Guarding a Legacy

2019-04-18ByJiJing

By Ji Jing

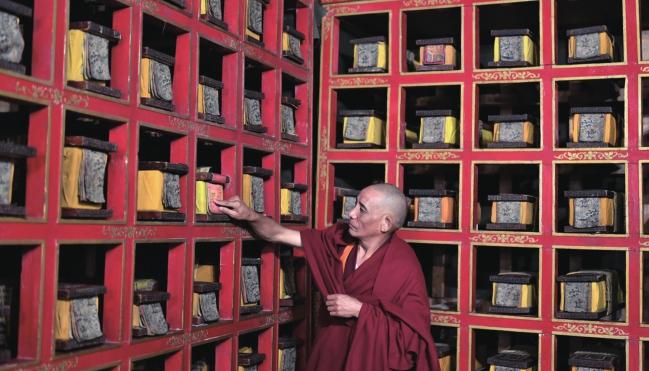

In a hall of the Potala Palace, a treasure trove of Tibetan history and culture in Lhasa, capital of Tibet Autonomous Region in southwest China, a 7-meter high book shelf is stacked with priceless ancient documents, including one written in the 17th century.

Documents are part of the amazing collections in the palace and have survived hundreds of years. In recent years, they became better protected as the palace upgraded its fi re-fi ghting facilities. However, dust, mice and natural aging still remain grave problems that need to be addressed urgently.

Now theres good news for conservationists and culture lovers. Over the next 10 years, the Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage will run a project for preventive protection, repair, protection through digitalization and display of the documents. The project will also inventorize the documents, recording their exact number and content. The government has allotted 300 million yuan ($44.8 million) for the work, the administration office of the palace recently announced.

Leaves from history

The documents include Buddhist scriptures and books on medicine, history and drama written in multiple languages such as Mandarin, Tibetan, Manchu, Mongolian and Sanskrit.

One of the most precious documents is the pattra-leaf scriptures.

Pattra means leaf in Sanskrit and the text, carved on leaves with bamboo or iron styluses, is mostly in Sanskrit. Apart from Buddhist classics, they include literature, art, philosophy, medicine and astrological treatises and throw light on the culture and history of South and Central Asia. Experts estimate it is the largest collection of pattra-leaf scriptures worldwide.

To protect these invaluable relics, the palace built a warehouse equipped with surveillance cameras in 2009 exclusively to store them.

In recent years, efforts have been stepped up to preserving the documents as part of the cultural heritage protection drive worldwide. However, despite the progress in the work, the administration office has finished registering only 60 percent of the documents due to their vast number and the fact that they are kept in different areas of the palace.

Although some of the documents have been published, the content of many remains undivulged. The project will utilize modern technology, like digitalization, to allow visitors to explore their scanned versions.

A pearl on roof of the world

Located on the 3,700-meter-high Red Mountain in the heart of Lhasa, the Potala Palace was originally built in the seventh century by Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo (617-650).

It remained unchanged till the mid-17th century when Lhasa became the political, religious, cultural and economic center of Tibet and the Fifth Dalai Lama, the head of the local Tibetan Government, decided to rebuild the Potala Palace in 1645. It became an important venue where he lived, carried out religious activities and dealt with administrative affairs.

The palace has been expanded several times since then and listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in December 1994. The main building is 115.7 meters high.

It went through the first major renovation in 1989 when the Central Government spent over 53 million yuan ($14.13 million, at then exchange rate) and a huge amount of gold and silver to conduct 111 repairs.

The second major renovation took place in 2002 when over 200 million yuan ($29.8 million) was spent to repair 29 main buildings and 35 attached ones, a task that took seven years.

Every year, Potala Palace staff paint the exterior, including the walls, doors and windows. The task takes two months and must be complete before Buddhas Descent Day, when pilgrims swarm into the palace and pray for Buddhas descent from heaven on the 22nd day of the ninth month in Tibetan calendar. The painting practice has lasted over 300 years.

“The Potala Palace is like an elderly man who needs tender care,” Tashi Phuntsok, deputy director of the repair department of the palaces administration offi ce, told Xinhua News Agency.

The repair department has a team of 65 including seasoned masons, carpenters, bricklayers and tailors.

“Daily maintenance is an important way to … prevent more serious damage,” Phuntsok said.

Currently there are over 400 workers at the administration office. Over the past five years, the offi ce has registered over 14 categories of artifacts, recording their age, provenance and dimensions in both Tibetan and Mandarin. By the end of 2018, over 40,000 Buddha statues, 2,000 thangkas, traditional Tibetan paintings on silk, cotton or paper, and other artifacts had been digitally recorded.