Growth of Ordered ZnO Structures on Au(111) and Cu(111)

2018-12-20赵新飞,陈浩,吴昊等

Abstract: The growth and structural properties of ZnO thin films on both Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces were studied using either NO2 or O2 as oxidizing agent. The results indicate that NO2 promotes the formation of well-ordered ZnO thin films on both Au(111) and Cu(111).The stoichiometric ZnO thin films obtained on these two surfaces exhibit a flattened and non-polar ZnO(0001) structure. It is shown that on Au(111), the growth of bilayer ZnO nanostructures (NSs) is favored during the deposition of Zn in presence of NO2 at 300 K, whereas both monolayer and bilayer ZnO NSs could be observed when Zn is deposited at elevated temperatures under a NO2 atmosphere. The growth of bilayer ZnO NSs is caused by the stronger interaction between two ZnO layers than between ZnO and Au(111) surface. In contrast, the growth of monolayer ZnO NSs involves a kinetically controlled process. ZnO thin films covering the Au(111) surface exhibits a multilayer thickness, which is consistent with the growth kinetics of ZnO NSs. Besides, the use of O2 as oxidizing agent could lead to the formation of substoichiometric ZnOx structures. The growth of full layers of ZnO on Cu(111) has been a difficult task, mainly because of the interdiffusion of Zn promoted by the strong interaction between Cu and Zn and the formation of Cu surface oxides by the oxidation of Cu(111). We overcome this problem by using NO2 as oxidizing agent to form well-ordered ZnO thin films covering the Cu(111)surface. The surface of the well-ordered ZnO thin films on Cu(111) displays mainly a moiré pattern, which suggests a (3 × 3) ZnO superlattice supported on a (4 × 4) supercell of Cu(111). The observation of this superstructure provides a direct experimental evidence for the recently proposed structural model of ZnO on Cu(111), which suggests that this superstructure exhibits the minimal strain. Our studies suggested that the surface structures of ZnO thin films could change depending on the oxidation level or the oxidant used. The oxidation of Cu(111) could also become a key factor for the growth of ZnO. When Cu(111) is pre-oxidized to form copper surface oxides, the growth mode of ZnOx is altered and single-site Zn could be confined into the lattice of copper surface oxides. Our studies show that the growth of ZnO is promoted by inhibiting the diffusion of Zn into metal substrates and preventing the formation of sub-stoichiometric ZnOx. In short, the use of an atomic oxygen source is advantageous to the growth of ZnO thin films on Au(111) and Cu(111) surfaces.

Key Words: ZnO/Au(111); ZnO/Cu(111); STM; XPS; Model catalysis

1 Introduction

ZnO-based catalysts are widely used in the conversion of small energy molecules, including reactions such as the methanol synthesis1, water-gas-shift (WGS) reaction2,3and more recently the selective conversion of syngas to light olefins4.Despite its tremendous importance, model catalytic studies on the well-defined ZnO surfaces have been limited5,6, which in part could be attributed to the difficulties in preparing and characterizing the atomic structures of ZnO single crystals, not to mention that Zn is volatile and could contaminate the ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) chamber. In the past decades, efforts have been dedicated to the synthesis of well-defined ZnO thin films on the surfaces of metal single crystals7. As a result, ZnO layers have been grown on different metals, such as Pd(111)8,Pt(111)9,10, Au(111)11–13, Ag(111)5,14, Cu(111)15and Brass16.These studies have shown both theoretically and experimentally that ZnO thin layers on metal substrates would transform from the wurtzite structure of bulk ZnO to a two-dimensional (2D)stable honeycomb structure similar to that of graphene or h-BN.The series of growth studies also show that the structures or super-structures of the graphene-like zinc oxide (g-ZnO) could be dependent on the metal substrates.

Typically, well-defined metal oxide thin layers were prepared on metal single crystals via a vapor deposition process either in UHV, which is followed by an oxidation process, or in an O2atmosphere, i.e. the so-called reactive evaporation process17.Among the growth of metal oxide thin films, the control over the growth of ZnO thin films has been relatively poor, such that a variety of (super)structures and thickness have been reported to co-exist at the surface. One possible reason is that O2is not a good oxidation agent for the growth of ZnO under UHV conditions. For instance, the growth of ZnO on Au(111) has shown ZnO islands exhibit a variety of island thickness,depending on the oxygen chemical potential and the annealing temperatures. The growth of well-ordered ZnO thin films on Cu(111) has been particularly difficult for current experimental studies, which lack structural details and have not reached a consensus on the growth recipe. This has made the model catalytic studies on ZnO/Cu(111) or the ZnO-Cu interface a challenging task.

ZnO thin layers on Cu(111) is a model system of tremendous interest in current catalysis research. The Cu-ZnO composite catalysts, often supported on alumina, were generally used for the industrial processes of WGS and methanol synthesis. Despite decades of research, basic questions such as the active phase of the Cu-ZnO catalyst remain unclear and nowadays in heavy debate18–21. Lunkenbein et al.19reported the formation of“graphite-like” ZnO layers on Cu during the reductive activation of the Cu/ZnO catalysts, which might lead to a synergistic effect in the Cu/ZnO/Al2O3catalysts for methanol synthesis. Kattel et al.21confirmed the synergy of Cu and ZnO at the interface in facilitating methanol synthesis by studying a few model surfaces. On the contrary, Kuld et al.18quantified Zn atoms in the Zn-Cu alloy and suggested that the increase of surface Zn coverage enhances the methanol synthesis activity. The lack of structural understanding on the ZnO layers on Cu has caused uncertainties in the discussion and calculations of catalytically active sites.

Hereby, we studied the growth of ZnO structures on Au(111)and Cu(111) using scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). We compared the effects of O2and NO2for the growth of ZnO layers on Au(111)and Cu(111). We found that the growth modes and structures of ZnO could vary with the oxidizing agents, as well as the preparation conditions, owing to the different oxidation and alloying capabilities of Zn and the metal substrates.

2 Experimental

The experiments were carried out in two combined UHV systems. One is equipped with near-ambient-pressure (NAP)STM (SPECS, Germany), mass spectroscopy (HIDEN, United Kingdom) and cleaning facilities. The other is equipped with NAP XPS (SPECS, Germany), mass spectroscopy (HIDEN,United Kingdom) and cleaning facilities. The base pressure of the STM chamber is < 2 × 10-10mbar (1 mbar = 100 Pa). The Au(111) and Cu(111) single crystals (HF-Kejing, China) were cleaned by cycles of Ar (> 99.9999%, Arkonic) ion sputtering and annealing at 700–800 K in 5 × 10-7mbar O2(> 99.9999%,Arkonic) and UHV. Au(111) and Cu(111) were subsequently checked by STM to confirm that the surface is clean and flat. Zn was evaporated in an O2or NO2(> 99.5%) environment onto the metal surfaces, with the metal substrates held at 300 K or elevated temperatures indicated in the text. STM images were taken in UHV at room temperature and processed with SPIP software (Imagemet, Denmark).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Growth of ZnO on Au(111)

Well-defined oxide thin films on metal substrates were traditionally prepared via the evaporation of metal atoms in an O2atmosphere. However, late transition metal surfaces with closed d shell exhibit low sticking coefficients for the dissociative adsorption of O2and thus requires large exposures of O2to saturate the metal surface with atomic oxygen. In this case, NO2serves as an excellent atomic oxygen source, which has a high dissociative sticking coefficient on the above metal surfaces22. The decomposition reaction of NO2(NO2→ NO +O) could provide clean atomic oxygen at 300 K on metal surfaces, while NO would desorb from the surface at 300 K22.Therefore, we compared the growth of ZnO on Au(111) using NO2or O2as the oxidation agents.

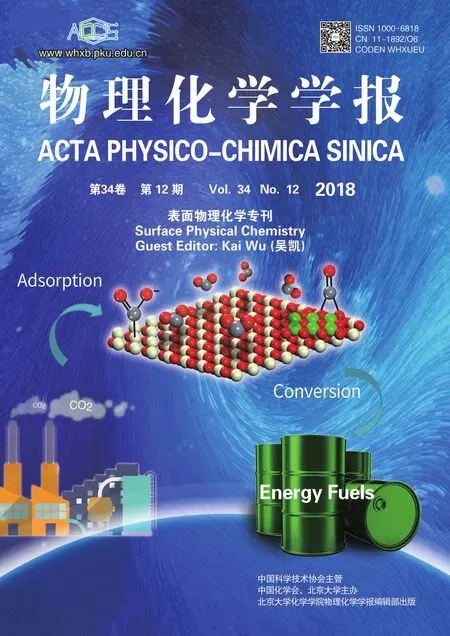

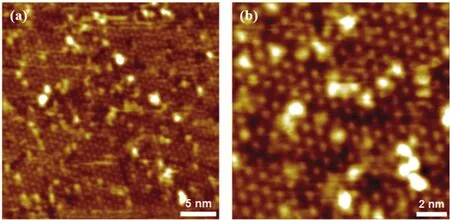

Fig. 1 The growth of ZnO nanostructures (NSs) on Au(111) in NO2.

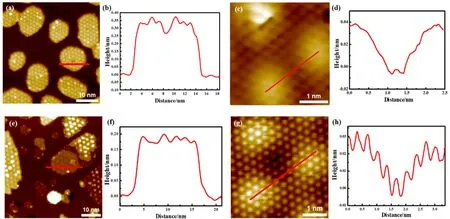

With NO2as the oxidation agent, well-defined ZnO nanostructures (NSs) or thin films could be grown on Au(111).When Zn was evaporated in 1 × 10-7mbar NO2onto Au(111) at 300 K, ZnO NSs of uniform apparent heights could be observed after the subsequent annealing at ~600 K (Fig. 1a). These ZnO NSs display a large moiré pattern of ~ 23 Å (1 Å = 0.1 nm) and exhibit a hexagonal lattice with the lattice spacing at ~3.3 Å (Fig.1c, d). In accordance with previous studies, ZnO NSs on Au(111) exhibit the surface lattice close to the (0001) facet of the wurtzite ZnO, which becomes flattened into a graphene-like surface. Compared with ZnO(0001), which has a lattice constant of 3.25 Å, the surface lattice of ZnO NSs has expanded slightly owing to the surface flattening. From the periodicity of the moiré lattice, the coincidence lattice should consist of a (7 × 7)-ZnO slab on a (8 × 8)-Au(111) slab, as also proposed in previous studies. The structural model of the moiré lattice is depicted in Fig. 2, showing the lattice of ZnO is well aligned with the major index of Au(111). The measured apparent height of these ZnO NSs is ~3.3–3.5 Å (Fig. 1b), which corresponds to the height of a bilayer (BL) ZnO NS.

When Zn was evaporated in 1 × 10-7mbar NO2at elevated temperatures, ZnO NSs of different layer thickness could be observed on Au(111). Fig. 1e shows a typical surface of ZnO NSs grown on Au(111) at ~450 K. ZnO NSs of both monolayer(ML) and BL thickness could be observed and their structures were compared in Figs. 1 and 2. ML ZnO NSs exhibit the moiré pattern and the atomic lattice same as those of BL ZnO NSs.However, we could not grow a surface with only ML ZnO NSs using NO2as the oxidation agent. Previous DFT calculations11have suggested the formation of BL ZnO(0001) is thermodynamically favored because the binding between the two ZnO layers is about twice the interfacial adhesion energy between ZnO and Au(111). The apparent height of ML ZnO NSs is ~1.8–2.0 Å (Fig. 1f) and larger than the height differences between the second and the first ZnO layers, which also indicates a stronger interaction between the two ZnO layers (Fig. 2). We found further the growth of ML ZnO NS is favored when depositing at elevated temperatures, which suggests the growth of ML ZnO is a kinetically controlled process23,24. At elevated temperatures and with sufficient oxygen atoms on the surface,the diffusion of Zn is facilitated and promotes the formation of larger ZnO nucleus and then islands. From the Gibbs-Thompson relationship25,26, the surface energy of nanoislands decreases with the increasing size. Thus, the formation of larger islands helps stabilizing the ML ZnO NSs and inhibit their transition to BL ZnO NSs.

Fig. 2 The structural models of ZnO structures on Au(111).

As we continued to grow the ZnO film covering up Au(111),we found that ZnO films are of multi-layer thickness when Au(111) was fully covered (Fig. 3). This is consistent with the preferential growth of BL ZnO NSs, owing to the stronger interaction between ZnO layers than that between ZnO and Au(111). Again, each layer of the ZnO films is well-ordered after the annealing, showing the same moiré pattern with a spacing at~23 Å. The atomic lattice of ZnO films is resolved in Fig. 3b,which displays a hexagonal lattice with the lattice spacing at~3.3 Å. Deng et al.11–13have also studied the growth of ZnO on Au(111) combining STM, XPS and DFT calculations and suggested that both BL ZnO and multilayer ZnO islands are present at the surface at 0.9 MLE ZnO coverage, which is in accordance with the multi-layer growth mode observed in our film growth. Their XPS results also showed the ratio of Zn:O as 1 : 1. Likewise, we observed the formation of stoichiometric ZnO on Au(111), showing a planar hexagonal surface lattice.

Fig. 3 The growth of ZnO thin films and ZnOx islands on Au(111).

When Zn was evaporated in 2 × 10-6mbar O2onto Au(111)at 300 K, we did not observe the formation of well-defined ZnO NSs even after the annealing at elevated temperatures and in O2.Fig. 3c shows that, accompanying the deposition of Zn in O2, the surface herringbones of Au(111) have disappeared, indicating the possible inter-diffusion of Zn and the formation of Zn-Au surface alloy27. Meanwhile, the apparent height of the deposited islands is ~3 Å, indicating the formation of ZnOxrather than metallic islands, because Au(111) gave a step height at ~2.4 Å.Yet, these ZnOxstructures might not be well-ordered and we did not achieve atomic resolution on these island surfaces. ZnOxislands grown by O2also exhibit lower thermal stability than the well-ordered ZnO NSs. We found sub-stoichiometric ZnOxislands could decompose upon the annealing to 550 K in UHV,whereas well-defined ML or BL ZnO NSs would remain stable on Au(111) at this temperature. Note that, well-ordered ZnO NSs could also be formed by depositing Zn in UHV, which is followed by the annealing in 5 × 10-7mbar NO2. Therefore, the supply of atomic oxygen is key to the growth of well-defined ZnO thin layers on Au(111), since both Zn and Au show weak interaction with O2under UHV conditions.

3.2 Growth of ZnO on Cu(111)

With the knowledge obtained from the growth of ZnO on Au(111), we studied further the growth of ZnO on Cu(111). The growth of well-defined ZnO thin films on Cu(111) has been a challenging task, according to the literature. Sano et al.28studied earlier the oxidation of a Zn-deposited Cu(111) surface. They found the strong interaction between Cu and Zn leads to the formation of Cu-Zn surface alloy and the oxidation by excess exposure of O2could only lead to the formation of alternating stripes of Cu2O and ZnO at high temperatures. The formed ZnO islands were rotated with respect to the Cu(111) substrate and the ZnO surface exhibits a unit cell vector of 4.8 Å. Liu et al.15reported recently, using also O2as the oxidation agent to grow ZnO thin films on Cu(111). They found the formation of ordered ZnO thin films is dependent on the heating rate. The ZnO overlayer covering the entire surface of Cu(111) could not be achieved even with step-wise heating in O2.

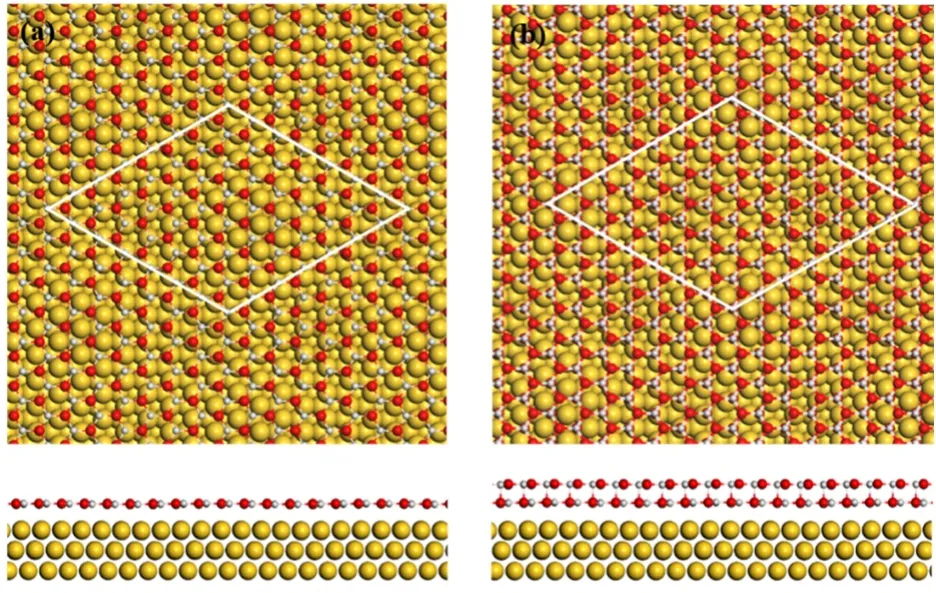

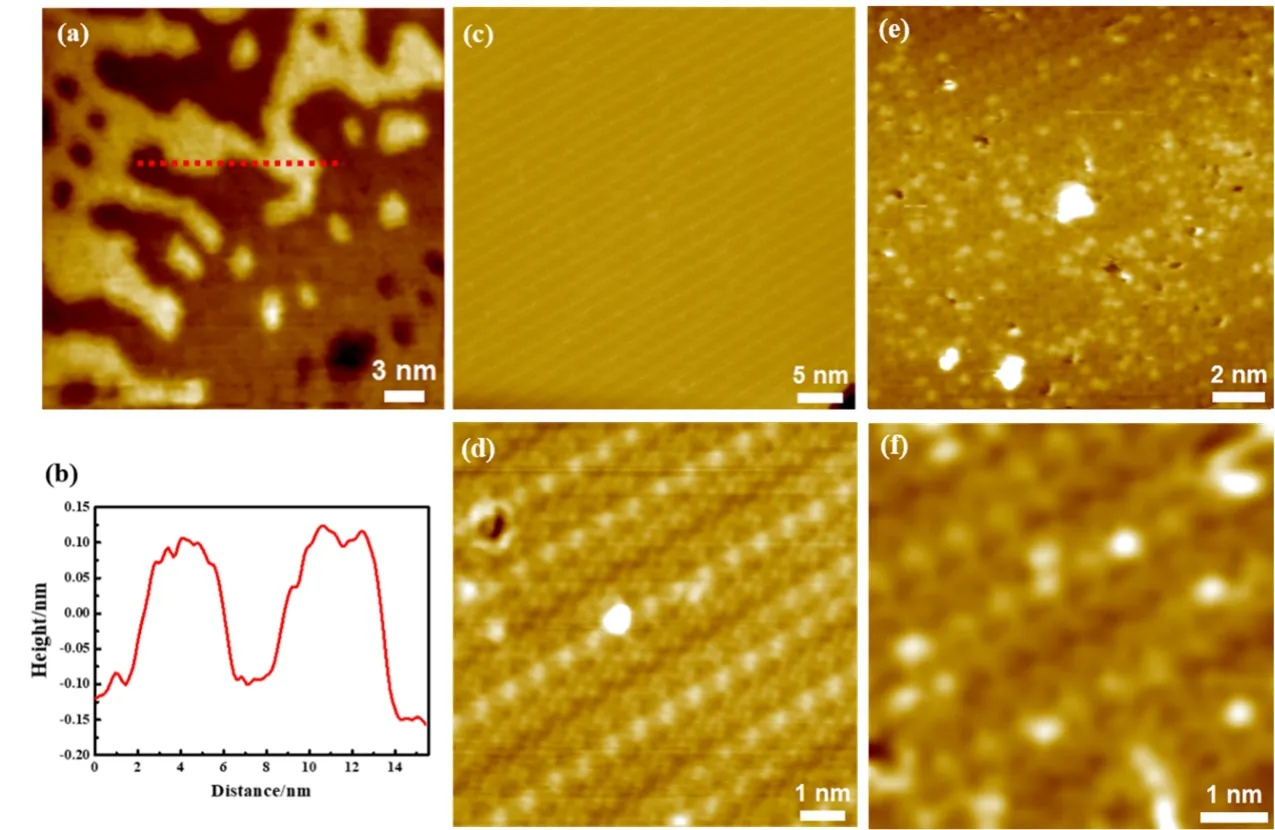

Hereby, we attempted the growth of ZnO thin films on Cu(111) using NO2or O2as the oxidation agent. We show first the growth of well-ordered ZnO oxide films covering the surface of Cu(111) is possible with NO2. By evaporating Zn in 1 × 10-7mbar NO2onto Cu(111), Fig. 4a shows the surface of flat ZnO layers after the annealing in 5 × 10-8mbar NO2at ~500 K. The corrugated film surface displays a hexagonal superlattice with a periodicity of ~10 Å (Fig. 4b). Since the surface oxides of Cu(111), either ‘44’ or ‘29’ structures29,30, exhibit the stripe-like structures and parallelogram lattices, the formed hexagonal lattice should not be assigned to copper oxides, but rather the formation of ZnO thin films. Given the lattice constant of ZnO at 3.25 Å, the observed surface pattern (Fig. 4b) suggested a moiré lattice between ZnO and Cu(111), i.e. the coincidence lattice of a (3 × 3)-ZnO slab on a (4 × 4)-Cu(111) slab (Fig. 4c).

Previous DFT calculations31have suggested the coincidence lattice of a (4 × 4)-ZnO supercell on a (5 × 5)-Cu(111) substrate,which was also supported by the recent study of Liu et al.15However, Tosoni et al.32have shown recently in their calculations that, though with negative strain, a (3 × 3) ZnO superlattice supported on a (4 × 4) supercell of Cu(111) gives the most stable structure with the minimal strain. Our study thus provided the direct proof for the proposed most stable structure of ZnO on Cu(111). On the other hand, the structural difference with the study by Liu et al.15suggested the possible influence of oxidation agents and that the use of NO2is advantageous to achieve the energetically favored ZnO structure on Cu(111).

Fig. 4 The growth of ZnO thin films on Cu(111).

The ZnO film on Cu(111) is not uniform as the case of ZnO films on Au(111). Fig. 4a and 4d show also relatively flat areas of the ZnO film without the corrugated moiré pattern. High resolution STM shows these areas could exhibit another type of surface lattice with the spacing of ~5.5 Å (Fig. 4e). Note that,this surface lattice is rotated by ~30° with respect to the main superlattice observed in Fig. 4b. When we rotate the ZnO lattice against the major index of Cu(111) by 30°, we could find indeed a supercell with the periodicity ~5.5 Å (Fig. 4f). We could rule out other structural possibilities such as a metallic or alloy surface, since Sano et al.28have shown the Cu-Zn alloy surface gives an atomic lattice of ~2.5 Å. The formation of copper oxides could also be excluded since they form stripe structures. Another possibility regarding the formation of the copper oxide interfaces or buried interfacial layers could also be ruled out by XPS measurements. Fig. 5 shows that the preparation of ZnO thin films on Cu(111) did not result in oxidation peaks in either Cu 2p or Cu LMM spectra. Thus, the above growth recipe could be potentially used to grow ZnO thin films covering up the Cu(111)surface. The thickness of the as-grown ZnO thin films is not clear. But previous studies16,32have suggested a BL layer growth mode and ZnO thin films on Cu(111) have been shown as a “self-limited” growth by Liu et al.15The structural parameters of ZnO thin films on Cu(111) reported in the literature have been ranging from 4.8 to 13.5 Å. The inability to reach a consensus is probably caused the differences in the growth recipe and the usage of O2.

Fig. 5 XPS spectra of ZnO thin films on Cu(111).

The supply of oxygen atoms seems to be a key factor in determining the structure of ZnO, as well as its registry on Cu(111). Certainly, a major concern is no atomic lattice of ZnO has been resolved on Cu(111) so far, which leaves the uncertainty whether the various (super)structures reported in the literature are from the different structures, corresponding to the different stoichiometries of ZnOx, or caused by different registries of ZnO on Cu(111). While the later possibility was usually cited to explain the respective structure of ZnO on Cu(111), the former explanation could also be the case since O2could not supply active oxygen atoms sufficient for the full oxidation of Zn atoms at low temperatures. Meanwhile, ZnO on Pt(111) has also displayed varied structures dependent on the O chemical potential. Thus, in order to achieve an ordered and stoichiometric ZnO film on Cu(111), NO2is a preferred oxidation agent. The ZnO film shown in Fig. 4 is expected to be stoichiometric, since a similar recipe has been able to produce a stoichiometric ZnO thin films on Au(111), which shows much weaker binding for oxygen than Cu(111).

When Zn was evaporated onto Cu(111) in 2 × 10-5mbar O2,which is followed by the annealing in 5 × 10-8mbar NO2at ~600 K, we could also observe the formation of a flat oxide film on Cu(111). Fig. 6 shows the periodicity of the film is also ~10 Å,same as the ZnO film described above. There are some bright clusters decorated on the surface of ZnO, which could be attributed to the incomplete surface oxidation process and the formation of sub-stoichiometric ZnOxstructures. Liu et al.15have also reported the de-wetting of ZnO films on Cu(111) upon the annealing in UHV at above 600 K.

Fig. 6 STM images of the ZnO thin films prepared by depositing Zn atoms in 2×10-5 mbar O2 onto Cu(111), which is followed by annealing in 5 × 10-8 mbar NO2 at ~600 K.

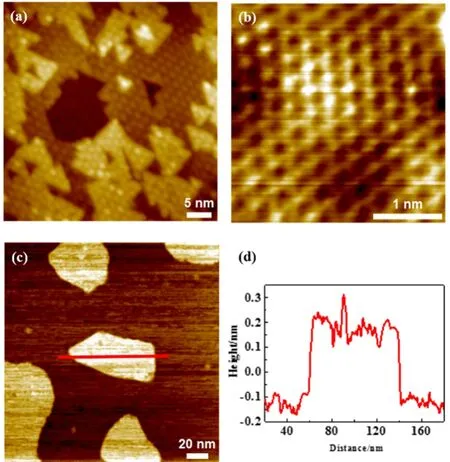

Fig. 7 The growth of ZnOx in O2 on Cu(111).

Note that, although previous studies5,15,28have used O2to prepare ZnO thin films on Cu(111) successfully, the preparation procedures are usually strict on the O2exposure, the annealing temperature and the heating rate. These requirements have very much to do with the instability of metallic Zn or substoichiometric ZnOxon Cu(111). Zn is volatile and could evaporate at below 500 K in UHV. Meanwhile, Zn also interacts strongly with Cu(111) and could form Zn-Cu surface alloy at even 300 K15. The formation of ZnOxcould increase the stability of Zn on the surface of Cu(111). However, prior to the formation of stoichiometric ZnO, ZnOxis not stable upon thermal annealing in UHV, which has been shown in the growth of ZnO on Au(111) using O2(Fig. 3). On Cu(111), when Zn was evaporated in 2 × 10-6mbar O2for 15 seconds at 300 K, we found islands on Cu(111) with a step height of ~2.0–2.4 Å (Fig.7a, b), which could be attributed to metallic islands or substoichiometric ZnOx. In such short time, the initiation of surface oxidation of Cu(111) was also not obvious. Upon further oxidation in 2 × 10-5mbar O2at ~550 K, we observe indeed the formation of complex copper surface oxides, showing stripe structures (Fig. 7c, d). Thus, in contrast to previous studies which use excess O2and step-wise heating to prepare the ZnO films,the direct heating would destabilize Zn atoms at the surface,causing a faster inter-diffusion process into the Cu bulk or desorption from Cu(111). As a result, only ordered copper surface oxides were observed. There is another possibility that the formation of Cu2O surface oxide layers could alter the growth kinetics and subsequently change the structure of ZnOx.

Indeed, when Cu(111) was first oxidized in 2 × 10-5mbar O2at ~550 K, the subsequent Zn deposition in 2 × 10-5mbar O2would lead to the formation of highly dispersed Zn atoms/clusters at the copper oxide surface (Fig. 7e, f). The formation of dark holes on the copper oxide surface suggests that lattice oxygen atoms were scavenged by deposited Zn atoms to form ZnOxmotifs, since Zn binds stronger with oxygen than Cu does. The magnified STM image (Fig. 7f) shows that most zinc atoms were likely embedded into the lattice of copper surface oxide, since their apparent heights are less than 1 Å above the surface oxide plane. Owing to the stronger Zn―O bond over the Cu―O bond, the pre-existing surface oxide lattice provides a network for the formation of single-site Zn and confines Zn in the copper oxide lattice.

4 Conclusions

We have investigated the growth and structures of ZnO on Au(111) and Cu(111). In our study, O2as the oxidation agent cannot transform vapor deposited Zn atom into stoichiometric ZnO thin films on either Au(111) or Cu(111). Rather, using NO2,an atomic oxygen source, could facilitate the growth of welldefined ZnO films on both Au(111) and Cu(111). The formed ZnO thin layers are non-polar, similar to the (0001) facet of wurtzite ZnO, but become flattened and exhibit a graphene-like hexagonal lattice. On Au(111), the growth of BL ZnO NSs are preferred when Zn was deposited in NO2at 300 K. This is caused by the stronger interlayer bonding between ZnO layers over the interaction between ZnO and Au(111). In contrast, both ML and BL ZnO NSs could be observed when Zn was deposited in NO2at elevated temperatures. Consistently, the further growth of ZnO thin films covering up the Au(111) surface also exhibit the multilayer thickness.

On Cu(111), we found, with NO2as the oxidation agent, an ordered ZnO thin film could be prepared and cover up the Cu(111) surface. This overcomes the problems of incomplete ZnO layers neighbored with Cu2O/Cu surface domains, which were suffered in previous attempts using O2as the oxidant. The moiré lattice on ZnO layers suggested a (3 × 3) ZnO superlattice supported on a (4 × 4) supercell of Cu(111), which is consistent with the recent proposed structural model of ZnO on Cu(111),showing minimal strain. Another structure of (2 × 2)R30° ZnO domains could also be observed, but much less popular on the film surface. Our studies show the surface structures of ZnO could vary with the oxidation level or the oxidant used, which explained the varied structural parameters reported for ZnO on Cu(111). Meanwhile, the oxidation of the Cu(111) surface could also become a competing factor for the growth of ZnO. When the Cu(111) surface was pre-oxidized to form copper surface oxides, the subsequent deposition of Zn in O2would lead to the formation of single-site Zn embedded into the copper oxide lattice. Our studies thus suggested the use of atomic oxygen sources for the growth of well-ordered ZnO thin films. The atomic structure of ZnO on Cu(111) is dependent on the oxygen chemical potential and requires further investigation at the atomic scale.

Acknowledgement:We appreciate the assistances in the preparation of graphs from LIU Qingfei, ZHOU Zhiwen and LIN Le from Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

杂志排行

物理化学学报的其它文章

- Tree-Like NiS-Ni3S2/NF Heterostructure Array and Its Application in Oxygen Evolution Reaction

- CO Induced Single and Multiple Au Adatoms Trapped by Melem Self-Assembly

- Morphologies and Electronic Structures of Calcium-Doped Ceria Model Catalysts and Their Interaction with CO2

- In-situ APXPS and STM Study of the Activation of H2 on ZnO(1010)Surface

- Adsorption and Activation of O2 and CO on the Ni(111) Surface

- Atomic Layer Deposition: A Gas Phase Route to Bottom-up Precise Synthesis of Heterogeneous Catalyst