both the combination of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG with Bifidobacterium longum BB536 and the combination of Bifidobacterium lactis Bb-12 with Bifidobacterium longum BB536, however, showed no measurable effect. They suggest that we need to more precisely define the optimal treatment strategies before the routine clinical use of probiotics in preterm infants for NEC prevention can be recommended. Another recent meta-analysis concluded that multiple strains of probiotics were associated with a significantly lower incidence of NEC, with a pooled OR of 0.36 (95%CI: 0.24-0.53; P < 0.00001)[21]. As probiotics are neither drugs nor devices, they fall into a peculiar category of medical intervention and are therefore not strictly regulated. Because the cost of probiotics is low and the consequences of NEC can be devastating, given the available evidence and safety profile of probiotics from the large number of infants studied, a strong argument can be made for the routine use of probiotics in all preterm infants during their NICU stay[22]. By offering donor milk to infants at high risk when no maternal milk was available, along with the routine use of probiotics, no confirmed NEC cases were reported in a NICU in Canada for over a year[22]. A much lower incidence of NEC was also observed in Japan where the use of probiotics in preterm infants was routine[23]. Based upon this strong evidence, Dr. Taylor[22]argues that NEC can be easily prevented by the routine use of human milk and prophylactic probiotics.

Table 1 Summary of five randomized controlled trials of human milk feeding on the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis

In fact, a large number of commercially available probiotic preparations have been used in different clinical settings. However, all of these products have not been approved as prescription medications through routine vigorous rules and regulations.Concerns regarding the quality of probiotics and the risk of probiotic-associated sepsis have been raised. For example, an increased incidence of NEC associated with routine administration of a particular probiotic preparation, Infloran™, in extremely preterm infants was recently reported[24]. In this observational study, the routine use of probiotics was implemented in 2008 in one NICU. Infants born at < 28 wk gestational age were prospectively followed and compared with historical controls.Routine use of Infloran™ in infants was associated with an increase in stage II or higher NEC (13.3% vs 5.9%, P = 0.010). Surgical NEC was 12.1% vs 5.9% (P = 0.029).Adjusting for confounders (sex, gestational age, antenatal steroids and human milk)did not change those trends (P = 0.019). Therefore, some experts propose that if an NICU plans to pursue the use of probiotics as a routine supplementation for preterm infants, a quality improvement approach should be utilized to measure the desired effect of probiotics on the risk of NEC and to assess their safety[19].

RESTRICT EMPIRIC ANTIBIOTIC USE

Empiric antibiotics are commonly used in preterm infants immediately after birth due to the possibility that infection caused preterm labor and the relatively high risk for sepsis in VLBW infants. Because the presence of bacteria is one of the main risk factorsfor NEC, some believe that the use of prophylactic antibiotics may decrease the risk of NEC. Others feel that the opposite is true and that the altered normal postnatal gut colonization due to antibiotic use may contribute to the pathogenesis of NEC[17].Several randomized controlled clinical trials have been performed to evaluate the effect of prophylactic antibiotic administration on the risk of NEC. The results of randomized controlled trials are summarized in Table 3[47-51]. Although Siu et al[50]found that prophylactic oral vancomycin conferred some protection against NEC in VLBW infants, Tagare et al[47], Kenyon et al[48]and Owen et al[51]found no protective effect of routine antibiotic use in low risk preterm neonates. Rather, their data suggest that antibiotic may increase the risk of NEC. The efficacy of prophylactic antibiotic usage in the prevention of NEC in premature infants was reviewed, and a metaanalysis on this topic was recently published[52]. Only randomized controlled trials or retrospective cohort studies in LBW infants or preterm infants were included in the meta-analysis. As a result, a total of 5207 infants were included in nine studies. Based on their meta-analysis, the authors conclude that the current evidence does not support the use of prophylactic antibiotics to reduce the incidence of NEC for highrisk premature infants[52].

Table 2 Summary of 23 randomized controlled trials of probiotics on the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis

BW: Birth weight; LOS: Late onset sepsis; NEC: Necrotizing enterocolitis.

On the other hand, restricting the use of initial empiric antibiotics course may be important. There is increasing recognition that prolonged empirical antibiotic use might increase the risk of NEC for high-risk premature infants. Cotton et al[53]investigated initial empirical antibiotic practices for 4039 extremely low birth weight(ELBW) infants, and 2147 infants in the study cohort received initial empirical antibiotic treatment for more than 5 d. The data suggest that the administration of empiric antibiotics for more than 4 d when the blood culture is negative increases odds of NEC or death in ELBW infants. They suggest that prolonged initial empirical antibiotic therapy for infants with sterile cultures may be associated with increased risk of subsequent death or NEC and should be used with caution. In another retrospective 2:1 control-case analysis from Yale, 124 cases of NEC were matched with 248 controls. Infants with NEC were less likely to have had respiratory distress syndrome (P = 0.018) and more likely to have achieved full enteral feeding (P = 0.028)than were the controls. The risk of NEC significantly increased with duration of antibiotic exposure when infants with culture-confirmed sepsis were removed from the cohort, and exposure to antibiotics for more than 10 d resulted in an approximately three-fold increase in NEC risk[54].

Table 3 Summary of five randomized controlled trials of prophylactic antibiotics on the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis

STANDARDIZED FEEDING PROTOCOL

A current challenge in clinical NEC research is the high variation in feeding practices.It is clear that consistency in approach to feeding intolerance, feeding advancement and breast milk promotion all impact NEC. SFPs address a consistent approach to the:(1) preferred feeding substance; (2) advancement and fortification of feeding; (3)criteria to stop and specifying how to re-start feedings once held; (4) identification and handling of feeding intolerance; and (5) initiation and duration of trophic feeding.SFPs are simple, inexpensive, effective, and transmissible methods for prevention of postnatal growth restriction in premature infants.

In 2015, a total of 482 infants were enrolled in a feeding bundle study, which was a prospective quality improvement project to standardize a protocol for initiating and advancing enteral feeds, and to improve the nutritional care of neonates admitted to the NICU[55]. In this study, the feeding bundle included breast milk feeding, initiating feedings within 24 h of birth, fortification of breast milk with additional calcium,phosphorus and vitamin D, and the use of trophic feeding for 5 d for ELBW infants followed by daily increases of 10 to 20 mL/kg per day if criteria for tolerance are met.The rate of NEC after bundle implementation was decreased compared to the baseline rate of NEC prior to bundle implementation. Therefore, the authors suggest that early initiation and advancement of enteral feedings does not increase NEC risk, but may actually improve the outcomes[55]. In 2016, Gephart et al[14]reviewed papers published and found that studies consistently showed lower or unchanged NEC rates when SFPs were used. They combined data from nine observational studies of infants with birth weight < 1500 g and showed overall reduced odds of NEC by 67% (OR = 0.33,95%CI: 0.17, 0.65, P = 0.001) when SFPs were used. Therefore, it is possible that SFPs reduce the risk of NEC.

CONCLUSION

In this review, we summarize the results of the recent clinical trials and meta-analyses that support some of the common clinical practices to reduce the risk of NEC in premature infants. Firstly, it is evident that human milk feeding can reduce the incidence of NEC. We suggest enhanced lactation support in all NICUs, as well as the establishment of more human milk banks in NICUs. Secondly, while most of the studies demonstrated that probiotic supplementation can significantly reduce the incidence of NEC in premature infants, there are still some concerns in regards to the quality of probiotic preparations, safety, optimal dosage, and treatment duration.Thirdly, antibiotic prophylaxis does not reduce the incidence of NEC, and prolonged empirical use of antibiotics may in fact increase the risk of NEC for high-risk premature infants. Therefore, restricting initial empiric antibiotic use should be implemented in daily practice. Lastly, SFPs are recommended both for prevention of postnatal growth restriction and NEC.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Dr. Robert Green for critical review of the manuscript.