A review on the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS): history,development and application

2018-11-20PengTianTaoWangBaoHeWangJieLiQiangXuDengFengKongWeiMuYuHongHuang

Peng Tian, Tao Wang, Bao-He Wang, Jie Li, Qiang Xu, Deng-Feng Kong, Wei Mu ,Yu-Hong Huang

1Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China. 2Cardiovascular Disease Two Department,Second Affiliated Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China. 3Second Affiliated Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China. 4Clinical Pharmacology Department, Second Affiliated Hospital of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, China.

Background

With the development of the biological-psychological-social medical model, the concept of patient-centered care has been widely recognized and concerned since the 1960s [1-2].Evidence-based medicine and narrative medicine that came out at the beginning of the 21st century have promoted the development of patients’ participation in medical practice from different perspectives. Shared decision-making is considered as a key part of the“patient-centered” model, in which PtDA is used as a means to achieve common decision-making, helping patients to be prudent and in line with their own value on the basis of full informed consent. Research shows that PtDA could help improve patients’ health knowledge and expectations; increase participation in decision-making positivity; reduce decision-making conflicts; and increase the matching of values and choices [3, 5].

Study background of PtDA for international patients

Current research state of PtDA

With the development of shared decision-making,decision support technology has emerged as require,among which the most rapid development is the flexible PtDA. The application of PtDA can improve the patient’s health awareness and treatment compliance. The doctor can fully understand the patient’s preferences and thus develop a personalized treatment plan to improve the quality and effectiveness of decision-making. In the database of the Institute of Hospital Affiliation, University of Ottawa, 684 patient decision aids were registered and included [6]. The systematic review of PtDA published in the April 2017 issue of the Cochrane Library included 105 decision tools [4]. The National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence (NICE) has included 13 PtDA. Shared decision-making has been highly valued by government agencies and health systems in Europe and the United States. In 2007, Washington State passed the first informed consent legislation, which clearly stipulated that shared decision-making is a necessary for informed consent [7]. The legislation stipulates that shared decision-making includes the participation of patients in the decision-making process and the use of PtDA to help patients understand the disease and treatment plan. In Europe, shared decision-making has been widely promoted in the Netherlands, and the Spanish public health system has also shown its emphasis on shared decision-making [8-9].

Research purpose of PtDA

Many individuals and groups in the global medical and health field have developed a large number of PtDA,many of which have been put into use, and have promoted the development of clinical common decision-making. The development of the Internet and mobile technologies has also provided favorable opportunities and a good platform for their dissemination [10]. The tools developed in accordance with widely recognized quality standards are likely to provide reliable help to doctors and patients. However,due to the lag in the development of quality assessment standards, the quality of PtDA that have been developed so far has varied. Therefore, it is necessary to come into internationally uniform evaluation standards to ensure the scientific and reliability of PtDA.

Definition of PtDA

There is no globally unified definition of PtDA. Stacey,a leader in the field of shared decision-making,believes that PtDAs are interventions designed to help people make specific and deliberate choices by providing information on personal health-related choices and corresponding outcomes [4]. The International Patient Decision Assisted Quality Standards Consortium (later known as the Confederation) considered that PtDA designed to help people actively participate in health care choices. It provides current best health information based on evidence-based medicine and narrative medical research, which helping patients to clarify and communicate personal values related to different options and aiming to complement rather than replace the doctor’s advice [13]. The ultimate goal of PtDA is to improve the quality of clinical decision-making [14].High-quality decision-making means that the patient’s choice is made with full knowledge and is most consistent with his personal preference [15].

The development course of international PtDA

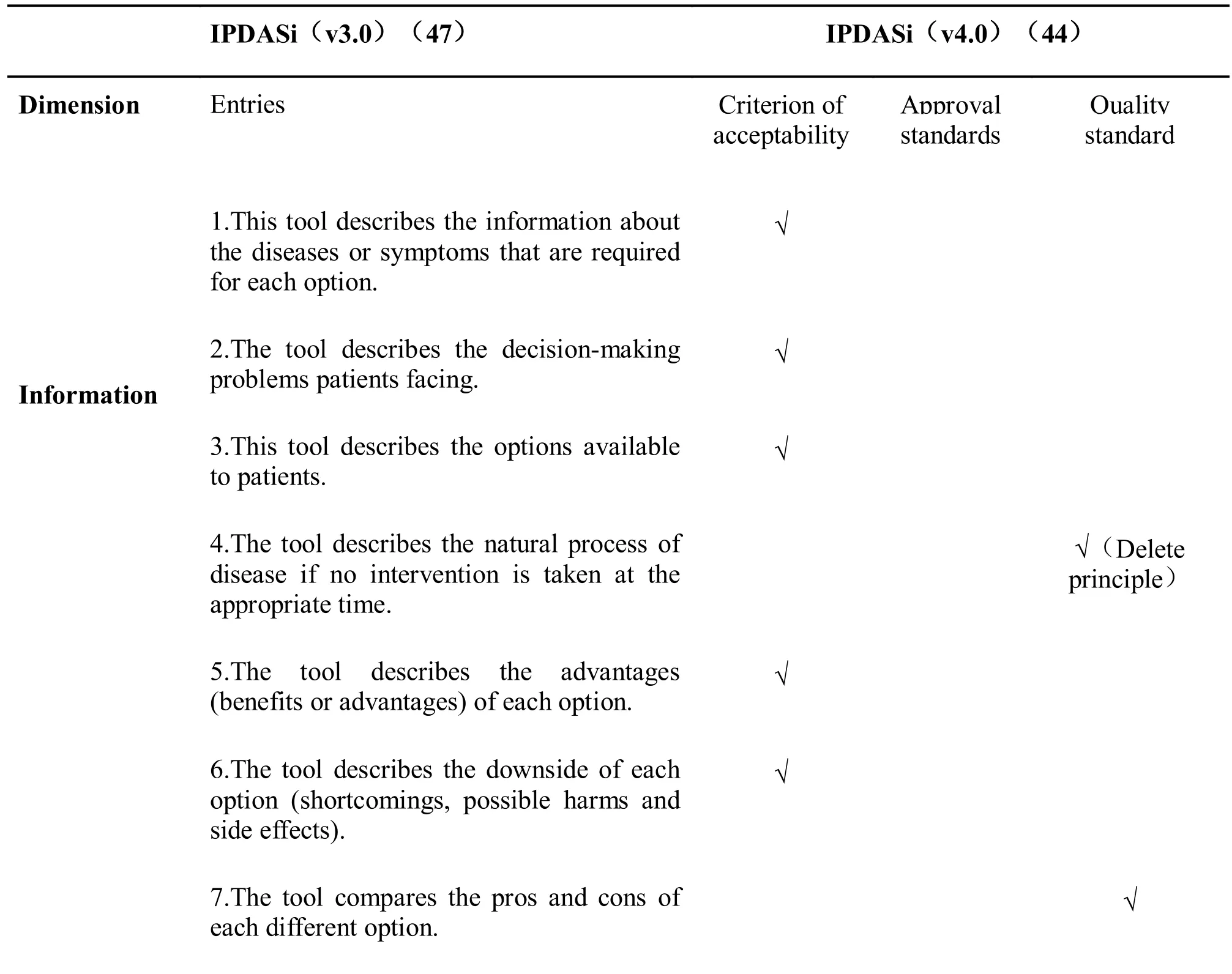

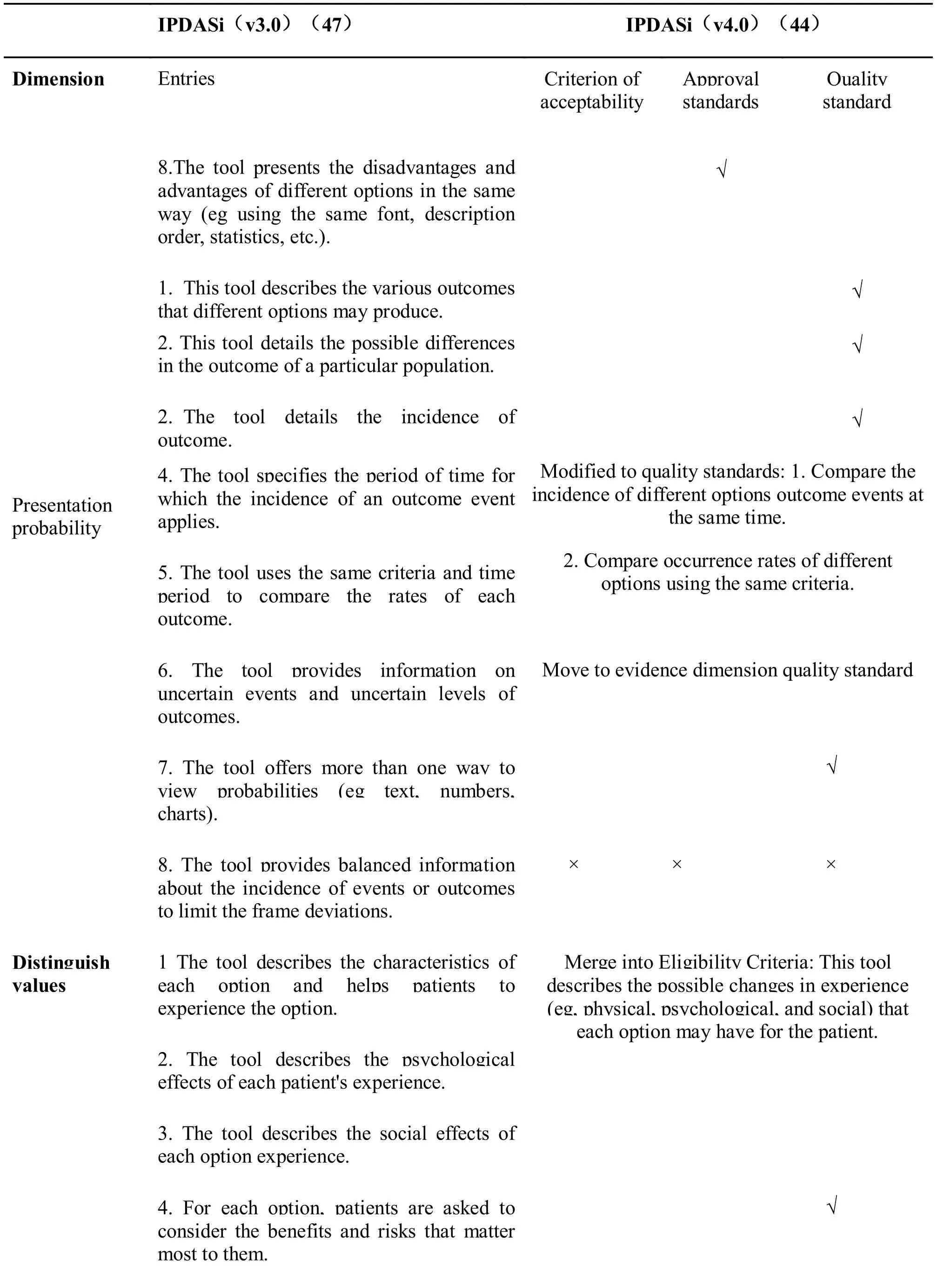

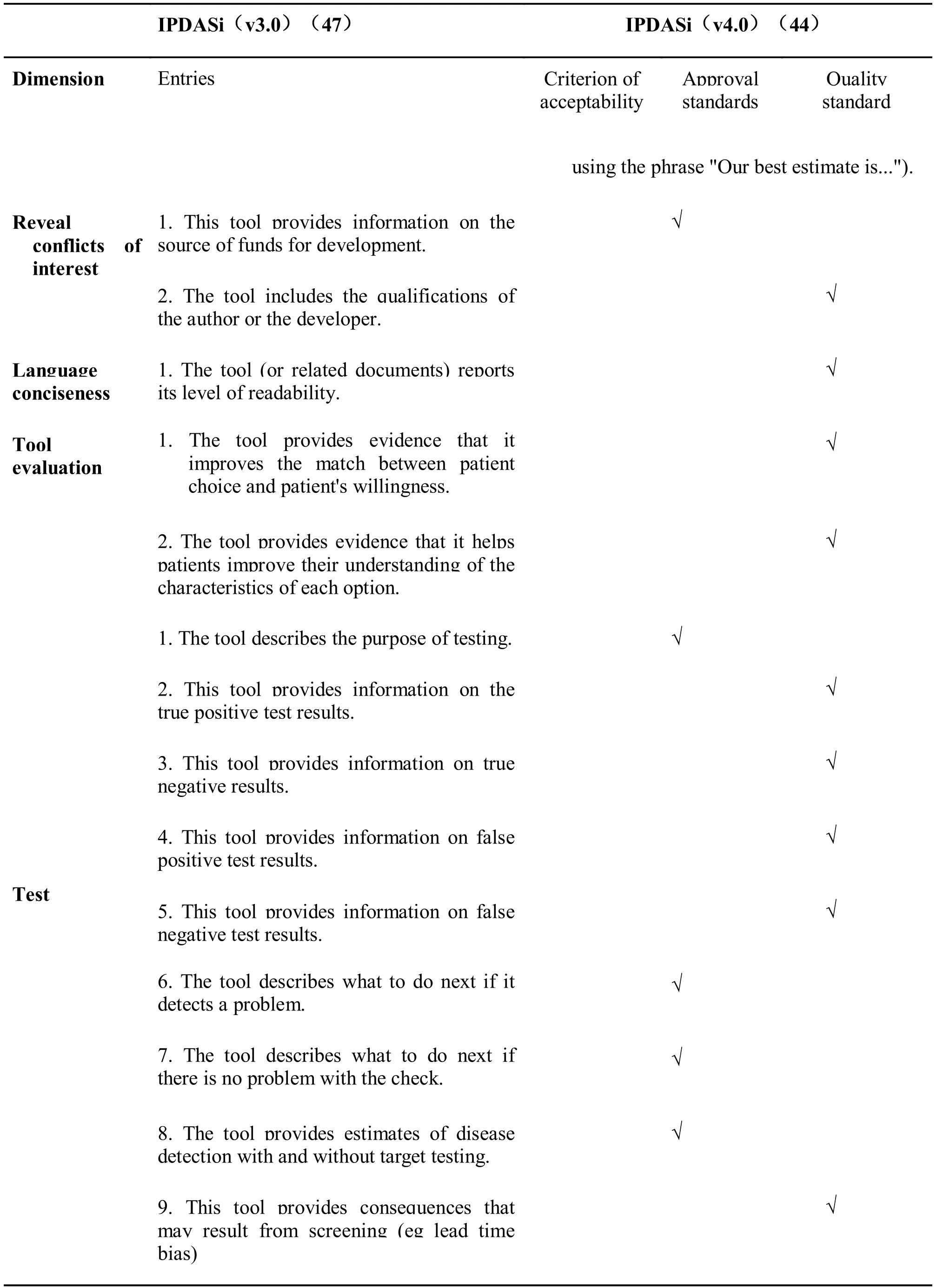

In 2003, the International Patient Decision Aid standards Collaboration was set up at the Second International Common Decision Making Conference,that establish a theoretical framework for shared decision-making based on evidence-based medicine to improve the quality and effectiveness of PtDA, and develop content, developing, implement and evaluating standards. In 2006, the Federation issued the IPDAS list. From then on, several versions of the IPDASi(International Patient Decision Aid Standards instrument) 1.0 to 4.0 were developed on the basis of the list. (See Table 1 for the development of IPDAS.)

In 2005, the federation reached a consensus on the quality evaluation of PtDA and established an internationally recognized standard framework. In 2005, the federation reached a consensus on the quality evaluation of PtDA and established an internationally recognized standard framework. List of IPDAs issued in 2006. The following is a brief introduction to the process of generating the following list. The federation adopted the delphi method to consult widely with stakeholders, patients, doctors, policy makers and potential users of PtDA from 14 countries, which was reached consensus after two rounds of voting [15-18].The IPDAS checklist is divided into three parts: the main content of PtDA, the development process, and the validity, including 12 quality dimensions and 74 items. In the first part, the main contents of the PtDA which include the information of target patients and diseases, the risk-benefit ratio, personal values, and the guidance of decision-making steps. The second part is the development process of PtDA. This section stipulates the relevant design and method technical standards, something universal to all. The third part describes the general principles of the decision-making process for the effectiveness of PtDAs, and it also has commonality. 12 quality dimensions for the evaluation of the quality of PtDA, included: system development process, option information, probability of presentation,value of clarification and expression, patient story,guideing / coaching, disclosure of interests conflicts,providing decision support on the internet, balancing options, using clear language, information based on scientific evidence and establishing validity [15]. In the 12 quality dimensions, the quality dimension of the“patient story” does not reach the median threshold,because the potential benefits and disadvantages of the patient story for decision support are not clear, and therefore only serve as additional evaluation criteria[19-20].

It should be recognized that the IPDAS list has some deficiencies, mainly due to the inability to quantify PtDA [21]. The method of assessing quality has not objectively describe the total number of items in the list. It also fails to specify whether each item meets standard [22]. In response to these problems, a new quantitative evaluation tool (IPDASi) emerged. It was used to quantify the internal reliability of decision tool quality and quickly evolved from version 1.0 to 3.0.IPDASi (v3.0) includes 10 quality dimensions, 47 items, and reliability [21]. Evaluators scored each item,with strongly disagree (1 point), disagree (2 points),agree (3 points), and strongly agree (4 points) in four grades, reflecting the PtDA compliance to be evaluated.At the same time, the standards and criteria for the satisfaction of each item are also specified. For example, “agree” means that you think the tool meets this standard but there is still room for improvement(see Table 1 for the evolution of the IPDAS standard).

In order to establish the simplest evaluation standard for decision tools, in 2013, the Federation re-examined the IPDASi (v3.0), which improved and developed a new version of the certification tool IPDASI v4.0.These criteria can be used to “certify” PtDA as one of the major interventions for providing high quality healthcare and reducing the risk of patient decision-making. IPDASi (v4.0) contains 44 items in 3 categories, including 6 qualification standards, 10 certification standards and 28 quality standards [22].By analyzing the 30 decision aids, a total of 16 eligibility criteria and certification standards are considered as the minimum standards for evaluating PtDA, including screening decisions, diagnostic decisions, and clinical face-to-face consultations. The standard can be appropriately reduced [22].

In addition, based on the three category entries, the Federation made the following recommendations:eligibility criteria (6 entries) are the criteria that must be met to define a decision tool; if not achieved certification criteria (10 entries for screening decisions,for treatment decisions 6 items), it will result in a detrimental bias risk for PtDA; quality standards (28 items) can improve the quality of PtDA, but the absence of items does not lead to harmful risk of bias[22]. The current version 4.0 refines the evaluation criteria. The disadvantage is that it cannot evaluate the scientific of clinical medicine content, so it must be combined with the evaluation of the quality of evidence [23]. [For comparison of IPDASi (v3.0) and IPDASi (v4.0), see Table 2]

Feasibility and application of the simplest standard of international PtDA

Feasibility of the simplest standard of international PtDA

Studies have shown that IPDA is suitable for quality evaluation of most decision tools [24]. In 2015,Durand et al. used IPDASi (v3.0) to evaluate 30 decision-making tools included in the 2009 Cochrane Review, and the cochrane evaluation was chosen to ensure the diversity of the tools included, including different clinical backgrounds, developmental processes, and clinical interventions, these interventions comply with the inclusion criteria of the review. The final result showed that 25 (83.3%) of the decision-making tools met the eligibility criteria but only 3 (10%) met the certification standards and none of the decision tools that did not meet the eligibility criteria met the certification criteria [25]. Therefore,the eligibility criteria was treated as “gatekeeper”,suggesting that the quality of PtDA to be improved.Most patient decision-making tools to apply the current minimum standard is feasible [25]. In 2017, Lewis et al. used the revised IPDASi (v4.0) to describe and critically report the quality of 18 patient decision tools that were conducted in randomized controlled trials between June 2012 and April 2015 [26]. The 32 entries met all eligibility criteria and 2 (11.8%) met all certification criteria. The above studies demonstrate that the minimum certification standard for the IPDASi of the revised IPDASi (v4.0) include all of the eligibility criteria, 6 entries in the certification standards, and 10 entries in the quality standard. The results showed that of the 16 decision tools, 10 (58.8%)(v4.0) 16 entry is applicable to the certification and quality assessment of most of the PtDAs.

Table 1 Evolution of quality evaluation tools for PtDA

Table 2 The comparison of IPDASi (v3.0) and IPDASi (v4.0)

Application of the simplest Standard of International PtDA

With the development of shared decision-making,IPDAS has received more and more attention from researchers and patients as a criterion for evaluating PtDA [27]. It has been widely used to guide the development of PtDA. The IPDAS standard developed by the Ottawa University Research Center and has been adopted by the Clinical Decision and Communication Department of the John M [28].Eisenberg Center at Baylor College of Medicine in the United States. The adopted standard retains only the entries in the original entry that are important 9 points(ie., the reviewer’s full approval) containing a total of 31 entries to assess the quality of the tools included in the Ottawa AZ Decision Tools Database. In 2013,Berger et al. use the IPDAS standard to evaluate PtDA for care choices during pregnancy. They found that existing tools for decision-making were of low quality and raised the pressing need to develop high-quality evidence-based PtDA [29]. In the same year, Schoorel et al. developed a revised version of IPDAS based on the IPDAS checklist, containing 50 entries as a guideline for development and quality evaluation [30].The team developed a PtDA for re-delivery options after cesarean delivery that met 39 of the 50 IPDAS revisions (78%), including all (23 / 23) standards that meet the quality of “content” and most (16 / 20)criteria of the “development” quality. In 2015, Danish Rydahl et al. revised the IPDAS checklist and used this checklist to evaluate the decision-making manual for labor induction in all hospitals in Denmark before June 2015. The study found that the manual has low scores,poor quality, and lack of evaluation of the decision-making process [31]. In addition, the IPDAS standard is also widely used in the development and evaluation of PtDAs for cancer, respiratory diseases,cardiovascular diseases, childhood diseases [32-37]and others.

Problems in International IPDAS

Although various studies have proved the feasibility of IPDAS, and have been widely used in European and American countries, there are still some problems.There are differences in the individual, geographic, and cultural backgrounds of the patients, and IPDAS fails to summarize the possible differences. During the evaluation process, IPDAS may reduce the difference in decision-making services, but it is not enough to ensure the quality [38]. Therefore, developers of PtDA should select applicable items in the IPDAS standard in order to evaluate the PtDA more accurately and efficiently. In practical applications, many researchers also amended IPDAS entries based on research objectives [28, 30, 31]. Mcdonald pointed out that there are some concepts in IPDA that have unclear definitions, insufficient evidence, and even conflicting issues [39]. For example, in the presentation probability section, individual differences cannot be considered. As another example, using individual stories as an additional evaluation criterion, there is no sufficient evidence that this will increase the effectiveness of decision-making interventions [40]. In the process of development, evaluation and application of decision, it requires the input of manpower, material resources and financial resources. But the IPDAS standard fails to consider the decision-making economics [41].

Discussion and prospect

Improve decision quality

With the development of shared decision-making, as an important part, PtDAs have received more and more attention, although many problems are faced in the promotion and use [42-44]. Research demonstrates the role of PtDAs in improving the quality of clinical decision-making. First, the PtDA provides patients with relevant disease information and treatment options. The ability to participate in decision-making is enhanced by understanding the severity of the disease,the development and changes, the advantages of the various treatment options, and the risks involved.Second, PtDA helps patients achieve unity of value and choice. Patients can make unified decisions between doctors and patients based on their own values and preferences. Finally, PtDA requires both doctors and patients to participate in decision-making, improves patient care satisfaction, and improves patient compliance. At the same time, medical risks due to uncertainty are reduced. PtDA is an easy and effective way to integrate best evidence, doctor experience, and patient value.

Quality Evaluation of Medical Information

Medical health information is obtained from a wide range of sources, such as doctors, health brochures,television, medical journals, and the internet, among which the Internet is a very important method [45].The explosion of network information has made it faster and easier for people to obtain medical information from the Internet. In the complicated and miscellaneous health information, how to identify the authenticity of information, prevent injuries, and protect oneself are particularly important. In assessing the scientific nature of medical information, some researchers have explored it. In 1999, Charnock and others developed a tool named “DISCERN” to evaluate the quality of textual health information. The development of DISCERN promoted the pursuit of popular science medicine for the latest high-quality,evidence-based health information [46]. In 2002, the European Union established quality standards for network health information including six items [45].The Grading of Recommendations Assessment,Development and Evaluation (GRADE) is a milestone in the history of evidence development. It is strongly recommended that the GRADE system be used to evaluate the quality of clinical research evidence when developing PtDA. As an important carrier of information, the Internet is filled with a large number of unproven medical information. In clinical decision-making, patients need high-quality information based on scientific evidence [47]. IPDAS checklists and tools do not have the ability to assess the scientific of decision-making information and should be used in conjunction with various health information assessment standards to evaluate PtDA in many aspects such as scientificity, design, clinical validation, and reporting specifications.

Formulate PtDA and evaluation criteria that are in line with China's clinical practice

IPDAS is suitable for the quality evaluation and development guidance of most decision tools. Even if there are still some limitations, IPDAS still has high guiding value for PtDA developers, users, appraisers,and public health system stakeholders. In China’s medical environment, doctors work under pressure and suffer from a large number of patients. The average visit time per patient is very short. Using PtDA will inevitably require extra energy and time. The decision-making basis provided in PtDA generally comes from the results of group clinical trials.Therefore, it is necessary for clinicians to make adjustments according to individual conditions. This also requires experience skills and time commitment.In China, the concept of shared decision-making was first proposed at the 24th Great Wall International Congress of Cardiology in 2013. Due to cultural factors and shortage of medical resources, the current development is slow. Today, 15 years have passed since the establishment of the International Association for Decision Support Tools Quality Standards, we have reviewed and analyzed the development history and application status of IPDA. By drawing lessons,combining them with the characteristics of domestic medical care, it is helpful to develop PtDA and quality standards suitable for China’s local clinical environment, which also can avoid risks and promote shared decision-making economically and effectively.

1. Yu XP, Tong JY, Yu SH. Research on correlation between integrated management of biological psychosocial medicine model and maternal satisfaction. Tradit Med J 2009, 17, 645-646.

2. Chen DF. Focus on the sickness. Chin Health Service Manage 2005, 21, 720-721.

3. William G. Shared decision-making. M Healthcare quarterly 2009, 12: e186.

4. Mou W. The transformation strategy of TCM clinical evidence -- the development of decision aid tool. World J Med 2017, 06: 1261-1267.

5. Stacey D, Legare F, Lewis,K. et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017, 1:431.

6. Patient Decision Aids. Alphabetical List of Decision Aids by Health Topic, 2015.

7. Providing high quality, affordable health care to Washingtonians based on the recommendations of the blue ribbon commission on health care costs and access, SB 5930, Washington State, 2007.

8. Van W, Drenthen H. Shared decision making in the netherlands, is the time ripe for nationwide,structural implementation? Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2011, 2: 283-288.

9. Perestelo-P, Rivero S, Perez R, et al. Shared decision making in Spain: current state and future perspectives. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2011, 1: 289-295.

10. Lee BT, Chen C, Yu JH, et al. Computer-based learning module increases shared decision making in breast reconstructions. Ann Surg Onco1 2010,17: 738-743.

11. Liao ZF, Fang HP, Liu HJ. Current status and progress of patient decision support research. J Nursing Res 2014, 28: 4360-4363.

12. International Patient Decision Aid Standards,2011.

13. Lassman F, Henderson RC, Dockery L, et al.How does a decision aid help people decide whether to disclose a mental health problem to employers? Occup Rehabil 2015, 25: 403-411.

14. O'Connor AM, Stacey D, Entwistle V, et al.Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Systematic Reviews 2003, 13: D1431.

15. Elwyn G, Connor A, Stacey D, et al. Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. British Med J 2006, 333: 417.

16. Campbell SM, Cantrill JA, Roberts D. Prescribing indicators for UK general practice: consultation study. BMJ 2000, 321: 425-428.

17. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995,311: 376-380.

18. Mays N, Pope C,Jones J, Hunter D. Using the delphi and nominal group technique in health services research. Qualitative research in health care. London: BMJ Books, 1999.

19. Volk, RJ. Ten years of the international patient decision aid standards collaboration: evolution of the core dimensions for assessing the quality of patient decision aids. BMC Med Informatics &Decision Making 2013. 13: S1.

20. Bekker, HL, et al. Do personal stories make patient decision aids more effective? A critical review of theory and evidence. BMC Med Informatics & Decision Making 2013, 13: 1-9.

21. Elwyn G, O'Connor AM, Bennett C, et al.Assessing the quality of decision support technologies using the international patient decision aid standards instrument (IPDASi). Plos One 2009, 4: e4705.

22. Joseph N. Toward minimum standards for certifying patient decision aids: a modified delphi consensus process. Med Decision Making International J Society Med Decision Making,2013, 34: 699.

23. Elwyn, G. Many miles to go a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med 2013, 13: S14.

24. Holmes M. International patient decision aid standards (IPDAS): beyond decision aids to usual design of patient education materials. Health Expectations 2007, 10: 103-107.

25. Durand M. Minimum standards for the certification of patient decision support interventions: feasibility and application. Patient Education & Counseling 2015, 98: 462-468.

26. Lewis KB, et al. Quality of reporting of patient decision aids in recent randomized controlled trials: a descriptive synthesis and comparative analysis. Patient Education Counseling 2017, 1:1387-1393.

27. Connor AM, Wennberg J, Legare F, et al. Towards the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Affairs 2015, 26: 716-725.

28. Knowing Your Options: A Decision Aid for Men With Clinically Localized Prostate Cancer.Available. Med 2016, 1: 20-35.

29. Berger B, Schwarz C, Heusser P. Watchful waiting or induction of labour-a matter of informed choice: identification, analysis and critical appraisal of decision aids and patient information regarding care options for women with uncomplicated singleton late and post term pregnancies: a review. BMC Complement Altern Med 2015, 1: 143.

30. Schoorel EN. Vankan E. Scheepers HC, et al.Involving women in personalised decision-making on mode of delivery after caesarean section: the development and pilot testing of a patient decision aid. BJOG 2014, 121:202-209.

31. Clausen JA, Juhl M, Rydahl, E. Quality assessment of patient leaflets on misoprostol-induced labour: does written information adhere to international standards for patient involvement and informed consent? BMJ Open 2016, 6: 5.

32. Hawley ST. Evaluating a decision aid for improving decision making in patients with early-stage breast cancer. Patient-patient Centered Outcomes Res 2016, 1: 161-169.

33. Williams L, Jones W, Elwyn G, et al. Interactive patient decision aids for women facing genetic testing for familial breast cancer: a systematic web and literature review. J Eval Clin Pract 2008,70: 4.

34. Trenaman L, Munro S, Almeida F. Development of a patient decision aid prototype for adults with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Breath 2016, 12:653-661.

35. Fraenkel L, Street RLJ, Fried J, et al.Development of a tool to improve the quality of decision making in atrial fibrillation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011, 11: 59.

36. Maguire E, Hong P, Ritchie K, et al. Decision aid prototype development for parents considering adenotonsillectomy for their children with sleep disordered breathing. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 22: 57.

37. Bekker HL. The loss of reason in patient decision aid research: do checklists damage the quality of informed choice interventions? Patient Education& Counseling 2010, 78: 357-364.

38. Mcdonald H, Charles C, Gafni A. Assessing the conceptual clarity and evidence base of quality criteria / standards developed for evaluating decision aids. Health Expectations Internat J Public Participation 2014, 17: 232-243.

39. Bekker HL, Winterbottom AE, Butow P, et al. Do personal stories make patient decision aids more effective? A critical review of theory and evidence.BMC Med 2013, 13: 1-9.

40. Blumenthal JS, Robinson E, Cantor SB. The neglected topic: presentation of cost information in patient decision aids. Med Decision Making Inter J 2015, 35: 412-418.

41. Légaré F, Stacey D, Forest PG. Moving SDM forward in Canada: milestones, public involvement, and barriers that remain. Z Evid Fortbild Qual 2011, 105: 245-253.

42. Rashidian H, Nedjat S, Majdzadeh R. The perspectives of iranian physicians and patients towards patient decision aids: a qualitative study.BMC Res Notes 2013, 34: 379.

43. O'Connor AM, Wennberg J, Legare F, et al.Towards the ‘tipping point’: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Affairs 2014, 26:716-725.

44. Brussels C. Communities CO. Europe 2002:quality criteria for health related websites. J Med Internet Res 2002, 4: E15.

45. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, et al. An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices.J Epidemiol Community Health 1999, 53:105-111.

46. CE Rees, JE Ford. Evaluating the reliability of a tool for assessing the quality of written patient information on treatment choices. Patient Education Counseling 2002, 47, 273-275.

47. Wang DF. Drug and therapeutics bulletin: an introduction to patient decision aids. BMJ 2013,347: 4147.

杂志排行

TMR Integrative Medicine的其它文章

- Necessities and feasibilities of the establishment of traditional Chinese medicine clinical research protocol database

- Patient decision aids for cardiovascular disease: the status-quo and prospects

- Network pharmacology: an important breakthrough in traditional Chinese medicine research

- The concept of narrative evidence-based medicine and shared decision-making in traditional Chinese medical practice